Medicine:Psychosocial distress

Psychosocial distress refers to the unpleasant emotions or psychological symptoms an individual has when they are overwhelmed, which negatively impacts their quality of life. Psychosocial distress is most commonly used in medical care to refer to the emotional distress experienced by populations of patients and caregivers of patients with complex chronic conditions such as cancer,[1] diabetes,[2] and cardiovascular conditions,[3] which confer heavy symptom burdens that are often overwhelming, due to the disease's association with death.[4] Due to the significant history of psychosocial distress in cancer treatment, and a lack of reliable secondary resources documenting distress in other contexts, psychosocial distress will be mainly discussed in the context of oncology.

Although the terms "Psychological" and "Psychosocial" are frequently used interchangeably, their definitions are dissimilar. While "Psychological" refers to an individual’s mental and emotional state, “Psychosocial” refers to how one's ideas, feelings, and behaviors influence and are influenced by social circumstances.[5] While psychological distress refers to the influence of internal processes on psychological wellbeing, psychosocial factors additionally include external, social, and interpersonal influences.[5]

Psychosocial distress is commonly caused by clinically related trauma, personal life changes, and extraneous stressors, which negatively influences the patient's mood, cognition, and interpersonal activity, eroding the patient's wellbeing and quality of life.[6] Symptoms manifest as psychological disorders, decreased ability to work and communicate, and a range of health issues related to stress and metabolism. Distress management aims to improve the disease symptoms and wellbeing of patients, it involves the screening and triage of patients to optimal treatments and careful outcome monitoring.

However, stigmatization of psychosocial distress is present in various sectors of society and cultures, causing many patients to avoid diagnosis and treatment, in which further action is required to ensure their safety. As an increasingly relevant field in medical care, further research is required for the development of better treatments for psychosocial distress, with relation to diverse demographics and advances in digital platforms.

Causes and Symptoms

Common causes of psychosocial distress include clinically related trauma, personal life changes, and extraneous stressors. The unsettling sensations experienced can cause individuals to respond to the stress in different ways, presenting psychological symptoms (e.g., excessive exhaustion, unhappiness, avoidance, dread and worry) that negative impacts an individual's well-being and quality of life.[6] When in psychosocial anguish, an individual may appear detached and avoid interpersonal communication. In addition, the ability to perform up to standard in the workplace can be impacted due to psychosocial discomfort. For example, the patient may find it difficult to stay focused or manage responsibilities sustainably.[6]

Clinical presentations of health issues may be observed, particularly for heart function. As a result of the body's increased release of stress hormones (e.g., cortisol) due to prolonged stress, blood pressure and heart rate will jump significantly.[7] Such histological responses are linked to an increase in:

- bodily inflammation

- risk of stroke

- cancer progression

- cardiovascular disease

- insomnia

- injury and suicidal tendencies

These clinical health issues often further exacerbate the original psychological symptoms. Furthermore, digestion, metabolism and other crucial bodily functions may be slowed down.[8][9]

Screening/Diagnosis

Prior to 2014, the implementation of evidence-based distress screening in the healthcare setting was scarce. In 2014, to increase objectivity in distress screening based on qualitative data, the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS) and Yale School of Nursing (YSN) collaborated to publish the Screening for Psychosocial Distress program, outlining the five steps- Screen, Evaluation, Referral, Follow-up and Documentation/Quality Improvement- to be carried out in psychosocial distress screening.[10]

1. Screening

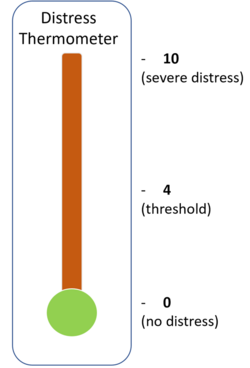

The Distress Thermometer (DT) is an established self-assessment tool that invites patients to score their perceived level of distress during the previous week on a scale from 0 (no distress) to 10 (severe, intolerable distress).[11] 39 different prompts classified as "Practical", "Family", "Emotional", "Spiritual", and "Physical" categories are utilized to evaluate the wellbeing of patients experiencing psychosocial distress. An average rating of >=4 points is regarded as significant, necessitating additional medical evaluation to determine the best course of medical care.

2. Evaluation

The recommended practice is to periodically assess ongoing and recovered cancer patients for anxiety and depressive symptoms during the course of their care, according to the Pan-Canadian Screening, Assessment and Care guideline that is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).[12][13] The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale can be used to evaluate symptoms of anxiety: a score of 0-4 implicates no symptoms, 5-9 implicates clement symptoms, 10-13 implicates moderate symptoms and 15-21 implicates severe symptoms.[14]

3. Referral

With reference to cancer patients in particular, in the event that typical management and treatment does not improve psychosocial distress outcomes, medical care professionals should provide patients with targeted referrals to mental health and social work institutions.[15]

4. Follow-up

Providing patients with follow up information, discussion and communication with their healthcare providers enables for further reevaluation upon the course of management or treatment that will be followed. Such communication also allows the provision of detailed patient-specific care.[16]

5. Documentation/Quality Improvement

All distress related patient information should be recorded in detail to reliably evaluate the course of the further action, according to the APOS Guidelines.[9]

Distress Management (DM)

Psychosocial Distress Management (DM) is mandatory in oncology care for every phase of disease treatment, and it involves screening, assessment, triage, intervention and outcome monitoring.[17][18] Each stage is personalized based on individual factors of age, race/ethnicity, sex, LGBTQ+, socio-economic status, physical/cognitive limitations, literacy, mental health/substance abuse history, as recommended by the APOS and Association of Oncology Social Work's (AOSW) 2021 consensus panel.[17]

Patients and their caregivers are proactively screened for distress at regular intervals and (optimally) every medical visit, as early detection is essential for avoidance of severe distress symptoms.[18] Frequency of screening increases with the stage of the disease, as the risk of distress increases with severity of disease symptoms.[17] Positively assessed patients are triaged to optimal interventions, while their clinical contacts and referrals are tracked by the health institution to ensure treatment is received.[19] These targeted referrals are made towards optimal evidence-based treatments based on the patient's specific psychosocial symptoms and individual factors, with adherence to the NCCN's 2020 guidelines.[20][18]

Treatment/ Intervention

The goal of DM is to relieve mental distress, raise the wellbeing of patients, and improve cancer treatment outcomes.[21] Evidence-based interventions are classified into 1st-line interventions and 2nd-line interventions, whose effectiveness vary depending on the patient's individual characteristics and symptoms.[17]

| Type of Intervention | Interventions/Treatments | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1st-line Interventions

(For moderate to severe distress) |

Psychosocial interventions (emotional/cognitive-based)[22][23] | Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) | ||

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) | ||

| Medication | Antidepressants, opioid analgesics | |

| NSAIDs | ||

| Psychoeducation[24] | Stress and self-management training | |

| Rehabilitation | Physical therapy | |

| Speech therapy | ||

| Occupational therapy | ||

| Exercise Interventions | Yoga | |

| Aerobic exercise | ||

| Tai Chi | ||

| 2nd-line Interventions

(For chronic distress in advanced disease) |

Group therapy | Meaning-centered group psychotherapy |

| Digital health interventions | eHealth self-management programs[25] | |

| Mobile applications | ||

| Return-to-work interventions | / | |

| Other interventions | Music intervention | |

| Systematic light therapy[26] | ||

| Massage therapy |

These interventions are often administered in combination, in which nonpharmacological psychosocial interventions are recommended over antidepressant medication due to its higher risk-benefit ratio.[27][17] Development for the use of digital platforms (such as mobile applications, internet-based, virtual reality) in DM is still in its early stages.[28][29][30] Outcome monitoring should be conducted to ensure treatment success.

Society & Culture

Stigma of Distress

File:Improving the Mental Health of Cancer Survivors- Stigma and Culturally Appropriate Conversations.webm Stigmatization of mental distress and illnesses is prevalent across many sectors of society.[31] This stigma is driven by presumptions that the patient suffering is to blame for their mental disorder, the socioeconomic disadvantages brought by mental illness (e.g., insurance, hiring discrimination[32]), and by health professionals reluctant to diagnose mental disorders due to such stigmatization, leading to a low level of development in psychiatric research and a low level of confidence in professional treatment effectiveness.[33]

Some cultures (e.g., rural) promote independence and self-affirmation that deter patients from reporting symptoms and receiving treatment.[34] Instead, alternatives such as religion and cognitive reframing (using prayers and narrative construction to encourage self-acceptance) are common coping mechanisms against distress.[32] Hence, in cases where patients decline psychosocial support, educational materials should be provided, accessibility improved via advertising, and comprehensive care integrated in the normal disease treatment.[17]

History of Psychosocial Distress in Oncology

In the 1990s, under recognition, medical coverage, and treatment of psychosocial symptoms stemmed from heavy stigmatization of the term “Psychological Distress”.[35] As a result, the term "Psychosocial Distress" was coined in 1999 by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), as a means to differentiate between the two and destigmatize such discussion between healthcare providers and patients.[36] At the same time, they released the first psychosocial distress guidelines, where early standards were set for distress management.[37] However, adherence to these guidelines was lacking until in 2015, "Psychosocial Support" was officialized as a criterion in Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation by the American College of Surgeons (ACS), which raised universal recognition of distress.[38]

Research directions

Research is needed for psychosocial care models, care disparities (for vulnerable populations), mental-emotional-relational health, population health (with demographic diversity) and digital health interventions, according to the APOS Roadmap.[39] In addition, there needs to be more research on how metastatic/advanced disease and demographic characteristics (e.g., gender influence[40]) can impact treatment effectiveness.[17] Following the COVID-19 epidemic (2019-2023), further development of psychosocial crisis prevention and intervention models in an epidemic scenario is essential.[41]

References

- ↑ Mehnert, Anja; Koch, Uwe; Schulz, Holger; Wegscheider, Karl; Weis, Joachim; Faller, Hermann; Keller, Monika; Brähler, Elmar et al. (December 2012). "Prevalence of mental disorders, psychosocial distress and need for psychosocial support in cancer patients – study protocol of an epidemiological multi-center study" (in en). BMC Psychiatry 12 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-70. ISSN 1471-244X. PMID 22747671.

- ↑ Shapiro, Michael S. (June 2022). "Special Psychosocial Issues in Diabetes Management: Diabetes Distress, Disordered Eating, and Depression" (in en). Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 49 (2): 363–374. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2021.11.007. PMID 35595489. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0095454321016377.

- ↑ Osborne, Michael T.; Shin, Lisa M.; Mehta, Nehal N.; Pitman, Roger K.; Fayad, Zahi A.; Tawakol, Ahmed (August 2020). "Disentangling the Links Between Psychosocial Stress and Cardiovascular Disease" (in en). Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 13 (8): e010931. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010931. ISSN 1941-9651. PMID 32791843.

- ↑ Nedjat-Haiem, Frances R.; Cadet, Tamara J.; Ferral, Alonzo J.; Ko, Eun Jeong; Thompson, Beti; Mishra, Shiraz I. (December 2020). "Moving closer to death: understanding psychosocial distress among older veterans with advanced cancers" (in en). Supportive Care in Cancer 28 (12): 5919–5931. doi:10.1007/s00520-020-05452-7. ISSN 0941-4355. PMID 32281033. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-020-05452-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hasa (2023-01-08). "What is the Difference Between Psychosocial and Psychological" (in en-US). https://pediaa.com/what-is-the-difference-between-psychosocial-and-psychological/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Strada, E. Alessandra (September 2019). "Psychosocial Issues and Bereavement". Primary Care 46 (3): 373–386. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2019.05.004. ISSN 1558-299X. PMID 31375187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31375187/.

- ↑ "Stress management Stress basics" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/basics/stress-basics/hlv-20049495.

- ↑ Serafini, Gianluca; Pompili, Maurizio; Innamorati, Marco; Iacorossi, Giulia; Cuomo, Ilaria; Della Vista, Mariarosaria; Lester, David; De Biase, Luciano et al. (2010-11-25). "The Impact of Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidality on Quality of Life and Functional Status of Patients With Congestive Heart Failure and Hypertension: An Observational Cross-Sectional Study". The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 12 (6). doi:10.4088/PCC.09m00916gry. ISSN 1555-211X. PMID 21494352. PMC 3067981. http://www.psychiatrist.com/pcc/article/pages/2010/v12n06/09m00916gry.aspx.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pirl, William F.; Fann, Jesse R.; Greer, Joseph A.; Braun, Ilana; Deshields, Teresa; Fulcher, Caryl; Harvey, Elizabeth; Holland, Jimmie et al. (2014-10-01). "Recommendations for the implementation of distress screening programs in cancer centers: Report from the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS), Association of Oncology Social Work (AOSW), and Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) joint task force: Distress Screening Recommendations" (in en). Cancer 120 (19): 2946–2954. doi:10.1002/cncr.28750. PMID 24798107. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.28750.

- ↑ Lazenby, Mark; Tan, Hui; Pasacreta, Nick; Ercolano, Elizabeth; McCorkle, Ruth (2015). "The five steps of comprehensive psychosocial distress screening". Current Oncology Reports 17 (5): 447. doi:10.1007/s11912-015-0447-z. ISSN 1534-6269. PMID 25824699.

- ↑ Holland, Jimmie C.; Gooen-Piels, Jane (2003). "Guidelines for Recognition of Psychosocial Distress" (in en). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th Edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK12457/.

- ↑ Howell, Doris; Oliver, Thomas K.; Keller-Olaman, Sue; Davidson, Judith; Garland, Sheila; Samuels, Charles; Savard, Josée; Harris, Cheryl et al. (2013-05-25). "A Pan-Canadian practice guideline: prevention, screening, assessment, and treatment of sleep disturbances in adults with cancer". Supportive Care in Cancer 21 (10): 2695–2706. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1823-6. ISSN 0941-4355. PMID 23708820. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1823-6.

- ↑ Andersen, Barbara L.; DeRubeis, Robert J.; Berman, Barry S.; Gruman, Jessie; Champion, Victoria L.; Massie, Mary Jane; Holland, Jimmie C.; Partridge, Ann H. et al. (2014-05-20). "Screening, Assessment, and Care of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Adults With Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline Adaptation" (in en). Journal of Clinical Oncology 32 (15): 1605–1619. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611. ISSN 0732-183X. PMID 24733793.

- ↑ Kroenke, Kurt; Spitzer, Robert L.; Williams, Janet B. W. (September 2001). "The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure" (in en). Journal of General Internal Medicine 16 (9): 606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. ISSN 0884-8734. PMID 11556941.

- ↑ Estes, Judith M.; Karten, Clare (2014-10-01). "Nursing Expertise and the Evaluation of Psychosocial Distress in Patients With Cancer and Survivors". Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 18 (5): 598–600. doi:10.1188/14.CJON.598-600. ISSN 1092-1095. PMID 25253116. http://cjon.ons.org/cjon/18/5/nursing-expertise-and-evaluation-psychosocial-distress-patients-cancer-and-survivors.

- ↑ Network, National Comprehensive Cancer (2008). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1572824500572420352. PDF

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 Deshields, Teresa L.; Wells‐Di Gregorio, Sharla; Flowers, Stacy R.; Irwin, Kelly E.; Nipp, Ryan; Padgett, Lynne; Zebrack, Brad (2021-09-07). "Addressing distress management challenges: Recommendations from the consensus panel of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society and the Association of Oncology Social Work" (in en). CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71 (5): 407–436. doi:10.3322/caac.21672. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 34028809. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21672.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Holland, Jimmie C.; Andersen, Barbara; Breitbart, William S.; Buchmann, Luke O.; Compas, Bruce; Deshields, Teresa L.; Dudley, Moreen M.; Fleishman, Stewart et al. (February 2013). "Distress Management" (in en). Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 11 (2): 190–209. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. ISSN 1540-1405. PMID 23411386.

- ↑ Donovan, Kristine A.; Deshields, Teresa L.; Corbett, Cheyenne; Riba, Michelle B. (2019-10-01). "Update on the Implementation of NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management by NCCN Member Institutions" (in en-US). Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 17 (10): 1251–1256. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2019.7358. ISSN 1540-1405. PMID 31590156. https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/17/10/article-p1251.xml.

- ↑ Levy, Michael H.; Back, Anthony; Benedetti, Costantino; Billings, J. Andrew; Block, Susan; Boston, Barry; Bruera, Eduardo; Dy, Sydney et al. (April 2009). "Palliative Care". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 7 (4): 436–473. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. ISSN 1540-1405. PMID 19406043. https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/7/4/article-p436.xml.

- ↑ Jacobsen, P. B.; Jim, H. S. (2008-03-19). "Psychosocial Interventions for Anxiety and Depression in Adult Cancer Patients: Achievements and Challenges" (in en). CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 58 (4): 214–230. doi:10.3322/CA.2008.0003. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 18558664. http://doi.wiley.com/10.3322/CA.2008.0003.

- ↑ Warth, Marco; Zöller, Joshua; Köhler, Friederike; Aguilar-Raab, Corina; Kessler, Jens; Ditzen, Beate (2020-01-21). "Psychosocial Interventions for Pain Management in Advanced Cancer Patients: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis" (in en). Current Oncology Reports 22 (1): 3. doi:10.1007/s11912-020-0870-7. ISSN 1534-6269. PMID 31965361. PMC 8035102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-020-0870-7.

- ↑ Sheinfeld Gorin, Sherri; Krebs, Paul; Badr, Hoda; Janke, Elizabeth Amy; Jim, Heather S. L.; Spring, Bonnie; Mohr, David C.; Berendsen, Mark A. et al. (2012-02-10). "Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology 30 (5): 539–547. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0437. ISSN 1527-7755. PMID 22253460.

- ↑ DEVINE, ELIZABETH C.; REIFSCHNEIDER, ELLEN (July 1995). "A Meta-Analysis of the Effects Of Psychoeducational Care in Adults with Hypertension". Nursing Research 44 (4): 237–245. doi:10.1097/00006199-199507000-00009. ISSN 0029-6562. PMID 7624235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199507000-00009.

- ↑ Xu, Anqi; Wang, Yinping; Wu, Xue (December 2019). "Effectiveness of e‐health based self‐management to improve cancer‐related fatigue, self‐efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients: Systematic review and meta‐analysis" (in en). Journal of Advanced Nursing 75 (12): 3434–3447. doi:10.1111/jan.14197. ISSN 0309-2402. PMID 31566769. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.14197.

- ↑ Wu, Lisa M.; Amidi, Ali; Valdimarsdottir, Heiddis; Ancoli-Israel, Sonia; Liu, Lianqi; Winkel, Gary; Byrne, Emily E.; Sefair, Ana Vallejo et al. (2018-01-15). "The Effect of Systematic Light Exposure on Sleep in a Mixed Group of Fatigued Cancer Survivors" (in en). Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 14 (1): 31–39. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6874. ISSN 1550-9389. PMID 29198295.

- ↑ DeRubeis, Robert J.; Hollon, Steven D.; Amsterdam, Jay D.; Shelton, Richard C.; Young, Paula R.; Salomon, Ronald M.; O’Reardon, John P.; Lovett, Margaret L. et al. (2005-04-01). "Cognitive Therapy vs Medications in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Depression" (in en). Archives of General Psychiatry 62 (4): 409–416. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 15809408. http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409.

- ↑ Breitbart, William, ed (February 2021) (in en). Psycho-Oncology (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780190097653.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-009765-3. https://academic.oup.com/book/33121.

- ↑ Beatty, Lisa; Dhillon, Haryana (February 2021), Breitbart, William S.; Butow, Phyllis N.; Jacobsen, Paul B. et al., eds., "Digital Health Interventions for Psychosocial Distress (Anxiety and Depression) in Cancer" (in en), Psycho-Oncology (Oxford University Press): pp. 543–549, doi:10.1093/med/9780190097653.003.0069, ISBN 978-0-19-009765-3, https://academic.oup.com/book/33121/chapter/284170002, retrieved 2023-03-12

- ↑ Yap, Jia Min; Tantono, Natalia; Wu, Vivien Xi; Klainin-Yobas, Piyanee (2021-11-26). "Effectiveness of technology-based psychosocial interventions on diabetes distress and health-relevant outcomes among type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (in en). Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare: 1357633X2110583. doi:10.1177/1357633X211058329. ISSN 1357-633X. PMID 34825839. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1357633X211058329.

- ↑ Zissi, Anastasia (2021). "Social stigma in mental illness: A review of concepts, methods and empirical evidence". Psychiatriki 33 (2): 149–156. doi:10.22365/jpsych.2021.039. PMID 34390566. https://www.psychiatriki-journal.gr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1705&lang=en.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Akin-Odanye, Elizabeth O.; Husman, Anisah J. (2021). "Impact of stigma and stigma-focused interventions on screening and treatment outcomes in cancer patients". ecancermedicalscience 15: 1308. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2021.1308. ISSN 1754-6605. PMID 34824631.

- ↑ Holland, Jimmie C.; Kelly, Brian J.; Weinberger, Mark I. (2010-04-01). "Why Psychosocial Care is Difficult to Integrate into Routine Cancer Care: Stigma is the Elephant in the Room" (in en-US). Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 8 (4): 362–366. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2010.0028. ISSN 1540-1405. PMID 20410331. https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/8/4/article-p362.xml.

- ↑ DeGuzman, Pamela Baker; Vogel, David L.; Bernacchi, Veronica; Scudder, Margaret A.; Jameson, Mark J. (2022-05-19). "Self-reliance, Social Norms, and Self-stigma as Barriers to Psychosocial Help-Seeking Among Rural Cancer Survivors With Cancer-Related Distress: Qualitative Interview Study". JMIR Formative Research 6 (5): e33262. doi:10.2196/33262. ISSN 2561-326X. PMID 35588367.

- ↑ Board, Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy; Hewitt, Maria; Herdman, Roger; Holland, Jimmie (2004) (in en). Barriers to Appropriate Use of Psychosocial Services. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215941/.

- ↑ "NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. National Comprehensive Cancer Network". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.) 13 (5A): 113–147. May 1999. ISSN 0890-9091. PMID 10370925. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10370925/.

- ↑ Lowery, Amy E.; Holland, Jimmie C. (November 2011). "Screening cancer patients for distress: guidelines for routine implementation". Community Oncology 8 (11): 502–505. doi:10.1016/s1548-5315(12)70100-6. ISSN 1548-5315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1548-5315(12)70100-6.

- ↑ Commission on Cancer. "Optimal Resources for Cancer Care.". Cancer Program Standards 2015: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care.. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/commission-on-cancer/standards-and-resources/.

- ↑ American Psychosocial Oncology Society (2021). "Research, Practice, and Policy Imperatives for Psychosocial Care: A Roadmap in a New Era of Value‐Based Cancer Care". American Psychosocial Oncology Society. https://apos-society.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/APOS-Roadmap_FINAL-Print-2.23.21.pdf.

- ↑ Linden, Wolfgang; Vodermaier, Andrea; MacKenzie, Regina; Greig, Duncan (December 2012). "Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age" (in en). Journal of Affective Disorders 141 (2–3): 343–351. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. PMID 22727334. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165032712002212.

- ↑ Dubey, Souvik; Biswas, Payel; Ghosh, Ritwik; Chatterjee, Subhankar; Dubey, Mahua Jana; Chatterjee, Subham; Lahiri, Durjoy; Lavie, Carl J. (September 2020). "Psychosocial impact of COVID-19" (in en). Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 14 (5): 779–788. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035. PMID 32526627.

|