Skinny triangle

In trigonometry, a skinny triangle is a triangle whose height is much greater than its base. The solution of such triangles can be greatly simplified by using the approximation that the sine of a small angle is equal to that angle in radians. The solution is particularly simple for skinny triangles that are also isosceles or right triangles: in these cases the need for trigonometric functions or tables can be entirely dispensed with.

The skinny triangle finds uses in surveying, astronomy, and shooting.

Isosceles triangle

| Large angles | Small angles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

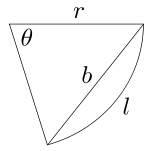

The approximated solution to the skinny isosceles triangle, referring to figure 1, is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ b \approx r \theta \, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{area} \approx \frac{1}{2} \theta r^2 \, }[/math]

This is based on the small-angle approximations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin\theta \approx \theta, \quad \theta \ll 1 \, }[/math]

and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cos\theta = \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta \right) \approx 1, \quad \theta \ll 1 }[/math]

when [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \theta }[/math] is in radians.

The proof of the skinny triangle solution follows from the small-angle approximation by applying the law of sines. Again referring to figure 1:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{b}{\sin\theta} = \frac{r}{\sin \left( \frac{\pi-\theta}{2} \right)} }[/math]

The term [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle \frac{\pi-\theta}{2} }[/math] represents the base angle of the triangle and is this value because the sum of the internal angles of any triangle (in this case the two base angles plus θ) are equal to π. Applying the small angle approximations to the law of sines above results in

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{b}{\theta} \approx \frac{r}{1} }[/math]

which is the desired result.

This result is equivalent to assuming that the length of the base of the triangle is equal to the length of the arc of circle of radius r subtended by angle θ. The error is 10% or less for angles less than about 43°,[2] and improves quadratically: when the angle decreases by a factor of k, the error decreases by k2.

The side-angle-side formula for the area of the triangle is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{area} = \frac{\sin\theta}{2} r^2 }[/math]

Applying the small angle approximations results in

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{area} \approx \frac{1}{2} \theta r^2 \, }[/math]

Right triangle

| Large angles | Small angles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The approximated solution to the right skinny triangle, referring to figure 3, is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ b \approx h \theta }[/math]

This is based on the small-angle approximation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tan\theta \approx \theta, \quad \theta \ll 1 }[/math]

which when substituted into the exact solution

- [math]\displaystyle{ b = h \tan\theta \ }[/math]

yields the desired result.

The error of this approximation is less than 10% for angles 31° or less.[3]

Applications

Applications of the skinny triangle occur in any situation where the distance to a far object is to be determined. This can occur in surveying, astronomy, and also has military applications.

Astronomy

The skinny triangle is frequently used in astronomy to measure the distance to Solar System objects. The base of the triangle is formed by the distance between two measuring stations and the angle θ is the parallax angle formed by the object as seen by the two stations. This baseline is usually very long for best accuracy; in principle the stations could be on opposite sides of the Earth. However, this distance is still short compared to the distance to the object being measured (the height of the triangle) and the skinny triangle solution can be applied and still achieve great accuracy. The alternative method of measuring the base angles is theoretically possible but not so accurate. The base angles are very nearly right angles and would need to be measured with much greater precision than the parallax angle in order to get the same accuracy.[4]

The same method of measuring parallax angles and applying the skinny triangle can be used to measure the distances to stars, at least the nearer ones. In the case of stars, however, a longer baseline than the diameter of the Earth is usually required. Instead of using two stations on the baseline, two measurements are made from the same station at different times of year. During the intervening period, the orbit of the Earth around the Sun moves the measuring station a great distance, so providing a very long baseline. This baseline can be as long as the major axis of the Earth's orbit or, equivalently, two astronomical units (AU). The distance to a star with a parallax angle of only one arcsecond measured on a baseline of one AU is a unit known as the parsec (pc) in astronomy and is equal to about 3.26 light years.[5] There is an inverse relationship between the distance in parsecs and the angle in arcseconds. For instance, two arcseconds corresponds to a distance of 0.5 pc and 0.5 arcsecond corresponds to a distance of two parsecs.[6]

Gunnery

The skinny triangle is useful in gunnery in that it allows a relationship to be calculated between the range and size of the target without the shooter needing to compute or look up any trigonometric functions. Military and hunting telescopic sights often have a reticle calibrated in milliradians, in this context usually called just mils or mil-dots. A target 1 metre in height and measuring 1 mil in the sight corresponds to a range of 1000 metres. There is an inverse relationship between the angle measured in a sniper's sight and the distance to target. For instance, if this same target measures 2 mils in the sight then the range is 500 metres.[7]

Another unit which is sometimes used on gunsights is the minute of arc (MOA). The distances corresponding to minutes of arc are not exact numbers in the metric system as they are with milliradians; however, there is a convenient approximate whole number correspondence in imperial units. A target 1 inch in height and measuring 1 MOA in the sight corresponds to a range of 100 yards.[7] Or, perhaps more usefully, a target 6 feet in height and measuring 4 MOA corresponds to a range of 1800 yards (just over a mile).

Aviation

A simple form of aviation navigation, dead reckoning, relies on making estimates of wind speeds aloft over long distances to calculate a desired heading. Since predicted or reported wind speeds are rarely accurate, corrections to the aircraft's heading need to be made at regular intervals. Skinny triangles form the basis of the 1 in 60 rule, which is "After travelling 60 miles, your heading is one degree off for every mile you're off course". "60" is very close to 180 / π = 57.30.

See also

- Small angle approximation

- Infinitesimal oscillations of a pendulum

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vasan (2004), p. 124.

- ↑ Abell, Morrison & Wolff (1987), pp. 414–415; Breithaupt (2000), p. 26.

- ↑ Holbrow et al. (2010), pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Abell, Morrison & Wolff (1987), p. 414.

- ↑ Abell, Morrison & Wolff (1987), Inside front cover.

- ↑ Abell, Morrison & Wolff (1987), p. 414–416, 418–419.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Warlow (1996), p. 87.

Bibliography

- Abell, George Ogden; Morrison, David; Wolff, Sidney C. (1987). Exploration of the Universe. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 0-03-005143-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=BXDvAAAAMAAJ.

- Breithaupt, Jim (2000). Physics for Advanced Level. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-7487-4315-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=xRJuOVmD7MsC&pg=PA26.

- Holbrow, Charles H.; Lloyd, James N.; Amato, Joseph C.; Galvez, Enrique; Parks, Beth (2010). Modern Introductory Physics. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 0-387-79079-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=KLT_FyQyimUC.

- Vasan, Srini (2004). Basics of Photonics and Optics. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4120-4138-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=AB5fi0_TMrgC.

- Warlow, Tom A. (1996). Firearms, the law and forensic ballistics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7484-0432-5.

|