Major explorations after the Age of Discovery

Major explorations of Earth continued after the Age of Discovery. By the early seventeenth century, vessels were sufficiently well built and their navigators competent enough to travel to virtually anywhere on the planet by sea. In the 17th century, Dutch explorers such as Willem Jansz and Abel Tasman explored the coasts of Australia . Spanish expeditions from Peru explored the South Pacific and discovered archipelagos such as Vanuatu and the Pitcairn Islands. Luis Vaez de Torres chartered the coasts of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, and discovered the strait that bears his name. European naval exploration mapped the western and northern coasts of Australia, but the east coast had to wait for over a century. Eighteenth-century British explorer James Cook mapped much of Polynesia and traveled as far north as Alaska and as far south as the Antarctic Circle. In the later 18th century, the Pacific became a focus of renewed interest, with Spanish expeditions, followed by Northern European ones, reaching the coasts of northern British Columbia and Alaska. Voyages into the continents took longer. The centers of the Americas had been reached by the mid-16th century, although there were unexplored areas until the 18th and 19th centuries. Australia's and Africa's deep interiors were not explored by Europeans until the mid- to late 19th and early 20th centuries, due to a lack of trade potential, and to serious problems with contagious tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa's case. Finally, Antarctica's interior was explored, with the North and South Poles reached in the 20th century.

History

James Cook's Pacific Ocean exploration (1768–1779)

British explorer James Cook, who had been the first to map the North Atlantic island of Newfoundland, spent a dozen years in the Pacific Ocean. He made great contributions to European knowledge of the area, and his more accurate navigational charting of large areas of the ocean was a major achievement.

Cook made three voyages to the Pacific, including the first European contact with the eastern coastline of Australia and the Hawaiian Islands (although oral tradition seems to point towards a far earlier Spanish expedition having achieved the latter), as well as the first recorded circumnavigation of New Zealand.[1]

Cook was the first European to have extensive contact with various people of the Pacific. He correctly concluded there was a relationship among all the people in the Pacific, despite their being separated by thousands of miles of ocean (see Malayo-Polynesian languages). In New Zealand the coming of Cook is often used to signify the onset of colonization.[2][3] He also theorised that Polynesians originated from Asia, which was later proved to be correct by scientist Bryan Sykes.[4]

Cook was accompanied by many scientists, whose observations and discoveries added to the importance of the voyages. Two botanists went on the first voyage, Englishman Joseph Banks and Swedish Daniel Solander, between them collecting over 3,000 plant species. Banks became one of the strongest promoters of the settlement of Australia by the British, based on his own personal observations. Cook was also accompanied by artists. Sydney Parkinson completed 264 drawings before his death near the end of the first voyage; these were of immense scientific value to British botanists.[2] Cook's second expedition included the artist William Hodges, who produced notable landscape paintings of Tahiti, Easter Island, and other locations.

Mapping and measuring

To create accurate maps, latitude and longitude need to be known. Navigators had been able to work out latitude accurately for centuries by measuring the angle of the Sun or a star above the horizon with an instrument such as a backstaff or quadrant. Longitude was more difficult to measure accurately because it requires precise knowledge of the time difference between points on the surface of the Earth. Earth turns a full 360 degrees relative to the sun each day. Thus longitude corresponds to time: 15 degrees every hour, or 1 degree every 4 minutes.

Cook gathered accurate longitude measurements during his first voyage with the help of astronomer Charles Green and by using the newly published Nautical Almanac tables, via the lunar distance method — measuring the angular distance from the Moon to either the Sun during daytime or one of eight bright stars during night-time to determine the time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, and comparing that to his local time determined via the altitude of the Sun, Moon, or stars. On his second voyage Cook used the K1 chronometer made by Larcum Kendall. It was a copy of the H4 clock made by John Harrison, which proved to be the first to keep accurate time at sea when used on the ship Deptford's journey to Jamaica, 1761–1762.

Scientific Surveys in Central America and the Pacific

Alexander von Humboldt (1799–1804)

Between 1799 and 1804, Baron Alexander von Humboldt a German naturalist and explorer, traveled extensively in Spanish America, under the protection of king Charles IV of Spain. Humboldt intended to investigate how the forces of nature interact with one another and find out about the unity of nature. His expedition may be regarded as having laid the foundation of the sciences of physical geography and meteorology, exploring and describing for the first time in a manner generally considered to be a modern scientific point of view.[5]

As a consequence of his explorations, von Humboldt described many geographical features and species of life that were hitherto unknown to Europeans and his quantitative work on botanical geography was foundational to the field of biogeography. By his delineation of "isothermal lines", in 1817 he devised the means of comparing the climatic conditions of various countries, and to the detection of the more complicated law governing atmospheric disturbances in higher latitudes; he discovered the decrease in intensity of Earth's magnetic field from the poles to the equator. His attentive study of the volcanoes of the New World, showed that they fell naturally into linear groups, presumably corresponding with vast subterranean fissures, and he demonstrated the igneous origin of rocks.[citation needed] He was one of the first to propose that the lands bordering the Atlantic Ocean were once joined (South America and Africa in particular). The details and findings of Humboldt's journey were published in a set of 30 volumes over 21 years, his Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equatorial Regions of the New Continent. Later, his five-volume work, Cosmos: A Sketch for a Physical Description of the Universe (1845), attempted to unify the various branches of scientific knowledge.[citation needed]

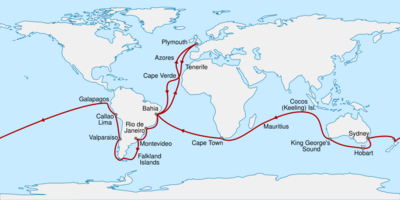

Darwin and the second voyage of HMS Beagle (1831–1836)

In December 1831 a British expedition departed under captain Robert FitzRoy, on board HMS Beagle, with the main purpose of making a hydrographic survey of the coasts of South America using calibrated chronometers and astronomical observations, producing charts for naval war or commerce. The longitude of Rio de Janeiro was to be found and also a geological survey made of a circular coral atoll in the Pacific ocean.[6]

FitzRoy thought of the advantages of having an expert in geology on board, and sought a gentleman naturalist who could be his companion. The young graduate, Charles Darwin, had hoped to see the tropics before becoming a parson, and took this opportunity. The Beagle sailed across the Atlantic Ocean then carried out detailed hydrographic surveys, returning via Tahiti and Australia , having circumnavigated the Earth. Originally planned to last two years, the expedition lasted almost five. Darwin spent most of this time exploring on land.[7] Early in the voyage he decided that he could write a book about geology, and he showed a gift for theorising. By the end of the expedition he had already made his name as a geologist and fossil collector, and the publication of his journal, known as The Voyage of the Beagle, gave him wide renown as a writer. At Punta Alta he made a major find of gigantic fossils of extinct mammals, then known from only a very few specimens. He ably collected and made detailed observations of plants and animals, with results that shook his belief that species were fixed, and provided the basis for ideas which came to him when back in England, leading to his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Alfred Russel Wallace Amazon and Malay explorations (1848–1862)

In 1848, inspired by the chronicles of earlier traveling naturalists[8] British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Bates left for Brazil with the intention of collecting insects and other animal specimens in the Amazon rainforest. Wallace charted the Rio Negro for four years, collecting specimens and making notes on peoples, geography, flora, and fauna.[9] In July 1852, while returning to the UK, the ship's cargo caught fire and all the specimens he had collected were lost.[10][11]

From 1854 to 1862, Wallace traveled again through Maritime Southeast Asia to collect specimens for sale and study nature. He collected more than 125,000 specimens, more than a thousand of them representing species new to science.[12] His observations of the marked differences across a narrow strait in the archipelago led to his proposing the zoogeographical boundary now known as the Wallace line, that divides Indonesia into two distinct parts: one with animals closely related to those of Australia, and one in which the species are largely of Asian origin. He became an expert on biogeography,[13] creating the basis for the zoogeographic regions still in use today. While he was exploring the archipelago, he refined his thoughts about evolution and had his famous insight on natural selection.

His interest resulted in his being one of the first prominent scientists to raise concerns over the environmental impact of human activity, like deforestation and invasive species. In 1878, he warned about the dangers of deforestation and soil erosion in tropical climates, like the extensive clearing of rainforest for coffee cultivation in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India .[14] Accounts of his travels were published in The Malay Archipelago in 1869, one of the most popular and influential journals of scientific exploration published during the 19th century.

Interior Africa exploration

Africa's deep interiors were not explored by Europeans until the mid to late 19th and early 20th centuries; this being due to a lack of trade potential in this region, and to serious problems with contagious tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa's case.

David Livingstone (1849–1855)

In the mid-19th century, Protestant missions were carrying on active missionary work on the Guinea coast, in South Africa and in Zanzibar. Missionaries in many instances became explorers and pioneers. David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary, had been engaged since 1840 in work north of the Orange River. In 1849, Livingstone crossed the Kalahari Desert from south to north and reached Lake Ngami. Between 1851 and 1856, he traversed the continent from west to east, discovering the great waterways of the upper Zambezi River. In November 1855, Livingstone became the first European to see the famous Victoria Falls, named after the Queen of the United Kingdom. From 1858 to 1864, the lower Zambezi, the Shire River and Lake Nyasa were explored by Livingstone. Nyasa had been first reached by the confidential slave of António da Silva Porto, a Portuguese trader established at Bié in Angola, who crossed Africa during 1853–1856 from Benguella to the mouth of the Rovuma. A prime goal for explorers was to locate the source of the River Nile. Expeditions by Burton and Speke (1857–1858) and Speke and Grant (1863) located Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria. It was eventually proved to be the latter from which the Nile flowed.

Explorers were also active in other parts of the continent. Southern Morocco, the Sahara and the Sudan were traversed in many directions between 1860 and 1875 by Georg Schweinfurth and Gustav Nachtigal.[15] These travellers not only added considerably to geographical knowledge, but obtained invaluable information concerning the people, languages and natural history of the countries in which they sojourned. Among the discoveries of Schweinfurth was one that confirmed Greek legends of the existence beyond Egypt of a "pygmy race". But the first western discoverer of the pygmies of Central Africa was Paul Du Chaillu, who found them in the Ogowe district of the west coast in 1865, five years before Schweinfurth's first meeting with them. Du Chaillu had previously, through journeys in the Gabon region between 1855 and 1859, made popular in Europe the knowledge of the existence of the gorilla, whose existence was thought to be legendary.

Henry Morton Stanley, who had in 1871 succeeded in finding and rescuing Livingstone (originating the famous line "Dr. Livingstone, I presume"), started again for Zanzibar in 1874. In one of the most memorable of all exploring expeditions in Africa, Stanley circumnavigated Victoria Nyanza and Tanganyika. Striking farther inland to the Lualaba, he followed that river down to the Atlantic Ocean—which he reached in August 1877—and proved it to be the Congo.

Serpa Pinto, Capelo, and Ivens (1877–1886)

Portuguese Serpa Pinto was the fourth explorer to cross Africa from west to east and the first to lay down a reasonably accurate route between Bié (in present-day Angola) and Lealui. In 1877, Serpa Pinto and Portuguese naval captains Capelo and Ivens explored the southern African interior starting from Benguela. Capello and Ivens turning northward whilst Serpa Pinto continued eastward. He crossed the Cuando (Kwando) river in June 1878 and in August reached Lealui, the Barotse capital on the Zambezi.

From 1884 to 1886, Hermenegildo Capelo and Roberto Ivens crossed Southern Africa between Angola and Mozambique to map the unknown territory of the Portuguese colonies. The choice of two marine officials for this achievement certainly appealed to the principles of maritime navigation. Between 1884 and 1885, Capelo and Ivens explored Africa interior, first between the coastline and Huila plain and later through the interior of Quelimane in Mozambique, continuing their hydrographic studies, updating registers, but also taking notes on the ethnographic and the linguistic characters they encountered. They established thus the so desired land route between the coasts of Angola and Mozambique, exploring vast regions of the interior located between these two territories. Their achievements were recorded in a two volume book titled: De Angola à Contra-Costa (From Angola to the Other Coast).

Exploring the Arctic and Antarctic

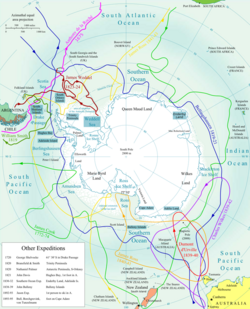

Arctic and Antarctic seas were not explored until the 19th century. Once the North Pole had been reached in 1909, several expeditions attempted to reach the South Pole. Many resulted in injury and death. The Norway Roald Amundsen finally reached the Pole in December 1911, following a dramatic race with the Englishman Robert Falcon Scott.

The Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic Ocean. Interest kindled in 1564 after Jacques Cartier's discovery of the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River, Martin Frobisher had formed a resolution to undertake the challenge of forging a trade route from England westward to India. In 1576 - 1578, he took three trips to what is now the Canadian Arctic in order to find the passage. Frobisher Bay, which he discovered, is named after him. On August 8, 1585, under the employ of Elizabeth I the English explorer John Davis entered Cumberland Sound, Baffin Island. Davis rounded Greenland before dividing his four ships into separate expeditions to search for a passage westward. Though he was unable to pass through the icy Arctic waters, he reported to his sponsors that the passage they sought is "a matter nothing doubtfull [sic],"[citation needed] and secured support for two additional expeditions, reaching as far as Hudson Bay. Though England's efforts were interrupted in 1587 because of Anglo-Spanish War, Davis's favorable reports on the region and its people would inspire explorers in the coming century.[citation needed]

In the first half of the 19th century, parts of the Northwest Passage were explored separately by a number of different expeditions, including those by John Ross, William Edward Parry, James Clark Ross; and overland expeditions led by John Franklin, George Back, Peter Warren Dease, Thomas Simpson, and John Rae. Sir Robert McClure was credited with the discovery of the Northwest Passage by sea in 1851[16] when he looked across McClure Strait from Banks Island and viewed Melville Island. However, the strait was blocked by young ice at this point in the season, and not navigable to ships.[17] The only usable route, linking the entrances of Lancaster Sound and Dolphin and Union Strait was first used by John Rae in 1851. Rae used a pragmatic approach of traveling by land on foot and dogsled, and typically employed less than ten people in his exploration parties.[18]

The Northwest Passage was not completely conquered by sea until 1906, when the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who had sailed just in time to escape creditors seeking to stop the expedition, completed a three-year voyage in the converted 47-ton herring boat Gjøa. At the end of this trip, he walked into the city of Eagle, Alaska, and sent a telegram announcing his success. His route was not commercially practical; in addition to the time taken, some of the waterways were extremely shallow.[19]

The North Pole (1909–1952)

While the South Pole lies on a continental land mass, the North Pole is located in the middle of the Arctic Ocean amidst waters that are almost permanently covered with constantly shifting sea ice.

A number of expeditions set out with the intention of reaching the North Pole but did not succeed; that of British naval officer William Edward Parry, in 1827, the American Polaris expedition in 1871, and Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen in 1895. American Frederick Albert Cook claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1908, but this has not been widely accepted.[citation needed]

The conquest of the North Pole was for many years credited to American Navy engineer Robert Peary, who claimed to have reached the Pole on April 6, 1909,[16] accompanied by American Matthew Henson and four Inuit men named Ootah, Seeglo, Egingwah, and Ooqueah. However, Peary's claim remains controversial.[20][21] The party that accompanied Peary on the final stage of the journey included no one who was trained in navigation and could independently confirm his own navigational work, which some claim to have been particularly sloppy as he approached the Pole. He traveled with the aid of dogsleds and three separate support crews who turned back at successive intervals before reaching the Pole. Many modern explorers, contend that Peary could not have reached the pole on foot in the time he claimed.

The first undisputed sighting of the Pole was on May 12, 1926 by Norway explorer Roald Amundsen and his United States sponsor Lincoln Ellsworth from the airship Norge. Norge, though Norwegian owned, was designed and piloted by the Italian Umberto Nobile. The flight started from Svalbard and crossed the icecap to Alaska. Nobile, along with several scientists and crew from the Norge, overflew the Pole a second time on May 24, 1928 in the airship Italia. The Italia crashed on its return from the Pole, with the loss of half the crew.

United States Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Joseph O. Fletcher and Lieutenant William P. Benedict finally landed a plane at the Pole on May 3, 1952, accompanied by the scientist Albert P. Crary.

Antarctica exploration

Early Western theories believed that in the far south of the globe existed a vast continent, known as Terra Australis. The rounding of the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn in the 15th and 16th centuries proved that Terra Australis Incognita ("Unknown Southern Land"), if it existed, was a continent in its own right. The basic geography of the Antarctic coastline was not understood until the mid-to-late 19th century.

It may safely be said that all the navigators who fell in with the southern ice up to 1750 did so by being driven off their course and not of set purpose. An exception may perhaps be made in favor of Edmond Halley's voyage in HMS Paramour for magnetic investigations in the South Atlantic when he met the ice in 52° S in January 1700, but that latitude was his farthest south. A determined effort on the part of the French naval officer Pierre Bouvet to discover the South Land described by a half legendary sieur de Gonneville resulted only in the discovery of Bouvet Island in 54°10′ S, and in the navigation of 48° of longitude of ice-cumbered sea nearly in 55° S in 1739. In 1771, Yves Joseph Kerguelen sailed from France with instructions to proceed south from Mauritius in search of "a very large continent". He lighted upon a land in 50° S which he called South France, and believed to be the central mass of the southern continent. He was sent out again to complete the exploration of the new land, and found it to be only an inhospitable island which he renamed in disgust the Isle of Desolation, but in which posterity has recognized his courageous efforts by naming it Kerguelen Land.[22]

The obsession of the undiscovered continent culminated in the brain of Alexander Dalrymple, a hydrographer who was nominated by the Royal Society to command the Transit of Venus expedition to Tahiti in 1769. The command of the expedition was given by the admiralty to Captain James Cook. Sailing in 1772 with the Resolution and the Adventure under Captain Tobias Furneaux, Cook first searched in vain for Bouvet Island, then sailed for 20 degrees of longitude to the westward in latitude 58° S, and then 30° eastward for the most part south of 60° S, a higher southern latitude than had ever been voluntarily entered before by any vessel. On 17 January 1773 the Antarctic Circle was crossed for the first time in history and the two ships reached [ ⚑ ] Unknown format in {{Coord}}. Parameters:

- 1=67

- 2=15

- 3=S

- 4=39

- 5=35

- 6=E

- 7=

- 8=

- 9=, where their course was stopped by ice.[22]

The first land south of the parallel 60° south latitude was discovered by the Englishman William Smith, who sighted Livingston Island on 19 February 1819.

In 1820, several expeditions claimed to have been the first to have sighted Antarctica. The first confirmed sighting of mainland Antarctica cannot be accurately attributed to one single person. It can, however, be narrowed down to three individuals. According to various sources,[23][24][25] three men all sighted Antarctica within days or months of each other: Fabian von Bellingshausen, a captain in the Russian Imperial Navy; Edward Bransfield, a captain in the British navy; and Nathaniel Palmer, an American sealer out of Stonington, Connecticut. It is certain that on 28 January 1820 (New Style), the expedition led by Fabian von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev on two ships reached a point within 20 miles (40 km) of the Antarctic mainland and saw ice-fields there. On 30 January 1820, Bransfield sighted Trinity Peninsula, the northernmost point of the Antarctic mainland, while Palmer sighted the mainland in the area south of Trinity Peninsula in November 1820. Bellingshausen's expedition also discovered Peter I Island and Alexander I Island, the first islands to be discovered south of the circle.

Only slightly more than a year later, the first landing on the Antarctic mainland was arguably by the American Captain John Davis, a sealer, who claimed to have set foot there on 7 February 1821, though this is not accepted by all historians.[26][failed verification]

The South Pole (1911)

After the North Magnetic Pole was located in 1831, explorers and scientists began looking for the South Magnetic Pole. James Clark Ross, a British naval officer, identified its approximate location, but was unable to reach it on his trip in 1841. Commanding the British ships Erebus and Terror, he braved the pack ice and approached what is now known as the Ross Ice Shelf, a massive floating ice shelf over 100 feet (30 m) high. His expedition sailed eastward along the southern Antarctic coast discovering mountains which were since named after his ships: Mount Erebus, the most active volcano on Antarctica, and Mount Terror.

Once the North Pole had been reached in 1909, several expeditions attempted to reach the South Pole. Many resulted in injury and death. The Norway Roald Amundsen reached the Pole in December 1911, following a race with the Englishman Robert Falcon Scott.

The first attempt to find a route to the South Pole was made by British explorer Robert Falcon Scott on the Discovery Expedition of 1901–04. Scott, accompanied by Ernest Shackleton and Edward Wilson, set out with the aim of traveling as far south as possible, and on 31 December 1902, reached 82°16′ S.[27] Shackleton later returned to Antarctica as leader of the Nimrod Expedition in a bid to reach the Pole. On 9 January 1909, with three companions, he reached 88°23′ S – 112 statute miles from the Pole – before being forced to turn back.[28]

The first humans to reach the South Pole were Norway Roald Amundsen and his party on December 14, 1911. Amundsen named his camp Polheim and the entire plateau surrounding the Pole King Haakon VII Vidde in honour of King Haakon VII of Norway. Robert Falcon Scott had also returned to Antarctica with his second expedition, the Terra Nova Expedition, in a race against Amundsen to the Pole. Scott and four other men reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912, thirty-four days after Amundsen. On the return trip, Scott and his four companions all died of starvation and extreme cold.

In 1914 Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition set out with the goal of crossing Antarctica via the South Pole, but his ship, the Endurance, was frozen in pack-ice and sank 11 months later. The overland journey was never made.

See also

- Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World

- United States Exploring Expedition (1838 to 1842)

- Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest

References

- ↑ Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911). "Cook, James". in Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–72.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 per Collingridge (2002)[full citation needed]

- ↑ per Horwitz (2003)[full citation needed]

- ↑ Sykes, Bryan (2001). The Seven Daughters of Eve. Norton Publishing: New York City, NY and London, England. ISBN 0-393-02018-5.

- ↑ Wulf, Andrea (2016). The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 120–133.

- ↑ Love, Ronald (2006). Maritime Exploration in the Age of Discovery, 1415-1800. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 65–72. ISBN 9780313320439. https://archive.org/details/maritimeexplorat00love_801.

- ↑ Browne, E. Janet; Neve, Michael (1989), "Introduction", in Darwin, Charles, Voyage of the Beagle: Charles Darwin's Journal of researches, London: Penguin Books, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-14-043268-8

- ↑ Slotten The Heretic in Darwin's Court pp. 34–37.

- ↑ Raby Bright Paradise pp. 89–95.

- ↑ Wilson pp. 42–43.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Slotten pp. 87-88[full citation needed]

- ↑ Shermer In Darwin's Shadow pp. 14.

- ↑ Smith, Charles H.. "Alfred Russel Wallace: Evolution of an Evolutionist Introduction". The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University. http://www.wku.edu/~smithch/wallace/chsarwin.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ Slotten pp. 352–353.[full citation needed]

- ↑ "Sahara and Sudan: The Results of Six Years Travel in Africa". 1879–1889. http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7312/. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "ARCTIC EXPLORATION - CHRONOLOGY". Quark Expeditions. 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20081120062816/http://www.quarkexpeditions.com/arctic/exploration.shtml. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ↑ Burton, p. 219.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Richards, R. L. (2000). "John Rae". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=6386. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- ↑ "Northwest Passage". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-01-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20070102171805/http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0005816. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- ↑ "ARCTIC, THE". Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press. 2004. https://www.questia.com/library/encyclopedia/arctic_the.jsp. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ↑ "North Pole". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2006. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/north-pole/. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mill, Hugh Robert (1911). "Polar Regions". in Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 961–962.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mill, Hugh Robert (1911). "Polar Regions". in Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 961–962.

- ↑ U.S. Antarctic Program External Panel. "Antarctica —past and present". NSF. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/1997/antpanel/antpan05.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Guthridge, Guy G.. "Nathaniel Brown Palmer". NASA. Archived from the original on 2006-02-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20060202101525/http://quest.arc.nasa.gov/antarctica/background/NSF/palmer.html. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ↑ "AARC Palmer Station Info". Archived from the original on 2006-08-28. https://web.archive.org/web/20060828065910/http://arcane.ucsd.edu/pstat.html. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

- ↑ Headland, R.K.. "Summary of the Peri-Antarctic Islands". Scott Polar Research Institute. http://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/resources/infosheets/19.html. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ↑ Science into Policy: Global Lessons from Antarctica, p. 37, Paul Arthur Berkman, 2002

- ↑ Antarctica, p. 24, Paul Simpson-Housley, 1992

{{Navbox | name = Geography topics | state = collapsed | title = Geography topics | bodyclass = hlist

| above =

| group1 = Branches | list1 =

{{Navbox|child

| bodyclass = hlist

| group1 = Human | list1 =

- Agricultural

- Behavioral

- Cultural

- Development

- Economic

- Health

- Historical

- Political

- Population

- Settlement

| group2 = Physical | list2 =

- Biogeography

- Coastal / Oceanography

- Earth science

- Earth system science

- Geomorphology / Geology

- Glaciology

- [[Earth:HydrologHydrology / Limnology

- Pedology (Edaphology/Soil science)

- Quaternary science

| group3 = Integrated | list3 =

}}

| group2 = Techniques and tools | list2 =

| group3 = Institutions | list3 =

- Geographic data and information organizations

- Geographical societies

- Geoscience societies

- National mapping agency

| group4 = Education | list4 =

| below =

}}

|