Biology:Melon-headed whale

| Melon-headed whale | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

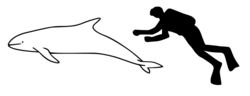

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Peponocephala Nishiwaki & Norris, 1966 |

| Species: | P. electra

|

| Binomial name | |

| Peponocephala electra (Gray, 1846)

| |

| |

| Range of the melon-headed whale | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Peponocephalus electrus | |

The melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra), also known less commonly as the electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish, is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae). The common name is derived from the head shape. Melon-headed whales are widely distributed throughout deep tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, but they are rarely encountered at sea. They are found near shore mostly around oceanic islands, such as Hawaii, French Polynesia, and the Philippines.

Taxonomy

The melon-headed whale is the only member of the genus Peponocephala. First recorded from a specimen collected in Hawaiʻi in 1841, the species was originally described as a member of the dolphin family and named Lagenorhynchus electra by John Edward Gray in 1846. The melon-headed whale was later determined to be sufficiently distinct from other Lagenorhynchus species to be accorded its own genus.[3] A member of the subfamily Globicephalinae, melon-headed whales are closely related to long-finned and short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas and G. macrorhynchus, respectively) and the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata).[4][5] Collectively, these species (including killer whales Orcinus orca, and false killer whales Pseudorca crassidens) are known by the common name ‘blackfish’. Melon-headed whales are one of the smallest species of cetacean (after pygmy killer whales) to have the word ‘whale’ in their common name.

Description

Melon-headed whales have a robust, dolphin-like body, a tapering, conical head (head shape triangular when viewed from above) with no discernible beak and a relatively tall, falcate (sickle-shaped) dorsal fin located near the middle of the back. Body coloration is charcoal-gray to dark-gray body. A dark face ‘mask’ extends from around the eye to the front of the melon and larger animals have whitish lips. Melon-headed whales have a dark colored dorsal cape that starts narrowly at the front of the head and dips down at a steep angle below the dorsal fin. The boundary between the darker cape and coloration on the flanks is often faint or diffuse. Both the mask and dorsal cape are often only visible in good lighting conditions. Compared to females, adult males have more rounded heads, longer flippers, taller dorsal fins, broader tail flukes and some have a pronounced ventral keel posterior to the anus.[6][7][8]

Melon-headed whales grow up to 2.75 m (9.0 ft) in length, and weigh up to 225 kg (496 lb), adult males being slightly larger than females.[7][9] Length at birth is approximately 1 m (3.3 ft).[10][11] Melon-headed whales are physically mature at 13–15 years and live up to 45 years.[7]

Similar species

At-sea, melon-headed whales can be confused with pygmy killer whales, which are very similar in appearance and share almost identical habitat and range.[12] The shape of the head, flippers and dorsal cape can be useful diagnostic features. Melon-headed whales have flippers with sharply pointed tips whereas pygmy killer whales have rounded flipper tips, and viewed from above, the head shape is more triangular than the rounded head of the pygmy killer whale.[8] The dorsal cape of melon-headed whales is rounded and dips much lower below the dorsal fin than that of pygmy killer whales, which dips at a relatively shallow angle and is more sharply demarcated in color between the dark cape and lighter flanks.[13] While both species have white around the mouth, in adult pygmy killer whales this can extend onto the face.[14]

Many of these traits are difficult to distinguish in challenging sea and/or lighting conditions, and behavior is often a useful aid to identification. Pygmy killer whales are slower moving (although melon-headed whales often log motionless at the surface), and are usually found in much smaller groups than melon-headed whales. Large groups (more than 100) are more likely to be melon-headed whales.[12][9] From a distance melon-headed whales could also be confused with false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens), but the much larger size–5–6 m (16–20 ft) adult length–long slender body shape and relatively smaller dorsal fin of false killer whales should distinguish them from melon-headed whales.

Stranded/post-mortem individuals can be easily identified by tooth number: melon-headed whales have 20 – 25 pairs of slender teeth (more similar to the teeth of smaller dolphins than other blackfish) in both the upper and lower jaws compared to 8–13 pairs of robust teeth in both the upper and lower jaws for pygmy killer whales.[13]

Geographic range and distribution

Melon-headed whales occur in deep tropical/subtropical oceanic waters, between 40°N and 35°S.[9] Although considered an offshore pelagic species, in some regions there are island-associated populations (e.g., Hawaiʻi) and they can be found close to shore associated with oceanic islands and archipelagoes, such as Palmyra and the Philippines .[15] Sightings or strandings at the extremes of their range are likely associated with extensions of warm currents.[9] Melon-headed whales are not known to be migratory.

Behavior

Foraging

Melon-headed whales feed primarily on pelagic and mesopelagic squid and small fish.[16][17] Crustaceans (shrimp) have also been reported from stomach contents.[8][16] Mesopelagic squid and fish species exhibit diel vertical migration behavior, inhabiting greater depths during the day and moving hundreds of meters to shallower depths after dusk to feed on plankton. Melon-headed whales feed at night, when their prey is within the upper 400 m (1,300 ft) of the water column.[16] In the Hawaiian Islands, individuals fitted with depth-transmitting satellite tags made night-time foraging dives that had an average range of 219.5–247.5 m (720–812 ft), with a maximum dive depth of 471.5 m (1,547 ft) recorded.[16]

Social

Melon-headed whales are a highly social species and usually travel in large groups of 100 – 500 individuals, with occasional sightings of herds as large as 1000–2000.[13] Large herds appear to consist of smaller subgroups that aggregate into larger groups.[18] Data from mass strandings in Japan suggest melon-headed whales may have a matrilineal social structure (i.e., related through female kin/groups organized around an older female and their relatives); the biased sex ratio (higher number of females) of the stranding groups suggesting mature males may move between groups.[11] While melon-headed whales associate in large groups (a common trait amongst the oceanic dolphins, in contrast to the smaller group sizes of other blackfish species) their social structure may be more stable and intermediate between the larger blackfish (pilot whales, killer whales and false killer whales) and smaller oceanic dolphins.[11] However, genetic studies of melon-headed whales across the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Ocean basins suggest that there is relatively high level of connectivity (inter-breeding) between populations.[19] This indicates that melon-headed whales may not show strong fidelity to their natal group (the group into which the individual was born) and that there are higher rates of movement of individuals between populations than in other blackfish species.[19] Larger group sizes may increase competition for prey resources, requiring large home ranges and broad-scale foraging movements.[19]

Observations of daily activity patterns of melon-headed whales near oceanic islands suggest they spend the mornings resting or logging in near-surface waters after foraging at night.[15] Surface activity (such as tail slapping and spyhopping) and vocalizations associated with socializing (communication whistles, rather than echolocation clicks used for foraging) increase during the afternoons.[15][20] The daily pattern of behavior observed in island-associated populations, combined with the larger group sizes of melon-headed whales (compared to that typically seen in other blackfish species) is more similar to the fission-fusion social structure of spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris).[15][19] These behavioral traits may relate to predation avoidance (bigger groups offer some protection from large oceanic sharks) and foraging habits (both species are nocturnal predators that prey on predictable, relatively abundant mesopelagic squid and fish that make diel vertical migrations from the deep-sea to the surface).

Melon-headed whales frequently associate with Fraser's dolphins (Lagenodelphis hosei), and are also sighted, although less commonly, in mixed herds with other dolphin species such as spinner dolphins, common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis), short-finned pilot whales and pantropical spotted dolphins (Stenella attenuata).[21][22]

A unique case of inter-species adoption between (presumably) an orphaned melon-headed whale calf and a common bottlenose dolphin mother was recorded in French Polynesia. The calf was first observed in 2014 at less than one month of age, swimming with the bottlenose dolphin female and her own biological offspring.[23] The melon-headed whale calf was observed suckling from the bottlenose dolphin female, and was repeatedly sighted with its adoptive/foster mother until 2018.[23]

In August 2017 off the island of Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi, a hybrid between a melon-headed whale and rough-toothed dolphin was observed travelling with a melon-headed whale amongst a group of rough-toothed dolphins.[24] The hybrid superficially resembled a melon-headed whale, but closer observation revealed it had features of both species and some features intermediate between the two species, particularly in head shape. Genetic testing of a skin biopsy sample confirmed that the individual was a hybrid between a female melon-headed whale and a rough-toothed dolphin male.[24]

Predators

Melon-headed whales may be predated upon by large sharks and killer whales.[25][26] Scars and wounds from non-lethal bites of cookie cutter sharks (Isitius brasiliensis) have been observed on free-ranging and stranded animals.[6][25]

Breeding

Little is known about the reproductive behavior of melon-headed whales. The most information comes from analyses of large stranding groups in Japanese waters, where sexual maturity for females is reached at 7 years of age.[6] Females give birth to a single calf every 3–4 years after a gestation of approximately 12 months.[10][11] Off Japan, the calving season appears to be long (from April to October) without an obvious peak.[11] In Hawaiian waters newborn melon-headed whales have been observed in all months except December, suggesting births occur year-round, but sightings of newborns peak between March and June.[25] Newborn melon-headed whales have been observed in April and June in the Philippines.[9] In the Southern Hemisphere calving also appears to occur over an extended period, from August to December.[10]

Strandings

Melon-headed whales are known to mass strand, often in groups numbering in the hundreds, indicative of the strong social bonds within herds of this species.[17] Mass strandings of melon-headed whales have been reported in Hawaiʻi, eastern Japan, the Philippines, northern Australia, Madagascar, Brazil and the Cape Verde Islands. Two of these mass stranding events have been linked to anthropogenic sonar, associated with naval activities in Hawaiʻi and high frequency multi-beam sonar used for oil and gas exploration in Madagascar.[27][28] The mass stranding at Hanalei Bay, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi is more precisely described as a ‘near’ mass stranding event, as the group of >150 melon-headed whales was prevented from stranding by human intervention.[27] The animals occupied the shallow waters of a confined bay for over 28 hours before being herded back into deeper waters by stranding response staff and volunteers, community members, state and federal authorities.[25][27] Only a single calf is known to have died on this occasion. The frequency of mass strandings of melon-headed whales appears to have increased over the past 30+ years.[29]

Movement

Melon-headed whales are fast swimmers; they travel in large, tightly packed groups and can create a lot of spray when surfacing, often porpoising (repeatedly leaping clear of the water surface at a shallow angle) when travelling at speed, and are known to spyhop and also may jump clear out of the water.[12] Melon-headed whales can be wary of boats, but in some regions will approach boats and bow-ride.[9][15]

Population status

The world population is unknown, but abundance estimates for large regions are approximately 45,000 in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean,[30] 2,235 in northern Gulf of Mexico [31] and in the Philippines 920 in the eastern Sulu Sea and 1,380 in Tañon Strait between Cebu and Negros Islands.[22] There are two known populations in Hawaiʻi: a population of approximately 450 individuals resident to shallower waters of the northwest side of Hawaiʻi Island (the ‘Kohola resident population’) and a much larger population of approximately 8,000 individuals that moves among the main Hawaiian Islands in deeper waters.[26]

Because the Hawaiʻi Island resident population has a restricted range (sightings have only been recorded off the northwest side of Hawaiʻi Island), and at times most of, or the entire resident population can be together in a single group, there is some concern that this population may be at risk from fisheries interactions, and exposure to anthropogenic noise,[21][25] particularly in light of U.S. Navy activities in the region, given the potential link between sonar and mass stranding events.[27]

Interactions with humans

Fisheries bycatch

Small cetaceans such as melon-headed whales are vulnerable to fisheries bycatch and may be injured or killed through interactions with fisheries or entanglement in lost or discarded netting. Small numbers of melon-headed whales have been caught incidentally in the longline fishery targeting tuna and swordfish off Mayotte,[32] and in driftnet fisheries in the Philippines,[33] Sri Lanka,[34] Ghana[35] and India.[36] In the eastern tropical Pacific purse-seine tuna fisheries, melon-headed whales have been rarely taken as bycatch.[8] and have not been recorded in the southwest Indian Ocean purse-seine fishery [32] Individual melon-headed whales exhibit injuries such as body scars and dorsal fin disfigurements likely due to interactions with fisheries in Hawaiʻi [26] and near Mayotte in the Mozambique Channel Islands.[37] The small numbers of injured individuals observed near Mayotte suggests that either interactions with the pelagic longline fishery in this region are rare for this species, or that individuals are more often killed rather than injured.[37] Mortalities are also likely in other countries where gill- or driftnet fisheries occur, however data on bycatch in many regions are sparse.[32] Animals caught as bycatch are sometimes used as bait in fisheries.[38]

Hunting

Individuals are taken for bait or human consumption in small cetacean subsistence and harpoon fisheries in several regions, including Sri Lanka,[34] the Caribbean,[39] the Philippines [40] and Indonesia.[41] At Dixcove port in Ghana, melon-headed whales are the third highest cetacean species caught for ‘marine bushmeat’ by artisanal fishermen, through both bycatch from drift gillnets and occasional directed catch.[35] The Japanese drive fishery has taken herds of melon-headed whales occasionally in the past.[7] In 2017/18 Japan increased the annual proposed catch quota to 704 individuals for the drive fishery at Taiji.[42]

Pollution

Environmental contaminants stemming from plastic debris, oil spills and dumping of industrial wastes at-sea, in addition to agricultural run-off from terrestrial sources, can lead to bioaccumulation in marine ecosystems and pose a threat to melon-headed whales (as with all marine mammals and long-lived, high trophic level consumers). Persistent organic pollutants (POPs)–include environmental contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), organochlorine pesticides e.g. dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethanes (DDTs) and hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCHs) and organobromine compounds such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)–are lipophilic (fat-soluble) and can accumulate in the blubber of marine mammals.[43] In high concentrations these pollutants can interfere with overall health, hormone levels and affect both the immune and reproductive systems.[43][44] Females with high contaminant levels can pass contaminant loads across the placenta or via lactation from mother to calf, leading to calf mortality.[45][46] Blubber samples from melon-headed whales stranded in Japan and Hawaiʻi were found to have PCB concentrations above thresholds considered toxic.[47][48] Off Japan the levels of PBDE and chlordane related compounds (CHL) in blubber increased during 1980–2000.[49]

Noise

Melon-headed whales may be vulnerable to impacts from anthropogenic (human generated) noise, such as those associated with military sonar activities, seismic surveys and high power multi-beam echosounder operations.[15][50] Based on previous stranding events linking mass strandings with sonar,[27][28] melon-headed whales appear to be one of the more sensitive species to mid-frequency active sonar (1 to 10 kHz) used in military operations and other types of sonar.[50] For island-associated populations, such as those in the Hawaiian archipelago,[21] Palmyra Atoll and the Marquesas Islands,[15] exposure to anthropogenic noise could result in displacement from important habitat.[50]

Whale watching

Regions in which melon-headed whales can be reliably sighted are few, however Hawai’i, the Maldives, the Philippines, and in the eastern Caribbean, especially around Dominica, are the best places to see them.[12] The International Whaling Commission (IWC) has guidelines for whale watching to ensure minimum disturbance to wildlife, but not every operator adheres to them.[51]

Conservation status

The melon-headed whale is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[1] There is little information available on current levels of bycatch and commercial hunting, therefore the potential effects on melon-headed whale populations are undetermined.[8] The current population trend is unknown.[1]

The species is listed on Appendix II [52] of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The melon-headed whale is included in the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU) and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU).[52] As with all other marine mammal species, the melon-headed whale is protected in United States waters under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).[53]

See also

- List of cetaceans

- Marine biology

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kiszka, J.; Brownell Jr.; R.L. (2019). "Peponocephala electra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T16564A50369125. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T16564A50369125.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/16564/50369125. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php.

- ↑ Nishiwaki, M. and K.S. Norris (1966). "A new genus, Peponocephala, for the odontocete cetacean species (Electra electra)". The Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 20: 95–100.

- ↑ Vilstrup, J. T. (2011). "Mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses of the Delphinidae with an emphasis on the Globicephalinae". BMC Evolutionary Biology 11 (1): 65. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-65. PMID 21392378.

- ↑ McGowen, M. R. (2019). "Phylogenomic Resolution of the Cetacean Tree of Life Using Target Sequence Capture". Systematic Biology 69 (3): 479–501. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz068. PMID 31633766.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Best, P.B. and P.D. Shaughnessy (1981). "First record of the melon-headed whale Peponocephala electra from South Africa". Ann. South Afr. Mus. 83: 33–47.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Miyazaki, N.; Y. Fujise; K. Iwata (1998). "Biological analysis of a mass stranding of melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) at Aoshima, Japan". Bulletin-National Science Museum Tokyo Series A 24: 31–60.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Perryman, W.L.; K. Danil (2018). "Melon-headed whale: Peponocephala electra". Encyclopedia of marine mammals (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Elsevier. pp. 593–595.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Perryman, W. L. (1994). S.H. Ridgway and R.J. Harrison. ed. Melon-headed whale Peponocephala electra Gray, 1846. London: Academic Press. pp. 363–386.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Bryden, M.; R. Harrison; R. Lear (1977). "Some aspects of the biology of Peponocephala electra (Cetacea: Delphinidae). I. General and reproductive biology". Marine and Freshwater Research 28 (6): 703–715. doi:10.1071/MF9770703.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Amano, M. (2014). "Life history and group composition of melon-headed whales based on mass strandings in Japan". Marine Mammal Science 30 (2): 480–493. doi:10.1111/mms.12050.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Carwardine, M. (2017). Mark Carwardine's Guide to Whale Watching in North America. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Jefferson, T.A.; M.A. Webber; R.L. Pitman (2015). Marine mammals of the world: a comprehensive guide to their identification (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 616.

- ↑ Baird, R.W. (2010). "Pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata) or false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens)? Identification of a group of small cetaceans seen off Ecuador in 2003". Aquatic Mammals 36 (3): 326. doi:10.1578/AM.36.3.2010.326.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2009). "Behavior of melon-headed whales, Peponocephala electra, near oceanic islands". Marine Mammal Science 25 (3): 639–658. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2009.00281.x. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=usdeptcommercepub.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 West, K. L. (2018). "Stomach contents and diel diving behavior of melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) in Hawaiian waters". Marine Mammal Science 34 (4): 1082–1096. doi:10.1111/mms.12507.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Jefferson, T.A.; N.B. Barros (1997). "Peponocephala electra". Mammalian Species (553): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3504200.

- ↑ Mullin, K. D. (1994). "First sightings of melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) in the Gulf of Mexico". Marine Mammal Science 10 (3): 342–348. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1994.tb00488.x.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Martien, K. K. (2017). "Unexpected patterns of global population structure in melon-headed whales Peponocephala electra". Marine Ecology Progress Series 577: 205–220. doi:10.3354/meps12203. Bibcode: 2017MEPS..577..205M.

- ↑ Baumann-Pickering, S. (2015). "Acoustic behavior of melon-headed whales varies on a diel cycle". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 69 (9): 1553–1563. doi:10.1007/s00265-015-1967-0. PMID 26300583.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Aschettino, J. M. (2012). "Population structure of melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) in the Hawaiian Archipelago: Evidence of multiple populations based on photo identification". Marine Mammal Science 28 (4): 666–689. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00517.x. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1220&context=usdeptcommercepub.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Dolar, M. L. L. (2023). "Abundance and distributional ecology of cetaceans in the central Philippines". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 8 (1): 93–111. doi:10.47536/jcrm.v8i1.706.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Carzon, P. (2019). "Cross-genus adoptions in delphinids: One example with taxonomic discussion". Ethology 125 (9): 669–676. doi:10.1111/eth.12916.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Baird, R. (2018). "Odontocete studies on the Pacific Missile Range Facility in August 2017: Satellite-tagging, photo-identification, and passive acoustic monitoring". Prepared for Commander, US Pacific Fleet, Pearl Harbor, HI.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Baird, R.W. (2016). The lives of Hawaii's dolphins and whales: Natural history and conservation. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Bradford, A. L. (2017). "Abundance estimates of cetaceans from a line-transect survey within the US Hawaiian Islands Exclusive Economic Zone". Fishery Bulletin 115 (2): 129–142. doi:10.7755/FB.115.2.1.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Southall, B. L. (2006). "Hawaiian melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra) mass stranding event of July 3-4, 2004". NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-31, Washington, DC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Southall, B. L. (2013). "Final report of the Independent Scientific Review Panel investigating potential contributing factors to a 2008 mass stranding of melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) in Antsohihy, Madagascar". Independent Scientific Review Panel.

- ↑ Brownell, Jr, R. (2006). "Mass strandings of melon-headed whales, Peponocephala electra: a worldwide review". International Whaling Commission Document SC/58/SM 8.

- ↑ Wade, P.R. and T. Gerrodette (1993). "Estimates of cetacean abundance and distribution in the eastern tropical Pacific". Report of the International Whaling Commission 43: 477–493.

- ↑ Waring, G. T. (2012). "US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments 2012". NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-2232013, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Fisheries Science Center Gloucester, MA: 419.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Kiszka, J. (2009). "Marine mammal bycatch in the southwest Indian Ocean: review and need for a comprehensive status assessment". Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science 7 (2): 119–136.

- ↑ Dolar, M. L. L. (1994). "Directed fisheries for cetaceans in the Philippines". Reports of the International Whaling Commission 44: 439–449.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Ilangakoon, A. (1997). "Species composition, seasonal variation, sex ratio and body length of small cetaceans caught off west, south-west and south coast of Sri Lanka". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 94: 298–306.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Van Waerebeek, K.; J.S. Debrah; P.K. Ofori-Danson (2014). "Cetacean landings at the fisheries port of Dixcove, Ghana in 2013-14: a preliminary appraisal". IWC Scientific Committee Document SC/65b/SM17, Bled, Slovenia: 12–24.

- ↑ Jeyabaskaran, R.; E. Vivekanandan (2013). "Marine mammals and fisheries interactions in Indian seas". Regional Symposium on Ecosystem Approaches to Marine Fisheries & Biodiversity: October 27–30, Kochi.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Kiszka, J.; D. Pelourdeau; V. Ridoux (2008). "Body scars and dorsal fin disfigurements as indicators interaction between small cetaceans and fisheries around the Mozambique Channel island of Mayotte". Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science 7 (2).

- ↑ Mintzer, V.J.; K. Diniz; T.K. Frazer (2018). "The use of aquatic mammals for bait in global fisheries". Frontiers in Marine Science 5: 191. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00191.

- ↑ Caldwell, D.K.; M.C. Caldwell; R.V. Walker (1976). "First records for Fraser's dolphin (Lagenodelphis hosei) in the Atlantic and the melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra) in the western Atlantic". Cetology 25: 1–4.

- ↑ Dolar, M. (1994). "Incidental takes of small cetaceans in fisheries in Palawan, central Visayas and northern Mindanao in the Philippines". Report of the International Whaling Commission 15: 355–363.

- ↑ Mustika, P.L.K. (2006). "Marine mammals in the Savu Sea (Indonesia): indigenous knowledge, threat analysis and management options". Masters Thesis. James Cook University, Townsville, QLD.

- ↑ International Whaling Commission (2018). "Report of the Scientific Committee". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 19 (Supplement): 1–114.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Bossart, G. (2011). "Marine mammals as sentinel species for oceans and human health". Veterinary Pathology 48 (3): 676–690. doi:10.1177/0300985810388525. PMID 21160025.

- ↑ Desforges, J.-P. W. (2016). "Immunotoxic effects of environmental pollutants in marine mammals". Environment International 86: 126–139. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.007. PMID 26590481.

- ↑ Schwacke, L. H. (2002). "Probabilistic risk assessment of reproductive effects of polychlorinated biphenyls on bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the southeast United States coast". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 21 (12): 2752–2764. doi:10.1002/etc.5620211232. PMID 12463575. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6709d6f34ccaef98ad8aa79c0052bea1f4b446ce.

- ↑ Borrell, A.; Bloch, D.; Desportes, G. (1995). "Age trends and reproductive transfer of organochlorine compounds in long-finned pilot whales from the Faroe Islands". Environmental Pollution 88 (3): 283–292. doi:10.1016/0269-7491(95)93441-2. PMID 15091540.

- ↑ Bachman, M. J. (2014). "Persistent organic pollutant concentrations in blubber of 16 species of cetaceans stranded in the Pacific Islands from 1997 through 2011". Science of the Total Environment 488: 115–123. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.073. PMID 24821437. Bibcode: 2014ScTEn.488..115B.

- ↑ Kajiwara, N. (2006). "Geographical distribution of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and organochlorines in small cetaceans from Asian waters". Chemosphere 64 (2): 287–295. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.013. PMID 16439003. Bibcode: 2006Chmsp..64..287K.

- ↑ Kajiwara, N. (2008). "Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and organochlorines in melon-headed whales, Peponocephala electra, mass stranded along the Japanese coasts: maternal transfer and temporal trend". Environmental Pollution 156 (1): 106–114. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2007.12.034. PMID 18272274.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Forney, K. A. (2017). "Nowhere to go: noise impact assessments for marine mammal populations with high site fidelity". Endangered Species Research 32: 391–413. doi:10.3354/esr00820.

- ↑ "IWC's General Principles for Whalewatching". International Whaling Commission. https://iwc.int/wwguidelines/.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 UNEP. "Species+". Compiled by UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. http://www.speciesplus.net.

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "Marine Mammal protection Act". International Affairs. https://www.fws.gov/international/laws-treaties-agreements/us-conservation-laws/marine-mammal-protection-act.html.

Further reading

- Carwardine, M., 2019. The Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Bloomsbury, London. 528pp.

- Jefferson, T.A., M.A. Webber, and R.L. Pitman, 2015. Marine mammals of the world: a comprehensive guide to their identification. 2nd ed, London: Academic Press. 616pp.

External links

- Dolphin mom adopts whale calf—a first

- Rare dolphin-whale hybrid spotted near Hawaii

- Melon-headed whale sounds

- Society for Marine Mammalogy

- Cascadia Research

- NOAA Fisheries

- IWC Responsible Whale Watching/handbook

- Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia.

- Official webpage of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region

Wikidata ☰ Q724349 entry

|