Biology:Progenitor cell

File:Neural progenitors in olfactory bulb.tif

A progenitor cell is a biological cell that can differentiate into a specific cell type. Stem cells and progenitor cells have this ability in common. However, stem cells are less specified than progenitor cells. Progenitor cells can only differentiate into their "target" cell type.[1] The most important difference between stem cells and progenitor cells is that stem cells can replicate indefinitely, whereas progenitor cells can divide only a limited number of times. Controversy about the exact definition remains and the concept is still evolving.[2]

The terms "progenitor cell" and "stem cell" are sometimes equated.[3]

Properties

Most progenitors are identified as oligopotent. In this point of view, they can compare to adult stem cells, but progenitors are said to be in a further stage of cell differentiation. They are "midway" between stem cells and fully differentiated cells. The kind of potency they have depends on the type of their "parent" stem cell and also on their niche. Some research found that progenitor cells were mobile and that these progenitor cells could move through the body and migrate towards the tissue where they are needed.[4] Many properties are shared by adult stem cells and progenitor cells.

Research

Progenitor cells have become a hub for research on a few different fronts. Current research on progenitor cells focuses on two different applications: regenerative medicine and cancer biology. Research on regenerative medicine has focused on progenitor cells, and stem cells, because their cellular senescence contributes largely to the process of aging.[5] Research on cancer biology focuses on the impact of progenitor cells on cancer responses, and the way that these cells tie into the immune response.[6]

The natural aging of cells, called their cellular senescence, is one of the main contributors to aging on an organismal level.[7] There are a few different ideas to the cause behind why aging happens on a cellular level. Telomere length has been shown to positively correlate to longevity.[8][9] Increased circulation of progenitor cells in the body has also positively correlated to increased longevity and regenerative processes.[10] Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are one of the main focuses of this field. They are valuable cells because they directly precede endothelial cells, but have characteristics of stem cells. These cells can produce differentiated cells to replenish the supply lost in the natural process of aging, which makes them a target for aging therapy research.[11] This field of regenerative medicine and aging research is still currently evolving.

Recent studies have shown that haematopoietic progenitor cells contribute to immune responses in the body. They have been shown to respond a range of inflammatory cytokines. They also contribute to fighting infections by providing a renewal of the depleted resources caused by the stress of an infection on the immune system. Inflammatory cytokines and other factors released during infections will activate haematopoietic progenitor cells to differentiate to replenish the lost resources.[12]

Examples

The characterization or the defining principle of progenitor cells, in order to separate them from others, is based on the different cell markers rather than their morphological appearance.[13]

- Satellite cells found in muscles. They play a major role in muscle cell differentiation and injury recoveries.

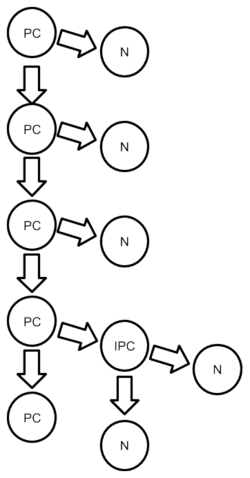

- Intermediate progenitor cells formed in the subventricular zone.[14] Some of these transit amplifying neural progenitors migrate via rostral migratory stream to the olfactory bulb and differentiate further into specific types of neural cells.

- Radial glial cells found in developing regions of the brain, most notably the cortex. These progenitor cells are easily identified by their long radial process.

- Bone marrow stromal cells found in the epidermis and make up 10% of progenitor cells. They are often classed as stem cells due to their high plasticity and potential for unlimited capacity for self-renewal.

- Periosteum contains progenitor cells that develop into osteoblasts and chondroblasts.

- Pancreatic progenitor cells are among the most studied progenitors.[15] They are used in research to develop a cure against diabetes type-1.

- Angioblasts or endothelial progenitor cells (EPC). These are very important for research on fracture and wounds healing.[16]

- Blast cells are involved in generation of B- and T-lymphocytes, which participate in immune responses.[17][15]

- Boundary cap cells from the neural crest form a barrier between the cells of the central nervous system and cells of the peripheral nervous system.[18] Boundary cap neural crest stem cells promote survival of mutant SOD1 motor neurons.[19]

Development of the human cerebral cortices

Before embryonic day 40 (E40), progenitor cells generate other progenitor cells; after that period, progenitor cells produce only dissimilar mesenchymal stem cell daughters. The cells from a single progenitor cell form a proliferative unit that creates one cortical column; these columns contain a variety of neurons with different shapes.[20]

See also

- Induced progenitor stem cells

- Endothelial progenitor cell

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

- ↑ Progenitor Cells : Biology, Characterization and Potential Clinical Applications. Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2013. pp. 26.

- ↑ "Stem and progenitor cells: the premature desertion of rigorous definitions". Trends in Neurosciences 26 (3): 125–31. March 2003. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00031-6. PMID 12591214.

- ↑ "progenitor cell" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Badami, Chirag D.; Livingston, David H.; Sifri, Ziad C.; Caputo, Francis J.; Bonilla, Larissa; Mohr, Alicia M.; Deitch, Edwin A. (September 2007). "Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells Mobilize to the Site of Injury After Trauma and Hemorrhagic Shock in Rats" (in en). Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care 63 (3): 596–602. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318142d231. ISSN 0022-5282. PMID 18073606. https://journals.lww.com/00005373-200709000-00016.

- ↑ "Effect of aging on stem cells". World Journal of Experimental Medicine 7 (1): 1–10. February 2017. doi:10.5493/wjem.v7.i1.1. PMID 28261550.

- ↑ "Concise Review: Modulating Cancer Immunity with Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells". Stem Cells 37 (2): 166–175. February 2019. doi:10.1002/stem.2933. PMID 30353618.

- ↑ Gilbert, Scott F.; Barresi, Michael J. F. (15 June 2016). Developmental biology (Eleventh ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer. ISBN 978-1-60535-470-5. OCLC 945169933.

- ↑ "Telomerase gene therapy: a novel approach to combat aging". EMBO Molecular Medicine 4 (8): 685–7. August 2012. doi:10.1002/emmm.201200246. PMID 22585424.

- ↑ "Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer". EMBO Molecular Medicine 4 (8): 691–704. August 2012. doi:10.1002/emmm.201200245. PMID 22585399.

- ↑ "Introduction to stem cell therapy". The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 24 (2): 98–103; quiz 104–5. March 2009. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e318197a6a5. PMID 19242274.

- ↑ Endothelial progenitor cells : a new real hope?. Cham: Springer. 2017. ISBN 978-3-319-55107-4. OCLC 988870936.

- ↑ "Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response". Nature Reviews. Immunology 11 (10): 685–92. September 2011. doi:10.1038/nri3062. PMID 21904387.

- ↑ "Muscle satellite cells". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 35 (8): 1151–6. August 2003. doi:10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00042-6. PMID 12757751.

- ↑ "Contribution of intermediate progenitor cells to cortical histogenesis". Archives of Neurology 64 (5): 639–42. May 2007. doi:10.1001/archneur.64.5.639. PMID 17502462.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Thymus-bound: the many features of T cell progenitors". Frontiers in Bioscience 3 (3): 961–9. June 2011. doi:10.2741/200. PMID 21622245.

- ↑ "The ever-elusive endothelial progenitor cell: identities, functions and clinical implications". Pediatric Research 59 (4 Pt 2): 26R–32R. April 2006. doi:10.1203/01.pdr.0000203553.46471.18. PMID 16549545.

- ↑ "Losing B cell identity". BioEssays 30 (3): 203–7. March 2008. doi:10.1002/bies.20725. PMID 18293359.

- ↑ "New insights on Schwann cell development". Glia 63 (8): 1376–93. 2015. doi:10.1002/glia.22852. PMID 25921593.

- ↑ Aggarwal, T; Hoeber, J; Ivert, P; Vasylovska, S; Kozlova, EN (July 2017). "Boundary Cap Neural Crest Stem Cells Promote Survival of Mutant SOD1 Motor Neurons.". Neurotherapeutics 14 (3): 773–783. doi:10.1007/s13311-016-0505-8. PMID 28070746.

- ↑ "Building brains in a dish: Prospects for growing cerebral organoids from stem cells". Neuroscience 334: 105–118. October 2016. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.07.048. PMID 27506142.

|