Biology:Phorcys dubei

| Phorcys | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Gorgonopsia |

| Genus: | †Phorcys Kammerer & Rubidge, 2022 |

| Species: | †P. dubei

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Phorcys dubei Kammerer & Rubidge, 2022

| |

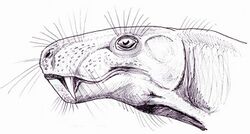

Phorcys is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian (predatory therapsids, related to modern mammals) that lived during the Middle Permian period (Guadalupian) of what is now South Africa . It is known from two specimens, both portions from the back of the skull, that were described and named in 2022 as a new genus and species P. dubei by Christian Kammerer and Bruce Rubidge. The generic name is from Phorcys of Greek mythology, the father of the Gorgons from which the gorgonopsians are named after, and refers to its status as one of the oldest representatives of the group in the fossil record. Phorcys was recovered from the lowest strata of the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone (AZ) of the Beaufort Group, making it one of the oldest known gorgonopsians in the fossil record—second only to fragmentary remains of an indeterminate gorgonopsian from the older underlying Eodicynodon Assemblage Zone.

Phorcys was also unexpectedly large for an early gorgonopsian with a total skull length estimated at ~30 cm (12 in), comparable to in size to later gorgonopsians and notably larger than the similarly aged Eriphostoma with skull lengths of only ~10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in). This contradicts prior suggestions that gorgonopsians only achieved larger sizes, and associated top predator status, following the extinction of dinocephalians and large therocephalian therapsids in the Late Permian. Indeed, Phorcys was comparable in size to a contemporary specimen of a scylacosaurid therocephalian with a skull estimated to be ~21 centimetres (8.3 in) long, and even to the slightly older anteosaur Australosyodon (skull length ~26 cm (10 in)). Phorcys and other gorgonopsians may then have been top predators in some Middle Permian assemblages.

Discovery and naming

Only two specimens of Phorcys are known, each consisting of weathered partial skulls broken off before the snout. Both specimens were collected from a locality near Delportsrivier, a farm in Jansenville of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, and are catalogued as BP/1/5850 and BP/1/5851 by the Evolutionary Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand, where they are stored. These specimens were initially reported on in 1995 by palaeontologist Bruce S. Rubidge,[1] however they would not be described and named as a new genus and species, Phorcys dubei, until 2022 by Rubidge and fellow palaeontologist Christian F. Kammerer.[2] The two specimens were prepared by Mr. Charlton Dube (who himself collected BP/1/5850), and the specific name dubei honours his contribution and commends his skills at fossil preparation. The generic name Phorcys is after Phorcys of ancient Greek mythology, a primordial god and the father of the Gorgons. The name alludes to its status as one of the earliest known gorgonopsians, the group itself being named after the mythological Gorgons with many genera including "gorgon" in their own names.[2]

Although both specimens are weathered and damaged, BP/1/5851 is considerably more complete and so was designated the holotype specimen by Kammerer and Rubidge. It preserves most of the skull from the occiput (the back face of the skull) up to the orbits, including the basicranium (the floor of the skull beneath the braincase), an eroded upper surface preserving the intact preparietal and portions of the surrounding frontals and parietal bones, with a broken left zygomatic arch and a left palatine displaced into the left orbit, the only known bone from the front half of the skull. The paratype is less complete and more badly weathered, consisting mostly of a partial occiput with associated parts of the skull roof and the basicranium (as well as other unidentified bone fragments).[2]

The locality where both specimens were recovered belongs to the eastern exposures of the Abrahamskraal Formation (of which historically were labelled the Koonap Formation), the lowest (and so oldest) geological formation in the fossiliferous Permo-Triassic aged Beaufort Group of the Karoo Basin. The layers of the Abrahamskraal Formation near Jansenville are typically correlated to the lower Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone (AZ) fauna.[3] However, due to the unique faunal assemblage known from these localities that are seemingly absent from the rest of the Tapinocephalus AZ (including Phorcys), it has been suggested they may represent a distinct faunal assemblage between the younger Tapinocephalus AZ and the older underlying Eodicynodon Assemblage Zone.[4] This biostratigraphic position corresponds to a Middle Permian (or Guadalupian) age, dating to somewhere within the Wordian to Capitanian stages. Phorcys then represents one of the oldest known gorgonopsians worldwide, and certainly the oldest named species. Only one other specimen is older, having been discovered in the underlying Eodicynodon AZ. This specimen, NMQR 2982, was also described by Kammerer and Rubidge in the same article as Phorcys. However, the specimen only consists of a pair of jaw tips and lacks any characteristics diagnosable to the genus or species level, and so Kammerer and Rubidge referred NMQR 2982 to Gorgonopsia indet (although they acknowledged the possibility it may be conspecific with Phorcys, lack of overlapping material makes this impossible to determine).[2]

Description

Little can be said for the overall anatomy of Phorcys as it is only known from partial skulls missing everything in front of the eyes. Nonetheless, it is estimated to be a relatively large-bodied gorgonopsian with a complete skull length estimated at 30 cm (12 in), assuming it had similar proportions to the related Gorgonops. For comparison, the largest Late Permian gorgonopsians such as Inostrancevia and Rubidgea reached skull lengths in excess of 40 cm (16 in).[5] Collectively, the preserved portions of Phorcys make up the rear of the skull behind the eyes, including the postorbital bar, zygomatic arch, the occiput, and much of the basicranium. Only one bone from the front of the skull is known, the palatine, which bears numerous palatal teeth. Although incomplete and eroded, Phorcys preserves various characteristics that mark it as a gorgonopsian from other groups of therapsids.

One such feature is the width of the postorbital bar behind the eyes, which increases in its front-to-back width from the roof of the skull down to where it meets the jugal on the zygomatic arch, more than doubling its width from 2.2 cm to 4.5 cm. Such an extreme expansion is unique to gorgonopsians, as is its convex border of the temporal fenestra, which in other predatory therapsids is often concave to undercut the orbit. Although the roof of the skull has been narrowed by erosion, the area between the two temporal fenestra (the intratemporal region) is inferred to have been broad and flat like other gorgonopsians from a broken edge still attached to the back of the postorbital, revealing its true extent. Phorcys also had a large preparietal (a bone unique to just a few therapsid groups, including gorgonopsians) with a rounded front edge in the characteristic shape for gorgonopsians. The occiput is broad and low, wider than it is tall as typical of gorgonopsians, and has a vertical face. This contrasts with the only other gorgonopsian from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone, Eriphostoma, which consistently preserves an occiput that slopes up and forwards. Like other gorgonopsians, the occiput has a sulcus (or furrow) in the squamosal bone on either side, mostly exposed on the back but curving around partially onto the side of the zygomatic arch. The occiput also sports a prominent nuchal crest running vertically down the centre and widening from the skull roof down to the circular foramen magnum (the opening for the spinal cord, bordered by the occipital condyle beneath). This crest is common in gorgonopsians and served for muscle attachment, but it is especially robust in Phorcys for its body size.[2]

The basioccipital, a bone in the basicranium that forms the bottom rim of the foramen magnum and extends below to form the floor of the back of the braincase, distinguishes Phorcys from all other known gorgonopsians. It sports a pair of knob-like protuberances at the back and inner margins of the "basal tubera", ovoid projections of bone that run from the basiccopital and inwards on to the fused parabasisphenoid in front. These protuberances are unknown in any other gorgonopsian, and are present in both specimens. The parabasisphenoid itself is typical of gorgonopsians, sporting the characteristic tall, thin, vertical blade of bone on the narrow cultriform process that extends forwards down the middle of the palate. The epipterygoid, an elongated strap-like process of bone, rise up from either side of the basicranium to where they would contact the parietal bones above, as is the typical form for therapsids.[2]

The only bone from the front half of the skull known is the palatine from the roof of the mouth. Like other gorgonopsians, the palatine sports a prominent bony boss with palatal teeth. In Phorcys, the palatal teeth are arranged in a delta-shaped row on the boss, resembling a forward-pointing arrowhead or inverted 'V', consisting of 10 teeth. This delta-shaped tooth row is uncommon among gorgonopsians, but is found in other early genera such Gorgonops and Eriphostoma.[6] The 10th palatal tooth (at the rear of the lateral margin) is conspicuously larger than the rest of the palatal teeth (0.5 cm vs 0.2-0.3 cm), although this was interpreted as an individually unique variation in tooth replacement, as the palatal teeth of gorgonopsians are not known to show consistent size variation within species.[2]

Classification

Although known from little material, what is preserved is enough to demonstrate that Phorcys was undoubtedly a gorgonopsian. Phorcys can be diagnosed and distinguished from all other gorgonopsians by the knob-like protuberances between the basal tubera and the occipital condyle on the underside of the skull. It is also distinguished from the only other known Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone gorgonopsian Eriphostoma by its larger size, vertical occiput and proportionately deeper zygomatic arch.[2]

To determine its relationship to other gorgonopsians, Kammerer and Rubidge performed a phylogenetic analysis using a complete dataset of all currently valid gorgonopsian genera. Similar to previous analyses, they recovered Nochnitsa and Viatkogorgon as the earliest-diverging (basal) gorgonopsians, with the remaining genera split into two clades, one containing Russian gorgonopsians and the other African.[7] Phorcys was found in a polytomy at the base of the African clade with Eriphostoma, Gorgonops and the remaining African gorgonopsians. This basal position among African gorgonopsians is consistent with its age, however, at the same time it draws out the existing ghost lineages (inferred ancestral lineages with missing fossil records) of the earlier-diverging Laurasian gorgonopsians back to the Wordian of the middle Permian at minimum. However, Kammerer and Rubidge considered this result preliminary due to the fragmentary nature of the known material, and noted that this position in the tree was weakly supported with only one coded characteristic (the straight orientation of the subtemporal zygoma) uniting it with other African gorgonopsians in this analysis (a trait that is itself variable in this clade). Nonetheless, an additional trait that wasn't coded for in their analysis may strengthen a relationship to the African gorgonopsians, the shape of the parabasisphenoid blade of the braincase. In Phorcys, this bone has only slight variation along its bottom margin, unlike the notable semi-circular blades of the Russian gorgonopsians but very comparable to those in the African clade.[2]

The cladogram below depicting the relationship of Phorcys in Gorgonopsia follows the results of Kammerer and Rubidge (2022):[2]

| Gorgonopsia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeoecology

In what would become the eastern Abrahamskraal Formation, Phorcys coexisted with an unusual assortment of therapsids and may have been part of a potentially distinct faunal assemblage from the rest of the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone. Two other therapsid genera are known only from these units, the predatory burnietamorph Pachydectes and the herbivorous early dicynodont Lanthanostegus, an unusual genus with markedly forward-facing eye sockets.[2][4] A scylacosaurid therocephalian is also known from the same horizon, estimated to have a skull roughly ~21 cm (8.3 in) long and comparable in size to, if not smaller than Phorcys. It is possible then that Phorcys was the top predator in this assemblage, in contrast to therapsid faunas in the upper Tapinocephalus AZ where therocephalians and the even larger anteosaurs dominated.[2]

Gorgonopsian ecological evolution

The presence of a relatively large-bodied early gorgonopsian like Phorcys so low in the Tapinocephalus AZ complicates previously proposed narratives for the ecological evolution of predatory therapsids. Prior to its discovery, gorgonopsians from older therapsid faunas were small—such as Viatkogorgon and Nochnitsa from Russia and the African Eriphostoma—and were in low abundance, while the largest and most diverse predators were either large therocephalians (namely scylacosaurids and lycosuchids) or giant anteosaurs. This lead palaeontologists Christian Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin to suggest in 2018 that gorgonopsians and therocephalians were niche partitioning by body size, with gorgonopsians occupying smaller predatory roles than larger therocephalians. Indeed, gorgonopsians only appeared to achieve larger sizes until after the extinction of the large therocephalians at the end-Guadalupian extinction event, which they suggested was an ecological release for gorgonopsians.[7]

Phorcys (as well as the similarly sized indeterminate gorgonopsian from the Eodicynodon AZ), however, demonstrate that early gorgonopsians did achieve large sizes comparable to later species and contemporary therocephalians, such as the scylacosaurid mentioned above. Indeed, while anteosaurs were the top predators in the upper Tapinocephalus AZ and were substantially larger than other predatory therapsids, the older Australosyodon from the underlying Eodicynodon AZ was relatively small and comparably sized to both Phorcys and scylacosaurids with a skull 26 cm (10 in) long. With Phorcys reaching comparable or potentially even greater sizes than either early anteosaurs and therocephalians, Kammerer and Rubidge contemplated the possibility that gorgonopsians like Phorcys may have been top predators in these early Middle Permian assemblages.[2]

It remains unclear why similarly large gorgonopsians appear to be absent from later Middle Permian faunas such as in the upper Tapinocephalus AZ. Gorgonopsian fossils are relatively under-sampled from these ages, so it is possible that they were rare parts of their ecosystems—although this would not explain why similar sized therocephalians were much more abundant. Alternatively, large therocephalians and gorgonopsians may have indeed been partitioned by size, but only following the extinction of large gorgonopsians like Phorcys in the Capitanian.[2]

References

- ↑ Rubidge, Bruce S., ed (1995). Biostratigraphy of the Beaufort Group (Karoo Supergroup). South African Committee for Stratigraphy. Biostratigraphic Series 1. Pretoria: Council for Geoscience. ISBN 978-1-87-506124-2. OCLC 35233710.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Kammerer, C. F.; Rubidge, B. S. (2022). "The earliest gorgonopsians from the Karoo Basin of South Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences 194: 104631. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2022.104631. Bibcode: 2022JAfES.19404631K.

- ↑ M.O. Day; B.S. Rubidge (2020). "Biostratigraphy of the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone (Beaufort Group, Karoo Supergroup), South Africa". South African Journal of Geology 123 (2): 149–164. doi:10.25131/sajg.123.0012. Bibcode: 2020SAJG..123..149D.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Rubidge, B. S.; Day, M. O.; Benoit, J. (2021). "New Specimen of the Enigmatic Dicynodont Lanthanostegus mohoii (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the Southwestern Karoo Basin of South Africa, and its Implications for Middle Permian Biostratigraphy". Frontiers in Earth Science 9: Article 668143. doi:10.3389/feart.2021.668143. Bibcode: 2021FrEaS...9..414R.

- ↑ Kammerer, Christian F. (2016). "Systematics of the Rubidgeinae (Therapsida: Gorgonopsia)" (in en). PeerJ 4: e1608. doi:10.7717/peerj.1608. ISSN 2167-8359. PMID 26823998.

- ↑ Kammerer, Christian F. (2014). "A Redescription of Eriphostoma microdon Broom, 1911 (Therapsida, Gorgonopsia) from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone of South Africa and a Review of Middle Permian Gorgonopsians". Early Evolutionary History of the Synapsida. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer. pp. 171–184. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6841-3_11. ISBN 978-94-007-6840-6.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kammerer, C. F.; Masyutin, V. (2018). "A new therocephalian (Gorynychus masyutinae gen. et sp. nov.) from the Permian Kotelnich locality, Kirov Region, Russia". PeerJ 6: e4933. doi:10.7717/peerj.4933. PMID 29900076.

Wikidata ☰ Q112885449 entry

|