Astronomy:Spaceplane

A spaceplane is a vehicle that can fly and glide as an aircraft in Earth's atmosphere and function as a spacecraft in outer space.[1] To do so, spaceplanes must incorporate features of both aircraft and spacecraft. Orbital spaceplanes tend to be more similar to conventional spacecraft, while sub-orbital spaceplanes tend to be more similar to fixed-wing aircraft. All spaceplanes as of 2024 have been rocket-powered for takeoff and climb, but have then landed as unpowered gliders.

Four examples of spaceplanes have successfully launched to orbit, reentered Earth's atmosphere, and landed: the U.S. Space Shuttle, the Russian Buran, the U.S. X-37,[2] and the Chinese Shenlong. Another, Dream Chaser, is under development in the U.S. As of 2024, all past and current orbital spaceplanes launch vertically; some are carried as a payload in a conventional fairing, while the Space Shuttle used its own engines with the assistance of boosters and an external tank. Orbital spaceflight takes place at high velocities, with orbital kinetic energies typically greater than suborbital trajectories. This kinetic energy is shed as heat during re-entry. Many more spaceplanes have been proposed.

At least two suborbital rocket-powered aircraft have been launched horizontally into sub-orbital spaceflight from an airborne carrier aircraft before rocketing beyond the Kármán line: the X-15 and SpaceShipOne.[lower-alpha 1]

Principles of operation

Spaceplanes must operate in space, like traditional spacecraft, but also must be capable of atmospheric flight, like an aircraft.

Spaceplanes do not necessarily have to fly by their own propulsion, but instead often glide with their inertia while using aerodynamic surfaces to maneuver in the atmosphere during descent and landing. The U.S. Space Shuttle for instance, could not fly under its own propulsion but used its momentum after de-orbit to glide to the runway destination.[3][4][5]

These requirements drive up the complexity, risk, dry mass, and cost of spaceplane designs. The following sections will draw heavily on the US Space Shuttle as the biggest, most complex, most expensive, most flown, and only crewed orbital spaceplane, but other designs have been successfully flown.

Launch to space

The flight trajectory required to reach orbit results in significant aerodynamic loads, vibrations, and accelerations, all of which have to be withstood by the vehicle structure.[6][7][8]

If the launch vehicle suffers a catastrophic malfunction, a conventional capsule spacecraft is propelled to safety by a launch escape system. The Space Shuttle was far too big and heavy for this approach to be viable, resulting in a number of abort modes that may or may not have been survivable. The Challenger disaster demonstrated a lack of survivability on ascent.[citation needed]

Space environment

Once on-orbit, a spaceplane must be supplied with power by solar panels and batteries or fuel cells, maneuvered in space, kept in thermal equilibrium, oriented, and communicated with. On-orbit thermal and radiological environments impose additional stresses. This is in addition to accomplishing the task the spaceplane was launched to complete, such as satellite deployment or science experiments.[citation needed]

The Space Shuttle used dedicated engines to accomplish orbital maneuvers. These engines used toxic hypergolic propellants that required special handling precautions. Various gases, including helium for pressurization and nitrogen for life support, were stored under high pressure in composite overwrapped pressure vessels.[citation needed]

Atmospheric reentry

Orbital spacecraft reentering the Earth's atmosphere must shed significant velocity, resulting in extreme heating. For example, the Space Shuttle thermal protection system (TPS) protects the orbiter's interior structure from surface temperatures that reach as high as 1,650 °C (3,000 °F), well above the melting point of steel.[9] Suborbital spaceplanes fly lower energy trajectories that do not put as much stress on the spacecraft thermal protection system.

The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster was the direct result of a TPS failure.

Aerodynamic flight and horizontal landing

Aerodynamic control surfaces must be actuated. Landing gear must be included at the cost of additional mass.

Air-breathing orbital spaceplane concept

An air-breathing orbital spaceplane would have to fly what is known as a 'depressed trajectory,' which places the vehicle in the high-altitude hypersonic flight regime of the atmosphere for an extended period of time. This environment induces high dynamic pressure, high temperature, and high heat flow loads particularly upon the leading edge surfaces of the spaceplane, requiring exterior surfaces to be constructed from advanced materials and/or use active cooling.[8] Skylon was a proposed spaceplane that would have used air-breathing engines.

Flown orbital spaceplanes

Space Shuttle

Buran

X-37

Reusable experimental spacecraft

Flown suborbital rocket planes

United States

Two piloted suborbital rocket-powered aircraft have reached space: the North American X-15 and SpaceShipOne; a third, SpaceShipTwo, has crossed the US-defined boundary of space but has not reached the higher internationally recognised boundary. None of these crafts were capable of entering orbit, and all were first lifted to high altitude by a carrier aircraft.

On 7 December 2009, Scaled Composites and Virgin Galactic unveiled SpaceShipTwo, along with its atmospheric mothership "Eve". On 13 December 2018, SpaceShipTwo VSS Unity successfully crossed the US-defined boundary of space (although it has not reached space using the internationally recognised definition of this boundary, which lies at a higher altitude than the US boundary). SpaceShipThree is the new spacecraft of Virgin Galactic, launched on 30 March 2021. It is also known as VSS Imagine.[10] On 11 July 2021 VSS Unity completed its first fully crewed mission including Sir Richard Branson.

Soviet Union

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-105 was an atmospheric prototype of an intended orbital spaceplane, with the suborbital BOR-4 subscale heat shield test vehicle successfully reentering the atmosphere before program cancellation.

Japan

HYFLEX was a miniaturized suborbital demonstrator launched in 1996, flying to 110 km altitude, achieving hypersonic flight, and successfully reentering the atmosphere.[11][12]

Europe

The European Space Agency (ESA) test project Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle (IXV) has demonstrated lifting body reentry technologies during a 100-minute suborbital flight in 2015.

Other

The Dawn Mk-II Aurora is a suborbital spaceplane being developed by Dawn Aerospace to demonstrate multiple suborbital flights per day. Dawn is based in the Netherlands and New Zealand, and is working closely with the American CAA. On 9 December 2020, the Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand, working alongside the New Zealand Space Agency, issued a license allowing the vehicle to fly from a conventional airport.[13] Early flight testing began with surrogate jet engines, and in July 2021 the company completed a series of five test flights assessing the airframe, avionics and rapid-turnaround operations. Dawn Aerospace[14]

Aurora has since undergone extensive flight testing, including dozens of jet-engine flights and subsequent certification for rocket-powered and supersonic flight. In November 2024, the Mk-II Aurora became the first aircraft designed and manufactured in New Zealand to break the sound barrier, reaching Mach 1.12 and setting a record for the fastest climb to 20 km altitude.[15]

In 2025, Dawn Aerospace began flying commercial and research payloads on Aurora, including space domain awareness sensors and university research instruments, demonstrating the vehicle’s potential for reusable suborbital services. [16]

The company has also started taking orders for the Aurora, with first deliveries expected in 2027, and signed partnerships to base an Aurora spaceplane at the Oklahoma Air & Space Port in the United States. [17]

Spaceplanes in development

China

Shenlong (Chinese: 神龙; pinyin: shén lóng; literally: 'divine dragon') is a Chinese robotic spaceplane that may be similar to the Boeing X-37.[18] Only a few images have been released since late 2007.[19][20][21]

Haolong is a reusable uncrewed spaceplane with a 1.8 ton cargo capacity in development by the Chengdu Aircraft Design and Research Institute for resupplying the Tiangong space station. It will be 10 meters long and 8 meters wide and will use folding wings.[22]

Europe

The experience from the IXV project is being used in the PRIDE programme to develop the uncrewed reusable spaceplane Space Rider.[23]

The German Space Agency (DLR) is developing the Reusable Flight Experiment (ReFEx) as a demonstrator for a winged reusable rocket first stage. It will be carried by a sounding rocket to apogee of approximately 130 km.[24] Its first flight is expected in 2026.[25]

The German company POLARIS Spaceplanes, in cooperation with DLR, is developing a multipurpose suborbital spaceplane Aurora that can be used for launching payloads into orbit when combined with an expendable upper stage.[26][27][28][29]

Dassault Aviation and OHB[30] are developing an orbital spaceplane called VORTEX (Véhicule Orbital Réutilisable de Transport et d’EXploration) for both civilian and military orbital missions. The company first presented this project at the 2025 Paris Air Show.[31][32] ESA expressed an interest to cooperate on a scaled down suborbital technology demonstrator version of VORTEX.[33]

French company AndroMach, founded in 2023, is developing small suborbital (ENVOL) and orbital (ÉTOILE) spaceplanes with financial support by CNES.[34][29]

INVICTUS will be a hypersonic flight test vehicle, enabling technologies for future reusable spaceplanes.[35]

India

As of 2012[update], the Indian Space Research Organisation is developing a launch system named the Reusable Launch Vehicle (RLV). It is India's first step towards realizing a two-stage-to-orbit reusable launch system. A space plane serves as the second stage. The plane is expected to have air-breathing scramjet engines as well as rocket engines. Tests with miniature spaceplanes and a working scramjet have been conducted by ISRO in 2016.[36] In April 2023, India successfully conducted an autonomous landing mission of a scaled-down prototype of the spaceplane.[37] The RLV prototype was dropped from a Chinook helicopter at an altitude of 4.5 km and was made to autonomously glide down to a purpose-built runway at the Chitradurga Aeronautical Test Range, Karnataka.[38]

Japan

As of 2018, Japan is developing the Winged Reusable Sounding rocket (WIRES), which if successful, may be used as a recoverable first-stage or as a crewed sub-orbital spaceplane.[39]

United States

Unflown spaceplane concepts

Various types of spaceplanes have been suggested since the early twentieth century. Notable early designs include a spaceplane equipped with wings made of combustible alloys that it would burn during its ascent, and the Silbervogel bomber concept. World War II Germany and the postwar US considered winged versions of the V-2 rocket, and in the 1950s and '60s winged rocket designs inspired science fiction artists, filmmakers, and the general public.[40][41]

United States

The U.S. Air Force invested some effort in a paper study of a variety of spaceplane projects under their Aerospaceplane efforts of the late 1950s, but later reduced the scope of the project. The result, the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar, was to have been the first orbital spaceplane, but was canceled in the early 1960s[42][43] in lieu of NASA's Project Gemini and the U.S. Air Force's crewed spaceflight program. In 1961, NASA originally planned to have the Gemini spacecraft land on a runway[44] with a Rogallo wing airfoil, rather than an ocean landing under parachutes. The test vehicle became known as the Paraglider Research Vehicle. Development work on both parachutes and the paraglider began in 1963.[45] By December 1963, the parachute was ready to undergo full-scale deployment testing, while the paraglider had run into technical difficulties.[45] Though attempts to revive the paraglider concept persisted within NASA and North American Aviation, in 1964 development was definitively discontinued due to the expense of overcoming the technical hurdles.[46]

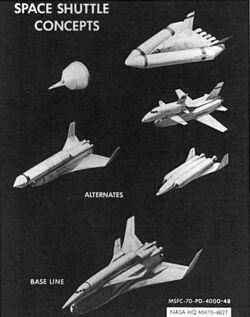

The Space Shuttle underwent many variations during its conceptual design phase. Some early concepts are illustrated.

The Rockwell X-30 National Aero-Space Plane (NASP), begun in the 1980s, was an attempt to build a scramjet vehicle capable of operating like an aircraft and achieving orbit like the shuttle. Introduced to the public in 1986, the concept was intended to reach Mach 25, enabling flights between Dulles Airport to Tokyo in two hours, while also being capable of low Earth orbit.[47] Six critical technologies were identified, three relating to the propulsion system, which would consist of a hydrogen-fueled scramjet.[47]

The NASP program became the Hypersonic Systems Technology Program (HySTP) in late 1994. HySTP was designed to transfer the accomplishments made in hypersonic flight into a technology development program. On 27 January 1995 the Air Force terminated participation in (HySTP).[47]

In 1994, a USAF captain proposed an F-16 sized single-stage-to-orbit peroxide/kerosene spaceplane called "Black Horse".[48] It was to take off almost empty and undergo aerial refueling before rocketing to orbit.[49]

On 5 March 2006, Aviation Week & Space Technology published a story purporting to be the "outing" of a highly classified U.S. military two-stage-to-orbit spaceplane system with the code name Blackstar.[50]

In 2011, Boeing proposed the X-37C, a 165 to 180 percent scale X-37B built to carry up to six passengers to low Earth orbit. The spaceplane was also intended to carry cargo, with both upmass and downmass capacity.[51]

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union first considered a preliminary design of rocket-launch small spaceplane Lapotok in early 1960s. The Spiral airspace system with small orbital spaceplane and rocket as second stage was developed in the 1960s–1980s. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-105 was a crewed test vehicle to explore low-speed handling and landing.[52]

Russia

In the early 2000s the orbital 'cosmoplane' (Russian: космоплан) was proposed by Russia's Institute of Applied Mechanics as a passenger transport. According to researchers, it could take about 20 minutes to fly from Moscow to Paris, using hydrogen and oxygen-fueled engines.[53][54]

Europe

The Multi-Unit Space Transport And Recovery Device (MUSTARD) was a concept explored by the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) around 1968 for launching payloads weighing as much as 2,300 kg (5,000 lb) into orbit. It was never constructed.[55]

In the 1980s, British Aerospace began development of HOTOL, an SSTO spaceplane powered by a revolutionary SABRE air-breathing rocket engine, but the project was canceled due to technical and financial uncertainties.[56] The inventor of SABRE set up Reaction Engines to develop SABRE and proposed a twin-engined SSTO spaceplane called Skylon.[57] One NASA analysis showed possible issues with the hot rocket exhaust plumes causing heating of the tail structure at high Mach numbers.[58] although the CEO of Skylon Enterprises Ltd has claimed that reviews by NASA were "quite positive".[59]

Bristol Spaceplanes has undertaken design and prototyping of three potential spaceplanes since its founding by David Ashford in 1991. The European Space Agency has endorsed these designs on several occasions.[60]

France worked on the Hermes crewed spaceplane launched by Ariane rocket in the late 20th century, and proposed in January 1985 to go through with Hermes development under the auspices of the ESA.[61]

In the 1980s, West Germany funded design work on the MBB Sänger II with the Hypersonic Technology Program. Development continued on MBB/Deutsche Aerospace Sänger II/HORUS until the late 1980s when it was canceled. Germany went on to participate in the Ariane rocket, Columbus space station and Hermes spaceplane of ESA, Spacelab of ESA-NASA and Deutschland missions (non-U.S. funded Space Shuttle flights with Spacelab). The Sänger II had predicted cost savings of up to 30 percent over expendable rockets.[62][63]

Hopper was one of several proposals for a European reusable launch vehicle (RLV) planned to cheaply ferry satellites into orbit by 2015.[64] One of those was 'Phoenix', a German project which is a one-seventh scale model of the Hopper concept vehicle.[65] The suborbital Hopper was a Future European Space Transportation Investigations Programme system study design[66] A test project, the Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle (IXV), has demonstrated lifting reentry technologies and will be extended under the PRIDE programme.[23]

The FAST20XX Future High-Altitude High Speed Transport 20XX aimed to establish sound technological foundations for the introduction of advanced concepts in suborbital high-speed transportation with air-launch-to-orbit ALPHA vehicle.[67]

Airbus Defence and Space Spaceplane was a suborbital spaceplane concept for carrying space tourists, proposed by EADS Astrium in 2007.[68]

Japan

India

AVATAR (Aerobic Vehicle for Hypersonic Aerospace Transportation; Sanskrit: अवतार) was a concept study for an uncrewed single-stage reusable spaceplane capable of horizontal takeoff and landing, presented to India's Defence Research and Development Organisation. The mission concept was for low cost military and commercial satellite launches.[69][70][71]

See also

- Ansari X Prize

- List of crewed spacecraft

- List of space launch system designs

Notes

- ↑ In 2018, SpaceShipTwo passed the US definition of space of 80km, but not the 100km Kármán line.

References

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (20 October 2014). "25 Years Ago, NASA Envisioned Its Own 'Orient Express'". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/21/science/25-years-ago-nasa-envisioned-its-own-orient-express.html.

- ↑ Piesing, Mark (22 January 2021). "Spaceplanes: The return of the reusable spacecraft?". https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210121-spaceplanes-the-return-of-the-reuseable-spacecraft.

- ↑ "Re-entry and Landing Procedures: A Guide to Safe Spacecraft Descent - Space Voyage Ventures" (in en-GB). 2024-02-23. https://spacevoyageventures.com/re-entry-and-landing-procedures/.

- ↑ "The Aeronautics of the Space Shuttle - NASA" (in en-US). 2003-12-29. https://www.nasa.gov/centers-and-facilities/langley/the-aeronautics-of-the-space-shuttle/.

- ↑ "Returning from Space: Re-entry". https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/III.4.1.7_Returning_from_Space.pdf.

- ↑ "Aerodynamics and Debris Transport for the Space Shuttle Launch Vehicle". https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20120014272/downloads/20120014272.pdf.

- ↑ "UNSTEADY AERODYNAMIC ANALYSIS OF SPACE SHUTTLE VEHICLES". August 1973. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19730024030/downloads/19730024030.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "X-15 Hypersonic Research Program - NASA" (in en-US). https://www.nasa.gov/reference/x-15/.

- ↑ "Orbiter Thermal Protection System". NASA/Kennedy Space Center. 1989. http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/nasafact/tps.htm.

- ↑ Grush, Lauren (13 December 2018). "Virgin Galactic's spaceplane finally makes it to space for the first time". https://www.theverge.com/2018/12/13/18138279/virgin-galactic-vss-unity-spaceshiptwo-space-tourism.

- ↑ "Hyflex". http://www.astronautix.com/craft/hyflex.htm.

- ↑ "HYFLEX". Space Transportation System Research and Development Center, JAXA. http://www.rocket.jaxa.jp/fstrc/0c02.html.

- ↑ "Dawn Aerospace wins license for suborbital flights" (in en-US). 2020-12-09. https://spacenews.com/dawn-wins-spaceplane-license/.

- ↑ "Dawn Aerospace Mk-II Spaceplane Flight Testing Commences – Five Flights Complete". https://www.dawnaerospace.com/latest-news/mkii-flight-testing-commences.

- ↑ "Dawn Mk-II Aurora - Rocket-Powered Aircraft". https://www.dawnaerospace.com/spaceplane.

- ↑ "Scout Space and Dawn Aerospace Complete First Suborbital Spaceplane Surveillance Test Flight". https://www.dawnaerospace.com/latest-news/suborbital-sda-test-flight.

- ↑ "Dawn Aerospace Begins Taking Orders for Aurora Spaceplane: A Breakthrough Rocket-Powered Aircraft". https://www.dawnaerospace.com/latest-news/product-release-aurora-spaceplane.

- ↑ David, Leonard (9 November 2012). "China's Mystery Space Plane Project Stirs Up Questions". Space.com. http://www.space.com/18410-china-space-plane-project-mystery.html.

- ↑ Fisher, Richard Jr. (3 January 2008). "...And Races into Space". International Assessment and Strategy Center. http://www.strategycenter.net/research/pubID.175/pub_detail.asp.

- ↑ Fisher, Richard Jr. (17 December 2007). "Shenlong Space Plane Advances China's Military Space Potential". International Assessment and Strategy Center. http://www.strategycenter.net/research/pubID.174/pub_detail.asp.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (3 January 2008). "Invoking China to keep the shuttle alive". Space Politics. http://www.spacepolitics.com/2008/01/03/invoking-china-to-keep-the-shuttle-alive/.

- ↑ "China Details Cargo-toting Space Plane" (in en-US). https://www.leonarddavid.com/china-details-cargo-toting-space-plane/.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hsu, Jeremy (15 October 2008). "Europe Aims For Re-entry Spacecraft". Space.com. http://www.space.com/5978-europe-aims-entry-spacecraft.html.

- ↑ "The Reusability Flight Experiment (ReFEx)" (in en). https://www.dlr.de/en/sr/research-and-transfer/projects-and-missions/space-research/the-reusability-flight-experiment-refex.

- ↑ Parsonson, Andrew (2024-11-02). "Launch of DLR Reusable Flight Experiment Pushed to Late 2026" (in en-US). https://europeanspaceflight.com/launch-of-dlr-reusable-flight-experiment-pushed-to-late-2026/.

- ↑ Parsonson, Andrew (2024-08-06). "POLARIS and DLR to Explore Integrating Spaceplanes in Commercial Airspace" (in en-US). https://europeanspaceflight.com/polaris-and-dlr-to-explore-integrating-spaceplanes-in-commercial-airspace/.

- ↑ Parsonson, Andrew (2025-05-05). "POLARIS Spaceplanes Prepares for Key In-Flight Refuelling Milestone" (in en-US). https://europeanspaceflight.com/polaris-spaceplanes-prepares-for-key-in-flight-refuelling-milestone/.

- ↑ Parsonson, Andrew (2025-06-13). "Germany's POLARIS Spaceplanes Secures €5.4M in New Funding" (in en-US). https://europeanspaceflight.com/germanys-polaris-spaceplanes-secures-e5-4m-in-new-funding/.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Marín, Daniel (2025-07-07). "VORTEX, Aurora y Étoile, los nuevos aviones espaciales europeos" (in es). https://danielmarin.naukas.com/2025/07/08/vortex-aurora-y-etoile-los-nuevos-aviones-espaciales-europeos/.

- ↑ Parsonson, Andrew (2025-11-11). "OHB Establishes the European Spaceport Company" (in en-US). https://europeanspaceflight.com/ohb-establishes-the-european-spaceport-company/.

- ↑ "Dassault : voici à quoi ressemblera le futur avion spatial français" (in fr). 2025-06-17. https://www.lopinion.fr/international/dassault-vortex-le-rafale-du-futur-qui-volera-dans-lespace.

- ↑ Bourget 2025 : Dassault Aviation lève le voile sur son concept d’avion spatial, le Vortex

- ↑ "The European Space Agency and Dassault Aviation paving the way for potential collaborations" (in en). https://www.esa.int/Newsroom/Press_Releases/The_European_Space_Agency_and_Dassault_Aviation_paving_the_way_for_potential_collaborations.

- ↑ Parsonson, Andrew (2025-05-19). "CNES Awards Contract to French Spaceplane Startup" (in en-US). https://europeanspaceflight.com/cnes-awards-contract-to-french-spaceplane-startup/.

- ↑ "Two UK sites shortlisted for INVICTUS hypersonic test programme". https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/Shaping_the_Future/Two_UK_sites_shortlisted_for_INVICTUS_hypersonic_test_programme.

- ↑ "India's Reusable Launch Vehicle-Technology Demonstrator (RLV-TD), Successfully Flight Tested". Indian Space Research Organisation. 23 May 2016. http://www.isro.gov.in/update/23-may-2016/india%E2%80%99s-reusable-launch-vehicle-technology-demonstrator-rlv-td-successfully.

- ↑ "Reusable Launch Vehicle Autonomous Landing Mission (RLV LEX)". https://www.isro.gov.in/Reusable_launch_vehicle_autonomous_landing_mission.html.

- ↑ "Isro reusable launch vehicle's landing experiment successful; RLV closer to orbital re-entry mission". The Times of India. 2023-04-02. ISSN 0971-8257. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/isro-reusable-launch-vehicles-landing-experiment-successful-rlv-closer-to-orbital-re-entry-mission/articleshow/99181950.cms?from=mdr.

- ↑ Koichi, Yonemoto; Takahiro, Fujikawa; Toshiki, Morito; Joseph, Wang; Ahsan r, Choudhuri (2018), "Subscale Winged Rocket Development and Application to Future Reusable Space Transportation", Incas Bulletin 10: 161–172, doi:10.13111/2066-8201.2018.10.1.15, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323693460

- ↑ "NOVA Online | Stationed in the Stars | Inspired by Science Fiction". https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/station/inspired.html.

- ↑ Heppenheimer, T. A. (1999). "CHAPTER 1: SPACE STATIONS AND WINGED ROCKETS". https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4221/ch1.htm.

- ↑ Kass, Harrison (2021-06-21). "Boeing's X-20 Dyna-Soar Was The Air Force's 'Spaceplane' That Never Flew" (in en-US). https://thedebrief.org/boeings-x-20-dyna-soar-was-the-air-forces-spaceplane-that-never-flew/.

- ↑ "USAF X-20 "Dyna-Soar" Program Draftees | Spaceline" (in en-US). https://www.spaceline.org/united-states-manned-space-flight/us-astronaut-selection-drafts-and-qualifications/usaf-x-20-dyna-soar-program-draftees/.

- ↑ Hacker & Grimwood 1977, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Hacker & Grimwood 1977, pp. 145–148.

- ↑ Hacker & Grimwood 1977, pp. 171–173.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "X-30 National Aerospace Plane (NASP)". Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/irp/mystery/nasp.htm.

- ↑ "Black Horse". http://www.astronautix.com/lvs/blahorse.htm.

- ↑ Zubrin, Robert M.; Clapp, Mitchell Burnside (June 1995). "Black Horse: One Stop to Orbit". Analog Science Fiction and Fact 115 (7). http://www.risacher.org/bh/analog.html.

- ↑ "Two-Stage-to-Orbit 'Blackstar' System Shelved at Groom Lake? ." Scott, W., Aviation Week & Space Technology. 5 March 2006.

- ↑ Leonard, David (7 October 2011). "Secretive US X-37B Space Plane Could Evolve to Carry Astronauts". Space.com. http://www.space.com/13230-secretive-37b-space-plane-future-astronauts.html.

- ↑ Gordon, Yefim; Gunston, Bill (2000). Soviet X-planes. Leicester: Midland Publishers. ISBN 1-85780-099-0.

- ↑ "Russia Develops New Aircraft – Cosmoplane". Russia-InfoCentre. 27 February 2006. http://russia-ic.com/news/show/1925/.

- ↑ "Космоплан – самолет будущего". 3 November 2003. http://www.rususa.com/news/news.asp-nid-2632.

- ↑ Darling, David (2010). "MUSTARD (Multi-Unit Space Transport and Recovery Device)". http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/M/MUSTARD.html.

- ↑ "HOTOL History". Reaction Engines Limited. 2010. http://www.reactionengines.co.uk/bkgrnd.html.

- ↑ "Skylon FAQ". Reaction Engines Limited. 2010. http://www.reactionengines.co.uk/faq.html#q6.

- ↑ Unmeel Mehta, Michael Aftosmis, Jeffrey Bowles, and Shishir Pandya; Skylon Aerodynamics and SABRE Plumes, NASA, 20th AIAA International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies Conference 6–9 July 2015, 2015,

- ↑ "Big Test Looms for British Space Plane Concept". 18 April 2011. https://www.space.com/11414-skylon-space-plane-british-engine-test.html.

- ↑ "Bristol Spaceplanes Company Information". Bristol Spaceplanes. 2014. http://bristolspaceplanes.com/company/.

- ↑ Bayer, Martin (August 1995). "Hermes: Learning from our mistakes". Space Policy 11 (3): 171–180. doi:10.1016/0265-9646(95)00016-6. Bibcode: 1995SpPol..11..171B.

- ↑ "Saenger II". http://www.astronautix.com/s/saengerii.html.

- ↑ "Germany and Piloted Space Missions". Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/spp/guide/germany/piloted/index.html.

- ↑ McKee, Maggie (10 May 2004). "Europe's space shuttle passes early test". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn4975-europes-space-shuttle-passes-early-test/.

- ↑ "Launching the next generation of rockets". BBC News. 1 October 2004. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3699848.stm.

- ↑ Dujarric, C. (March 1999). "Possible Future European Launchers, A Process of Convergence". ESA Bulletin (European Space Agency) (97): 11–19. http://www.esa.int/esapub/bulletin/bullet97/dujarric.pdf.

- ↑ "FAST20XX (Future High-Altitude High-Speed Transport 20XX) / Space Engineering & Technology / Our Activities / ESA". Esa.int. 2 October 2012. http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Engineering_Technology/FAST20XX_Future_High-Altitude_High-Speed_Transport_20XX.

- ↑ "Europe unveils space plane for tourist market" (in en-US). NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna19211706.

- ↑ "Indian Scientists unveils space plane Avatar in US". Gujarat Science City. 10 July 2001. http://www.scity.gujarat.gov.in/plane-avatar.htm.

- ↑ "India Eyes New Spaceplane Concept". Space Daily. 8 August 2001. http://www.spacedaily.com/news/india-01i.html.

- ↑ "AVATAR- Hyper Plane to be built by INDIA". India's Military and Civilian Technological Advancements. 19 December 2011.

Bibliography

- Hacker, Barton C.; Grimwood, James M. (1977). On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. Washington, D.C.: NASA. NASA SP-4203. OCLC 3821896. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/cover.htm. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Kuczera, Heribert; Sacher, Peter W. (2011). Reusable Space Transportation Systems. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-89180-2.

External links

|