Biology:Steller's jay

| Steller's jay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Steller's jay in Flagstaff, Arizona, with white head-markings typical of eastern-variety birds (C. s. macrolopha) | |

| File:Cyanocitta stelleri - Steller's Jay - XC109654.ogg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Cyanocitta |

| Species: | C. stelleri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cyanocitta stelleri (Gmelin, JF, 1788)

| |

| |

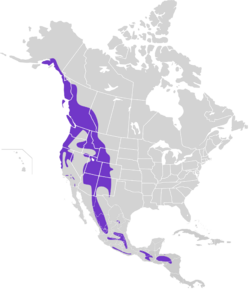

Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) is a bird native to western North America and the mountains of Central America, closely related to the blue jay (C. cristata) found in eastern North America. It is the only crested jay west of the Rocky Mountains. It is also sometimes colloquially called a "blue jay" in the Pacific Northwest, but is distinct from the blue jay of eastern North America. The species inhabits pine-oak and coniferous forests.

Taxonomy

Steller's jay was formally described in 1788 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with the crows in the genus Corvus and coined the binomial name Corvus stelleri.[2] Gmelin based his account on "Stellers crow" that had been described in 1781 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his book A General Synopsis of Birds. Latham had examined a specimen belonging to the naturalist Joseph Banks that had been collected in Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island off the Pacific coast of Canada.[3] The specimen was one of the birds collected on Captain James Cook's third voyage to the Pacific Ocean. During this voyage Cook visited Nootka Sound from 29 March until 26 Apr 1778.[4] Steller's jay is now placed with the blue jay in the genus Cyanocitta that was introduced in 1845 by the English ornithologist Hugh Strickland.[5]

The bird is named after the Germany naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, the first European to record them, in 1741.[6][7]

Thirteen subspecies are recognised:[5]

- C. s. stelleri (Gmelin, JF, 1788) – south Alaska and coastal west Canada to northwest Oregon (northwest USA)

- C. s. carlottae Osgood, 1901 – Haida Gwaii (off west Canada)

- C. s. frontalis (Ridgway, 1873) – central Oregon, east California to central west Nevada (west USA)

- C. s. carbonacea Grinnell, 1900 – coastal central west California (west USA)

- C. s. annectens (Baird, SF, 1874) – central British Columbia to southeast Alberta (southwest Canada) south to northeast Oregon and northwest Wyoming (northwest USA)

- C. s. macrolopha Baird, SF, 1854 – east Nevada to southwest South Dakota (central west USA) south to north Mexico

- C. s. diademata (Bonaparte, 1850) – northwest Mexico

- C. s. phillipsi Browning, 1993 – mainly San Luis Potosí (central Mexico)

- C. s. azteca Ridgway, 1899 – central south Mexico

- C. s. coronata (Swainson, 1827) – southwest, central east, south Mexico and west Guatemala

- C. s. purpurea Aldrich, 1944 – Michoacán (southwest Mexico)

- C. s. restricta Phillips, AR, 1966 – Oaxaca (south Mexico)

- C. s. suavis Miller, W & Griscom, 1925 – Nicaragua and Honduras

Description

Steller's jay is about 30–34 cm (12–13 in) long and weighs about 100–140 g (3.5–4.9 oz). Steller's jay shows a great deal of regional variation throughout its range. Blackish-brown-headed birds from the north gradually become bluer-headed farther south.[8] Steller's jay has a more slender bill and longer legs than the blue jay and, in northern populations, has a much more pronounced crest.[9]:69[10] It is also somewhat larger.

The head is blackish-brown, black, or dark blue, depending on the subspecies of the bird, with lighter streaks on the forehead. This dark coloring gives way from the shoulders and lower breast to silvery blue. The primaries and tail are a rich blue with darker barring. Birds in the eastern part of its range along the Great Divide have white markings on the head, especially over the eyes; birds further west have light blue markers and birds in the far west along the Pacific Coast have small, very faint, or no white or light markings at all.

Phylogeny

Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) is one of two species in the genus Cyanocitta, the other species being the blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata); because the two species sometimes interbreed naturally where their ranges overlap in the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains, their status as distinct species has been contested. There are 18 subspecies of Steller's jays ranging from Alaska to Nicaragua, with nine found north of Mexico, often with areas of low or non-existent presence of the species separating the subspecies. At least some of the variation in the species is due to different degrees of hybridization between Steller's jays (C. stelleri) and blue jays (C. cristata).[11]

The genus Cyanocitta is part of the passerine family Corvidae, which consists of the crows, ravens, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs, and nutcrackers.

Habitat

Steller's jay occurs in most of the forested areas of western North America as far east as the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains from southern Alaska in the north to northern Nicaragua in the south[11] completely replacing the blue jay prevalent on the rest of the continent in those areas. Its density is lower in the central Rocky Mountain region (Montana, Idaho, Wyoming and eastern Utah) plus the desert or scrubland areas of the Great Basin (e.g. Nevada, western Utah, southern Arizona and parts of California). Some hybridization with the blue jay in eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains, especially Colorado, has been reported. It is also found in Mexico occurring through the interior highlands in northwestern Mexico as well as patchy populations in the rest of Mexico. In the northern end of its range it appears to be spreading from coastal Southeast Alaska across the Coast Mountains into southern Yukon Territory.[12]

Steller's jay is also found in Mexico's interior highlands from Chihuahua and Sonora in the northwest southward to Jalisco, as well as other patchy populations found throughout Mexico. It is also found in south-central Guatemala, northern El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua.[8]

Although Steller's jay primarily lives in coniferous forests, it can be found in other types of forests as well. They can be found from low to moderate elevations, and on rare occasions to as high as the tree line. Steller's jays are common in residential and agricultural areas with nearby forests.[13]

Diet

Steller's jays are omnivores; their diet is about two-thirds plant matter and one-third animal matter. They gather food both from the ground and from trees. Steller's jay's diet includes a wide range of seeds, nuts, berries and other fruit. They also eat many types of invertebrates, small rodents, eggs, and nestlings such as those of the marbled murrelet. There are some accounts of them eating small reptiles, both snakes and lizards.[13]

Acorns and conifer seeds are staples during the non-breeding season; these are often cached in the ground or in trees for later consumption. They exploit human-provided food sources, frequently scavenging picnics and campsites, where it competes with the Canada jay.

Steller's jays will visit feeders and prefer black-oil sunflower seeds, white striped sunflower seeds, cracked corn, shelled raw peanuts, and are especially attracted to whole raw peanuts. Suet is also consumed but mostly in the winter season.

Breeding

Steller's jays breed in monogamous pairs.[14] The clutch is usually incubated entirely by the female for about 16 days.[15] The male feeds the female during this time. Though they are known to be loud both day and night, during nesting they are quiet in order to not attract attention.[16]

The nest is usually in a conifer, but is sometimes built in a hollow in a tree or beneath the awning of a house or other structure. Similar in construction to the blue jay's nest, it tends to be a bit larger (25 to 43 cm (9.8 to 16.9 in)), using a number of natural materials or scavenged trash, often mixed with mud. Between two and six eggs are laid during breeding season. The eggs are oval in shape with a somewhat glossy surface. The background colour of the egg shell tends to be pale variations of greenish-blue with brown- or olive-coloured speckles.

Vocalizations

Like other jays, Steller's jay has numerous and variable vocalizations. One common call is a harsh "SHACK-Sheck-sheck-sheck-sheck-sheck" series; another "skreeka! skreeka!" call sounds almost exactly like an old-fashioned pump handle; yet another is a soft, breathy "hoodle hoodle" whistle. Its alarm call is a harsh, nasal "wah". Some calls are sex-specific: females produce a rattling sound, while males make a high-pitched "gleep gleep".

Steller's jay is also a noted mimic: it can imitate the vocalizations of many species of birds, other animals, and sounds of non-animal origin. It often will imitate the calls from birds of prey such as the red-tailed hawk, red-shouldered hawk, and osprey as a warning of danger to others or territorial behavior, causing other birds to seek cover and flee feeding areas.[11][13]

Steller's jays have the ability to assess risk using different predator detection cues. They have many alarm calls that are dependent on their interaction between predator identity and cue type. Steller's jays respond to sharp-shinned hawks with a longer latency to return to feeding whether they are both seen or heard. In contrast to Steller's jays, sharp-shinned hawks responded to northern goshawks with a longer latency to resume feeding if they were seen in comparison to only heard. The difference in reactions suggest that this is a distinct risk of assessment being conducted by Steller's jays. Steller's jays will then vary the production of their "wah", "wek", and mimic red-tailed hawk calls in response to different detection cues.[17]

Provincial bird

Steller's jay is the provincial bird of the Canadian province of British Columbia.[18]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2017). "Cyanocitta stelleri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22705614A118809071. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22705614A118809071.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22705614/118809071. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1788) (in Latin). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1, Part 1 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 370. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2896970.

- ↑ Latham, John (1781). A General Synopsis of Birds. 1, Part 1. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. pp. 387–388 No. 21. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/33727919.

- ↑ Stresemann, Erwin (1949). "Birds collected in the north Pacific area during Capt. James Cook's last voyage (1778 and 1779)". Ibis 91 (2): 244–255 [248]. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1949.tb02264.x.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds (January 2023). "Crows, mudnesters, birds-of-paradise". IOC World Bird List Version 13.1. International Ornithologists' Union. https://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/crows/.

- ↑ "Steller's Jay". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell University. 2013. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/343/articles/introduction.

- ↑ Evans, Howard Ensign (1986). Halpern, Daniel. ed. Antæus on Nature. London, UK: Collins Harvill. p. 24.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Walker, L. E.; Pyle, P.; Patten, M. A.; Green, E.; Davison, W.; Muehter, V. R. (2016). Rodewald, P. G.. ed. "Steller's Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri)" (in en). The Birds of North America Online (Ithaca, New York: Cornell Lab of Ornithology). doi:10.2173/bna.343. https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/stejay/introduction. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- ↑ Madge, S.; Burn, H. (1994). Crows and Jays: A Guide to the Crows, Jays and Magpies of the World. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Walker, L. E.; Pyle, P.; Patten, M. A.; Greene, E.; Davison, W.; Muehter, V. R. (2020). "Steller's Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri), version 1.0". Birds of the World. doi:10.2173/bow.stejay.01.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Steller's Jay Cyanocitta stelleri". National Geographic. 4 May 2010. http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birding/stellers-jay/.

- ↑ Ritchie, Haley (2020-10-27). "Steller's jay invasion: Coastal species making a rare appearance in southern Yukon". Yukon News. https://www.yukon-news.com/news/stellers-jay-invasion-coastal-species-making-a-rare-appearance-in-southern-yukon/.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Steller's Jay". Seattle Audubon Society. http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/stellers_jay.

- ↑ Gabriel, P. O.; Black, J. M. (July 2012). "Reproduction in Steller's Jays (Cyanocitta stelleri): individual characteristics and behavioral strategies". The Auk 129 (3): 377–386. doi:10.1525/auk.2012.11234.

- ↑ Tweit, R. C. (2005). "Steller's Jay". Texas A&M. http://txtbba.tamu.edu/species-accounts/stellers-jay/.

- ↑ Kaufman, K. (13 November 2014). "Steller's Jay". https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/stellers-jay.

- ↑ Billings, Alexis (May–June 2017). "Steller's jays assess and communicate about predator risk using detection cues and identity". https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/28/3/776/3069041.

- ↑ "B.C. Symbols - Province of British Columbia". Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/celebrating-british-columbia/symbols-of-bc.

Further reading

- Goodwin, D. (1976). Crows of the World. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Greene, E.; Davison, W.; Davison, W.; Muehter, V.R. (1998). The Birds of North America. No. 343.

External links

- "Steller's jay". Cornell University. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Stellers_Jay/.

- "Steller's jay media". Internet Bird Collection. http://www.hbw.com/ibc/species/stellers-jay-cyanocitta-stelleri.

- Steller's jay photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

Wikidata ☰ Q838749 entry

|