Biography:Kenneth Nichols

Kenneth Nichols CBE | |

|---|---|

Nichols at his desk in 1945 | |

| Born | 13 November 1907 Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | 21 February 2000 (aged 92) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Place of burial | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1929–1953 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands held | Armed Forces Special Weapons Project Manhattan Engineer District |

| Battles/wars | Occupation of Nicaragua World War II |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal (2) United States Atomic Energy Commission Distinguished Service Award Commander of the Order of the British Empire (Great Britain) Medal of Merit (Nicaragua) |

| Alma mater | Cornell University (BS, MS) University of Iowa (PhD) |

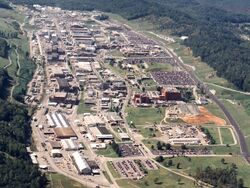

Kenneth David Nichols CBE (13 November 1907 – 21 February 2000) was an officer in the United States Army, and a civil engineer who worked on the secret Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb during World War II. He served as Deputy District Engineer to James C. Marshall, and from 13 August 1943 as the District Engineer of the Manhattan Engineer District. Nichols led both the uranium production facility at the Clinton Engineer Works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the plutonium production facility at Hanford Engineer Works in Washington state.

Nichols remained with the Manhattan Project after the war until it was taken over by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1947. He was the military liaison officer with the Atomic Energy Commission from 1946 to 1947. After briefly teaching at the United States Military Academy at West Point, he was promoted to major general and became chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, responsible for the military aspects of atomic weapons, including logistics, handling and training. He was deputy director for the Atomic Energy Matters, Plans and Operations Division of the Army's general staff, and was the senior Army member of the military liaison committee that worked with the Atomic Energy Commission.

In 1950, General Nichols became deputy director of the Guided Missiles Division of the Department of Defense. He was appointed chief of research and development when it was reorganized in 1952. In 1953, he became the general manager of the Atomic Energy Commission, where he promoted the construction of nuclear power plants. He played a key role in the security clearance hearing against J. Robert Oppenheimer that resulted in Oppenheimer's security clearance being revoked. In later life, Nichols became an engineering consultant on private nuclear power plants.

Early life

Kenneth David Nichols was born on 13 November 1907 in West Park, Ohio, which later became part of Cleveland, Ohio, one of four children of Wilbur L. Nichols and his wife Minnie May Colbrunn.[1] He graduated fifth in his class at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1929 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Army Corps of Engineers. In 1929, Nichols went to Nicaragua as part of an expedition led by Lieutenant Colonel Daniel I. Sultan whose purpose was to conduct a survey for the Inter-Oceanic Nicaragua Canal.[2] A fellow officer in the expedition, who would later figure prominently in Nichols's career, was First Lieutenant Leslie Groves.[3] For his service on the expedition, Nichols was awarded the Nicaraguan Medal of Merit "for exceptional service rendered [to] the Republic of Nicaragua."[2]

Nichols returned to the United States in 1931 and went to Cornell University, where he received a bachelor's degree in civil engineering. He became assistant to the Director of the Waterways Experiment Station in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in June 1932. In August he continued his studies at Cornell, where he completed his master's degree in civil engineering on 10 June 1933.[2] While at Cornell he married Jacqueline (Jackie) Darrieulat.[3] Their marriage produced a daughter (Jan) and a son (David).[1][4]

He returned to the Waterways Experiment Station in 1933. The next year he received a fellowship awarded by the Institute of International Education to study European Hydraulic Research Methods for a year at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin. While there he was promoted to first lieutenant on 1 October 1934. The thesis he wrote won an American Society of Civil Engineers award.[3] On returning to the United States he received another one-year posting to the Waterways Experiment Station. From September 1936 to June 1937 he was a student officer at Fort Belvoir, Virginia.[2] He then became a student again, using his Technische Hochschule thesis as the basis for a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the State University of Iowa.[3] He became an instructor at West Point in August 1937, where he was promoted to captain on 13 June 1939.[2]

World War II

In June 1941, Colonel James C. Marshall summoned Nichols to the Syracuse Engineer District to become area engineer in charge of construction of the Rome Air Depot.[5] He was promoted to major on 10 October 1941 and lieutenant colonel on 1 February 1942,[6] when Marshall asked him to take on additional responsibility as area engineer in charge of construction of a new TNT plant, the Pennsylvania Ordnance Works, in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. On this project, Nichols worked with DuPont and Stone & Webster as major contractors, and dealt with Leslie Groves, now the colonel in charge of military construction.[5]

In June 1942, Nichols was again summoned by Marshall, this time to Washington, D.C.[7] Marshall had recently been appointed as district engineer of the new Manhattan Engineer District (MED), and had received authorization to staff it by drawing on officers and civilians working for the Syracuse Engineer District, which was now winding down as the major part of its construction program was nearing completion. Marshall started by designating Nichols as his Deputy District Engineer, which became effective when the Manhattan District was officially formed on 16 August 1942.[8]

The first major decision confronting the new district, which unlike other engineer districts had no geographic limits, was the choice of construction site. On 30 June Nichols and Marshall set out for Tennessee, where they met with officials of the Tennessee Valley Authority and looked over prospective sites in the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains that had been identified (by scouts from the Office of Scientific Research and Development) as possessing the desirable attributes of abundant electric power, water and transportation with sparse population. A site at Oak Ridge, Tennessee was chosen, but Marshall delayed purchase while he awaited scientific results that justified a full-scale plant. Afterwards, Nichols visited the Metallurgical Laboratory, or "Met Lab", at the University of Chicago, where he met with Arthur Compton. Seeing the problems of overcrowding there, Nichols, on his own authority, arranged for a new experimental site to be established in the Argonne Forest which would eventually become the Argonne National Laboratory.[9]

Nichols took charge of ore procurement. He arranged with the State Department for export controls to be placed on uranium oxide and negotiated with Edgar Sengier for the purchase of 1,200 tons of ore from the Belgian Congo that was being stored in a warehouse on Staten Island. Nichols arranged with the Eldorado Mining and Refining Company for the purchase of ore from its mine in Port Hope, Ontario, and its shipment in 100-ton lots.[10] Nichols met with Undersecretary of the Treasury Daniel W. Bell and arranged for the transfer of 14,700 tons of silver from the West Point Depository for use in the Y-12 National Security Complex in place of copper, which was in desperately short supply in wartime.[11] When Nichols initially said he needed six thousand tons of silver, neither of them could initially convert the weight to troy ounces. When Nichols said, "What difference does it make how we express the quantity?", Bell replied, "Young man, you may think of silver in tons, but the Treasury will always think of silver in troy ounces."[12]

In September 1942, Groves, now a brigadier general, became director of the Manhattan Project.[13] Groves immediately moved on the most urgent issues. He promptly approved the purchase of the site at Oak Ridge and negotiated for the project to be given a AAA priority rating.[14] Groves soon decided to establish his project headquarters on the fifth floor of the New War Department Building in Washington, D.C., where Marshall had maintained a liaison office.[15]

Nichols, who concentrated his attention on ore procurement, feed materials and the plutonium project,[16] was promoted to colonel on 22 May 1943.[6] On 13 August, he replaced Marshall as District Engineer of the Manhattan Engineer District.[17] As District Engineer, Nichols was responsible for both the uranium production facility at the Clinton Engineer Works at Oak Ridge and the plutonium production facility at the Hanford Site. One of his first tasks as district engineer was to move the district headquarters to Oak Ridge, although its name did not change.[18] For his wartime work on the Manhattan Project, Nichols was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by the United States Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson.[19]

Post war

Nichols was promoted to brigadier general on 22 January 1946.[6] Following the departure of Major General Thomas Farrell, Nichols became Groves's deputy, although he also continued as district engineer. Asked to spend more time on weapons production and storage, Nichols established a new underground assembly plant at the Mound Laboratories in Miamisburg, Ohio, and recommended that Sandia Base be transferred from the United States Army Air Corps to the Manhattan District.[19]

In June 1946, Nichols went to Bikini Atoll to represent the Manhattan Project at Operation Crossroads, a series of nuclear weapons tests conducted to investigate their effects on warships.[20] Like many of his contemporaries in an Army that was dramatically reduced in size as it rapidly demobilized, Nichols was reduced in rank, reverting to his substantive rank of lieutenant colonel on 30 June 1946.[6] On return from Bikini, he found that he had been made an honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire.[21]

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 created the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to take over the functions and assets of the Manhattan Project. President Harry S. Truman appointed its five commissioners on 28 October 1946, and Groves appointed Nichols as the military liaison officer to the AEC. Nichols's main responsibility was to help organize an orderly transfer of assets and responsibilities from the MED to the AEC.[22] Military aspects were taken over by the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP).[23] It was generally assumed that Nichols would become the AEC's Director of Military Application, but while Nichols's relationship with the AEC was cordial and the commissioners were impressed with his administrative skills, it also became clear that Nichols did not agree with the commissioners' concept of the Director of Military Application as a staff rather than a line function.[24]

In December 1946, Nichols recommended the closing down of the alpha tracks of the Y-12 plant, thereby cutting the Tennessee Eastman payroll from 8,600 to 1,500 and saving $2 million a month. Henceforth, uranium enrichment would be performed by the gaseous diffusion plants, the wartime K-25 and the new K-27,[25] which had commenced operation in January 1946.[26] AEC Chairman David E. Lilienthal objected, but Nichols pointed out that the proposal had been included in their briefing when the commission visited Oak Ridge in November.[27] Nichols kept the national laboratories operating with $60 million worth of research grants for fiscal year 1947.[28] He helped Captain Hyman G. Rickover train a team of naval engineers at Oak Ridge in nuclear propulsion.[29]

In February 1947 Nichols was appointed Professor of Mechanics at West Point, a move mooted in November 1946. He had been rejected for a new position at the AEC by Lilienthal; though he agreed to be available for consultation on atomic matters as Groves was planning to retire (although he then accepted a new military position). Nichols wished the military, rather than the AEC, to have custody of (atomic) weapons. Lilienthal's opponents in Congress objected to the departure of the two men best informed about atomic matters. With a retirement age of 65 he looked forward to almost 26 years of "pleasant and comfortable" academic life with a house on the Hudson, and to Jackie "a wonderful place to raise Jan and David". He was to leave as deputy manager of the AEC in January 1947.[27]

But in January 1948 he returned to the army to replace Groves as chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP), as the Navy and Air Force were vetoing each other's candidate. On 11 March he and Lilienthal were summoned to the White House where Truman told them, "I know you two hate each other’s guts." Truman directed that "the primary objective of the AEC was to develop and produce atomic weapons". Lilienthal was told he would have to "forgo your desire to place a bottle of milk on every doorstop and get down to the business of producing atomic weapons". Nichols had been looking forward to "a long relaxing career as a professor during a long period of peace" but saw increased tension with the Soviet Union in February and March.[30]

In April 1948, Nichols was appointed to command the AFSWP, with the rank of major general,[6] becoming the youngest major general in the Army at the time. Although his rank entitled him to quarters at Fort Myer, Virginia, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General Omar Bradley advised him not to ask for them as there had been criticism from some senior colonels.[31] Nichols also became Senior Army Member of the Military Liaison Committee to the AEC, and Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff of the Army (G-3) for Atomic Energy.[6]

In his new role Nichols clashed with the AEC over the issue of whether it or the Department of Defense should have custody of nuclear weapons. The administration's policy remained firmly in favor of AEC control. This was tested during the Berlin Blockade, when Truman ordered B-29 bombers to Europe.[32] For a time there was talk of calling off the Operation Sandstone nuclear weapons tests, but Nichols successfully argued for their continuation.[33] In 1950, he became deputy director of the Guided Missiles Division of the Department of Defense, overseeing the Nike Project.[34] He was appointed Chief of Research and Development when it was reorganized in 1952.[35] Nichols retired from the Army on 31 October 1953. For his services from 1948 to 1953, he was belatedly awarded a second Distinguished Service Medal in 1956.[36]

Nichols became General Manager of the AEC on 2 November 1953.[36] In this capacity he initiated the AEC Personnel Security Board hearing on the loyalty and trustworthiness of atomic scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer. In a harshly worded memorandum to the AEC on 12 June 1954, subsequent to the hearing, Nichols recommended that Oppenheimer's security clearance not be reinstated. In five "security findings", Nichols said that Oppenheimer was "a Communist in every sense except that he did not carry a party card," and that he "is not reliable or trustworthy."[37] The commission agreed, and Oppenheimer was stripped of his security clearance.[38] A second scandal was the Dixon-Yates contract, a political controversy that became a major issue in the 1954 elections, resulting in Nichols appearing before a United States Senate subcommittee.[39]

Later life

Nichols left the Atomic Energy Commission in 1955 and opened a consulting firm on K Street, specializing in commercial atomic energy research and development. His clients included Alcoa, Gulf Oil, Westinghouse Electric Corporation and the Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station.[40] Nichols was involved with the construction of the Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station, the first privately owned pressurized-water plant, and the Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant, which commenced operation in 1961 and 1968 respectively. They were both experimental and not expected to be competitive with coal and oil, but later became more so due to inflation and large increases in coal and oil prices. He was critical of over-regulation and protracted hearings, which meant that by the 1980s similar boiling-water or pressurized-water plants took almost twice as long to build in the United States as in France, Japan, Taiwan or South Korea.[41]

Nichols died of respiratory failure on 21 February 2000 at the Brighton Gardens retirement home in Bethesda, Maryland. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[40]

Portrayals

Nichols is played by Christopher Muncke in the BBC presentation Oppenheimer (1980)[42] and by Dane DeHaan in Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer (2023).[43]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [1] Familysearch.org

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cullum 1940, p. 778

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Nichols 1987, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 249, 257.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nichols 1987, pp. 28–29

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Cullum 1950, p. 593

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 31

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 42–44

- ↑ Fine & Remington 1972, pp. 655–658

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 85–86

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 153

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 42

- ↑ Fine & Remington 1972, pp. 659–661

- ↑ Jones 1985, pp. 78–82

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 67

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 99–101

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 88

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Nichols 1987, pp. 226–229

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 232–233

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 243–244

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 394–398.

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 648–651

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 646

- ↑ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 630

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Nichols 1987, pp. 244–247.

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 28

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 74–76

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 257–259.

- ↑ Nichols 1987, p. 258

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, pp. 169–172, 354–355

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 159

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 280–284

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 288–291

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Nichols 1987, pp. 298–299

- ↑ Stern & Green 1969, pp. 394–398, 400–401

- ↑ Hewlett & Holl 1989, pp. 64–65, 102–108

- ↑ Hewlett & Holl 1989, pp. 127–133

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Kenneth David Nichols, Arlington National Cemetery, http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/kdnichols.htm, retrieved 16 October 2010

- ↑ Nichols 1987, pp. 343–345

- ↑ "Christopher Muncke". BFI. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2ba32e3137.

- ↑ Moss, Molly; Knight, Lewis (July 22, 2023). "Oppenheimer cast: Full list of actors in Christopher Nolan film". Radio Times. https://www.radiotimes.com/movies/oppenheimer-cast-christopher-nolan-murphy/. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

References

- Cullum, George W. (1940). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VIII 1930–1940. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16919coll3/id/19424/rec/9. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1950). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume IX 1940–1950. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16919coll3/id/22314/rec/10. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Fine, Lenore; Remington, Jesse A. (1972). The Corps of Engineers: Construction in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 834187. http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/010/10-5/index.html. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Groves, Leslie (1962). Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Harper. OCLC 537684. https://archive.org/details/nowitcanbetolds00grov.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, Volume I, 1939–1946. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. OCLC 26583399. https://www.governmentattic.org/5docs/TheNewWorld1939-1946.pdf.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, Volume II, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Holl, Jack M. (1989). Atoms for Peace and War, Volume III, 1953–1961 Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-06018-0. OCLC 82275622.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875. http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/011/11-10/index.html. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Nichols, Kenneth D. (1987). The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-06910-X. OCLC 15223648.

- Stern, Philip; Green, Harold P. (1969). The Oppenheimer Case: Security on Trial. New York, New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-014101-8. OCLC 31389. https://archive.org/details/oppenheimercases00sterrich.

External links

|