Software:Legend (1992 video game)

| Legend | |

|---|---|

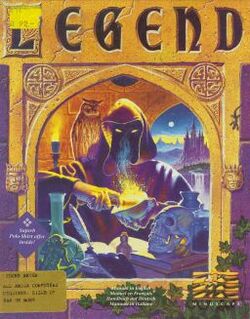

European Amiga cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Mindscape |

| Publisher(s) | The Software Toolworks |

| Director(s) | Mike Simpson[1] |

| Programmer(s) | Anthony Taglione[1] |

| Artist(s) | Pete James[1] |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Atari ST, DOS |

| Release | September 1992 |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Legend, also known as The Four Crystals of Trazere in the United States, is an isometric fantasy role-playing game released in 1992 for the Amiga, Atari ST, and DOS. It was developed by Pete James and Anthony Taglione for the then UK-based Mindscape, and published by The Software Toolworks. In the game, the player controls four adventurers on a quest to save the land of Trazere from an ancient, re-awakening evil. In 1993, Mindscape released a sequel, Worlds of Legend. The copyrights for both "Legend" and "Worlds of Legend" are currently owned by Ubisoft, who bought them from Mattel Interactive with the rest of the Mindscape library in 2001.

Release

The Four Crystals of Trazere is an American version of Legend. It was commenced under funding from Mirrorsoft, which went into receivership after the death of Robert Maxwell. The following day, December 11, Taglione was meeting with Phil Harrison of Mindscape to discuss the conversion to PC of Tony Crowther's Amiga game, Captive. On hearing that Mirrorsoft had just gone into receivership, Taglione suggested the possibility of publication by Mindscape. The game was released by Mindscape in 1992.

PC Home demo

In October 1992, an exclusive, specially-written demo version of Legend, courtesy of Anthony 'Tag' Taglione and Mindscape, was released free in the UK with the first issue of the personal computer magazine PC Home, as part of a real-life competition by Mindscape. The demo's content is not taken from the storyline or any part of the full game, but comprises a small but challenging standalone adventure in the world of Trazere.

The gameplay of the demo is limited to the city of Treihadwyl, and a single dungeon within - the overrun cellars of the Mad Monks' temple - as there is no world map view and therefore no way to travel to any other location. However, the adventure has not been subsequently re-released or incorporated into any retail version of the game, and as such its availability is incredibly limited.

The demo's difficulty is high in comparison to the beginning stages of the full game, due to the presence of far more intricate puzzle rooms, stronger monster spawns, and more frequent wandering monster ambushes. However, these challenges are offset slightly in that the runemaster begins the demo with an array of powerful spells ready-made, invaluable protective and healing items are scattered around the first dungeon room, and mid to high-level weapons and armour are always available for purchase from the city blacksmith.

The following year, Taglione coded another similarly unique demo for PC Home, this time for Legend's sequel, Worlds of Legend: Son of the Empire.

Sequel

The game spawned a sequel a year later called Worlds of Legend.[2] Although set in a different realm of Trazere, the gameplay is almost identical with a few tweaks and bugfixes.

Development

Legend began development in August 1990, and was originally scheduled for a September 1991 release for Amiga, Atari ST, and DOS.[1] In an April 1991 issue of British gaming magazine The One, The One interviewed Anthony Taglione, Legend's programmer, for information regarding its development in a pre-release interview.[1] This interview was conducted when Legend was to be published by Mirrorsoft,[1] and prior to Robert Maxwell's death and subsequent bankruptcy of Mirrorsoft; this possibly contributed to Legend's delayed release. The team behind Legend had previously worked together on Bloodwych, and worked on Legend long-distance.[1] Legend's development team corresponded though the internet, and met in-person intermittently.[1] Legend was heavily inspired by Dungeons & Dragons, and Taglione expressed that "We wanted very much to produce an environment which simulated playing tabletop D&D with characters running around and fighting each other ... The essential environment is still puzzles and D&D, but it's becoming much more like an arcade game [due to its combat]."[1] Legend was first conceived as a sequel to Bloodwych, and was to utilize turn-based gameplay as opposed to realtime gameplay, as in the final game.[1] Legend uses pathfinding and AI for monsters & characters, allowing them to fight without user intervention.[1] This is particularly necessary due to Legend's real-time combat and the ability to control four characters; Taglione expresses in regards to this that "It's a question of maintaining a very fine balance between having the [game play] itself and giving the player as much control as he or she's going to want."[1]

'Flexibility' in regards to differing playstyles was a priority in Legend's development, and Legend's magic system was initially based upon that of Bloodwych.[1] Taglione and graphic artist Pete James initially drafted Legend's magic system, and Taglione expressed that "Initially we were going to base it on a Bloodwych type system, but then we thought 'well, we've done that, what's the point?' ... then I thought of this idea of having a completely general spell system."[1] Legend allows the creation of custom spells using runes and ingredients, allowing the combination of various effects, e.g. a spell could heal the player while simultaneously attack a monster.[1] Taglione states that this was implemented to encourage players to experiment, expressing that "The idea is that people will create their own individual spell books. Literally hundreds and thousands of different spells are available in the system just from these 16 basic runes."[1] Whether the player should be able to access the spell-creation menu during combat was "a matter of heated debate" in Legend's development.[1] Legend has a sprite limit of 'around 200' sprites on-screen at once.[1]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

The Four Crystals of Trazere was reviewed in 1992 in Dragon #187 by Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser in "The Role of Computers" column. The reviewers gave the DOS version 3 out of 5 stars.[4] The One gave the Amiga version of Legend an overall score of 79%, praising its gameplay and pacing of quests, stating that "[Legend] presents a realistic, attainable challenge, with plenty of sub-games to keep the action moving along ... Thanks to some thoughtful game design, however, even a novice Role Player will, at the very least, understand what is loosely expected of him." The One notes the magic and potion-making system, saying it "deserves a special mention for its entertainment value. Absolutely fiendish potions can be mixed ... and used with great effect in the most unlikely situations."[3]

Legend was named the 80th best computer game ever by PC Gamer UK in 1997. The editors called it a precursor to Diablo, and wrote that it offered "countless nights of puzzling, hacking, slashing and magic-casting."[5]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Hamza, Kati (April 1991). "Spelling It Out". The One (emap Images) (31): 32–33. https://archive.org/details/theone-magazine-31/page/n31/mode/2up.

- ↑ "Worlds of Legend: Son of the Empire for Amiga (1993)". https://www.mobygames.com/game/amiga/worlds-of-legend-son-of-the-empire.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Legend Review". The One (emap Images) (45): 46. June 1992. https://archive.org/details/theone-magazine-45/page/n45.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (November 1992). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (187): 59–64. https://archive.org/stream/DragonMagazine260_201801/DragonMagazine187#page/n61/mode/2up.

- ↑ Flynn, James; Owen, Steve; Pierce, Matthew; Davis, Jonathan; Longhurst, Richard (July 1997). "The PC Gamer Top 100". PC Gamer UK (45): 51–83.

External links

- The Four Crystals of Trazere at MobyGames

- The Four Crystals of Trazere can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

|