Biology:Northern lion

| Northern lion | |

|---|---|

| |

| An Asiatic lion in Gir Forest National Park, India | |

| |

| Barbary lioness and cubs, New York Zoo, 1903 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. l. leo

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

formerly

| |

The Northern lion[2][3] (Panthera leo leo) is the nominate subspecies of the lion, which is present in the northern portion of Africa (particularly in West and Central Africa) and in India .[4][5] It is regionally extinct in southern Europe, West Asia and North Africa. In West and Central Africa, lions are restricted to fragmented and isolated populations, most of them declining. In India, there is a single surviving population in and around Gir Forest National Park.[6][7][8] The West African population is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List; this population is isolated and comprises fewer than 250 mature individuals.[9]

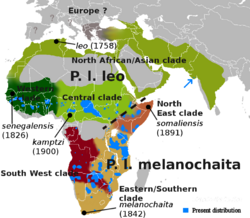

Results of a phylogeographic study indicate that lion populations in West and Central African range countries are genetically close to populations in India, forming a clade distinct from lion populations in Southern and East Africa.[10] In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group subsumed lion populations to two subspecies, namely P. l. leo and P. l. melanochaita. The Northern lion comprises four historically recognized subspecies, the Barbary lion, the Asiatic lion, the West African lion and the Central African lion.[4]

Taxonomic history

A lion from Constantine, Algeria was the type specimen for the specific name Felis leo used by Linnaeus in 1758.[11] Due to the location of Algeria in Africa, the term "Northern lion" was coined for lions living in the northern portion of the continent in 1865.[2][3] In the 19th and 20th centuries, several lion specimens from Africa and Asia were described and proposed as subspecies:

- In 1826, the Austrian zoologist Johann N. Meyer described a lion skin from Persia and named it Felis leo persicus. He also described a lion skin from Senegal under the name F. l. senegalensis.[12]

- In 1843, the French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville described a male lion from Nubia under the trinomen Felis leo nubicus that had been sent by Antoine Clot from Cairo to Paris and died in the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes in 1841.[13]

- In 1843, John Edward Gray described a specimen from Gambia in the British Museum of Natural History as Leo gambianus.[14]

- In 1900, Paul Matschie described a lion skull from northern Cameroon as Felis leo kamptzi.[15]

- In 1924, Joel Asaph Allen proposed the trinomen Leo leo azandicus for an individual that was killed in 1912 in northeastern Belgian Congo as part of a zoological collection comprising 588 carnivore specimens. Allen admitted a close relationship of this lion specimen to Leo leo massaicus from Kenya regarding cranial and dental characteristics, but argued that his type specimen differed in pelage coloration.[16]

In the following decades, there has been much debate among zoologists on the validity of proposed subspecies:

- In 1939, Glover Morrill Allen recognized Felis leo kamptzi and F. l. azandicus as valid taxa among ten lion subspecies.[17][18]

- The British taxonomist Reginald Innes Pocock subordinated lions to the genus Panthera in 1930 when he wrote about Asiatic lion specimens in the zoological collection of the British Museum of Natural History.[19]

- Three decades later, John Ellerman and Terence Morrison-Scott recognized only two lion subspecies in the Palearctic realm, namely the African (P. l. leo) and Asiatic lions (P. l. persica).[20]

- Some authors considered P. l. nubicus a valid subspecies and synonymous with P. l. massaica.[18][21][22]

- Some authors considered P. l. azandicus synonymous with P. l. massaicus and P. l. somaliensis, and P. l. kamptzi synonymous with P. l. senegalensis.[18][21]

- In 2005, Wallace Christopher Wozencraft recognized P. l. kamptzi, P. l. bleyenberghi and P. l. azandica as valid taxa.[1]

- In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors used P. l. leo for all African lion populations.[6]

- In 2017, lion populations in North, West and Central Africa and Asia were subsumed to P. l. leo by the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group, based on results of genetic research on lion samples.[4]

Genetic research

Since the beginning of the 21st century, several phylogenetic studies were conducted to aid clarifying the taxonomic status of lion samples kept in museums and collected in the wild. Scientists analysed between 32 and 197 lion samples from up to 22 countries. They all agree that the lion species comprises two evolutionary groups, one in the northern and eastern parts of its historical range, and the other in Southern and East Africa that diverged between 245,000 and 50,000 years ago. They assume that tropical rainforest and the East African Rift constituted major barriers between the two groups.[23][24][25][26][10] Based on this assessment, lion taxonomy has been revised as comprising two subspecies:[4]

- P. l. leo in the northern and eastern regions of its historical and contemporary distribution;

- P. l. melanochaita in the contemporary southern and East African range countries.

In a comprehensive study about the evolution of lions, 357 samples of 11 lion populations were examined, including some hybrid lions. The hybrids had descended from lions captured in Angola and Zimbabwe, and apparently West or Central Africa. Results indicated that four lions from Morocco did not exhibit any unique genetic characteristics and shared mitochondrial haplotypes H5 and H6 with lions from West Africa, and together with them were part of a major mtDNA grouping (lineage III) that also included Asiatic samples. This scenario was well in line with theories on lion evolution: lineage III developed in East Africa and traveled north and west in the first wave of lion expansions about 118,000 years ago. It apparently broke up into haplotypes H5 and H6 within Africa, and then into H7 and H8 in West Asia[24]

Results of genetic analyses indicate that lions in West Africa and northern parts of Central Africa form distinct lion clades, which are more closely related to North African and Asiatic lions than to lions in Southern Africa and southern parts of East Africa. Lions from North Africa and India however, do form one single clade.[26] Analysis of phylogenetic data of 194 lion samples from 22 different countries revealed that Central and West African lions form a phylogeographic group that probably diverged about 186,000–128,000 years ago from the melanochaita group in East and Southern Africa.[10]

Several lions kept in Ethiopia's Addis Ababa Zoo were found to be genetically similar to wild lions from Cameroon and Chad.[27]

Characteristics

The lion's fur varies in colour from light buff to dark brown. It has rounded ears and a black tail tuft. Average head-to-body length of male lions is 2.47–2.84 m (8.1–9.3 ft) with a weight of 148.2–190.9 kg (327–421 lb). Females are smaller and less heavy.[28]

A few lion specimens from West Africa obtained by museums have been described as having shorter manes than lions from other African regions.[18] In general, the West African lion is similar in general appearance and size as lions in other parts of Africa and Asia.[21]

Zoological specimens range in colour from light to dark tawny. Male skins have short manes, light manes, dark manes or long manes.[29] Taxonomists recognised that neither skin nor mane colour and length of lions can be adduced as distinct subspecific characteristics. Then they turned to measuring and comparing lion skulls and found that skull length of Barbary and Indian lion samples does not differ significantly, ranging from 280–311.7 mm (11.02–12.27 in) in females and 338–362 mm (13.3–14.3 in) in males.[29][18]

Distribution and habitat

Historically, the northern subspecies' range encompassed North Africa, southeastern Europe, the Arabian Peninsula and Middle East in Western Asia.[4] In these regions, lions occurred in:

- the Sahel, mountain ranges of the Sahara, Barbary Coast and Maghreb,[7][18][30]

- the eastern Mediterranean Basin and the Black Sea region,[28][31][32]

- reed swamps of Mesopotamia, wooded steppe vegetation and pistachio-almond woodlands in Iran,[33][34][35]

- the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent up to Rajastan and Bengal in North India.[36]

Today, the subspecies occurs in West and Central Africa and India.[4] It is regionally extinct in Gambia, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, the Western Sahara, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Palestine-Israel, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan . Its range has declined to the:[6]

- West African population surviving in a few protected areas of Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger, Benin and Nigeria.[9]

- Central African population surviving in protected areas of Cameroon, Central African Republic, northern parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern parts of Chad and South Sudan and in Ethiopia.[8][37][38][39]

- Asiatic population surviving only in Gir National Park and surrounding areas in India's state of Gujarat.[40]

Asiatic population

The Asiatic lion is the last wild lion population in Asia and restricted to Gir Forest National Park and surrounding areas in Gujarat, India . It is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List because of its small size and area of occupancy.[42] This population inhabits remnant forest habitats in the two hill systems of Gir and Girnar that comprise Gujarat's largest tracts of dry deciduous forest, thorny forest and savanna.[40]

Western and Central clades

The West African population is distributed south of the Sahara from Senegal in the west to Nigeria in the east. This population has lost 99% of its former range.[43] It is regionally extinct in Mauritania, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, and Togo, and possibly extinct in Guinea.[9] The largest West African subpopulation of between 246 and 466 individuals survives in the WAP-Complex, a large system of protected areas formed mainly by W, Arli, and Pendjari National Parks in Burkina Faso, Benin, and Niger.[43][44]

The range of the Central African lion clade reaches from the lower Niger river in West Africa to Ethiopia, encompassing Cameroon, Central African Republic, northern parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern parts of Chad and Sudan, and South Sudan.[10] Some Central African populations permanently inhabit rainforests and clearings in rainforest mixed with savannah grassland.[7] In Cameroon, lions are present in Bénoué National Park, and smaller lion groups also in Waza National Park.[5] Habitat in Waza National Park comprises foremost dry woodland that is partly flooded during the rainy season from July to December. In this protected area, two radio-collared male lions used home ranges of between 428 and 1,054 km2 (165 and 407 sq mi), both inside and outside the park. Three radio-collared females had home ranges of between 352 and 724 km2 (136 and 280 sq mi) and stayed inside the park during most of the survey period.[45] In the Central African Republic, lions are present in Bamingui-Bangoran National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Manovo-Gounda St. Floris and Awakaba National Parks, Aouk Aoukale, Yata Ngaya, Nana Barya and Zemongo Faunal Reserves, and in several hunting reserves of the country.[39] Estimated lion numbers in the country are generally thought to be unreliable.[5][46] Lions in Virunga National Park form a contiguous population with lions in the East African country of Uganda.[5][46] In Chad, lions inhabit Siniaka-Minia Faunal Reserve and Zakouma and Aouk National Parks, but have been extirpated in Manda National Park. Lions may still be present in pastoral rangelands and mountain ranges outside protected areas.[7] In 2004, the lion population in the country was estimated at maximum 225 individuals.[5] The following table shows estimates of lion population sizes between 2002 and 2012:

| Range countries | Area used in km2 | Estimated no. of individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Bénoué National Park complex, Cameroon | 14,682 | 200[37] |

| Waza National Park in Cameroon | 1,452 | 17[38] |

| Central African Republic | 339,418 | about 1,297[39] |

| Garamba National Park and Domaine Chasse Bili Uere, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 115,671 | 175−320[46][7] |

| Southeastern Chad | 133,408 | 400[46] |

| Southwestern Sudan | 331,834 | 375[46] |

| Boma and Gambela National Parks, South Sudan and Ethiopia | 106,941 | 500[46] |

| Omo National Park, Sudan and Ethiopia | 22,483 | 200[46] |

| other protected and non-protected areas, Ethiopia | 70,759 | 96[46] |

| Total | 1,136,648 | 3,260−3,305 |

The range of the Central African lion clade reaches from the lower Niger river in West Africa to Ethiopia, encompassing Cameroon, Central African Republic, northern parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern parts of Chad and Sudan, and South Sudan.[10] Some Central African populations permanently inhabit rainforests and clearings in rainforest mixed with savannah grassland.[7]

Contemporary lion distribution and habitat quality in savannahs of West and Central Africa was assessed in 2005, and Lion Conservation Units (LCU) mapped.[47] Educated guesses for size of populations in these LCUs ranged from 3,274 to 3,909 individuals between 2002 and 2012.[7][8]

| Range countries | Lion Conservation Units | Area in km2 |

|---|---|---|

| Senegal, Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea | Niokolo-Koba National Park | 90,384[8] |

| Guinea | National Park of Upper Niger | 613[8] |

| Benin, Burkina Faso, Niger | W-Arly-Pendjari Complex | 29,403[8] |

| Benin | three unprotected areas | 6,833[8] |

| Nigeria | Yankari National Park and Kainji National Park | 6,551[8] |

| Cameroon | Waza and Bénoué National Parks | 16,134[38] |

| Central African Republic | eastern part of the country; Bozoum and Nana Barya Faunal Reserves | 339,481[39] |

| Chad | southeastern part | 133,408[8] |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Garamba-Bili Uere | 115,671[47] |

| South Sudan, Sudan | 331,834[47] | |

| South Sudan, Ethiopia | Boma-Gambella | 106,941 |

| Ethiopia | South Omo, Nechisar, Bale, Welmel-Genale, Awash National Parks, Ogaden | 93,274[8] |

Former range

Lion populations in southern Europe and Transcaucasia were eradicated between the first and 10th centuries.[48][49][31]

Populations of the Asiatic lion became fragmented during the 19th century and regionally extinct in Turkey and the Middle East between the early and mid-20th century.[50][51][52]

North African populations also declined since the mid-19th century and were eradicated by the early 1960s.[53][30]

Behaviour and ecology

In Benin's Pendjari National Park, groups of lions range from 1–8 individuals. Outside the national park, groups are smaller and more single male lions occur.[54]

In general, lions prefer large prey species within a weight range of 190 to 550 kg (420 to 1,210 lb). They hunt large ungulates in the range of 40.0 to 270.0 kg (88.2 to 595.2 pounds) including zebra, warthog, blue wildebeest, impala, gemsbok, Thomson's gazelle, kob, giraffe and Cape Buffalo.[55] In India's Gir Forest National Park, lions predominantly kill chital, sambar, nilgai, cattle, buffalo and less frequently also wild boar. Outside the protected area where wild prey species do not occur, lions prey on buffalo and cattle, rarely also on camel. They kill most prey less than 100 m (330 ft) away from water bodies, charge prey from close range and drag carcasses into dense cover.[56]

The African lion and spotted hyena occupy a similar ecological niche, and where they coexist, they compete for prey and carrion; a review of data across several studies indicates a dietary overlap of 58.6%. Lions typically ignore spotted hyenas unless the lions are on a kill or are being harassed by the hyenas, while the latter tend to visibly react to the presence of lions, with or without the presence of food.[57]

Threats

In Africa, lions are killed pre-emptively or in retaliation for preying on livestock. Populations are also threatened by depletion of prey base, loss and conversion of habitat. Since 1996, African lion populations have been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.[6]

The West African lion is fragmented and isolated, comprising fewer than 250 mature individuals.[9] It is threatened by poaching and illegal trade of body parts. Lion body parts from Benin are smuggled to Niger, Nigeria, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Senegal and Guinea, and from Burkina Faso to Benin, Ivory Coast, Senegal and Guinea.[58] The Central African lion is threatened by loss of habitat and prey base and trophy hunting.[7][38][37]

Conservation

In India, the lion is protected, and included in CITES Appendix I.[59] African lions are included in CITES Appendix II.[6] In 2004, it was proposed in 2004 to list all lion populations in CITES Appendix I to reduce exports of lion trophies and implement a stricter permission process, due to the negative impact of trophy hunting.[60]

In 2006, a Lion Conservation Strategy for West and Central Africa was developed in cooperation between IUCN regional offices and several wildlife conservation organisations. The strategy envisages to maintain sufficient habitat, ensure a sufficient wild prey base, make lion-human coexistence sustainable and reduce factors that lead to further fragmentation of populations.[47]

In captivity

In 2006, 1258 captive lions were registered in the International Species Information System, including 13 individuals originating from Senegal to Cameroon, 115 from India and 970 with uncertain origin.[23]

Cultural significance

The title "Lion of Mali" was given to Marijata of the Mali Empire.[61][62]

The Cameroon national football team is nicknamed "The Indomitable Lions."[63]

Gallery

Jackie the MGM lion was said to be from Nubia

See also

- Wild cats in Africa: African leopard · African golden cat · Caracal · Serval · African wildcat · Sand cat · Cheetah

- Wild cats in West Asia and the Middle East: Arabian leopard · Anatolian leopard · Persian leopard · Iranian cheetah · Jungle cat · Asiatic wildcat · Pallas's cat

- Cape lion

- American lion

- History of lions in Europe

- Maneless lion

- Panthera leo fossilis

- Panthera spelaea

- Wildlife of Chad

- Wildlife of Gabon

- Wildlife of the Central African Republic

- Wildlife of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Physical comparison of tigers and lions

- Tiger versus lion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Panthera leo". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14000228.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wood, John George (1865). "Felidæ; or the Cat Tribe". The illustrated natural history. Boradway, Ludgate Hill, New York City: Routledge. p. 147. https://books.google.com/books?redir_esc=y&id=v1DPAAAAMAAJ&q=Northern+lion+Southern#v=snippet&q=Northern%20lion%20Southern&f=false.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wood, John George (1865). "Felidæ; or the Cat Tribe". Animal Kingdom. Boston: H. A. Brown. p. 147. https://books.google.com/books?id=BckGAAAAYAAJ&q=northern+lion+southern#v=snippet&q=northern%20lion%20southern&f=false.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V. et al. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group". Cat News (Special Issue 11). ISSN 1027-2992. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Bauer, H.; Van Der Merwe, S. (2004). "Inventory of free-ranging lions Panthera leo in Africa". Oryx 38 (1): 26–31.. doi:10.1017/S0030605304000055.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Template:IUCN

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Chardonnet, P. (2002). "Chapter II: Population Survey". Conservation of the African Lion : Contribution to a Status Survey. Paris: International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife, France & Conservation Force, USA. pp. 21–101.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.; Dollar, L.; Bauer, H.; Becker, M.; Dickman, A.; Funston, P.; Groom, R. et al. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion's (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity Conservation 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4. https://rd.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4/fulltext.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Template:IUCN

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag, K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P. et al. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports 6: 30807. doi:10.1038/srep30807. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep30807?WT.feed_name=subjects_evolution.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis Leo" (in Latin). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 41. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/726936. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ↑ Meyer, J. N. (1826). Dissertatio inauguralis anatomico-medica de genere felium. Doctoral thesis, University of Vienna.

- ↑ Blainville, H. M. D. de (1843). "F. leo nubicus". Ostéographie ou description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossils pour servir de base à la zoologie et la géologie. Vol 2. Paris: J. B. Baillière et Fils. p. 186.

- ↑ Gray, J. E. (1843). List of the specimens of Mammalia in the collection of the British Museum. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- ↑ Matschie, P. (1900). "Einige Säugethiere aus dem Hinterlande von Kamerun". Sitzungs-Berichte der Gesellschaft der Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 3: 87–100.

- ↑ Allen, J. A. (1924). "Carnivora Collected By The American Museum Congo Expedition". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 47: 73–281. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinamerican47ameruoft#page/223/mode/2up.

- ↑ Allen, G. M. (1939). "A Checklist of African Mammals". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College 83: 1–763. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinofmuseum83harv#page/242/mode/2up.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung 17: 167–280. https://archive.org/stream/verfentlichungen171974zool#page/178/mode/2up.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The lions of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural Historical Society 34: 638–665.

- ↑ Ellerman, J. R.; Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 (Second ed.). London: British Museum of Natural History. pp. 312–313. https://archive.org/stream/checklistofindia00elle#page/312/mode/2up.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo". Mammalian Species 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL2.0.CO;2]. http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/762_Panthera_leo.pdf.

- ↑ West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2013). "Panthera leo Lion". Mammals of Africa. Volume V. A & C Black. p. 149−159. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=B_07noCPc4kC&lpg=PP1&pg=RA4-PA149#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273 (1598): 2119–2125. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3555. PMID 16901830. PMC 1635511. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070808182526/http://www.adelaide.edu.au/acad/publications/papers/Barnett%20PRS%20lions.pdf.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H.; Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo Revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMID 18989457.

- ↑ Mazák, J. H. (2010). "Geographical variation and phylogenetics of modern lions based on craniometric data". Journal of Zoology 281 (3): 194−209.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J. et al. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa". Journal of Biogeography 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. http://dspace.learningnetworks.org/bitstream/1820/4311/1/2011_Bertola,Hooft,Vrieling,Weerd,York,Bauer,Prins,Haes,Iongh_GeneticDiversityEvolutionaryHistoryAndImplicationsForConservationOfTheLionInWestAndCentralAfrica.pdf.

- ↑ Bruche, S.; Gusset, M.; Lippold, S.; Barnett, R.; Eulenberger, K.; Junhold, J.; Driscoll, C. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2012). "A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia". European Journal of Wildlife Research 59 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Lion Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 138–179. ISBN 0-8008-8324-1.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Mazák, V. (1970). "The Barbary lion, Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758); some systematic notes, and an interim list of the specimens preserved in European museums". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 35: 34−45.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Black, S. A.; Fellous, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Roberts, D. L. (2013). "Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation". PLOS One 8 (4): e60174. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174. PMID 23573239.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992). "Lion". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4. https://archive.org/stream/mammalsofsov221992gept#page/82/mode/2up.

- ↑ Frazer, J. G., ed (1898). Pausanias's Description of Greece. London: Macmillan and Co.. https://archive.org/stream/pausaniassdescri01pausuoft/pausaniassdescri01pausuoft#page/n5/mode/2up.

- ↑ Blanford, W. T. (1876). "Felis leo L.". Zoology and Geology, Volume II. Eastern Persia: An Account of the Journeys of the Persian Boundary Commission, 1870-71-72. London: Macmillan and Co.. pp. 29–34.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera leo". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis Ltd.. pp. 212–222. https://archive.org/stream/PocockMammalia1/pocock1#page/n261/mode/2up.

- ↑ Khosravifard, S. and Niamir, A. (2016). "The lair of the lion in Iran". Cat News Special Issue 10: 14–17. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309410288.

- ↑ Kinnear, N. B. (1920). "The past and present distribution of the lion in south eastern Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 27: 34–39. https://archive.org/stream/journalofbombayn27192022bomb#page/32/mode/2up.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Croes, B. M.; Funston, P. J.; Rasmussen, G.; Buij, R.; Saleh, A.; Tumenta, P. N.; De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "The impact of trophy hunting on lions (Panthera leo) and other large carnivores in the Bénoué Complex, northern Cameroon". Biological Conservation 144 (12): 3064−3072.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Tumenta, P. N.; Kok, J. S.; Van Rijssel, J. C.; Buij, R.; Croes, B. M.; Funston, P. J.; De Iongh, H. H.; Udo de Haes, H. A. (2010). "Threat of rapid extermination of the lion (Panthera leo leo) in Waza National Park, Northern Cameroon". African Journal of Ecology 48 (4): 888−894.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Mésochina, P.; Mamang-Kanga, J. B.; Chardonnet, P.; Mandjo, Y.; Yaguémé, M. (2010), "Statut de conservation du lion (Panthera leo Linnaeus, 1758) en République Centrafricaine", Fondation IGF (Bangui)

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Singh, H. S.; Gibson, L. (2011). "A conservation success story in the otherwise dire megafauna extinction crisis: The Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) of Gir forest". Biological Conservation 144 (5): 1753–1757. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.02.009. http://www.dbs.nus.edu.sg/lab/cons-lab/documents/Singh_Gibson_Biol_Cons_2011.pdf.

- ↑ Humphreys, P.; Kahrom, E. (1999). "Lion". Lion and Gazelle: The Mammals and Birds of Iran. Avon: Images Publishing. pp. 77−80. ISBN 978-0951397763. https://books.google.com/books?id=esV0hccod0kC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Template:IUCN

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Henschel, P.; Coad, L.; Burton, C.; Chataigner, B.; Dunn, A.; MacDonald, D.; Saidu, Y.; Hunter, L. T. B. (2014). Hayward, M.. ed. "The Lion in West Africa is Critically Endangered". PLoS ONE 9 (1): e83500. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083500. PMID 24421889.

- ↑ Henschel, P.; Azani, D.; Burton, C.; Malanda, G.; Saidu, Y.; Sam, M.; Hunter, L. (2010). "Lion status updates from five range countries in West and Central Africa". Cat News 52: 34–39. http://www.panthera.org/sites/default/files/Henscheletal_2010_LionstatusupdatesfromfiverangecountriesinWestandCentralAfrica_CatNews.pdf.

- ↑ Bauer, H.; De Iongh, H.H. (2005). "Lion (Panthera leo) home ranges and livestock conflicts in Waza National Park, Cameroon". African Journal of Ecology 43 (3): 208−214.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 46.6 46.7 Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.; Dollar, L.; Bauer, H.; Becker, M.; Dickman, A.; Funston, P.; Groom, R. et al. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion's (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity Conservation 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4. https://rd.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4/fulltext.html.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 "Conservation Strategy for the Lion West and Central Africa", Cat Specialist Group / IUCN (Yaounde, Cameroon), 2006

- ↑ Alden, M. (2005). "Lions in paradise: Lion Similes in the Iliad and the Lion Cubs of IL. 18.318-22". The Classical Quarterly (55): 335–342.

- ↑ Bartosiewicz, L. (2008). "A Lion's Share of Attention: Archaeozoology and the historical record". Acta Archaeologica (2008): 759–773.

- ↑ Üstay, A. H. (1990). Hunting in Turkey. Istanbul: BBA.

- ↑ Hatt, R. T. (1959). The mammals of Iraq. Ann Arbor: Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Firouz, E. (2005). "Lion". The complete fauna of Iran. London, New York: I. B. Tauris. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-85043-946-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=t2EZCScFXloC&lpg=PA66&pg=PA65#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Pease, A. E. (1913). The Book of the Lion. London: John Murray. https://archive.org/stream/bookoflion1913alfr#page/112/mode/2up.

- ↑ Sogbohossou, E. A.; Bauer, H.; Loveridge, A.; Funston, P. J.; De Snoo, G. R.; Sinsin, B.; De Iongh, H. H. (2014). "Social structure of lions (Panthera leo) is affected by management in Pendjari Biosphere Reserve, Benin". PLOS One 9 (1): e84674.

- ↑ Hayward, M. W. and Kerley, G. I. (2005). "Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology 267 (3): 309–322.

- ↑ Chellam, R. and A. J. T. Johnsingh (1993). "Management of Asiatic lions in the Gir Forest, India". in Dunstone, N.; Gorman, M. L.. Mammals as predators: the proceedings of a symposium held by the Zoological Society of London and the Mammal Society, London. Volume 65 of Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. London: Zoological Society of London. pp. 409–423.

- ↑ Hayward, M. W. (2006). "Prey preferences of the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) and degree of dietary overlap with the lion (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology 270: 606–614. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00183.x. http://www.zbs.bialowieza.pl/g2/pdf/1598.pdf.

- ↑ Williams, V. L.; Loveridge, A. J.; Newton, D. J.; Macdonald, D. W. (2017). "Questionnaire survey of the pan-African trade in lion body parts". PLOS One 12 (10): e0187060. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187060. PMID 29073202. PMC 5658145. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0187060.

- ↑ Template:IUCN

- ↑ Nowell, K. (2004). "The Cat Specialist Group at CITES 2004". Cat News 41: 29.

- ↑ Lynch, P. A. (2004). African Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 0-8160-4892-4.

- ↑ Hogarth, C.; Butler, N. (2004). "Animal Symbolism (Africa)". in Walter, M. N.. Shamanism: An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culture, Volume 1. pp. 3–6. ISBN 1-57607-645-8.

- ↑ "Cameroon wins Africa Cup of Nations" (in en-UK). Daily Nation. http://www.nation.co.ke/sports/football/Africa-Cup-of-Nations/1102-3801304-allgt3/.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera leo. |

- Photos of West African lions at Pendjari National Park at flickr

- Wildlife extra: Lions from west and central Africa have more in common with Asiatic lion

- ROCAL West and Central African lion conservation network

- BBC News: Lions 'facing extinction in West Africa'

- Is this one of Central Africa's last lions? (2015)

- Take two: Gabon's lone lion makes another on-camera appearance (2016)

- The Rare Central African Lion - أسود حديقة الدندر فيديو فبراير 2017 (in Dinder National Park, YouTube)

- Draw between a lion and gorilla in a Central African primeval forest, late 19th century

- The Telegraph, August 2018: Pride of India

Wikidata ☰ Q221094 entry