CAT(k) space

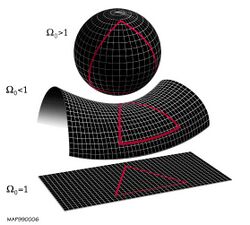

In mathematics, a [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\operatorname{\textbf{CAT}}}(k) }[/math] space, where [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is a real number, is a specific type of metric space. Intuitively, triangles in a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space (with [math]\displaystyle{ k\lt 0 }[/math]) are "slimmer" than corresponding "model triangles" in a standard space of constant curvature [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. In a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space, the curvature is bounded from above by [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. A notable special case is [math]\displaystyle{ k=0 }[/math]; complete [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] spaces are known as "Hadamard spaces" after the France mathematician Jacques Hadamard.

Originally, Aleksandrov called these spaces “[math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{R}_k }[/math] domains”. The terminology [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] was coined by Mikhail Gromov in 1987 and is an acronym for Élie Cartan, Aleksandr Danilovich Aleksandrov and Victor Andreevich Toponogov (although Toponogov never explored curvature bounded above in publications).

Definitions

For a real number [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ M_k }[/math] denote the unique complete simply connected surface (real 2-dimensional Riemannian manifold) with constant curvature [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. Denote by [math]\displaystyle{ D_k }[/math] the diameter of [math]\displaystyle{ M_k }[/math], which is [math]\displaystyle{ \infty }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ k \leq 0 }[/math] and is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\pi}{\sqrt{k}} }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ k\gt 0 }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ (X,d) }[/math] be a geodesic metric space, i.e. a metric space for which every two points [math]\displaystyle{ x,y\in X }[/math] can be joined by a geodesic segment, an arc length parametrized continuous curve [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma\colon [a,b] \to X,\ \gamma(a) = x,\ \gamma(b) = y }[/math], whose length

- [math]\displaystyle{ L(\gamma) = \sup \left\{ \left. \sum_{i = 1}^{r} d \big( \gamma(t_{i-1}), \gamma(t_{i}) \big) \right| a = t_{0} \lt t_{1} \lt \cdots \lt t_{r} = b, r\in \mathbb{N} \right\} }[/math]

is precisely [math]\displaystyle{ d(x,y) }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math] be a triangle in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with geodesic segments as its sides. [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math] is said to satisfy the [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\operatorname{\textbf{CAT}}}(k) }[/math] inequality if there is a comparison triangle [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta' }[/math] in the model space [math]\displaystyle{ M_k }[/math], with sides of the same length as the sides of [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math], such that distances between points on [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math] are less than or equal to the distances between corresponding points on [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta' }[/math].

The geodesic metric space [math]\displaystyle{ (X,d) }[/math] is said to be a [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\operatorname{\textbf{CAT}}}(k) }[/math] space if every geodesic triangle [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with perimeter less than [math]\displaystyle{ 2D_k }[/math] satisfies the [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] inequality. A (not-necessarily-geodesic) metric space [math]\displaystyle{ (X,\,d) }[/math] is said to be a space with curvature [math]\displaystyle{ \leq k }[/math] if every point of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] has a geodesically convex [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] neighbourhood. A space with curvature [math]\displaystyle{ \leq 0 }[/math] may be said to have non-positive curvature.

Examples

- Any [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space [math]\displaystyle{ (X,d) }[/math] is also a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(\ell) }[/math] space for all [math]\displaystyle{ \ell\gt k }[/math]. In fact, the converse holds: if [math]\displaystyle{ (X,d) }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(\ell) }[/math] space for all [math]\displaystyle{ \ell\gt k }[/math], then it is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space.

- The [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-dimensional Euclidean space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}^n }[/math] with its usual metric is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] space. More generally, any real inner product space (not necessarily complete) is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] space; conversely, if a real normed vector space is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space for some real [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math], then it is an inner product space.

- The [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-dimensional hyperbolic space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{H}^n }[/math] with its usual metric is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(-1) }[/math] space, and hence a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] space as well.

- The [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-dimensional unit sphere [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{S}^n }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(1) }[/math] space.

- More generally, the standard space [math]\displaystyle{ M_k }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space. So, for example, regardless of dimension, the sphere of radius [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] (and constant curvature [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{r^2} }[/math]) is a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}\left(\frac{1}{r^2}\right) }[/math] space. Note that the diameter of the sphere is [math]\displaystyle{ \pi r }[/math] (as measured on the surface of the sphere) not [math]\displaystyle{ 2r }[/math] (as measured by going through the centre of the sphere).

- The punctured plane [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi = \mathbf{E}^2\backslash\{\mathbf{0}\} }[/math] is not a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] space since it is not geodesically convex (for example, the points [math]\displaystyle{ (0,1) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (0,-1) }[/math] cannot be joined by a geodesic in [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] with arc length 2), but every point of [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] does have a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] geodesically convex neighbourhood, so [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] is a space of curvature [math]\displaystyle{ \leq 0 }[/math].

- The closed subspace [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}^3 }[/math] given by [math]\displaystyle{ X = \mathbf{E}^{3} \setminus \{ (x, y, z) \mid x \gt 0, y \gt 0 \text{ and } z \gt 0 \} }[/math] equipped with the induced length metric is not a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space for any [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math].

- Any product of [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math] spaces is [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(0) }[/math]. (This does not hold for negative arguments.)

Hadamard spaces

As a special case, a complete CAT(0) space is also known as a Hadamard space; this is by analogy with the situation for Hadamard manifolds. A Hadamard space is contractible (it has the homotopy type of a single point) and, between any two points of a Hadamard space, there is a unique geodesic segment connecting them (in fact, both properties also hold for general, possibly incomplete, CAT(0) spaces). Most importantly, distance functions in Hadamard spaces are convex: if [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_1, \sigma_2 }[/math] are two geodesics in X defined on the same interval of time I, then the function [math]\displaystyle{ I\to \R }[/math] given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ t \mapsto d \big( \sigma_{1} (t), \sigma_{2} (t) \big) }[/math]

is convex in t.

Properties of CAT(k) spaces

Let [math]\displaystyle{ (X,d) }[/math] be a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space. Then the following properties hold:

- Given any two points [math]\displaystyle{ x,y\in X }[/math] (with [math]\displaystyle{ d(x,y)\lt D_k }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ k\gt 0 }[/math]), there is a unique geodesic segment that joins [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math]; moreover, this segment varies continuously as a function of its endpoints.

- Every local geodesic in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with length at most [math]\displaystyle{ D_k }[/math] is a geodesic.

- The [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]-balls in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] of radius less than [math]\displaystyle{ D_k/2 }[/math] are (geodesically) convex.

- The [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]-balls in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] of radius less than [math]\displaystyle{ D_k }[/math] are contractible.

- Approximate midpoints are close to midpoints in the following sense: for every [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda \lt D_k }[/math] and every [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon \gt 0 }[/math] there exists a [math]\displaystyle{ \delta = \delta(k,\lambda,\epsilon) \gt 0 }[/math] such that, if [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is the midpoint of a geodesic segment from [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ d(x,y)\leq \lambda }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \max \bigl\{ d(x, m'), d(y, m') \bigr\} \leq \frac1{2} d(x, y) + \delta, }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ d(m,m') \lt \epsilon }[/math].

- It follows from these properties that, for [math]\displaystyle{ k\leq 0 }[/math] the universal cover of every [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space is contractible; in particular, the higher homotopy groups of such a space are trivial. As the example of the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-sphere [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{S}^n }[/math] shows, there is, in general, no hope for a [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CAT}(k) }[/math] space to be contractible if [math]\displaystyle{ k \gt 0 }[/math].

Surfaces of non-positive curvature

In a region where the curvature of the surface satisfies K ≤ 0, geodesic triangles satisfy the CAT(0) inequalities of comparison geometry, studied by Cartan, Alexandrov and Toponogov, and considered later from a different point of view by Bruhat and Tits. Thanks to the vision of Gromov, this characterisation of non-positive curvature in terms of the underlying metric space has had a profound impact on modern geometry and in particular geometric group theory. Many results known for smooth surfaces and their geodesics, such as Birkhoff's method of constructing geodesics by his curve-shortening process or van Mangoldt and Hadamard's theorem that a simply connected surface of non-positive curvature is homeomorphic to the plane, are equally valid in this more general setting.

Alexandrov's comparison inequality

The simplest form of the comparison inequality, first proved for surfaces by Alexandrov around 1940, states that

The distance between a vertex of a geodesic triangle and the midpoint of the opposite side is always less than the corresponding distance in the comparison triangle in the plane with the same side-lengths.

The inequality follows from the fact that if c(t) describes a geodesic parametrized by arclength and a is a fixed point, then

- f(t) = d(a,c(t))2 − t2

is a convex function, i.e.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{f}(t) \ge 0. }[/math]

Taking geodesic polar coordinates with origin at a so that ‖c(t)‖ = r(t), convexity is equivalent to

- [math]\displaystyle{ r\ddot{r} + \dot{r}^2 \ge 1. }[/math]

Changing to normal coordinates u, v at c(t), this inequality becomes

- u2 + H−1Hrv2 ≥ 1,

where (u,v) corresponds to the unit vector ċ(t). This follows from the inequality Hr ≥ H, a consequence of the non-negativity of the derivative of the Wronskian of H and r from Sturm–Liouville theory.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ Berger 2004; Jost, Jürgen (1997), Nonpositive curvature: geometric and analytic aspects, Lectures in Mathematics, ETH Zurich, Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-0-8176-5736-9

- Alexander, Stephanie; Kapovitch, Vitali; Petrunin, Anton. "Alexandrov Geometry, Chapter 7" (PDF). http://www.math.uiuc.edu/~sba/the-defs-CBA.pdf. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- Alexander, Stephanie; Kapovitch, Vitali; Petrunin, Anton. "Invitation to Alexandrov geometry: CAT[0] spaces". arXiv:1701.03483 [math.DG].

- Ballmann, Werner (1995). Lectures on spaces of nonpositive curvature. DMV Seminar 25. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag. pp. viii+112. ISBN 3-7643-5242-6.

- Berger, Marcel (2004). A panoramic view of Riemannian geometry. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-65317-2.

- Bridson, Martin R.; Haefliger, André (1999). Metric spaces of non-positive curvature. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences] 319. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. xxii+643. ISBN 3-540-64324-9.

- Gromov, Mikhail (1987). "Hyperbolic groups". Essays in group theory. Math. Sci. Res. Inst. Publ. 8. New York: Springer. pp. 75–263.

- Hindawi, Mohamad A. (2005). Asymptotic invariants of Hadamard manifolds. University of Pennsylvania: PhD thesis. http://www.math.upenn.edu/grad/dissertations/HindawiThesis.pdf.

|