Astronomy:Theta Librae

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Libra |

| Right ascension | 15h 53m 49.53806s[1] |

| Declination | –16° 43′ 45.4582″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 4.136[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G9IIIb[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.82[4] |

| B−V color index | +1.01[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 4.56±0.25[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +100.33[1] mas/yr Dec.: +135.02[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 19.36 ± 0.15[6] mas |

| Distance | 168 ± 1 ly (51.7 ± 0.4 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 0.665[2] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.47[7] M☉ |

| Radius | 12.27[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 68.1[7] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 2.44[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 4,739[7] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | –0.35[7] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 0.0[5] km/s |

| Age | 3.4[7] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

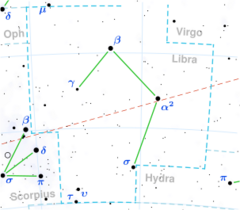

θ Librae, Latinised as Theta Librae, is a single[9] star in the southern zodiac constellation of Libra, near the constellation border with Scorpius. It is visible to the naked eye as a faint, orange-hued star with an apparent visual magnitude of 4.14.[2] The distance to this star is approximately 168 light years, as determined by parallax, and it is drifting further away with a radial velocity of 5 km/s.[5] The position of this star near the ecliptic means it is subject to lunar occultations.[10]

This object is an aging giant star with a stellar classification of G9IIIb.[3] Having exhausted the supply of hydrogen at its core, it has cooled and expanded; at present it has 12.3 times the girth of the Sun.[7] The star has an estimated mass about 47% greater than the Sun. It is radiating about 68 times the luminosity of the Sun from its photosphere at an effective temperature of about 4,739 K.[7] It is probably on the red giant branch, which indicates it is generating energy through hydrogen fusion in a shell outside an inert helium core.[7] However, there is a 41% chance that it is a red clump giant on the horizontal branch,[2] which would mean it was somewhat older and less massive.[7] It has sometimes been classified spectroscopically as a subgiant, but detailed study shows that it is too cool and luminous to be on the subgiant branch.[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Brown, A. G. A. (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 616: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Bibcode: 2018A&A...616A...1G. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Liu, Y. J. et al. (2007). "The abundances of nearby red clump giants". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 382 (2): 553–66. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11852.x. Bibcode: 2007MNRAS.382..553L.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Keenan, Philip C.; McNeil, Raymond C. (1989). "The Perkins catalog of revised MK types for the cooler stars". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 71: 245. doi:10.1086/191373. Bibcode: 1989ApJS...71..245K.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Johnson, H. L. et al. (1966). "UBVRIJKL photometry of the bright stars". Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory 4 (99): 99. Bibcode: 1966CoLPL...4...99J.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Massarotti, Alessandro et al. (January 2008), "Rotational and Radial Velocities for a Sample of 761 HIPPARCOS Giants and the Role of Binarity", The Astronomical Journal 135 (1): 209–231, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/1/209, Bibcode: 2008AJ....135..209M

- ↑ van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Reffert, Sabine; Bergmann, Christoph; Quirrenbach, Andreas; Trifonov, Trifon; Künstler, Andreas (2015). "Precise radial velocities of giant stars. VII. Occurrence rate of giant extrasolar planets as a function of mass and metallicity". Astronomy and Astrophysics 574: A116. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322360. Bibcode: 2015A&A...574A.116R.

- ↑ "tet Lib". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=tet+Lib.

- ↑ Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (September 2008). "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 389 (2): 869–879. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x. Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.389..869E.

- ↑ Edwards, D. A. et al. (April 1980). "Photoelectric observations of lunar occultations. XI.". Astronomical Journal 85: 478–489. doi:10.1086/112700. Bibcode: 1980AJ.....85..478E.

- ↑ Thorén, P.; Edvardsson, B.; Gustafsson, B. (2004). "Subgiants as probes of galactic chemical evolution". Astronomy and Astrophysics 425: 187–206. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20040421. Bibcode: 2004A&A...425..187T.

|