Biography:Principalía

The Principalía or noble class[1](p331) was the ruling and usually educated upper class in the pueblos of the Spanish Philippines, comprising the gobernadorcillo (who had functions similar to a town mayor), and the cabezas de barangay (heads of the barangays) who governed the districts.[lower-alpha 1] The distinction or status of being part of the principalía was a hereditary right.[lower-alpha 2] However, it could also be acquired, as attested by the royal decree of 20 December 1863 (signed in the name of Queen Isabella II by the Minister of the Colonies, José de la Concha).[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5][4]:p1 cols 1–4

This distinguished upper class was exempted from tribute (tax) to the Spanish crown during the colonial period.[lower-alpha 6] Colonial documents would refer to them as "de privilegio y gratis", in contrast to those who pay tribute ("de pago").[6] It was the true aristocracy and the true nobility of colonial Philippines,[7](pp60–61)[lower-alpha 7][lower-alpha 8][9](p232–235) which could be roughly comparable to the patrician class of ancient Rome. The principales (members of the principalía) traced their origin from the pre‑colonial royal and noble class of Datu of the established kingdoms, rajahnates, confederacies, and principalities,[10](p19) as well as the lordships of the smaller ancient social units called barangays[11](p223)[lower-alpha 9] in Visayas, Luzon, and Mindanao.[lower-alpha 10] The members of this class enjoyed exclusive privileges: only the members of the principalía were allowed to vote, be elected to public office, and be addressed by the title: Don or Doña.[lower-alpha 11][2](p624)[13](p218) The use of the honorific addresses "Don" and "Doña" was strictly limited to what many documents during the colonial period[14] would refer to as "vecinas y vecinos distinguidos".[lower-alpha 12]

For the most part, the social privileges of the nobles were freely acknowledged as befitting their greater social responsibilities. The gobernadorcillo during that period received a nominal salary and was not provided government funds for public services. In fact more often the gobernadorcillo had to maintain government of his municipality by looking after the post office and the jailhouse, and by managing public infrastructure, using personal resources.[1](p326)[16](p294)

Principales also provided assistance to parishes by helping in the construction of church buildings, and in the pastoral and religious activities of the priests who, being usually among the few Spaniards in most colonial towns, had success in winning the goodwill of the natives. More often, the clergy were the sole representatives of Spain in many parts of the archipelago.[lower-alpha 13] Under the Patronato Real of the Spanish crown, these Spanish churchmen were also the king's effective ambassadors,[lower-alpha 14] and promoters[lower-alpha 15] of the realm.[18](p726-727;735)

With the end of Spanish sovereignty over the Philippines after the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the introduction of a democratic, republican system during the American Occupation, the Principalía and their descendants lost their legal authority and social privileges. Many were, however, able to integrate into the new socio-political structure, retaining some degree of influence and power.[lower-alpha 16]

Historical background

Pre-colonial principalities

From the beginning of the colonial period in the Philippine, the Spanish government built on the traditional pre‑conquest socio‑political organization of the barangay and co‑opted the traditional indigenous princes and their nobles, thereby ruling indirectly.[lower-alpha 17][lower-alpha 18] The barangays in some coastal places in Panay,[lower-alpha 19][21] Manila, Cebu, Jolo, and Butuan, with cosmopolitan cultures and trade relations with other countries in Asia, were already established principalities (Kinadatuan) before the coming of the Spaniards. In other regions, even though the majority of these barangays were not large settlements, yet they had organized societies dominated by the same type of recognized aristocracy and lordships (with birthright claim to allegiance from followers), as those found in more established, richer and more developed principalities.[lower-alpha 20] The aristocratic group in these pre‑colonial societies was called the datu class. Its members were presumably the descendants of the first settlers on the land or, in the case of later arrivals, of those who were datus at the time of migration or conquest.

The duty of the datus was to rule and govern their subjects and followers, and to assist them in their interests and necessities. What the chiefs received from their followers was: to be held by them in great veneration and respect; and they were served in their wars and voyages, and in their tilling, sowing, fishing, and the building of their houses. The natives attended to these duties very promptly, whenever summoned by their chief. They also paid their chief tribute (which they called buwis) in varying quantities, in the crops that they gathered.[12](Chapter VIII) The descendants of such chiefs, and their relatives, even though they did not inherit the Lordship, were held in the same respect and consideration, and were all regarded as nobles and as persons exempt from the services rendered by the others, or the plebeians (timawas).[12](Chapter VIII) The same right of nobility and chieftainship was preserved for the women, just as for the men.[12](Chapter VIII)

Some of these principalities and lordships have remained, even until the present, in unHispanicized [lower-alpha 21] and mostly Lumad and Muslim parts of the Philippines, in some regions of Mindanao.[22](pp127–147)

Pre-colonial principalities in the Visayas

In more developed barangays in Visayas, e.g., Panay, Bohol and Cebu (which were never conquered by Spain but were incorporated into the Spanish sphere of influence as vassals by means of pacts, peace treaties, and reciprocal alliances),[12](p33)[22](p4)[lower-alpha 22] the datu class was at the top of a divinely sanctioned and stable social order in a territorial jurisdiction called in the local languages as Sakop or Kinadatuan (Kadatuan in ancient Malay; Kedaton in Javanese; and Kedatuan in many parts of modern Southeast Asia), which is elsewhere commonly referred to also as barangay.[lower-alpha 23] This social order was divided into three classes. The Kadatuan, which is also called Tumao (members of the Visayan datu class), were compared by the Boxer Codex to the titled lords (Señores de titulo) in Spain. As Agalon or Amo (lords),[lower-alpha 24] the datus enjoyed an ascribed right to respect, obedience, and support from their oripun (commoner) or followers belonging to the third order. These datus had acquired rights to the same advantages from their legal "timawa" or vassals (second order), who bind themselves to the datu as his seafaring warriors. "Timawas" paid no tribute, and rendered no agricultural labor. They had a portion of the datu's blood in their veins. The Boxer Codex calls these "timawas" knights and hidalgos. The Spanish conquistador, Miguel de Loarca, described them as "free men, neither chiefs nor slaves". In the late 1600s, the Spanish Jesuit priest Fr. Francisco Ignatio Alcina, classified them as the third rank of nobility (nobleza).[22](pp102, 112–118)

To maintain purity of bloodline, datus marry only among their kind, often seeking high ranking brides in other barangays, abducting them, or contracting brideprices in gold, slaves and jewelry. Meanwhile, the datus kept their marriageable daughters secluded for protection and prestige.[23] These well‑guarded and protected highborn women were called "binokot",[24](pp290–291) the datus of pure descent (four generations) were called "potli nga datu" or "lubus nga datu",[22](p113) while a woman of noble lineage (especially the elderly) was addressed by the Visayans (of Panay) as "uray" (meaning: pure as gold), e.g., uray Hilway.[24](p292)

Pre-colonial principalities in the Tagalog region

The different type of culture prevalent in Luzon gave a less stable and more complex social structure to the pre‑colonial Tagalog barangays of Manila, Pampanga and Laguna. Enjoying a more extensive commence than those in Visayas, having the influence of Bornean political contacts, and engaging in farming wet rice for a living, the Tagalogs were described by the Spanish Augustinian Friar Martin de Rada as more traders than warriors.[22](pp124–125)

The more complex social structure of the Tagalogs was less stable during the arrival of the Spaniards because it was still in a process of differentiating. The Jesuit priest Francisco Colin made an attempt to give an approximate comparison of it with the Visayan social structure in the middle of the seventeenth century. The term datu or lakan, or apo refers to the chief, but the noble class to which the datu belonged or could come from was the maginoo class. One may be born a maginoo, but he could become a datu by personal achievement. In the Visayas, if the datu had the personality and economic means, he could retain and restrain competing peers, relatives, and offspring. The term timawa came into use in the social structure of the Tagalogs within just twenty years after the coming of the Spaniards. The term, however, was being applied to former alipin (third class) who have escaped bondage by payment, favor, or flight. The Tagalog timawas did not have the military prominence of the Visayan timawa. The warrior class in the Tagalog society was present only in Laguna, and they were called the maharlika class. At the early part of the Spanish regime, the number of their members who were coming to rent land from their datus was increasing.[22](pp124–125)

Unlike the Visayan datus, the lakans and apos of Luzon could call all non‑maginoo subjects to work in the datu's fields or do all sorts of other personal labor. In the Visayas, only the oripuns were obliged to do that, and to pay tribute besides. The Tagalog who works in the datu's field did not pay him tribute, and could transfer their allegiance to another datu. The Visayan timawa neither paid tribute nor performed agricultural labor. In a sense, they were truly aristocrats. The Tagalog maharlika did not only work in his datu’s field, but could also be required to pay his own rent. Thus, all non‑maginoo formed a common economic class in some sense, though this class had no designation.[22](pp124–125)

The civilization of the pre‑colonial societies in the Visayas, northern Mindanao, and Luzon were largely influenced by Hindu and Buddhist cultures. As such, the datus who ruled these principalities (such as Butuan, Cebu, Panay, Mindoro and Manila) also shared the many customs of royalties and nobles in southeast Asian territories (with Hindu and Buddhist cultures), especially in the way they used to dress and adorn themselves with gold and silk. The Boxer Codex bears testimony to this fact. The measure of the prince's possession of gold and slaves was proportionate to his greatness and nobility.[24](p281) The first westerners who came to the archipelago observed that there was hardly any "Indian" who did not possess chains and other articles of gold.[25](p201)

The Filipino Nobility during the Colonial Period

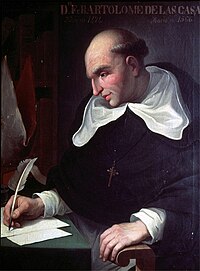

When the Spaniards expanded their dominion to the Americas and, later on, to the East Indies, they encountered different cultures that existed in these territories, which possessed different social structures (more or less complex), where and as a common trait among them, there was a ruling class that held power and determined the destinies of peoples and territories under its control. These elites were those that the Spaniards discovered and conquered in the New World. It was these Spanish conquerors, using European terminology, who correlated the identity of classes of the pre-Hispanic elites, alongside with the royalty or with the nobility of Europe at the time, according to appropriate categories, e.g., emperor, king, etc.[26] The thoughts of the more notable among them give useful insights on how the first European settlers regarded the rulers of Indians in the New World. Fray Bartolome de las Casas, for example, would argue that indigenous nobles were "(...) as Princes and Infantes like those of Castile."[27] Juan de Matienzo, during his rule of Peru, said that the "Caciques, curacas and principales are the native princes of the Indians." In the Lexicon of Fray Domingo de Santo Tomás[28] and Diego González Holguín, as well as in the work of Ludovico Bertonio, several entries included were devoted to identify the pre-Hispanic society, comparing their old titles to those of their counterpart in the Iberian peninsula.[26]

The same approach to the local society in the East Indies was used by the Spaniards.

The principalía was the first estate of the four echelons of Filipino society at the time of contact with Europeans, as described by Fr. Juan de Plasencia, a pioneer Franciscan missionary in the Philippines. Loarca[29](p155) and the Canon Lawyer Antonio de Morga, who classified society into three estates (ruler, ruled, slave), also affirmed the pre‑eminence of the principales.[22](p99) All members of this first estate (the datu class) were principales,[lower-alpha 25] whether they were actually occupying positions to rule, or not. The Real Academia Española defines Principal as a "person or thing that holds first place in value or importance, and is given precedence and preference before others". This Spanish term best describes the first estate of the society in the archipelago, which the Europeans came in contact with. San Buenaventura's 1613 Dictionary of the Tagalog language defines three terms that clarify the concept of this principalía:[22](p99)

- Poon or Punò (chief, leader) – principal or head of a lineage.

- Ginoo – a noble by lineage and parentage, family and descent.

- Maguinoo – principal in lineage or parentage.

The Spanish term Señor (lord) is equated with all these three terms, which are distinguished from the nouveau riche imitators scornfully called maygintao (man with gold or hidalgo by wealth, and not by lineage). The first estate was the class that constituted a birthright aristocracy with claims to respect, obedience, and support from those of subordinate status.[22](p100)

The Local Nobility and the Laws of the Indies

After conquering Manila and making it the capital of the colonial government in 1571, Miguel Lopez de Legaspi noted that aside from the rulers of Cebu and of the capital, the other principales existing in the Archipelago were either heads or Datus of the barangays allied as nations; or tyrants, who were respected only by the law of the strongest. From this system of the law of the strongest sprung intestinal wars, with which certain dominions annihilate one another. Attentive to these existing systems of government, without stripping these ancient sovereigns of their legitimate rights, Legaspi demanded from these local rulers vassalage to the Spanish Crown.[7](p146) Yet, on 11 June 1594, shortly before confirming Legaspi's erection of Manila as a city on 24 June of the same year, [7](p143) King Philip II issued a Royal Decree institutionalizing the recognition of the rights and privileges of the local ruling class of the Philippines, which was later included in the codification of the Recopilación de las leyes de los reynos de Las Indias.

In Book VI, Title VII (dedicated to the caciques) of the Recopilación de las leyes de los reynos de Las Indias, a.k.a. the Laws of the Indies, there are three very interesting laws insofar as they determined the role that the caciques were to play in the Indian new social order under the colonial rule. With these laws, the Spanish Crown officially recognized the rights (of pre-Hispanic origin) of these principales. Specifically, Laws 1, 2 (dedicated to American territories) and; Law 16, instituted by Philip II, on June 11, 1594 (which is similar to the previous two), with the main purpose of assuring that the principales of the Philippines would be treated well and be entrusted with some government charge. Likewise, this provision extended to the Filipino caciques all policies concerning the Indian caciques under the Spanish rule.[lower-alpha 26]

Thus, in order to implement a system of indirect rule in the Philippines, King Philip II ordered, through this law of 11 June 1594, that the honors and privileges of governing, which were previously enjoyed by the local royalty and nobility in formerly sovereign principalities (who later accepted the catholic faith and became subject to him),[lower-alpha 7] should be retained and protected. He also ordered the Spanish governors in the Philippines to treat these native nobles well. The king further ordered that the natives should pay to these nobles the same respect that the inhabitants accorded to their local Lords before the conquest, without prejudice to the things that pertain to the king himself or to the encomenderos.

The royal decree says: "It is not right that the Indian chiefs of Filipinas be in a worse condition after conversion; rather they should have such treatment that would gain their affection and keep them loyal, so that with the spiritual blessings that God has communicated to them by calling them to His true knowledge, the temporal blessings may be added, and they may live contentedly and comfortably. Therefore, we order the governors of those islands to show them good treatment and entrust them, in our name, with the government of the Indians, of whom they were formerly lords. In all else the governors shall see that the chiefs are benefited justly, and the Indians shall pay them something as a recognition, as they did during the period of their paganism, provided this is without prejudice to the tributes that are to be paid us, or to that which pertains to their encomenderos."[30](Libro vi:Título vii; ley xvi)[31]

Through this law, the local Filipino nobles (under the supervision of the Spanish colonial officials) became encomenderos (trustees) also of the King of Spain, who ruled the country indirectly through these nobles. Corollary to this provision, all existing doctrines and laws regarding the Indian caciques were extended to Filipino principales.[lower-alpha 26] Their domains became self‑ruled tributary barangays of the Spanish Empire.[32](p32-33)

The system of indirect government helped in the pacification of the rural areas, and institutionalized the rule and role of an upper class, referred to as the "principalía" or the "principales", until the fall of the Spanish regime in the Philippines in 1898.

The Spanish dominion brought serious modifications to the life and economy of the indigenous society. The shift of emphasis to agriculture marginalized, weakened, and deprived the hildalgo‑like warriors of their significance in the barangays, especially in the trade‑raiding societies in the Visayas (which needed the Viking‑like services of the "timawas"). By the 1580s, many of these noblemen found themselves reduced to leasing land from their datus. Their military functions were eclipsed by farming. Whatever remained would quickly be disoriented, deflected, and destroyed by the superior military power of Spain.[22] (pp117–118)

By the end of the 16th century, any claim to Filipino royalty, nobility or hidalguía had disappeared into a homogenized, Hispanicized and Christianized nobility – the principalía.[22] (p118) This remnant of the pre‑colonial royal and noble families continued to rule their traditional domain until the end of the Spanish regime. However, there were cases when succession in leadership was also done through election of new leaders (cabezas de barangay), especially in provinces near the Manila where the ancient ruling families lost their prestige and role. It appears that proximity to the seat of colonial Government diminished their power and significance. In distant territories, where the central authority had less control and where order could be maintained without using coercive measures, hereditary succession was still enforced, until Spain lost the archipelago to the Americans. These distant territories remained patriarchal societies, where people retained great respect for the principalía.[lower-alpha 27]

The Emergence of the Mestizo Class

The principalía was larger and more influential than the pre‑conquest indigenous nobility. It helped create and perpetuate an oligarchic system in the Spanish colony for more than three hundred years,[1](p331)[13](p218) serving as a link between the Spanish authorities and the local inhabitants.[26]

The Spanish colonial government's prohibition for foreigners to own land in the Philippines contributed to the evolution of this form of oligarchy. In some provinces of the Philippines, many Spaniards and foreign merchants intermarried with the rich and landed Malayo‑Polynesian local nobilities. From these unions, a new cultural group was formed, the mestizo class.[lower-alpha 28] Their descendants emerged later to become an influential part of the government, and of the Principalía.[33]

The increase of population in the Archipelago, as well as the growing presence of Chinese and Mestizos also brought about social changes that necessitated the creation of new members of the principalía for these sectors of Filipino colonial society. [lower-alpha 29][lower-alpha 7] In this regard, pertinent laws were promulgated, such as the above-mentioned royal decree issued on 20 December 1863 (signed in the name of Queen Isabella II by the Minister of the Colonies, José de la Concha), which indicate certain conditions for promotion to the principalía class, among others, the capacity to speak the Castilian language.[lower-alpha 30][lower-alpha 31]

The Royal Cedula of Charles II and the Indigenous Nobles

The emergence of the mestizo class was a social phenomenon not localized in the Philippines, but was also very much present in the American continent. On 22 March 1697, Charles II of Spain issued a Royal Cedula, related to this phenomenon. The Cedula gave distinctions to classes of persons in the social structure of the Crown Colonies, and defined the rights and privileges of colonial functionaries. In doing so, the Spanish Monarch touched another aspect of the colonial society, i.e., the status of indigenous nobles, extending to these indigenous nobles, as well as to their descendants, the preeminence and honors customarily attributed to the Hidalgos of Castile. The Royal Cedula stipulates:

“Bearing in mind the laws and orders issued by my Progenies, Their Majesties the Kings, and by myself, I order the good treatment, assistance, protection and defense of the native Indians of America, that they may be taken cared of, maintained, privileged and honored like all other vassals of my Crown and that, in the course of time, the trial and use of them stops. I feel that its timely implementation is very suitable for public good, for the benefit of the Indians and for the service of God and mine. That, consequently, with respect to the Indian mestizos, the Archbishops and Bishops of the Indias are charged by Article 7, Title VII, Book I of the Laws of the Indies, for ordaining priests, being attentive to the qualities and circumstances present, and if some mestizas ask to be religious, they (Bishops) shall give support to those whom they admit in monasteries and for vows. But in particular, with regard to the requirements for Indians in order to accede to ecclesiastical or secular, governmental, political and military positions, which all require purity of blood and, by its Statute, the condition of nobility, there is distinction between the Indians and mestizos, inasmuch as there is between the [1] descendants of the notable Indians called caciques, and [2] those who are issues of less notable Indian tributaries, who in their pagan state acknowledged vassalage. It is deemed that all preeminence and honors, customarily conferred on the Hijosdalgos of Castile, are to be attributed to the first and to their descendants, both ecclesiastical and secular; and that they can participate in any communities which, by their statutes require nobility; for it is established that these, in their heathenism, were nobles to whom their subordinates acknowledged vassalage and to whom tributes were paid. Such kind of nobility is still retained and acknowledged, keeping these as well as their privileges wherever possible, as recognized and declared by the whole section on the caciques, which is Title VII, Book VI of the Laws of the Indies, wherein for the sake of distinction, the subordinate Indians were placed under (these noble’s) dominion called «cacicazgo», transmissible from elder to elder, to their posteriority…” [9](pp234–235)[lower-alpha 32]

The Royal Cedula was enforced in the Philippines and benefited many indigenous nobles. It can be seen very clearly and irrefutably that, during the colonial period, indigenous chiefs were equated with the Spanish Hidalgos, and the most resounding proof of the application of this comparison is the General Military Archive in Segovia, where the qualifications of “Nobility” (found in the Service Records) are attributed to those Filipinos who were admitted to the Spanish Military Academies and whose ancestors were caciques, encomenderos, notable Tagalogs, chieftains, governors or those who held positions in the municipal administration or government in all different regions of the large islands of the Archipelago, or of the many small islands of which it is composed.[lower-alpha 33] In the context of the ancient tradition and norms of Castilian nobililty, all descendants of a noble are considered noble, regardless of fortune.[34](p4)

At the Real Academia de la Historia, there is also a substantial amount of records giving reference to the Philippine Islands, and while most part corresponds to the history of these islands, the Academia did not exclude among its documents the presence of many genealogical records. The archives of the Academia and its royal stamp recognized the appointments of hundreds of natives of the Philippines who, by virtue of their social position, occupied posts in the administration of the territories and were classified as "Nobles".[lower-alpha 34] The presence of these notables demonstrates the cultural concern of Spain in those Islands to prepare the natives and the collaboration of these in the government of the Archipelago. This aspect of Spanish rule in the Philippines appears much more strongly implemented than in the Americas. Hence in the Philippines, the local Nobility, by reason of charge accorded to their social class, acquired greater importance than in the Indies of the New World.[lower-alpha 35]

The Christianized Filipino Nobles under the Spanish Crown

With the recognition of the Spanish monarchs came the privilege of being addressed as Don or Doña.[lower-alpha 36][2] - a mark of esteem and distinction in Europe reserved for a person of noble or royal status during the colonial period. Other honors and high regard were also accorded to the Christianized Datus by the Spanish Empire. For example, the Gobernadorcillos (elected leader of the Cabezas de Barangay or the Christianized Datus) and Filipino officials of justice received the greatest consideration from the Spanish Crown officials. The colonial officials were under obligation to show them the honor corresponding to their respective duties. They were allowed to sit in the houses of the Spanish Provincial Governors, and in any other places. They were not left to remain standing. It was not permitted for Spanish Parish Priests to treat these Filipino nobles with less consideration.[35](p296-297)

The Gobernadorcillos exercised the command of the towns. They were Port Captains in coastal towns. They also had the rights and powers to elect assistants and several lieutenants and alguaciles, proportionate in number to the inhabitants of the town.[35](p329)

On the day on which the gobernadorcillo would take on government duties, his town would hold a grand celebration. A festive banquet would be offered in the municipal or city hall where he would occupy a seat, adorned by the coat of arms of Spain and with fanciful designs, if his social footing was of a respectable antiquity.[1](pp331–332)[lower-alpha 37]

On holy days the town officials would go to the church, together in one group. The principalía and cuadrilleros (police patrol or assistance) formed two lines in front of the Gobernadorcillo. They would be preceded by a band playing the music as they process towards the church, where the Gobernadorcillo would occupy a seat in precedence among those of the chiefs or cabezas de barangay, who had benches of honor. After the mass, they would usually go to the parish rectory to pay their respects to the parish priest. Then, they would return to the tribunal (municipal hall or city hall) in the same order, and still accompanied by the band playing a loud double quick march called paso doble.[1](p32)

The gobernadorcillo was always accompanied by an alguacil or policia (police officer) whenever he went about the streets of his town.[1](p32)

Certain class symbols

At the later part of the Spanish period, this class of elite Christian landowners started to adopt a characteristic style of dress and carry regalia.[11](p223)[1](p331) They wore a distinctive type of salakot, a Philippine headdress commonly used in the archipelago since the pre‑colonial period. Instead of the usual headgear made of rattan, of reeds called Nitó,[36](p26), or of various shells such as capiz shells, which common Filipinos would wear, the principales would use more prized materials like tortoise shell. The special salakot of the ruling upper class was often adorned with ornate capping spike crafted in metals of value like silver, [37] or, at times, gold.[36](p26) This headgear was usually embossed also with precious metals and sometimes decorated with silver coins or pendants that hung around the rim.[38](Volume 4, pp 1106–1107 'Ethnic Headgear')

It was mentioned earlier that the royalties and nobilities of the Pre-colonial societies in the Visayas, Northern Mindanao, and Luzon (Cebu, Bohol Panay, Mindoro and Manila) also shared the many customs of royalties and nobles in Southeast Asian territories (with Hindu and Buddhist cultures), especially in the generous use of gold and silk in their costumes, as the Boxer Codex demonstrate. The measure of the prince's possession of gold and slaves was proportionate to his greatness and nobility.[39] When the Spaniards reached the shores of the Archipelago, they observed that there was hardly any "Indian" who did not possess chains and other articles of gold.[40]

However, this way of dressing was slowly changed as colonial power took firmer grips of the local nobilities and finally ruled the Islands. By the middle of the 19th century, the Principalía's usual attire was black jacket, European trousers, salakot and colored (velvet) slippers. Many would even wear varnished shoes, such as high quality leather shoes. Their shirt was worn outside the trousers. Some sources say that the Spaniards did not allow the native Filipinos to tuck their shirts under their waistbands, nor were they allowed to have any pockets. It was said that the intention of the colonizers was to remind the natives that they remain indios regardless of the wealth and power they attain. It was a way for discriminating the natives from their Spanish overlords. The locals also used native fabrics of transparent appearance. It is believed that transparent, sheer fabric were mainly for discouraging the Indios from hiding any weapons under their shirts. However, the native nobles did not wish to be outdone in the appearance of their apparel. And so, they richly embroidered their shirts with somewhat baroque designs on delicate Piña fabric. This manner of sporting what originally was a European attire for men led the way to the development of the Barong, which later became the national costume for Filipino men.[41]

Distinctive staffs of office were associated with the Filipino ruling class. The Gobernadorcillo would carry a tassled cane (baston) decorated with precious metals, while his lieutenants would use some kind of wands referred to as "Vara (rama)". On occasions and ceremonies of greater solemnity, they would dress formally in frock coat and high crowned hat.[11](p223)[1](p331)

Questions on Race and Politics, and the Revolution for Independence

Although the principalía had many privileges, there were limitations to how much power they were entitled to under Spanish rule. A member of the principalía could never become the Governor‑General (Gobernador y Capitán General), nor could he become the provincial governor (alcalde mayor).Hypothetically, a member of the principalía could obtain the position of provincial governor if, for example, a noblewoman of the principalía married a Spanish man born in the Philippines (an Insular ) of an elevated social rank. In which case her children would be classified as white (or blanco). However, this did not necessarily give a guarantee that her sons would obtain the position of provincial governor. Being mestizos was not an assurance that they would be loyal enough to the Spanish crown. Such unquestionable allegiance was necessary for the colonizers in retaining control of the archipelago.[11](pp211-225)

The children born of the union between the principales and the insulares, or better still, the peninsulares (a Spanish person born in Spain) are neither assured access to the highest position of power in the colony.[42] Flexibility is known to have occurred in some cases, including that of Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero who even became interim Prime Minister of Spain on August 8, 1897 until October 4 of that same year. Azcárraga also went on to become Prime Minister of Spain again in two more separate terms of office. In 1904, he was granted Knighthood in the very exclusive Spanish chilvalric Order of the Golden Fleece — the only mestizo recipient of this prestigious award.

In the archipelago, however, most often ethnic segregation did put a stop to social mobility, even for members of the principalía – a thing that is normally expected in a colonial rule. It was not also common for principales to be too ambitious so as to pursue very strong desire for obtaining the office of Governor-General. For most part, it appears that the local nobles were inclined to be preoccupied with matters concerning their barangays and towns.[11](pp211-225)

The town mayors received an annual salary of 24 pesos, which was nothing in comparison to the provincial governor's 1,600 pesos and the Governor‑General's 40,000 pesos. Even though the gobernadorcillo's salary was not subject to tax, it was not enough to carry out all the required duties expected of such a position.[11](p223) This explains why among the principales, those who had more wealth were likely to be elected to the office of gobernadorcillo (municipal governor).[1](p326)[16](p294)

Principales tend to marry those who belong to their class, to maintain wealth and power. However, unlike most European royalties who marry their close relatives, e.g. first cousins, for this purpose, Filipino nobles abhorred incestuous unions. In some cases, members of the principalia married wealthy and non‑noble Chinese (Sangley) merchants, who made their fortune in the colony. Principales born of these unions had possibilities to be elected gobernadorcillo by their peers.[33]

Wealth was not the only basis for inter‑marriage between the principales and foreigners, which were commonly prearranged by parents of the bride and groom. Neither did having a Spaniard as one of the parents of a child ennobles him. In a traditionally conservative Catholic environment with Christian mores and norms strictly imposed under the tutelage and prying eyes of Spanish friars,[43](p138)[lower-alpha 38] marriage to a divorcée or secondhand spouse (locally referred to as "tirá ng ibá", literally "others' leftovers") was scornfully disdained by Filipino aristocrats. Virgin brides were a must for the principalía, as well as for the Filipinos in general.

Children who were born outside of marriage, even of Spaniards, were not accepted in the circle of principales. These were severely ostracized in the conservative colonial society and were pejoratively called an "anák sa labás", i.e., "child from outside" (viz., outside marriage), a stigma that still remains part of the contemporary social mores.[44]

During the last years of the regime, there were efforts to push for a representation of the archipelago in the Spanish Cortes among a good number of principales. This move was prevalent especially among those who have studied in Spain and other parts of Europe (Ilustrados). That initiative, however, was met with snobbery by the colonizers, who denied the natives of equal treatment, in any way possible.[45]

Towards the end of the 19th century, civil unrest, which was fuelled by the arrogance, racial discrimination, hypocrisy, and abuses of western colonizers, occurred more frequently. This situation was exposed by the writer and leader of the Propaganda Movement, José Rizal, in his two novels: Noli Me Tángere, and El Filibusterismo (dedicated to the three Filipino Catholic priests, who were executed on 17 February 1872 by Spanish colonial authorities, on charges of subversion arising from the 1872 Cavite mutiny).[46] Because of this growing unrest that turned into an irreversible revolution, the position of provincial governor became awarded more and more often to the peninsulares. In the ecclesiastical sector, a decree was made, stating there were to be no further appointments of Filipinos as parish priests.[11](p107) Nonetheless, nothing that Spain could do was able to retain control over the once submissive subjects, who felt betrayed, among whom were many principales.

Status quaestionis

The recognition of the rights and privileges of the Filipino Principalía as equivalent to those of the Hijosdalgos of Castile appears to facilitate entrance of Filipino nobles into institutions under the Spanish Crown, either civil or religious, which required proofs of nobility. However, such approximation may not be entirely correct since in reality, although the principales were vassals of the Spanish Crown, their rights as sovereign in their former dominions were guaranteed by the Laws of the Indies, more particularly the Royal Decree of Philip II of 11 June 1594, which Charles II confirmed for the purpose stated above, in order to satisfy the requirements of the existing laws in the Peninsula.

From the beginning of the Spanish colonial period, the conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legaspi retained the hereditary rights of the local ancient sovereigns of the Archipelago who vowed allegiance to the Spanish Crown. Many of them accepted the Catholic religion and became Spanish allies at this time. He only demanded from these local rulers vassalage to the Spanish Crown,[lower-alpha 39] replacing the similar overlordship, which previously existed in a few cases, e.g., Sultanate of Brunei's overlordship of the Kingdom of Maynila. Other independent polities, which were not vassals to other States, e.g., Confederation of Madja-as and the Rajahnate of Cebu, were de facto Protectorates/Suzerainties having had alliances with the Spanish Crown before the Kingdom took total control of most parts of the Archipelago.[12](p33)[22](p4)

A question remains after the cessession of Spanish rule in the Philippines regarding any remaining rank equivalency of Filipino Principalía. While no longer vassals of the Spanish crown, they remain unable to exercise their previous sovereignty within the current democratic society in the Philippines. Some believe a logical conclusion would be that ancient Royal and noble titles such as Datu, Lakan, or Apo be retained or re-instituted. These historical titles of local nobles of ancient domains are protected by the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997, and by related international legislation, such as the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Some also believe retaining as subsidiary titles the Hidalguía of Castile, their former protector state, without prejudice to their ancestral title, would be appropriate for the hispanized Filipino nobles. As stated in the Royal Decree of Charles II, the ancient nobility of the Filipino Principales "is still retained and acknowledged".[9](p235)

Besides, the principales retained many of the ordinary obligations of local rulers as manifested in constructing local infrastructures and in maintaining the government offices without funds from Spain. Expenditures of the local government came from the private and personal resources of the principales.[1](p326)[16](p294) Tributes expected of vassals were required of their subjects by their Spanish Crown. These were not taxes that citizens were obliged for financing the government of the Island and for building, developing and maintaining infrastructure in their towns and barangays.[lower-alpha 7] In many ways, the principales retained much of the responsibilities, powers and obligations of the pre-colonial Datus — their predecessors, except for the right to organize their own armed forces. Only the right of Gobernadorcillos to appoint alguacils and "cuadrilleros" (police patrol or assistance) seem to point out to some kind of vestige of this pre-colonial sign of the Datu's coercive power and responsibility to defend his domain.

Like deposed royal families elsewhere in the world, which continue to claim hereditary rights as pretenders to the former thrones of their ancestors, the descendants of the Principalía have similar de iure claims to the historical domains of their forebears.

See also

- Filipino styles and honorifics

- Datu

- Lakan

- Apo (title)

- Maginoo

- Maharlika

- Timawa

- Babaylan

- History of the Philippines (1521–1898)

- Confederation of Madja-as

- Maragtas

- Kingdom of Maynila

- Kingdom of Namayan

- Kingdom of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao

- List of political families in the Philippines

- Gobernadorcillo

- Cabeza de Barangay

Notes

- ↑ In 1893, the Maura Law was passed to reorganize town governments with the aim of making them more effective and autonomous, changing the designation of town leaders from gobernadorcillo to capitan municipal in 1895.

- ↑ Durante la dominación española, el cacique, jefe de un barangay, ejercía funciones judiciales y administrativas. A los tres años tenía el tratamiento de don y se reconocía capacidad para ser gobernadorcillo, con facultades para nombrarse un auxiliar llamado primogenito, siendo hereditario el cargo de jefe.[2](p624)

- ↑ Article 16 of the Royal Decree of 20 December 1863 says: After a school has been established in any village for fifteen years, no natives who cannot speak, read and write the Castilian language shall form part of the Principalía unless they enjoy that distinction by right of inheritance. After the school has been established for thirty years, only those who possess the above‑mentioned condition shall enjoy exemption from the personal service tax, except in the case of the sick. Isabel II[3](p85)

- ↑ The royal decree was implemented in the Philippines by the Governor‑General through a circular signed on 30 August 1867. Section III of the circular says: The law has considered them very carefully and it is fitting for the supervisor to unfold before the eyes of the parents so that their simple intelligence may well understand that not only ought they, but that it is profitable for them to send their children to school, for after the schools have been established for fifteen years in the village of their tribes those who cannot speak, read, or write Castilian: cannot be gobernadorcillos; nor lieutenants of justice; nor form part of the principalía; unless they enjoy that privilege because of heredity... General Gándara, Circular of the Superior Civil Government Giving Rules for the Good Discharge of School Supervision[3](p133)

- ↑ The increase of population during the colonial period consequently needed the creation of new leaders, with this quality. The emergence of the mestizo culture (both Filipinos of Spanish descent and Filipinos of Chinese descent) had also necessitated this, and even the subsequent designation of separate institutions or offices of gobernadorcillos for the different mestizo groups and for the indigenous tribes living in the same territories or cities with large population.[1](pp324–326)

- ↑ The cabezas, their wives, and first‑born sons enjoyed exemption from the payment of tribute to the Spanish crown.[5](p326)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 L'institution des chefs de barangay a été empruntée aux Indiens chez qui on la trouvée établie lors de la conquête des Philippines; ils formaient, à cette époque une espèce de noblesse héréditaire. L'hérédité leur a été conservée aujourd hui: quand une de ces places devient vacante, la nomination du successeur est faite par le surintendant des finances dans les pueblos qui environnent la capitale, et, dans les provinces éloignées, par l'alcalde, sur la proposition du gobernadorcillo et la présentation des autres membres du barangay; il en est de même pour les nouvelles créations que nécessite de temps à autre l'augmentation de la population. Le cabeza, sa femme et l'aîné de ses enfants sont exempts du tributo[8](p356)

- ↑ Esta institucion (Cabecería de Barangay), mucho más antigua que la sujecion de las islas al Gobierno, ha merecido siempre las mayores atencion. En un principio eran las cabecerías hereditarias, y constituian la verdadera hidalguía del país; mas del dia, si bien en algunas provincias todavía se tramiten por sucesion hereditaria, las hay tambien eleccion, particularmente en las provincias más inmediatas á Manila, en donde han perdido su prestigio y son una verdadera carga. En las provincias distantes todavía se hacen respetar, y allí es precisamente en donde la autoridad tiene ménos que hacer, y el órden se conserva sin necesidad de medidas coercitivas; porque todavía existe en ellas el gobierno patriarcal, por el gran respeto que la plebe conserva aún á lo que llaman aquí principalía.[7](p61)

- ↑ "There were no kings or lords throughout these islands who ruled over them as in the manner of our kingdoms and provinces; but in every island, and in each province of it, many chiefs were recognized by the natives themselves. Some were more powerful than others, and each one had his followers and subjects, by districts and families; and these obeyed and respected the chief. Some chiefs had friendship and communication with others, and at times wars and quarrels. These principalities and lordships were inherited in the male line and by succession of father and son and their descendants. If these were lacking, then their brothers and collateral relatives succeeded... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay."[12](Chapter VIII)

- ↑ Por otra parte, mientras en las Indias la cultura precolombiana había alcanzado un alto nivel, en Filipinas la civilización isleña continuaba manifestándose en sus estados más primitivos. Sin embargo, esas sociedades primitivas, independientes totalmente las unas de las otras, estaban en cierta manera estructuradas y se apreciaba en ellas una organización jerárquica embrionaria y local, pero era digna de ser atendida. Precisamente en esa organización local es, como siempre, de donde nace la nobleza. El indio aborigen, jefe de tribu, es reconocido como noble y las pruebas irrefutables de su nobleza se encuentran principalmente en las Hojas de Servicios de los militares de origen filipino que abrazaron la carrera de las Armas, cuando para hacerlo necesariamente era preciso demostrar el origen nobiliario del individuo.[9](p232)

- ↑ Durante la dominación española, el cacique, jefe de un barangay, ejercía funciones judiciales y administrativas. A los tres años tenía el tratamiento de don y se reconocía capacidad para ser gobernadorcillo.[2](p624)

- ↑ "También en este sector, el uso de las palabras doña y don se limito estrechamente a vecinas y vecinos distinguidos."[15](p114)

- ↑ There was only a very small standing army to protect the Spanish government in the Philippines. This ridiculous situation made an old viceroy of New Spain say: "En cada fraile tenía el Rey en Filipinas un capitán general y un ejército entero." ("In each friar in the Philippines the King had a captain general and a whole army.")[8](p389)

- ↑ "Of little avail would have been the valor and constancy with which Legaspi and his worthy companions overcame the natives of the islands, if the apostolic zeal of the missionaries had not seconded their exertions, and aided to consolidate the enterprise. The latter were the real conquerors; they who without any other arms than their virtues, gained over the good will of the islanders, caused the Spanish name to be beloved, and gave the king, as it were by a miracle, two millions more of submissive and Christian subjects."[17](p209)

- ↑ "C'est par la seule influence de la religion que l'on a conquis les Philippines, et cette influence pourra seule les conserver." ("It is only by the influence of religion that Philippines was conquered. Only this influence could keep them.")[8](p40)

- ↑ The American Era in the Philippines provides a unique opportunity to explore concepts that shaped American imperialism. The nature of imperialism in the Philippines is understood not only in the policy decisions of governments but also in the experience of particular social groups who lived there. Therefore, this study emphasizes the cultural and economic interchange between American colonists and Filipinos from 1901 until 1940. American colonialism in the Philippines fostered complex cultural relationships as seen through individual identity. To some extent Americans developed a transnational worldview by living within the Philippines while maintaining connections to America. Filipinos viewed American colonialism from the perspective of their Spanish traditions, a facet often undervalued by the new regime... Many Americans who lived in the Islands engaged in commerce. Trade served as a natural domain for foreigners as it had over the centuries. Filipinos retained ownership of large tracts of the countryside supported by Washington's policies that limited American investments, especially through tariff structures. The emphasis on business in the Islands followed a broader trend during the 1920s of rejecting progressive regulation in favor of the free market. These men and women developed a mentality of Americans in the Philippines, an important distinction. They lived in the Islands while confining social contacts to their peers by means of restrictive clubs and associations.[19](pAbstract)

- ↑ For more information regarding the social system in barangays of the Indigenous Philippine society before the Spanish colonization, see Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana, Vol. VII.[2](p624) The article also says: Los nobles de un barangay eran los más ricos ó los más fuertes, formándose por este sistema los dattos ó maguinoos, principes á quienes heredaban los hijos mayores, las hijas á falta de éstos, ó los parientes más próximos si no tenían descendencia directa; pero siempre teniendo en cuenta las condiciones de fuerza ó de dinero...Los vassalos plebeyos tenían que remar en los barcos del maguinoo, cultivar sus campos y pelear en la guerra. Los siervos, que formaban el término medio entre los esclavos y los hombres libres, podían tener propriedad individual, mujer, campos, casa y esclavos; pero los tagalos debían pagar una cantidad en polvo de oro equivalente á una parte de sus cosechas, los de los barangayes bisayas estaban obligados á trabajar en las tieras del señor cinco días al mes, pagarle un tributo anual en arroz y hacerle un presente en las fiestas. Durante la dominación española, el cacique, jefe de un barangay, ejercía funciones judiciales y administrativas. A los tres años tenía el tratamiento de don y se reconocía capacidad para ser gobernadorcillo, con facultades para nombrarse un auxiliar llamado primogenito, siendo hereditario el cargo de jefe.

- ↑ It should also be noted that the more popular and official term used to refer to the leaders of the district or to the cacique during the Spanish period was Cabeza de Barangay.

- ↑ In Panay, the existence of highly developed and independent principalities of Ogtong (Oton) and that of Araut (Dumangas) were well known to early Spanish settlers in the Philippines. The Augustinian historian Gaspar de San Agustin, for example, wrote about the existence of an ancient and illustrious nobility in Araut, in his book he said: "También fundó convento el Padre Fray Martin de Rada en Araut – que ahora se llama el convento de Dumangas – con la advocación de nuestro Padre San Agustín...Está fundado este pueblo casi a los fines del río de Halaur, que naciendo en unos altos montes en el centro de esta isla (Panay)...Es el pueblo muy hermoso, ameno y muy lleno de palmares de cocos. Antiguamente era el emporio y corte de la más lucida nobleza de toda aquella isla."[20](pp374–375)

- ↑ "There were no kings or lords throughout these islands who ruled over them as in the manner of our kingdoms and provinces; but in every island, and in each province of it, many chiefs were recognized by the natives themselves. Some were more powerful than others, and each one had his followers and subjects, by districts and families; and these obeyed and respected the chief. Some chiefs had friendship and communication with others, and at times wars and quarrels. These principalities and lordships were inherited in the male line and by succession of father and son and their descendants. If these were lacking, then their brothers and collateral relatives succeeded... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay."[12](Chapter VIII)

- ↑ Historians classify four types of unHispanicized societies in the Philippines, some of which still survive in remote and isolated parts of the country: Classless societies; Warrior societies: characterized by a distinct warrior class, in which membership is won by personal achievement, entails privilege, duty and prescribed norms of conduct, and is requisite for community leadership; Petty Plutocracies: which are dominated socially and politically by a recognized class of rich men who attain membership through birthright, property and the performance of specified ceremonies. They are "petty" because their authority is localized, being extended by neither absentee landlordism nor territorial subjugation; Principalities:[22](p139)

- ↑ "En las Visayas ayudaba siempre a los amigos, y sujetaba solamente con las armas a los que los ofendian, y aun despues de subyugados no les exigia mas que un reconocimiento en especie, a que se obligan. " ("In the Visayas [Legaspi] always helped friends, and wield weapons only against those who offended them (his friends), and even after he subjugated them (those who offended his friends), he did not demand more than some kind of acknowledgment from those whom he conquered.")[7](p146)

- ↑ The word "sakop" means "jurisdiction", and "Kinadatuan" refers to the realm of the Datu - his principality.

- ↑ In Panay, even at present, the landed descendants of the principales are still referred to as agalon or amo by their tenants. However, the tenants are no longer called oripun (in Karay‑a, i.e., the Ilonggo sub‑dialect) or olipun (in Sinâ, i.e., Ilonggo spoken in the lowlands and cities). Instead, the tenants are now commonly referred to as tinawo (subjects).

- ↑ Tous les descendants de ces chefs étaient regardés comme nobles et exempts des corvées et autres services auxquels étaient assujettis les roturiers que l'on appelait "timaguas". Les femmes étaient nobles comme les hommes.[8](p53)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 En el Título VII, del Libro VI, de la Recopilación de las leyes de los reynos de Las Indias, dedicado a los caciques, podemos encontrar tres leyes muy interesantes en tanto en cuanto determinaron el papel que los caciques iban a desempeñar en el nuevo ordenamiento social indiano. Con ellas, la Corona reconocía oficialmente los derechos de origen prehispánico de estos principales. Concretamente, nos estamos refiriendo a las Leyes 1, 2, dedicadas al espacio americano . Y a la Ley 16, instituida por Felipe II el 11 de junio de 1594 -a similitud de las anteriores-, con la finalidad de que los indios principales de las islas Filipinas fuesen bien tratados y se les encargase alguna tarea de gobierno. Igualmente, esta disposición hacía extensible a los caciques filipinos toda la doctrina vigente en relación con los caciques indianos...Los principales pasaron así a formar parte del sistema político-administrativo indiano, sirviendo de nexo de unión entre las autoridades españolas y la población indígena. Para una mejor administración de la precitada población, se crearon los «pueblos de indios» -donde se redujo a la anteriormente dispersa población aborigen-.[26]

- ↑ Esta institucion (Cabecería de Barangay), mucho más antigua que la sujecion de las islas al Gobierno, ha merecido siempre las mayores atencion. En un principio eran las cabecerías hereditarias, y constituian la verdadera hidalguía del país; mas del dia, si bien en algunas provincias todavía se tramiten por sucesion hereditaria, las hay tambien eleccion, particularmente en las provincias más inmediatas á Manila, en donde han perdido su prestigio y son una verdadera carga. En las provincias distantes todavía se hacen respetar, y allí es precisamente en donde la autoridad tiene ménos que hacer, y el órden se conserva sin necesidad de medidas coercitivas; porque todavía existe en ellas el gobierno patriarcal, por el gran respeto que la plebe conserva aún á lo que llaman aquí principalía.[7](p61)

- ↑ also v.encomienda; hacienda

- ↑ (The creation of new principales, i.e., cabezas de barangay, was done by the Superintendent of Finance in cases of those towns near Manila. For those in distant provinces, the alcaldes named the new leader, proposed by the gobernadorcillo of the town where the barangay is located. The candidate proposed by the gobernadorcillo is the person presented by the members of the barangay.)

- ↑ Article 16 of the Royal Decree of 20 December 1863 says: After a school has been established in any village for fifteen years, no natives who cannot speak, read and write the Castilian language shall form part of the principalía unless they enjoy that distinction by right of inheritance. After the school has been established for thirty years, only those who possess the above‑mentioned condition shall enjoy exemption from the personal service tax, except in the case of the sick. Isabel II[3](p85)

- ↑ The royal decree was implemented in the Philippines by the Governor‑General through a circular signed on 30 August 1867. Section III of the circular says: The law has considered them very carefully and it is fitting for the supervisor to unfold before the eyes of the parents so that their simple intelligence may well understand that not only ought they, but that it is profitable for them to send their children to school, for after the schools have been established for fifteen years in the village of their tribes those who cannot speak, read, or write Castilian: cannot be gobernadorcillos; nor lieutenants of justice; nor form part of the principalía; unless they enjoy that privilege because of heredity... General Gándara, Circular of the Superior Civil Government Giving Rules for the Good Discharge of School Supervision[3](p133)

- ↑ Por cuanto teniendo presentes las leyes y cédulas que se mandaron despachar por los Señores Reyes mis progenitores y por mí, encargo el buen tratamiento, amparo, protección y defensa de los indios naturales de la América, y que sean atendidos, mantenidos, favorecidos y honrados como todos los demás vasallos de mi Corona, y que por el trascurso del tiempo se detiene la práctica y uso de ellas, y siento tan conveniente su puntual cumplimiento al bien público y utilidad de los Indios y al servicio de Dios y mío, y que en esta consecuencia por lo que toca a los indios mestizos está encargo a los Arzobispos y Obispos de las Indias, por la Ley Siete, Título Siete, del Libro Primero, de la Recopilación, los ordenen de sacerdotes, concurriendo las calidades y circunstancias que en ella se disponen y que si algunas mestizas quisieren ser religiosas dispongan el que se las admita en los monasterios y a las profesiones, y aunque en lo especial de que quedan ascender los indios a puestos eclesiásticos o seculares, gubernativos, políticos y de guerra, que todos piden limpieza de sangre y por estatuto la calidad de nobles, hay distinción entre los Indios y mestizos, o como descendentes de los indios principales que se llaman caciques, o como procedidos de indios menos principales que son los tributarios, y que en su gentilidad reconocieron vasallaje, se considera que a los primeros y sus descendentes se les deben todas las preeminencias y honores, así en lo eclesiástico como en lo secular que se acostumbran conferir a los nobles Hijosdalgo de Castilla y pueden participar de cualesquier comunidades que por estatuto pidan nobleza, pues es constante que estos en su gentilismo eran nobles a quienes sus inferiores reconocían vasallaje y tributaban, cuya especie de nobleza todavía se les conserva y considera, guardándoles en lo posible, o privilegios, como así se reconoce y declara por todo el Título de los caciques, que es el Siete, del Libro Seis, de la Recopilación, donde por distinción de los indios inferiores se les dejó el señorío con nombre de cacicazgo, transmisible de mayor en mayor, a sus posterioridades...

- ↑ Por ella se aprecia bien claramente y de manera fehaciente que a los caciques indígenas se les equiparada a los Hidalgos españoles y la prueba más rotunda de su aplicación se halla en el Archivo General Militar de Segovia, en donde las calificaciones de «Nobleza» se encuentran en las Hojas de Servicio de aquellos filipinos que ingresaron en nuestras Academias Militares y cuyos ascendientes eran caciques, encomenderos, tagalos notables, pedáneos, por los gobernadores o que ocupan cargos en la Administración municipal o en la del Gobierno, de todas las diferentes regiones de las grandes islas del Archipiélago o en las múltiples islas pequeñas de que se compone el mismo.[9](p235)

- ↑ Por otra parte, mientras en las Indias la cultura precolombiana había alcanzado un alto nivel, en Filipinas la civilización isleña continuaba manifestándose en sus estados más primitivos. Sin embargo, esas sociedades primitivas, independientes totalmente las unas de las otras, estaban en cierta manera estructuradas y se apreciaba en ellas una organización jerárquica embrionaria y local, pero era digna de ser atendida. Precisamente en esa organización local es, como siempre, de donde nace la nobleza. El indio aborigen, jefe de tribu, es reconocido como noble y las pruebas irrefutables de su nobleza se encuentran principalmente en las Hojas de Servicios de los militares de origen filipino que abrazaron la carrera de las Armas, cuando para hacerlo necesariamente era preciso demostrar el origen nobiliario del individuo.[9](p232)

- ↑ También en la Real Academia de la Historia existe un importante fondo relativo a las Islas Filipinas, y aunque su mayor parte debe corresponder a la Historia de ellas, no es excluir que entre su documentación aparezcan muchos antecedentes genealógicos… El Archivo del Palacio y en su Real Estampilla se recogen los nombramientos de centenares de aborígenes de aquel Archipiélago, a los cuales, en virtud de su posición social, ocuparon cargos en la administración de aquellos territorios y cuya presencia demuestra la inquietud cultural de nuestra Patria en aquéllas Islas para la preparación de sus naturales y la colaboración de estos en las tareas de su Gobierno. Esta faceta en Filipinas aparece mucho más actuada que en el continente americano y de ahí que en Filipinas la Nobleza de cargo adquiera mayor importancia que en las Indias.[9](p234)

- ↑ Durante la dominación española, el cacique, jefe de un barangay, ejercía funciones judiciales y administrativas. A los tres años tenía el tratamiento de don y se reconocía capacidad para ser gobernadorcillo.[2](p624)

- ↑ The fanciful designs referred to by Blair and Robertson hint of the existence of some family symbols of the Datu Class, which existed before the Spanish conquest of the islands. Unfortunately, there has been no study of these symbols, which might be equivalent to what heraldry is in western countries.

- ↑ "The question of the validity of marriages performed by other persons than the parish priests has been much discussed in the Philippines. There have been many marriages of American citizens between themselves and of Americans to Spanish and Filipino women. The subject is of vast importance, involving, as it does, the legitimacy of issue and the validity of marriage. The law of marriage in the Philippines is a canonical law and nothing else. When a man wishes to get married he goes to the parish priest and the parish priest examines the woman and finds out whether she wishes to marry the man and what her race is - whether Spanish, Mestizo, Chinese, or any other - and then ascertains whether the fathers of both parties are willing that the marriage should be solemnized. The law which is in force in Spain and also in the Philippines in regard to marriages of natives, Spaniards, and Spanish half- castes, is that they can not marry without the consent of their parents or family unless they are 23 years of age; but this is not true in the case of Chinese Mestizos, who can marry at the age of 16 without the family's consent. This applies to both sexes. This privilege of the Mestizo Chinese, which was granted by the Pope had this object in view: The increase of this race, which is the race considered to be the most industrious. The priest then finds out if there is any impediment to the marriage and if he finds none he calls the banns openly in the church for three Sundays, and if no one makes any objection to the marriage the contractants are allowed to marry on the day following the third Sunday."

- ↑ "En las Visayas ayudaba siempre a los amigos, y sujetaba solamente con las armas a los que los ofendian, y aun despues de subyugados no les exigia mas que un reconocimiento en especie, a que se obligan. " English translation: "In the Visayas [Legaspi] always helped friends, and wield weapons only against those who offended them (his friends), and even after he subjugated them (those who offended his friends), he did not demand more than some kind of acknowledgment from those whom he conquered."[7](p146)

Further reading

- Luque Talaván, Miguel, Análisis Histórico-Jurídico de la Nobleza Indiana de Origen Prehispánico (Conferencia en la Escuela «Marqués de Aviles» de Genealogía, Heráldica y Nobiliaria de la «Asociación de Diplomados en Genealogía, Heráldica y Nobiliaria»).[26]

- Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent, Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de «Hidalguia», 1953-1993: 40 años de un pensamiento, Madrid: 1993, Graficas Ariás Montano, S.A.-MONTOLES, pp. 232–235.[9][8][8][8][8][8]

- Regalado Trota Jose, The Many Images of Christ (particularly in the section: Spain retains the old class system) in DALISAY, Jose Y, ed. (1998), Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People.[47](Vol 3, pp 178–179)

- See also: Alfredo Reyes; CORDERO-FERNANDO, Gilda; QUIRINO, Carlos & GUTIERREZ, Manuel C, eds. Filipino Heritage: the Making of a Nation (10 vols), Manila: 1997, Lahing Pilipino Publications.[38](Volume 5, pp1155–1158: 'The Ruling Class')

- Celdrán Ruano, Julia, ed. (2009). La configuración del sistema jurídico hispano en las Islas Filipinas: orígenes y evolución (siglos XVI-XVIII) in Anales de Derecho, Vol. 27 (2009) (pdf) (in Español).

- Jorge Alberto Liria Rodríguez, LA PECULIAR ADMINISTRACIÓNESPAÑOLA EN FILIPINAS (1890-1898), Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Anroart, Asociación canaria para la difusión de la cultura y el arte , 2004.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds (1904). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 17 of 55 (1609–1616). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE; additional translations by Henry B. Lathrop. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-1426486869. OCLC 769945708. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/15530. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana. VII. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S.A.. 1921.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds (1907). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 46 of 55 (1721–1739). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. OCLC 769944922. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/philamer/afk2830.0001.046. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century."

- ↑ José de la Concha, El ministro de Ultramar. "Real Decreto" (in Spanish) (pdf). Gaceta de Madrid. https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE/1863/358/A00001-00002.pdf.

- ↑ BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 42 of 55 (1670–1700). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE;. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-1103955435. OCLC 769945732. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/34384. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century."

- ↑ The original manuscript of the report of R.P. Fray Bernardo Arquero, O.S.A., dated 1 January 1897, on the statistical data and historical information of the Parish of St. John the Baptist in Banate, Iloilo (Philippines). The first column of the document (Personas con Cedula Personal) identifies the classes of citizens of the town: the "de privilegio y gratis" (principales) and the "de pago". This document can be found in the Archives of the Monastery of the Augustinian Province of the Most Holy Name of Jesus of the Philippines in Valladolid, Spain.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 FERRANDO, Fr Juan & FONSECA OSA, Fr Joaquin (1870–1872) (in Spanish). Historia de los PP. Dominicos en las Islas Filipinas y en las Misiones del Japon, China, Tung-kin y Formosa (Vol. 1 of 6 vols). Madrid: Imprenta y esteriotipia de M Rivadeneyra. OCLC 9362749. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/9362749.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 MALLAT de BASSILAU, Jean (1846) (in French). Les Philippines: Histoire, géographie, moeurs. Agriculture, industrie et commerce des Colonies espagnoles dans l'Océanie (2 vols). Paris: Arthus Bertrand Éd.. ISBN 978-1143901140. OCLC 23424678. https://archive.org/details/lesphilippinesh00mallgoog.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 DE CADENAS Y VICENT, Vicente (1993) (in Spanish). Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de "Hidalguia", 1953-1993: 40 años de un pensamiento. Madrid: HIDALGUIA. ISBN 9788487204548. https://books.google.com/books?id=MUZiJ2XG_-IC&lpg=PA232&ots=XtW6Qoc86n&dq=Vicente%20de%20Cadenas%20y%20Vicent%2C%20Las%20Pruebas%20de%20Nobleza%20y%20Genealogia%20en%20Filipinas%20y%20Los%20Archivios%20en%20Donde%20se%20Pueden%20Encontrar%20Antecedentes%20de%20Ellas%20in%20Heraldica%2C%20Genealogia%20y%20Nobleza%20en%20los%20Editoriales%20de%20%C2%ABHidalguia%C2%BB%2C&hl=it&pg=PA28#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ de los Reyes, Isabelo, ed (1889) (in Español) (Book). Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición). Manila: Tipo-Litografia de Chofré y C.a. https://archive.org/details/lasislasvisayase00reye.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Foreman, John, ed (1907) (in English) (book). The Philippine Islands : a political, geographical, ethnographical, social and commercial history of the Philippine Archipelago, embracing the whole period of Spanish rule, with an account of the succeeding American insular government.. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. https://archive.org/details/island00forephilippinerich.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds (1904) (in Spanish). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 15 of 55 (1609). Completely translated into English and annotated by the editors. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-1231213940. OCLC 769945706. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century. — From their discovery by Magellan in 1521 to the beginning of the XVII Century; with descriptions of Japan, China and adjacent countries, by Dr. ANTONIO DE MORGA Alcalde of Criminal Causes, in the Royal Audiencia of Nueva Espana, and Counsel for the Holy Office of the Inquisition."

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 40 of 55 (1690–1691). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE;. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0559361821. OCLC 769945730. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/30253. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century."

- ↑ An example of a document pertaining to the Spanish colonial government mentioning the "vecinos distinguidos" is the 1911 Report written by R. P. Fray Agapito Lope, O.S.A. (parish priest of Banate, Iloilo in 1893) on the state of the Parish of St. John the Baptist in this town in the Philippines. The second page identifies the "vecinos distinguidos" of the Banate during the last years of the Spanish rule. The original document is in the custody of the Monastery of the Augustinian Province of the Most Holy Name of Jesus of the Philippines in Valladolid, Spain . Cf. Fray Agapito Lope 1911 Manuscript, p. 1. Also cf. Fray Agapito Lope 1911 Manuscript, p. 2.

- ↑ BERND SCHRÖTER and CHRISTIAN BÜSCHGES, ed (1999) (in Español) (book). Beneméritos, aristócratas y empresarios: Identidades y estructuras sociales de las capas altas urbanas en América hispánica.. Frankfurt; Madrid: Vervuert Verlag; Iberoamericana.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 ZAIDE, Gregorio F (1979). The Pageant of Philippine History: Political, economic, and socio-cultural. Philippine Education Company.

- ↑ de COMYN, Tomas (1821) [1810]. Estado de las islas Filipinas en 1810. Translated from Spanish with notes and a preliminary discourse by William Walton 1821. London: T. and J. Allman. 645339. OCLC 10569141. http://dlxs.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=sea;cc=sea;view=toc;subview=short;idno=sea225.

- ↑ Liria Rodríguez, Jorge Alberto, ed (1998) (in Español) (pdf). 1890. La peculiar administración española en Filipinas in XIII Coloquio de historia canario - americano, Coloquio 13. https://mdc.ulpgc.es/cdm/ref/collection/coloquios/id/820.

- ↑ KASPERSKI, Kenneth F. (2012). Noble colonials: Americans and Filipinos, 1901--1940 (Ph.D. Dissertation/Thesis: University of Florida). Ann Arbor: ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing. ISBN 9781267712370. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1086350649.

- ↑ de SAN AGUSTIN OSA (1650–1724), Fr Gaspár; DIAZ OSA, Fr Casimiro (1698) (in Spanish). Conquistas de las Islas Philipinas. Parte primera : la temporal, por las armas del señor don Phelipe Segundo el Prudente, y la espiritual, por los religiosos del Orden de Nuestro Padre San Augustin; fundacion y progreso de su Provincia del Santissimo Nombre de Jesus. Madrid: Imprenta de Manuel Ruiz de Murga. ISBN 978-8400040727. OCLC 79696350. " The second part of the work, compiled by Casimiro Díaz Toledano from the manuscript left by Gaspár de San Agustín, was not published until 1890 under the title: Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas, Parte segunda."

- ↑ Manuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Madrid 1975.

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 22.12 22.13 SCOTT, William Henry (1982). Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-9711000004. OCLC 9259667.

- ↑ Seclusion and Veiling of Women: A Historical and Cultural Approach