Roman surface

This article is written like a research paper or scientific journal that may use overly technical terms or may not be written like an encyclopedic article. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics, the Roman surface or Steiner surface is a self-intersecting mapping of the real projective plane into three-dimensional space, with an unusually high degree of symmetry. This mapping is not an immersion of the projective plane; however, the figure resulting from removing six singular points is one. Its name arises because it was discovered by Jakob Steiner when he was in Rome in 1844.[1]

The simplest construction is as the image of a sphere centered at the origin under the map [math]\displaystyle{ f(x,y,z)=(yz,xz,xy). }[/math] This gives an implicit formula of

- [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 y^2 + y^2 z^2 + z^2 x^2 - r^2 x y z = 0. \, }[/math]

Also, taking a parametrization of the sphere in terms of longitude (θ) and latitude (φ), gives parametric equations for the Roman surface as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ x=r^{2} \cos \theta \cos \varphi \sin \varphi }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ y=r^{2} \sin \theta \cos \varphi \sin \varphi }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ z=r^{2} \cos \theta \sin \theta \cos^{2} \varphi }[/math]

The origin is a triple point, and each of the xy-, yz-, and xz-planes are tangential to the surface there. The other places of self-intersection are double points, defining segments along each coordinate axis which terminate in six pinch points. The entire surface has tetrahedral symmetry. It is a particular type (called type 1) of Steiner surface, that is, a 3-dimensional linear projection of the Veronese surface.

Derivation of implicit formula

For simplicity we consider only the case r = 1. Given the sphere defined by the points (x, y, z) such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1,\, }[/math]

we apply to these points the transformation T defined by [math]\displaystyle{ T(x, y, z) = (y z, z x, x y) = (U,V,W),\, }[/math] say.

But then we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} U^2 V^2 + V^2 W^2 + W^2 U^2 & = z^2 x^2 y^4 + x^2 y^2 z^4 + y^2 z^2 x^4 = (x^2 + y^2 + z^2)(x^2 y^2 z^2) \\[8pt] & = (1)(x^2 y^2 z^2) = (xy) (yz) (zx) = U V W, \end{align} }[/math]

and so [math]\displaystyle{ U^2 V^2 + V^2 W^2 + W^2 U^2 - U V W = 0\, }[/math] as desired.

Conversely, suppose we are given (U, V, W) satisfying

(*) [math]\displaystyle{ U^2 V^2 + V^2 W^2 + W^2 U^2 - U V W = 0.\, }[/math]

We prove that there exists (x,y,z) such that

(**) [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1,\, }[/math]

for which [math]\displaystyle{ U = x y, V = y z, W = z x,\, }[/math]

with one exception: In case 3.b. below, we show this cannot be proved.

1. In the case where none of U, V, W is 0, we can set

- [math]\displaystyle{ x = \sqrt{\frac{WU}{V}},\ y = \sqrt{\frac{UV}{W}},\ z = \sqrt{\frac{VW}{U}}.\, }[/math]

(Note that (*) guarantees that either all three of U, V, W are positive, or else exactly two are negative. So these square roots are of positive numbers.)

It is easy to use (*) to confirm that (**) holds for x, y, z defined this way.

2. Suppose that W is 0. From (*) this implies [math]\displaystyle{ U^2 V^2 = 0\, }[/math]

and hence at least one of U, V must be 0 also. This shows that is it impossible for exactly one of U, V, W to be 0.

3. Suppose that exactly two of U, V, W are 0. Without loss of generality we assume

(***)[math]\displaystyle{ U \neq 0, V = W = 0.\, }[/math]

It follows that [math]\displaystyle{ z = 0,\, }[/math]

(since [math]\displaystyle{ z \neq 0,\, }[/math] implies that [math]\displaystyle{ x = y = 0,\, }[/math] and hence [math]\displaystyle{ U = 0,\, }[/math] contradicting (***).)

a. In the subcase where

- [math]\displaystyle{ |U| \leq \frac{1}{2}, }[/math]

if we determine x and y by

- [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 = \frac{1 + \sqrt{1 - 4 U^2}}{2} }[/math]

and [math]\displaystyle{ y^2 = \frac{1 - \sqrt{1 - 4 U^2}}{2}, }[/math]

this ensures that (*) holds. It is easy to verify that [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 y^2 = U^2,\, }[/math]

and hence choosing the signs of x and y appropriately will guarantee [math]\displaystyle{ x y = U.\, }[/math]

Since also [math]\displaystyle{ y z = 0 = V\text{ and }z x = 0 = W,\, }[/math]

this shows that this subcase leads to the desired converse.

b. In this remaining subcase of the case 3., we have [math]\displaystyle{ |U| \gt \frac{1}{2}. }[/math]

Since [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + y^2 = 1,\, }[/math]

it is easy to check that [math]\displaystyle{ xy \leq \frac{1}{2}, }[/math]

and thus in this case, where [math]\displaystyle{ |U| \gt 1/2,\ V = W = 0, }[/math]

there is no (x, y, z) satisfying [math]\displaystyle{ U = xy,\ V = yz,\ W =zx. }[/math]

Hence the solutions (U, 0, 0) of the equation (*) with [math]\displaystyle{ |U| \gt \frac12 }[/math]

and likewise, (0, V, 0) with [math]\displaystyle{ |V| \gt \frac12 }[/math]

and (0, 0, W) with [math]\displaystyle{ |W| \gt \frac12 }[/math]

(each of which is a noncompact portion of a coordinate axis, in two pieces) do not correspond to any point on the Roman surface.

4. If (U, V, W) is the point (0, 0, 0), then if any two of x, y, z are zero and the third one has absolute value 1, clearly [math]\displaystyle{ (xy, yz, zx) = (0, 0, 0) = (U, V, W)\, }[/math] as desired.

This covers all possible cases.

Derivation of parametric equations

Let a sphere have radius r, longitude φ, and latitude θ. Then its parametric equations are

- [math]\displaystyle{ x = r \, \cos \theta \, \cos \phi, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ y = r \, \cos \theta \, \sin \phi, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ z = r \, \sin \theta. }[/math]

Then, applying transformation T to all the points on this sphere yields

- [math]\displaystyle{ x' = y z = r^2 \, \cos \theta \, \sin \theta \, \sin \phi, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ y' = z x = r^2 \, \cos \theta \, \sin \theta \, \cos \phi, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ z' = x y = r^2 \, \cos^2 \theta \, \cos \phi \, \sin \phi, }[/math]

which are the points on the Roman surface. Let φ range from 0 to 2π, and let θ range from 0 to π/2.

Relation to the real projective plane

The sphere, before being transformed, is not homeomorphic to the real projective plane, RP2. But the sphere centered at the origin has this property, that if point (x,y,z) belongs to the sphere, then so does the antipodal point (-x,-y,-z) and these two points are different: they lie on opposite sides of the center of the sphere.

The transformation T converts both of these antipodal points into the same point,

- [math]\displaystyle{ T : (x, y, z) \rightarrow (y z, z x, x y), }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ T : (-x, -y, -z) \rightarrow ((-y) (-z), (-z) (-x), (-x) (-y)) = (y z, z x, x y). }[/math]

Since this is true of all points of S2, then it is clear that the Roman surface is a continuous image of a "sphere modulo antipodes". Because some distinct pairs of antipodes are all taken to identical points in the Roman surface, it is not homeomorphic to RP2, but is instead a quotient of the real projective plane RP2 = S2 / (x~-x). Furthermore, the map T (above) from S2 to this quotient has the special property that it is locally injective away from six pairs of antipodal points. Or from RP2 the resulting map making this an immersion of RP2 — minus six points — into 3-space.

Structure of the Roman surface

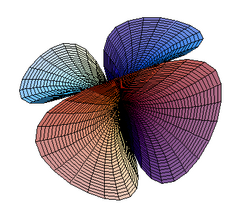

The Roman surface has four bulbous "lobes", each one on a different corner of a tetrahedron.

A Roman surface can be constructed by splicing together three hyperbolic paraboloids and then smoothing out the edges as necessary so that it will fit a desired shape (e.g. parametrization).

Let there be these three hyperbolic paraboloids:

- x = yz,

- y = zx,

- z = xy.

These three hyperbolic paraboloids intersect externally along the six edges of a tetrahedron and internally along the three axes. The internal intersections are loci of double points. The three loci of double points: x = 0, y = 0, and z = 0, intersect at a triple point at the origin.

For example, given x = yz and y = zx, the second paraboloid is equivalent to x = y/z. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ y z = {y \over z} }[/math]

and either y = 0 or z2 = 1 so that z = ±1. Their two external intersections are

- x = y, z = 1;

- x = −y, z = −1.

Likewise, the other external intersections are

- x = z, y = 1;

- x = −z, y = −1;

- y = z, x = 1;

- y = −z, x = −1.

Let us see the pieces being put together. Join the paraboloids y = xz and x = yz. The result is shown in Figure 1.

The paraboloid y = x z is shown in blue and orange. The paraboloid x = y z is shown in cyan and purple. In the image the paraboloids are seen to intersect along the z = 0 axis. If the paraboloids are extended, they should also be seen to intersect along the lines

- z = 1, y = x;

- z = −1, y = −x.

The two paraboloids together look like a pair of orchids joined back-to-back.

Now run the third hyperbolic paraboloid, z = xy, through them. The result is shown in Figure 2.

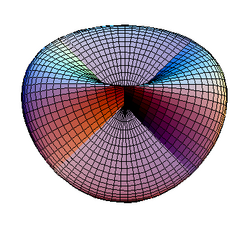

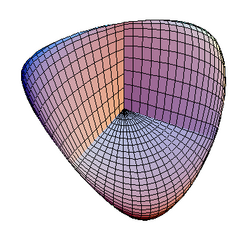

On the west-southwest and east-northeast directions in Figure 2 there are a pair of openings. These openings are lobes and need to be closed up. When the openings are closed up, the result is the Roman surface shown in Figure 3.

A pair of lobes can be seen in the West and East directions of Figure 3. Another pair of lobes are hidden underneath the third (z = xy) paraboloid and lie in the North and South directions.

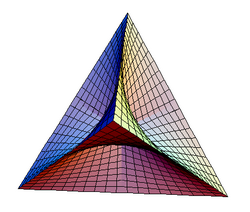

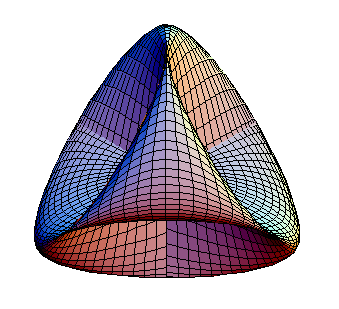

If the three intersecting hyperbolic paraboloids are drawn far enough that they intersect along the edges of a tetrahedron, then the result is as shown in Figure 4.

One of the lobes is seen frontally—head on—in Figure 4. The lobe can be seen to be one of the four corners of the tetrahedron.

If the continuous surface in Figure 4 has its sharp edges rounded out—smoothed out—then the result is the Roman surface in Figure 5.

One of the lobes of the Roman surface is seen frontally in Figure 5, and its bulbous – balloon-like—shape is evident.

If the surface in Figure 5 is turned around 180 degrees and then turned upside down, the result is as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows three lobes seen sideways. Between each pair of lobes there is a locus of double points corresponding to a coordinate axis. The three loci intersect at a triple point at the origin. The fourth lobe is hidden and points in the direction directly opposite from the viewer. The Roman surface shown at the top of this article also has three lobes in sideways view.

One-sidedness

The Roman surface is non-orientable, i.e. one-sided. This is not quite obvious. To see this, look again at Figure 3.

Imagine an ant on top of the "third" hyperbolic paraboloid, z = x y. Let this ant move North. As it moves, it will pass through the other two paraboloids, like a ghost passing through a wall. These other paraboloids only seem like obstacles due to the self-intersecting nature of the immersion. Let the ant ignore all double and triple points and pass right through them. So the ant moves to the North and falls off the edge of the world, so to speak. It now finds itself on the northern lobe, hidden underneath the third paraboloid of Figure 3. The ant is standing upside-down, on the "outside" of the Roman surface.

Let the ant move towards the Southwest. It will climb a slope (upside-down) until it finds itself "inside" the Western lobe. Now let the ant move in a Southeastern direction along the inside of the Western lobe towards the z = 0 axis, always above the x-y plane. As soon as it passes through the z = 0 axis the ant will be on the "outside" of the Eastern lobe, standing rightside-up.

Then let it move Northwards, over "the hill", then towards the Northwest so that it starts sliding down towards the x = 0 axis. As soon as the ant crosses this axis it will find itself "inside" the Northern lobe, standing right side up. Now let the ant walk towards the North. It will climb up the wall, then along the "roof" of the Northern lobe. The ant is back on the third hyperbolic paraboloid, but this time under it and standing upside-down. (Compare with Klein bottle.)

Double, triple, and pinching points

The Roman surface has four "lobes". The boundaries of each lobe are a set of three lines of double points. Between each pair of lobes there is a line of double points. The surface has a total of three lines of double points, which lie (in the parametrization given earlier) on the coordinate axes. The three lines of double points intersect at a triple point which lies on the origin. The triple point cuts the lines of double points into a pair of half-lines, and each half-line lies between a pair of lobes. One might expect from the preceding statements that there could be up to eight lobes, one in each octant of space which has been divided by the coordinate planes. But the lobes occupy alternating octants: four octants are empty and four are occupied by lobes.

If the Roman surface were to be inscribed inside the tetrahedron with least possible volume, one would find that each edge of the tetrahedron is tangent to the Roman surface at a point, and that each of these six points happens to be a Whitney singularity. These singularities, or pinching points, all lie at the edges of the three lines of double points, and they are defined by this property: that there is no plane tangent to any surface at the singularity.

See also

- Boy's surface – an immersion of the projective plane without cross-caps.

- Tetrahemihexahedron – a polyhedron very similar to the Roman surface.

References

- ↑ Coffman, Adam. "Steiner Roman Surfaces". Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne. http://old.nationalcurvebank.org/romansurfaces/romansurfaces.htm.

General references

- A. Coffman, A. Schwartz, and C. Stanton: The Algebra and Geometry of Steiner and other Quadratically Parametrizable Surfaces. In Computer Aided Geometric Design (3) 13 (April 1996), p. 257-286

- Bert Jüttler, Ragni Piene: Geometric Modeling and Algebraic Geometry. Springer 2008, ISBN:978-3-540-72184-0, p. 30 (restricted online copy, p. 30, at Google Books)

External links

- A. Coffman, "Steiner Surfaces"

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Roman Surface". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/RomanSurface.html.

- Roman Surfaces at the National Curve Bank (website of the California State University)

- Ashay Dharwadker, Heptahedron and Roman Surface, Electronic Geometry Models, 2004.

|