Astronomy:Exploration Systems Architecture Study

The Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS) is the official title of a large-scale, system level study released by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in November 2005 of his goal of returning astronauts to the Moon and eventually Mars—known as the Vision for Space Exploration (and unofficially as "Moon, Mars and Beyond" in some aerospace circles, though the specifics of a crewed "beyond" program remain vague). The Constellation Program was cancelled in 2010 by the Obama Administration and replaced with the Space Launch System, later renamed as the Artemis Program in 2017 under the Trump Administration.

Scope

NASA Administrator Michael Griffin ordered a number of changes in the originally planned Crew Exploration Vehicle (now Orion MPCV) acquisition strategy designed by his predecessor Sean O'Keefe. Griffin's plans favored a design he had developed as part of a study for the Planetary Society, rather than the prior plans for a Crew Exploration Vehicle developed in parallel by two competing teams. These changes were proposed in an internal study called the Exploration Systems Architecture Study,[1] whose results were officially presented during a press conference held at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., on September 19, 2005.

The ESAS included a number of recommendations for accelerating the development of the CEV and implementing Project Constellation, including strategies for flying crewed CEV flights as early as 2012 and methods for servicing the International Space Station (ISS) without the use of the Space Shuttle,[2] using cargo versions of the CEV.

Originally slated for release as early as July 25, 2005, after the "Return to Flight" mission of Discovery, the release of the ESAS was delayed until September 19, reportedly due to poor reviews of the presentation of the plan and some resistance from the Office of Management and Budget.[2]

Shuttle based launch system

The initial CEV “procurement strategies” under Sean O’ Keefe would have seen two “phases” of CEV design. Proposals submitted in May 2005 were to be part of the Phase 1 portion of CEV design, which was to be followed by an orbital or suborbital fly-off of technology demonstrator spacecraft called FAST in 2008. Downselect to one contractor for Phase 2 of the program would have occurred later that year. First crewed flight of the CEV would not occur until as late as 2014. In the original plan favored by former NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe, the CEV would launch on an Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV), namely the Boeing Delta IV Heavy or Lockheed Martin Atlas V Heavy EELVs.

However, with the change of NASA Administrators, Mike Griffin did away with this schedule, viewing it as unacceptably slow, and moved directly to Phase 2 in early 2006. He commissioned the 60-day internal study for a re-review of the concepts—now known as the ESAS—which favored launching the CEV on a shuttle-derived launch vehicle. Additionally, Griffin planned to accelerate or otherwise change a number of aspects of the original plan that was released last year[when?]. Instead of a CEV fly-off in 2008, NASA would have moved to Phase 2 of the CEV program in 2006, with CEV flights to have commenced as early as June 2011.[citation needed]

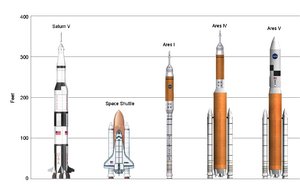

The ESAS called for the development of two shuttle-derived launch vehicles to support the now defunct Constellation Program;[3] one derived from the space shuttle's solid rocket booster which would become the now cancelled Ares I to launch the CEV, and an in-line heavy-lift vehicle using SRBs and the shuttle's external tank to launch the Earth Departure Stage and Lunar Surface Access Module which was known as Ares V (this design was reused for the Space Launch System). The performance of the Cargo Shuttle Derived Launch Vehicle (SDLV) would be 125 to 130 metric tons to Low Earth Orbit (LEO). A SDLV would allow a much greater payload per launch than an EELV option.

The crew would be launched in the CEV atop a five-segment derivative of the Shuttle's Solid Rocket Booster and a new liquid-propellant upper stage based on the Shuttle's External Tank. Originally to be powered by a single, throw-away version of the Space Shuttle Main Engine, it was later changed to a modernized and uprated version of the J-2 rocket engine (known as the J-2X) used on the S-IVB upper stages used on the Saturn IB and Saturn V rockets. This booster would be capable of placing up to 25 tons into low Earth orbit. The booster would use components that have already been man-rated.[citation needed]

Cargo would be launched on a heavy-lift version of the Space Shuttle, which would be an "in-line" booster that would mount payloads on top of the booster. The in-line option originally featured five throw-away versions of the SSMEs on the core stage, but was changed later to five RS-68 rocket engines (currently in use on the Delta IV Heavy rocket), with higher thrust and lower costs, which required a slight increase in the overall diameter of the core. Two enlarged five-segment SRBs would help the RS-68 engines propel the rocket's second stage, known as the Earth Departure Stage (EDS), and payload into LEO. It could lift about 125 tons to LEO, and was estimated to cost $540 million per launch.

The infrastructure at Kennedy Space Center, including the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) and Shuttle launch pads LC-39A and 39B was maintained and adapted to the needs of future giant launch vehicle. The new pad LC-39C was later constructed to support small launch vehicles with the option of constructing LC-39D or resurrecting the former LC-34 or LC-37A pads at the nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station used by the Saturn IB for the early Apollo earth orbital missions.[citation needed]

CEV configuration

The ESAS recommended strategies for flying the crewed CEV by 2014, and endorsed a Lunar Orbit Rendezvous approach to the Moon. The LEO versions of the CEV would carry crews four to six to the ISS. The lunar version of the CEV would carry a crew of four and the Mars CEV would carry six. Cargo could also be carried aboard an uncrewed version CEV, similar to the Russian Progress cargo ships. Lockheed Martin was selected as the contractor for the CEV by NASA. This vehicle would ultimately become the Orion MPCV with its first flight in 2014 (EFT-1), its first crewed flight in 2022 (Artemis 2), and first lunar landing flight in 2024 (Artemis 3). Only one version of the vehicle was constructed to support deep space missions with ISS crew transfers being handled by the Commercial Crew Program.

The CEV re-entry module would weigh about 12 tons—almost twice the mass of the Apollo Command Module—and, like Apollo, would be attached to a service module for life support and propulsion (European Service Module). The CEV would be an Apollo-like capsule, with a Viking-type heat shield, not a lifting body or winged vehicle like the Shuttle was. It would touch down on land rather than water, similar to the Russia n Soyuz spacecraft. This would be changed to splashdown only to save weight, the CST-100 Starliner would be the first US spacecraft to touchdown on land. Possible landing areas that had been identified included Edwards Air Force Base, California, Carson Flats (Carson Sink[4]), Nevada, and the area around Moses Lake, Washington state. Landing on the west coast would allow the majority of the reentry path to be flown over the Pacific Ocean rather than populated areas. The CEV would use an ablative (Apollo-like) heat shield that would be discarded after each use, and the CEV itself could be reused about 10 times.

Accelerated lunar mission development was slated to start by 2010, once the Shuttle retired. The Lunar Surface Access Module, which would later be known as Altair, and heavy-lift booster (Ares V) would be developed in parallel and would both be ready for flight by 2018. The eventual goal was to achieve a lunar landing by 2020, the Artemis Program is now targeting a lunar landing in 2024. The LSAM would be much larger than the Apollo Lunar Module and would be capable of carrying up to 23 tons of cargo to the lunar surface to support a lunar outpost.

Like the Apollo LM, the LSAM would include a descent stage for landing and an ascent stage for returning to orbit. The crew of four would ride in the ascent stage. The ascent stage would be powered by a methane/oxygen fuel for return to lunar orbit (later changed to liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, due to the infancy of oxygen/methane rocket propulsion). This would allow a derivative of the same lander to be used on later Mars missions, where methane propellant can be manufactured from the Martian soil in a process known as In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). The LSAM would support the crew of four on the lunar surface for about a week and use advanced roving vehicles to explore the lunar surface. The huge amount of cargo carried by the LSAM would be extremely beneficial for supporting a lunar base and for bringing large amounts of scientific equipment to the lunar surface. Artemis will use separately launched landers under the CLPS Program to deliver support equipment for lunar outposts.

Lunar mission profile

The lunar mission profile was a combination of earth orbit rendezvous and lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) approach. First, the LSAM and the EDS would be launched atop the heavy-lift, Shuttle-derived vehicle (Ares V). The EDS would be a derivative of the S-IVB upper stage used on the Saturn V rocket and will use a single J-2X engine similar to that used on the SRB-derived booster[citation needed] (originally two J-2X engines were to be used, but the RS-68 engines for the core stage will allow NASA to only use one). The crew would then be launched in the CEV on the SRB-derived booster (Ares I), and the CEV and LSAM will dock in Earth orbit. The EDS would then send the complex to the Moon. The LSAM would brake the complex into lunar orbit (similar to the Block D rocket on the failed Soviet moonshot attempt in the 1960s and 1970s), where four astronauts would board the LSAM for descent to the lunar surface for a week of exploration. Part of the LSAM could be left behind with cargo to begin the establishment of a long-term outpost.

Both the LSAM and the lunar CEV would carry a crew of four. The entire crew would descend to the lunar surface, leaving the CEV unoccupied.[5] After the time on the lunar surface had been spent, the crew would return to lunar orbit in the ascent stage of the LSAM. The LSAM would dock with the CEV. The crew would return to the CEV and jettison the LSAM, and then the CEV's engine would put the crew on a course for Earth. Then, much like Apollo, the service module would be jettisoned and the CEV would descend for a landing via a system of three parachutes.

Ultimately a NASA-sponsored lunar outpost would be built, possibly near the Moon's south pole. But this decision had not yet been taken and would depend on potential international and commercial participation in the exploration project. The Artemis Program hopes to set up a small international lunar outpost by 2028[citation needed]

Extension to Mars

The use of scalable CEVs and a lander with methane-fueled engines meant that meaningful hardware testing for Mars missions could be done on the Moon. The eventual Mars missions would start to be planned in detail around 2020 and would include the use of Lunar ISRU and also be "conjunction-class", meaning that rather than doing a Venus flyby and spending 20–40 days on the Martian surface, the crew would go directly to Mars and back and spend about 500–600 days exploring Mars.

Costs

The ESAS estimated the cost of the crewed lunar program through 2025 to be $217 billion, only $7 billion more than NASA's current projected exploration budget through that time.

The ESAS proposal was originally said to be achievable using only existing NASA funding, without significant cuts to NASA's other programs, however, it soon became apparent that much more money was needed. Supporters of Constellation saw this as a justification for terminating the Shuttle program as soon as possible, and NASA implemented a plan to terminate support for both Shuttle and ISS in 2010. This was about 10 years earlier than planned for both programs, so must be considered a significant cut. This resulted in strong objections from the international partners that the US was not meeting its commitments, and concerns in Congress that the investment in ISS would be wasted.

Criticism

Beginning April 2006 there were some criticisms on the feasibility of the original ESAS study. These mostly revolved around the use of methane-oxygen fuel. NASA originally sought this combination because it could be "mined" in situ from lunar or martian soil – something that could be potentially useful on missions to these celestial bodies. However, the technology is relatively new and untested. It would add significant time to the project and significant weight to the system. In July, 2006, NASA responded to these criticisms by changing the plan to traditional rocket fuels (liquid hydrogen and oxygen for the LSAM and hypergolics for the CEV). This has reduced the weight and shortened the project's timeframe.[6]

However, the primary criticism of the ESAS was based on its estimates of safety and cost. The authors used the launch failure rate of the Titan III and IV as an estimate for the failure rate of the Delta IV heavy. The Titan combined a core stage derived from an early ICBM with large segmented solid fuel boosters and a hydrogen-fueled upper stage developed earlier. It was a complex vehicle and had a relatively high failure rate. In contrast, the Delta IV Heavy was a "clean sheet" design, still in service, which used only liquid propellant. Conversely, the failure rate of the Shuttle SRB was used to estimate the failure rate of the Ares I, however only launches subsequent to the loss of Challenger were considered, and each shuttle launch was considered to be two successful launches of the Ares even though the Shuttle SRBs do not include systems for guidance or roll control.

The Delta IV is currently launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Complex 37, and the manufacturer, United Launch Alliance, had proposed launching human flights from there. However, in the estimation of costs, the ESAS assumed that all competing designs would have to be launched from Launch Complex 39, and that the Vehicle Assembly Building, Mobile launcher Platforms and pads A and B would have to be modified to accommodate them. The LC-39 facilities are much larger, more complex, older, and more expensive to maintain than the modern facilities at Complex 37 and are entirely inappropriate for the Delta, which is integrated horizontally and transported unfueled. This assumption was not justified in the report and greatly increased the estimated operational cost for the Delta IV. Finally, the decision in 2011 to add an uncrewed test of the Orion on a Delta IV clearly contradicts the ESAS conclusion that this was infeasible.

Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee

The Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee (also known as the HSF Committee, Augustine Commission, or Augustine Committee) was a group convened by NASA at the request of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), to review the nation's human spaceflight plans to ensure "a vigorous and sustainable path to achieving its boldest aspirations in space." The review was announced by the OSTP on May 7, 2009. It covered human spaceflight options after the time NASA had planned to retire the Space Shuttle. A summary report was provided to the OSTP Director John Holdren, White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), and NASA Administrator on September 8, 2009. The estimated cost associated with the review was expected to be US$3 million. The committee was scheduled to be active for 180 days; the report was released on October 22, 2009.

The Committee judged the 9-year old Constellation program to be so behind schedule, underfunded and over budget that meeting any of its goals would not be possible. President Obama removed the program from the 2010 budget effectively canceling the program. One component of the program, the Orion crew capsule was added back to plans but as a rescue vehicle to complement the Russian Soyuz in returning Station crews to Earth in the event of an emergency.

The proposed "ultimate goal" for human space flight would appear to require two basic objectives: (1) physical sustainability and (2) economic sustainability. The Committee adds a third objective: to meet key national objectives. These might include international cooperation, developing new industries, energy independence, reducing climate change, national prestige, etc. Therefore, the ideal destination should contain resources such as water to sustain life (also providing oxygen for breathing, and hydrogen to combine with oxygen for rocket fuel), and precious and industrial metals and other resources that may be of value for space construction and perhaps in some cases worth returning to Earth (e.g., see asteroid mining).

See also

- Crew Exploration Vehicle

- Crew Space Transportation System

- Liquid Rocket Booster

- Reusable launch system

- Shuttle-derived vehicle

- Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster

References

- ↑ "Crew Exploration Vehicle Procurement". NASA. http://exploration.nasa.gov/acquisition/cev_procurement3_lite.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "NASA Studying Unmanned Solution to Complete Space Station as Return to Flight Costs Grow". spaceref.com. 24 July 2005. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewnews.html?id=1052.

- ↑ "NASA Plans to Build Two New Shuttle-derived Launch Vehicles". spaceref.com. July 2005. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewnews.html?id=1040.

- ↑ "Surface Landing Site Weather Analysis for NASA's Constellation Program". https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20080013577_2008013473.pdf.

- ↑ "Remarks for AIAA Space 2005 Conference & Exhibition". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/126521main_MDG_AIAA_Space_2005.pdf.

- ↑ "NASA makes major design changes to CEV". nasaspaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/content/?cid=4659.

External links

- NASA's Exploration Systems Architecture Study

- Official Constellation NASA Web Site

- Official Orion NASA Web Site

- Official Ares NASA Web Site

- White House: A Renewed Spirit of Discovery

- President's Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy

- NASA: Exploration Systems

- Apollo 2.0: Moon Program on Drugs

- National Space Society

- NASA formally unveils lunar exploration architecture

- NASA Revives Apollo - While Starving Space Life Science

- Full Resolution Photos of NASA's New Spaceship

- ESAS Fact sheet

- ESAS Presentation

- Full ESAS report

- ESAS Appendix with launch vehicle configurations

- QuickTime animation

- Spacedaily on ESAS

|