Monomorphism

In the context of abstract algebra or universal algebra, a monomorphism is an injective homomorphism. A monomorphism from X to Y is often denoted with the notation [math]\displaystyle{ X\hookrightarrow Y }[/math].

In the more general setting of category theory, a monomorphism (also called a monic morphism or a mono) is a left-cancellative morphism. That is, an arrow f : X → Y such that for all objects Z and all morphisms g1, g2: Z → X,

- [math]\displaystyle{ f \circ g_1 = f \circ g_2 \implies g_1 = g_2. }[/math]

Monomorphisms are a categorical generalization of injective functions (also called "one-to-one functions"); in some categories the notions coincide, but monomorphisms are more general, as in the examples below.

In the setting of posets intersections are idempotent: the intersection of anything with itself is itself. Monomorphisms generalize this property to arbitrary categories. A morphism is a monomorphism if it is idempotent with respect to pullbacks.

The categorical dual of a monomorphism is an epimorphism, that is, a monomorphism in a category C is an epimorphism in the dual category Cop. Every section is a monomorphism, and every retraction is an epimorphism.

Relation to invertibility

Left-invertible morphisms are necessarily monic: if l is a left inverse for f (meaning l is a morphism and [math]\displaystyle{ l \circ f = \operatorname{id}_{X} }[/math]), then f is monic, as

- [math]\displaystyle{ f \circ g_1 = f \circ g_2 \Rightarrow l\circ f\circ g_1 = l\circ f\circ g_2 \Rightarrow g_1 = g_2. }[/math]

A left-invertible morphism is called a split mono or a section.

However, a monomorphism need not be left-invertible. For example, in the category Group of all groups and group homomorphisms among them, if H is a subgroup of G then the inclusion f : H → G is always a monomorphism; but f has a left inverse in the category if and only if H has a normal complement in G.

A morphism f : X → Y is monic if and only if the induced map f∗ : Hom(Z, X) → Hom(Z, Y), defined by f∗(h) = f ∘ h for all morphisms h : Z → X, is injective for all objects Z.

Examples

Every morphism in a concrete category whose underlying function is injective is a monomorphism; in other words, if morphisms are actually functions between sets, then any morphism which is a one-to-one function will necessarily be a monomorphism in the categorical sense. In the category of sets the converse also holds, so the monomorphisms are exactly the injective morphisms. The converse also holds in most naturally occurring categories of algebras because of the existence of a free object on one generator. In particular, it is true in the categories of all groups, of all rings, and in any abelian category.

It is not true in general, however, that all monomorphisms must be injective in other categories; that is, there are settings in which the morphisms are functions between sets, but one can have a function that is not injective and yet is a monomorphism in the categorical sense. For example, in the category Div of divisible (abelian) groups and group homomorphisms between them there are monomorphisms that are not injective: consider, for example, the quotient map q : Q → Q/Z, where Q is the rationals under addition, Z the integers (also considered a group under addition), and Q/Z is the corresponding quotient group. This is not an injective map, as for example every integer is mapped to 0. Nevertheless, it is a monomorphism in this category. This follows from the implication q ∘ h = 0 ⇒ h = 0, which we will now prove. If h : G → Q, where G is some divisible group, and q ∘ h = 0, then h(x) ∈ Z, ∀ x ∈ G. Now fix some x ∈ G. Without loss of generality, we may assume that h(x) ≥ 0 (otherwise, choose −x instead). Then, letting n = h(x) + 1, since G is a divisible group, there exists some y ∈ G such that x = ny, so h(x) = n h(y). From this, and 0 ≤ h(x) < h(x) + 1 = n, it follows that

- [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq \frac{h(x)}{h(x) + 1} = h(y) \lt 1 }[/math]

Since h(y) ∈ Z, it follows that h(y) = 0, and thus h(x) = 0 = h(−x), ∀ x ∈ G. This says that h = 0, as desired.

To go from that implication to the fact that q is a monomorphism, assume that q ∘ f = q ∘ g for some morphisms f, g : G → Q, where G is some divisible group. Then q ∘ (f − g) = 0, where (f − g) : x ↦ f(x) − g(x). (Since (f − g)(0) = 0, and (f − g)(x + y) = (f − g)(x) + (f − g)(y), it follows that (f − g) ∈ Hom(G, Q)). From the implication just proved, q ∘ (f − g) = 0 ⇒ f − g = 0 ⇔ ∀ x ∈ G, f(x) = g(x) ⇔ f = g. Hence q is a monomorphism, as claimed.

Properties

- In a topos, every mono is an equalizer, and any map that is both monic and epic is an isomorphism.

- Every isomorphism is monic.

Related concepts

There are also useful concepts of regular monomorphism, extremal monomorphism, immediate monomorphism, strong monomorphism, and split monomorphism.

- A monomorphism is said to be regular if it is an equalizer of some pair of parallel morphisms.

- A monomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] is said to be extremal[1] if in each representation [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\varphi\circ\varepsilon }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] is an epimorphism, the morphism [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] is automatically an isomorphism.

- A monomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] is said to be immediate if in each representation [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mu'\circ\varepsilon }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \mu' }[/math] is a monomorphism and [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] is an epimorphism, the morphism [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] is automatically an isomorphism.

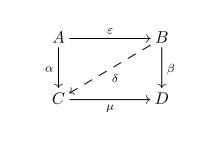

- A monomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \mu:C\to D }[/math] is said to be strong[1][2] if for any epimorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon:A\to B }[/math] and any morphisms [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha:A\to C }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta:B\to D }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \beta\circ\varepsilon=\mu\circ\alpha }[/math], there exists a morphism [math]\displaystyle{ \delta:B\to C }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \delta\circ\varepsilon=\alpha }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu\circ\delta=\beta }[/math].

- A monomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] is said to be split if there exists a morphism [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon\circ\mu=1 }[/math] (in this case [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] is called a left-sided inverse for [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math]).

Terminology

The companion terms monomorphism and epimorphism were originally introduced by Nicolas Bourbaki; Bourbaki uses monomorphism as shorthand for an injective function. Early category theorists believed that the correct generalization of injectivity to the context of categories was the cancellation property given above. While this is not exactly true for monic maps, it is very close, so this has caused little trouble, unlike the case of epimorphisms. Saunders Mac Lane attempted to make a distinction between what he called monomorphisms, which were maps in a concrete category whose underlying maps of sets were injective, and monic maps, which are monomorphisms in the categorical sense of the word. This distinction never came into general use.

Another name for monomorphism is extension, although this has other uses too.

See also

Notes

References

- Bergman, George (2015). An Invitation to General Algebra and Universal Constructions. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-11478-1. http://math.berkeley.edu/~gbergman/245/index.html.

- Borceux, Francis (1994). Handbook of Categorical Algebra. Volume 1: Basic Category Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521061193.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Monomorphism", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/m064800

- Van Oosten, Jaap (1995). "Basic Category Theory". Brics Lecture Series (BRICS, Computer Science Department, University of Aarhus). ISSN 1395-2048. http://www.math.uu.nl/people/jvoosten/syllabi/catsmoeder.pdf.

- Tsalenko, M.S.; Shulgeifer, E.G. (1974). Foundations of category theory. Nauka. ISBN 5-02-014427-4.

External links

|