Biology:Chimeric antigen receptor

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs, also known as chimeric immunoreceptors, chimeric T cell receptors or artificial T cell receptors) are receptor proteins that have been engineered to give T cells the new ability to target a specific protein. The receptors are chimeric because they combine both antigen-binding and T-cell activating functions into a single receptor.

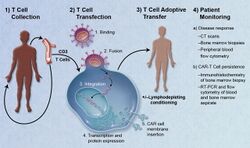

CAR-T cell therapy uses T cells engineered with CARs for cancer therapy. The premise of CAR-T immunotherapy is to modify T cells to recognize cancer cells in order to more effectively target and destroy them. Scientists harvest T cells from people, genetically alter them, then infuse the resulting CAR-T cells into patients to attack their tumors.[1] CAR-T cells can be either derived from T cells in a patient's own blood (autologous) or derived from the T cells of another healthy donor (allogenic). Once isolated from a person, these T cells are genetically engineered to express a specific CAR, which programs them to target an antigen that is present on the surface of tumors. For safety, CAR-T cells are engineered to be specific to an antigen expressed on a tumor that is not expressed on healthy cells.[2]

After CAR-T cells are infused into a patient, they act as a "living drug" against cancer cells.[3] When they come in contact with their targeted antigen on a cell, CAR-T cells bind to it and become activated, then proceed to proliferate and become cytotoxic.[4] CAR-T cells destroy cells through several mechanisms, including extensive stimulated cell proliferation, increasing the degree to which they are toxic to other living cells (cytotoxicity), and by causing the increased secretion of factors that can affect other cells such as cytokines, interleukins, and growth factors.[5]

Use in cancer

1. T-cells (represented by objects labeled as ’t’) are removed from the patient's blood.

2. Then in a lab setting the gene that encodes for the specific antigen receptors are incorporated into the T-cells.

3. Thus producing the CAR receptors (labeled as c) on the surface of the cells.

4. The newly modified T-cells are then further harvested and grown in the lab.

5. After a certain time period, the engineered T-cells are infused back into the patient.

Adoptive transfer of T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors is a promising anti-cancer therapeutic as CAR-modified T cells can be engineered to target virtually any tumor associated antigen. There is great potential for this approach to improve patient-specific cancer therapy in a profound way. Following collection of a patient's T cells, the cells are genetically engineered to express CARs specifically directed toward antigens on the patient's tumor cells, then infused back into the patient.[6]

Preparation

The first step in the introduction of CAR-T cells into the body of a patient is the removal of activated leukocytes from the blood in a process known as leukocyte apheresis. The leukocytes are removed using a blood cell separator. The patient’s autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are then separated and collected from the buffy coat that forms.[7] The products of leukocyte apheresis are then transferred into a cell processing center. In the cell processing centre, specific T-cells are activated in a certain environment in which they can actively proliferate. The cells are activated using a type of cytokine called an interleukin, specifically Inter-Leukin 2 (IL-2) as well as anti-CD3 antibodies.[8]

The T-cells are then transfected with CD19 CAR genes by either an integrating gammaretrovirus (RV) or by lentivirus (LV) vectors. These vectors are very safe in modern times due to a partial deletion of the U3 region.[9] The patient undergoes lymphodepletion chemotherapy prior to the introduction of the engineered CD CAR-T cells.[10] The depletion of the number of circulating leukocytes in the patient upregulates the number of cytokines that are produced which help to promote the expansion of the engineered CAR-T cell.[11]

Safety concerns

CAR-T cells are undoubtedly a major breakthrough in cancer treatment. However, there are still expected and unexpected toxicities that result from CAR-T cells being introduced into the body. These toxicities include cytokine release syndrome, neurological toxicity, on-target/off-tumor recognition, insertional mutagenesis, and anaphylaxis.[10]

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is a condition in which the immune system is activated and releases an increased number of inflammatory cytokines. The clinical manifestations of this syndrome include high fever, fatigue, myalgia, nausea, tachycardia, capillary leakages, cardiac dysfunction, hepatic failure, and renal impairment.[12]

The neurological toxicity associated with CAR-T cells have clinical manifestations that include delirium, the partial loss of the ability to speak a coherent language while still having the ability to interpret language (expressive aphasia), lowered alertness (obtundation), and seizures.[13] During some clinical trials deaths caused by neurotoxicity have occurred. The main cause of death from neurotoxicity is cerebral edema. In a study carried out by Juno Therapeutics, Inc., five patients enrolled in the trial died as a result of cerebral edema. Two of the patients were treated with cyclophosphamide alone and the remaining three were treated with a combination of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine.[14] In another clinical trial sponsored by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, there was one reported case of irreversible and fatal neurological toxicity 122 days after the administration of CAR-T cells.[15]

On-target/off-tumor recognition occurs when the CAR-T cell recognizes the correct antigen, but the antigen is expressed on healthy, non-pathogenic tissue. This results in the CAR-T cells attacking non-tumor tissue, such as healthy B cells that express CD19. The severity of this adverse effect can vary from B-cell aplasia to extreme toxicity leading to death.[8]

Anaphylaxis is an expected side effect, as the CAR is made with a foreign monoclonal antibody and as a result, invokes an immune response.

There is also a potential for insertional mutagenesis, which can occur when using a virus to insert the CAR vector DNA into a host T cell. Lentiviral (LV) vectors carry a lower risk than retroviral (RV) vectors. However, both have the potential to be oncogenic.

Because it is a relatively new treatment, there is little data about the long-term effects of CAR-T cell therapy. There are still concerns about long-term survival as well as pregnancy complications in female patients treated with CAR-T cells.[13]

Structure

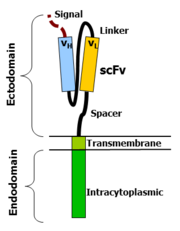

CAR-T cells create a link between an extracellular ligand recognition domain to an intracellular signalling molecule which in turn activates T cells. The extracellular ligand recognition domain is usually a single-chain variable fragment (scFv). CARs are composed of three regions: the ectodomain, the transmembrane domain and the endodomain.

Ectodomain

The ectodomain is the region of the receptor that is exposed to the extracellular fluid and consists of 3 components: a signalling peptide, an antigen recognition region and a spacer.

A signal peptide directs the nascent protein into the endoplasmic reticulum. The signal protein in CAR is called a single-chain variable fragment (scFv),[16] a type of protein known as a fusion protein or chimeric protein. A fusion protein is a protein that is formed by merging two or more genes that code originally for different proteins but when they are translated in the cell, the translation produces one or more polypeptides with functional properties derived for each of the original genes.[17]

A scFv is a chimeric protein made up of the light and heavy chains of immunoglobins connected with a short linker peptide. The linker consists of hydrophilic residues with stretches of glycine and serine in it for flexibility as well as stretches of glutamate and lysine for added solubility.[18]

Transmembrane domain

The transmembrane domain is a hydrophobic alpha helix that spans the membrane. The transmembrane domain is essential for the stability of the receptor as a whole. At present, the CD28 transmembrane domain is the most stable of the domains.

Generally, the transmembrane domain from the most membrane proximal component of the endodomain is used. Using the CD3-zeta transmembrane domain may result in incorporation of the artificial TCR into the native TCR, a factor that is dependent on the presence of the native CD3-zeta transmembrane charged aspartic acid residue.[19] Different transmembrane domains result in different receptor stability. The CD28 transmembrane domain results in a highly expressed, stable receptor.

Endodomain

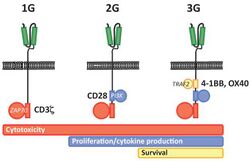

This is the functional end of the receptor. After antigen recognition, receptors cluster and a signal is transmitted to the cell.[16] The most commonly used endodomain component is CD3-zeta which contains 3 ITAMs. This transmits an activation signal to the T cell after the antigen is bound. CD3-zeta may not provide a fully competent activation signal and co-stimulatory signaling is needed. For example, chimeric CD28 and OX40 can be used with CD3-Zeta to transmit a proliferative/survival signal or all three can be used together.

History

First generation CARs were developed in 1989 by Gideon Gross and Zelig Eshhar[21][22] at Weizmann Institute, Israel.[23] The first generation of CARs are composed of an extracellular binding domain, a hinge region, a transmembrane domain, and one or more intracellular signaling domains.[4] Extracellular binding domain contains single‐chain variable fragments (scFvs) derived from tumor antigen‐reactive antibodies and usually have high specificity to tumor antigen.[4] All CARs harbor the CD3ζ chain domain as the intracellular signaling domain, which is the primary transmitter of signals. Second generation CARs also contain co‐stimulatory domains, like CD28 and/or 4‐1BB. The involvement of these intracellular signaling domains improve T cell proliferation, cytokine secretion, resistance to apoptosis, and in vivo persistence.[4] Besides co-stimulatory domains, the third‐generation CARs combine multiple signaling domains, such as CD3z-CD28-41BB or CD3z-CD28-OX40, to augment T cell activity. Preclinical data shows the third-generation CARs exhibit improved effector functions and in vivo persistence as compared to second‐generation CARs.[4] Recently, the fourth‐generation CARs (also known as TRUCKs or armored CARs), combine the expression of a second‐generation CAR with factors that enhance anti‐tumoral activity (e.g., cytokines, co‐stimulatory ligands).[24]

The evolution of CAR therapy is an excellent example of the application of basic research to the clinic. The PI3K binding site used was identified in co-receptor CD28,[25] while the ITAM motifs were identified as a target of the CD4- and CD8-p56lck complexes.[26]

The introduction of Strep-tag II sequence (an eight-residue minimal peptide sequence (Trp-Ser-His-Pro-Gln-Phe-Glu-Lys) that exhibits intrinsic affinity toward streptavidin[27]) into specific sites in synthetic CARs or natural T-cell receptors provides engineered T cells with an identification marker for rapid purification, a method for tailoring spacer length of chimeric receptors for optimal function and a functional element for selective antibody-coated, microbead-driven, large-scale expansion.[28][29] Strep-tag can be used to stimulate the engineered cells, causing them to grow rapidly. Using an antibody that binds the Strep-tag, the engineered cells can be expanded by 200-fold. Unlike existing methods this technology stimulates only cancer-specific T cells.[citation needed]

Smart T cell

Combined with exogenous molecules, some synthetic control devices have been implemented on CAR-T cells and alter the cell activity. Smart T cell is engineered with suicide gene or other synthetic control panels to precisely control therapeutic function over the timing and dosage, there by alleviating cytotoxicity.[30] Several strategies to improve safety and efficacy of CAR-T cells are:

Suicide gene engineering: engineered T cells are incorporated with suicide genes, which can be activated by extracellular molecule and then induce T cell apoptosis. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) and inducible caspase 9 (iCas9) are two types suicide genes have been integrated into CAR-T cells.[30][31][32] In iCas9 system, the suicide gene is composed of the sequence of the mutated FK506-binding protein with high specificity to a small-molecule, AP1903 and a gene encoding human caspase 9 switch. When the release of cytokines by CAR-T cells becomes more pronounced than basic levels, the iCas9 can be dimerized and lead to rapid apoptosis of T cells. Although both suicide genes demonstrate a noticeable function of as a safety switch in clinical trials for cellular therapies, some hinder defects limit the application of this strategy. HSV-TK is derived from virus and may be immunogenic to humans.[30][33] The suicide gene strategies may not act quickly enough to eliminate off-tumor cytotoxicity as well.

Dual-antigen receptor: T cells are engineered to express two tumor-associated antigen receptors at the same time. The dual-antigen receptor of engineered T cell module has been reported to have less intense side effects.[34] The activation of CAR-T cell via TCR-CD3ζ signal transduction pathway is transient and a complementary signal pathway provided by co-stimulatory molecules on antigen presenting cells promotes survival of modified-T cell can ability in controlling tumor.[35] An in vivo study in mice shows the dual-receptor T cells effectively eradicated prostate cancer and achieved complete long-term survival.[36]

ON-switch: ON-switch CAR-T cell split synthetic receptors into two parts: the first part mainly contains an antigen binding domain towards and the other part features two different downstream signaling elements (e.g. CD3ζ and 4-1BB). Upon the presence of an exogenous molecule (rapamycin analogs for example), two physically separated signaling elements fuse together and CAR-T cells exert therapeutic functions.[37] In this mechanism, the engineered T cell shows therapeutic function only in the presence of both tumor antigen and a benign exogenous molecule.

Bifunctional molecules as switches: The bispecific antibodies are developed as an efficacious bridge to target cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells and causes localized T cell activation. In this strategy, the bispecific antibody targets CD3 molecule of T cell and tumor-associated antigen presented on cancer cell surface.[38] The anti-CD20/CD3 bispecific molecule shows high specificity to both malignant B cells and cancer cells in mice.[39] FITC is another bifunctional molecule used in this strategy. FITC can redirect and regulate the activity of the FITC-specific CAR-T cells toward tumor cells with folate receptors.[40]

SMDC adaptor technology

SMDCs (small molecule drug conjugates) platform in immuno-oncology is a novel (currently experimental) approach that makes possible the engineering of a single universal CAR T cell, which binds with extraordinarily high affinity to a benign molecule designated as FITC. These cells are then used to treat various cancer types when co-administered with bispecific SMDC adaptor molecules. These unique bispecific adaptors are constructed with a FITC molecule and a tumor-homing molecule to precisely bridge the universal CAR T cell with the cancer cells, which causes localized T cell activation. Anti-tumor activity in mice is induced only when both the universal CAR T cells plus the correct antigen-specific adaptor molecules are present. Anti-tumor activity and toxicity can be controlled by adjusting the administered adaptor molecule dosing. Treatment of antigenically heterogeneous tumors can be achieved by administration of a mixture of the desired antigen-specific adaptors. Thus, several challenges of current CAR T cell therapies, such as:

- the inability to control the rate of cytokine release and tumor lysis

- the absence of an “off switch” that can terminate cytotoxic activity when tumor eradication is complete

- a requirement to generate a different CAR T cell for each unique tumor antigen

may be solved or mitigated using this approach.[41][42][43]

Clinical studies

As of August 2017, there were around 200 clinical trials happening globally involving CAR-T cells.[10] Around 65% of those trials targeted blood cancers, and 80% of them involved CD19 CAR-T cells targeting B-cell cancers.[10] In 2016, studies began to explore the viability of other antigens, such as CD20.[44]

FDA approvals

The first two FDA approved CAR-T therapies both target the CD19 antigen, which is found on many types of B-cell cancers.[45] Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) is approved to treat relapsed/refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), while axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) is approved to treat relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).[45]

Kymriah's clinical trial showed an 83% remission rate of all types of B-cell ALL after three months post treatment.[46] However, 49% of patients also suffered cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a serious side effect that has been responsible for several deaths in clinical trials run by Novartis’ competitors.[46]

See also

References

- ↑ Fox, Maggie (July 12, 2017). "New Gene Therapy for Cancer Offers Hope to Those With No Options Left". NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/new-gene-therapy-cancer-offers-hope-those-no-options-left-n741326.

- ↑ "Engineering CAR-T cells: Design concepts". Trends in Immunology 36 (8): 494–502. August 2015. doi:10.1016/j.it.2015.06.004. PMID 26169254.

- ↑ "The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design". Cancer Discovery 3 (4): 388–98. April 2013. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0548. PMID 23550147.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Clinical development of CAR T cells-challenges and opportunities in translating innovative treatment concepts.". EMBO Molecular Medicine 9 (9): 1183–1197. 2017. doi:10.15252/emmm.201607485.

- ↑ "Therapeutic potential of CAR-T cell-derived exosomes: a cell-free modality for targeted cancer therapy". Oncotarget 6 (42): 44179–90. December 2015. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.6175. PMID 26496034.

- ↑ "Time to put the CAR-T before the horse". Blood 118 (18): 4761–2. November 2011. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-09-376137. PMID 22053170.

- ↑ "Allogeneic lymphocyte-licensed DCs expand T cells with improved antitumor activity and resistance to oxidative stress and immunosuppressive factors". Molecular Therapy. Methods & Clinical Development 1: 14001. 2014-03-05. doi:10.1038/mtm.2014.1. PMID 26015949.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Clinical development of anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma". Cancer Science 108 (6): 1109–1118. June 2017. doi:10.1111/cas.13239. PMID 28301076.

- ↑ "Safe engineering of CAR T cells for adoptive cell therapy of cancer using long-term episomal gene transfer". EMBO Molecular Medicine 8 (7): 702–11. July 2016. doi:10.15252/emmm.201505869. PMID 27189167. http://embomolmed.embopress.org/content/8/7/702.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Clinical development of CAR T cells-challenges and opportunities in translating innovative treatment concepts". EMBO Molecular Medicine 9 (9): 1183–1197. September 2017. doi:10.15252/emmm.201607485. PMID 28765140.

- ↑ "Increased intensity lymphodepletion and adoptive immunotherapy--how far can we go?". Nature Clinical Practice Oncology 3 (12): 668–81. December 2006. doi:10.1038/ncponc0666. PMID 17139318.

- ↑ "Cytokine-release syndrome: overview and nursing implications". Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 11 (1 Suppl): 37–42. February 2007. doi:10.1188/07.CJON.S1.37-42. PMID 17471824.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Toxicity and management in CAR-T cell therapy". Molecular Therapy Oncolytics 3: 16011. 2016. doi:10.1038/mto.2016.11. PMID 27626062.

- ↑ "Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of JCAR015 in Adult B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL)". ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02535364.

- ↑ "CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 126 (6): 2123–38. June 2016. doi:10.1172/JCI85309. PMID 27111235.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Engineering CAR-T cells". Biomarker Research 5: 22. 2017-06-24. doi:10.1186/s40364-017-0102-y. PMID 28652918. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-017-0102-y.

- ↑ Monnier, Philippe P.; Vigouroux, Robin J.; Tassew, Nardos G. (April 2013). "In Vivo Applications of Single Chain Fv (Variable Domain) (scFv) Fragments". Antibodies 2 (2): 193–208. doi:10.3390/antib2020193. http://www.mdpi.com/2073-4468/2/2/193.

- ↑ "Chimeric fusion proteins used for therapy: indications, mechanisms, and safety". Drug Safety 38 (5): 455–79. May 2015. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0285-9. PMID 25832756.

- ↑ "The optimal antigen response of chimeric antigen receptors harboring the CD3zeta transmembrane domain is dependent upon incorporation of the receptor into the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex". Journal of Immunology 184 (12): 6938–49. June 2010. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901766. PMID 20483753.

- ↑ "Suicide gene therapy to increase the safety of chimeric antigen receptor-redirected T lymphocytes". Journal of Cancer 2: 378–82. 2011. doi:10.7150/jca.2.378. PMID 21750689.

- ↑ "Generation of effector T cells expressing chimeric T cell receptor with antibody type-specificity". Transplantation Proceedings 21 (1 Pt 1): 127–30. February 1989. PMID 2784887.

- ↑ "Tragedy, Perseverance, and Chance - The Story of CAR-T Therapy". The New England Journal of Medicine 377 (14): 1313–1315. October 2017. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1711886. PMID 28902570.

- ↑ "Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 86 (24): 10024–8. December 1989. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.24.10024. PMID 2513569. Bibcode: 1989PNAS...8610024G.

- ↑ "TRUCKs: the fourth generation of CARs.". Expert Opin Biol 15 (8): 1145–1154. 2015. doi:10.1517/14712598.2015.1046430.

- ↑ "Unifying concepts in CD28, ICOS and CTLA4 co-receptor signalling". Nature Reviews. Immunology 3 (7): 544–56. July 2003. doi:10.1038/nri1131. PMID 12876557.

- ↑ "Adaptors and molecular scaffolds in immune cell signaling". Cell 96 (1): 5–8. January 1999. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80953-8. PMID 9989491.

- ↑ "The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins". Nature Protocols 2 (6): 1528–35. 2007. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.209. PMID 17571060.

- ↑ "Inclusion of Strep-tag II in design of antigen receptors for T-cell immunotherapy". Nature Biotechnology 34 (4): 430–4. April 2016. doi:10.1038/nbt.3461. PMID 26900664.

- ↑ Crafting a better T cell for immunotherapy. New technology aims to reduce patients’ waiting time, increase potency of T-cell therapy

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "A new insight in chimeric antigen receptor‐engineered T cells for cancer immunotherapy.". Hematol Oncol 10 (1). 2017. doi:10.1186/s13045-016-0379-6.

- ↑ "HSV-TK gene transfer into donor lymphocytes for control of allogeneic graft-versus-leukemia.". Science 276: 1719–1724. 1997. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1719.

- ↑ "Co-expression of cytokine and suicide genes to enhance the activity and safety of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes.". Blood 110: 2793–2802. 2007. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-02-072843.

- ↑ "T-cell mediated rejection of gene-modified HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HIV-infected patients.". Nat Med 2: 216–223. 1996. doi:10.1038/nm0296-216.

- ↑ "Human T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity and proliferation directed by a single chimeric TCRζ/CD28 receptor.". Nat Biotechnol 20: 70–75. 2002. doi:10.1038/nbt0102-70.

- ↑ "Seventeen-gene signature from enriched Her2/Neu mammary tumor-initiating cells predicts clinical outcome for human HER2+: ERα−breast cancer.". PNAS 109: 5832–5837. 2012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201105109. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..109.5832L.

- ↑ "Dual targeting of ErbB2 and MUC1 in breast cancer using chimeric antigen receptors engineered to provide complementary signaling.". Clin Immunol 32: 1059–1070. 2012. doi:10.1007/s10875-012-9689-9.

- ↑ "Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor.". Science 350: aab4077. 2015. doi:10.1126/science.aab4077. Bibcode: 2015Sci...350.4077W.

- ↑ "Targeting T cells to tumor cells using bispecific antibodies.". Curr Opin Chem Biol 17: 385–392. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.03.029.

- ↑ "Anti-CD20/CD3 T cell-dependent bispecific antibody for the treatment of B cell malignancies.". Sci Transl Med 7: 287ra70. 2015. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4.

- ↑ "Bispecific small molecule-antibody conjugate targeting prostate cancer.". PNAS 110: 17796–17801. 2013. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316026110. Bibcode: 2013PNAS..11017796K.

- ↑ Lee, Yong Gu; Chu, Haiyan; Low, Philip S (2017). "Abstract LB-187: New methods for controlling CAR T cell-mediated cytokine storms". Cancer Research 77 (13 Supplement): LB-187. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-LB-187. Lay summary – Medical Xpress (April 21, 2016).

- ↑ SMDC TECHNOLOGY. ENDOCYTE

- ↑ "Endocyte Announces Promising Preclinical Data for Application of SMDC Technology in CAR T Cell Therapy in Late-Breaking Abstract at American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2016" (Press release). Endocyte. April 19, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ↑ "CAR T Cell Therapy: A Game Changer in Cancer Treatment". Journal of Immunology Research 2016: 5474602. 2016. doi:10.1155/2016/5474602. PMID 27298832. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jir/2016/5474602/.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Thumbs Up to Latest CAR-T cell Approval - New era for lymphoma, leukemia, possibly other cancers. Oct 2017

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "A Cure for Cancer? How CAR-T Therapy is Revolutionizing Oncology" (Press release). labiotech. March 8, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

External links