Biology:Common merganser

| Common merganser | |

|---|---|

| |

| M. m. merganser, male in Sandwell, England | |

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination | |

| M. m. americanus, female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Animalia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Chordata |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Aves |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Anseriformes |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Anatidae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Mergus |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | <div style="display:inline" class="script error: no such module "taxobox ranks".">M. merganser |

| Binomial name | |

| Mergus merganser | |

| Subspecies | |

|

3, see text | |

| |

| M. merganser range Breeding Resident Passage Non-breeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Merganser americanus Cassin, 1852 | |

The common merganser (North American) or goosander (Eurasian) (Mergus merganser) is a large sea duck of rivers and lakes in forested areas of Europe, Asia, and North America. The common merganser eats mainly fish. It nests in holes in trees.

Taxonomy

The first formal description of the common merganser was by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae. He introduced the current binomial name Mergus merganser.[2] The genus name is a Latin word used by Pliny and other Roman authors to refer to an unspecified waterbird, and merganser is derived from mergus and anser, Latin for "goose".[3] In 1843 John James Audubon used the name "Buff-breasted Merganser" in addition to "goosander" in his book The Birds of America.[4]

The three subspecies differ in only minor detail:[5][6]

- M. m. merganser – Linnaeus, 1758 is found throughout northern Europe and northern Asiatic Russia.

- M. m. orientalis – Gould, 1845 (syn. M. m. comatus – Salvadori, 1895) is found in the Central Asian mountains. Slightly larger than M. m. merganser, it has a more slender bill.

- M. m. americanus – Cassin, 1852 is found in North America. Its bill is broader-based than in M. m. merganser, and a black bar crosses the white inner wing (visible in flight) on males.

Description

It is 58–72 cm (23–28 1⁄2 in) long with a 78–97 cm (30 1⁄2–38 in) wingspan and a weight of 0.9–2.1 kg (2 lb 0 oz–4 lb 10 oz); males average slightly larger than females, but with some overlap. Like other species in the genus Mergus, it has a crest of longer head feathers, but these usually lie smoothly rounded behind the head, not normally forming an erect crest. Adult males in breeding plumage are easily distinguished, the body white with a variable salmon-pink tinge, the head black with an iridescent green gloss, the rump and tail grey, and the wings largely white on the inner half, black on the outer half. Females and males in "eclipse" (non-breeding plumage, July to October) are largely grey, with a reddish-brown head, white chin, and white secondary feathers on the wing. Juveniles (both sexes) are similar to adult females but also show a short black-edged white stripe between the eye and bill. The bill and legs are red to brownish-red, brightest on adult males, dullest on juveniles.[5][6][7]

Behaviour

Feeding

Like the other mergansers, these piscivorous ducks have serrated edges to their bills to help them grip their prey, so they are often known as "sawbills". In addition to fish, they take a wide range of other aquatic prey, such as molluscs, crustaceans, worms, insect larvae, and amphibians; more rarely, small mammals and birds may be taken.[5][6] As in other birds with the character, the salmon-pink tinge shown variably by males is probably diet-related, obtained from the carotenoid pigments present in some crustaceans and fish.[8] When not diving for food, they are usually seen swimming on the water surface, or resting on rocks in midstream or hidden among riverbank vegetation, or (in winter) on the edge of floating ice.[5][6]

Habits

In most places, the common merganser is as much a frequenter of salt water as fresh water. In larger streams and rivers, they float down with the stream for a few miles, and either fly back again or more commonly fish their way back, diving incessantly the whole way. In smaller streams, they are present in pairs or smaller groups, and they float down, twisting round and round in the rapids, or fishing vigorously in a deep pool near the foot of a waterfall or rapid. When floating leisurely, they position themselves in water similar to ducks, but they also swim deep in water like cormorants, especially when swimming upstream. They often sit on a rock in the middle of the water, similar to cormorants, often half-opening their wings to the sun. To rise from water, they flap along the surface for many yards. Once they are airborne, their flight is strong and rapid.[9] They often fish in a group forming a semicircle and driving the fish into shallow water, where they are captured easily. Their ordinary voice is a low, harsh croak, but during the breeding season, males in display, as well as young, make a plaintive, soft whistle. Generally, they are wary, and one or more birds stay on sentry duty to warn the flock of approaching danger. When disturbed, they often disgorge food before moving.[10] Though they move clumsily on land, they resort to running when pressed, assuming a very upright position similar to penguins, and falling and stumbling frequently.[11]

Breeding

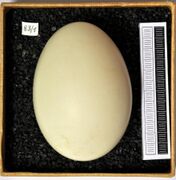

Nesting is normally in a tree cavity, so it requires mature forest as its breeding habitat; they also readily use large nest boxes where provided, requiring an entrance hole 15 cm (6 in) in diameter.[12] In places devoid of trees (like Central Asian mountains), they use holes in cliffs and steep, high banks, sometimes at considerable distances from the water.[10] The female lays 6–17 (most often 8–12) white to yellowish eggs, and raises one brood in a season. The ducklings are taken by their mother in her bill to rivers or lakes immediately after hatching, where they feed on freshwater invertebrates and small fish fry, fledging when 60–70 days old. The young are sexually mature at the age of two years.[5][6][7] Common mergansers are known to form crèches, with single females having been observed with over 70 ducklings at one time.[13]

Movements

The species is a partial migrant, with birds moving away from areas where rivers and major lakes freeze in the winter, but resident where waters remain open. Eastern North American birds move south in small groups to the United States wherever ice-free conditions exist on lakes and rivers; on the milder Pacific coast, they are permanent residents. Scandinavian and Russia n birds also migrate southwards, but western European birds, and a few in Japan , are largely resident.[5][6] In some populations, the males also show distinct moult migration, leaving the breeding areas as soon as the young hatch to spend the summer (June to September) elsewhere. Notably, most of the western European male population migrates north to estuaries in Finnmark in northern Norway (principally Tanafjord) to moult, leaving the females to care for the ducklings. Much smaller numbers of males also use estuaries in eastern Scotland as a moulting area.[7][14][15]

Status and conservation

Overall, the species is not threatened, though illegal persecution by game-fishing interests is a problem in some areas.[16] In February 2020, a rare common merganser sighting was documented in Central Park, New York; the bird was in obvious distress, with its beak being trapped by a piece of debris.[17]

Within western Europe, a marked southward spread has occurred from Scandinavia in the breeding range since about 1850, colonising Scotland in 1871, England in 1941, and also a strong increase in the population in the Alps.[7] They are very scarce in Ireland, with regular breeding confined to a few pairs in County Wicklow.[18]

The goosander is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds applies.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2018). "Mergus merganser". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22680492A132054083. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22680492A132054083.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22680492/132054083. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1758) (in la). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, Volume 1. v.1 (10th ed.). Holmiae:Laurentii Salvii. p. 129. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/727034.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 250–251. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. https://archive.org/details/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling.

- ↑ Audubon, J.J. (1843). The birds of America. 6. pp. 387–394. https://books.google.com/books?id=X4RIAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA387.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J., eds (1992). Handbook of the Birds of the World. 1. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 626. ISBN 978-84-87334-10-8. https://archive.org/details/handbookofbirdso0001unse/page/626.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Madge, S.; Burn, H. (1987). Wildfowl: An Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese and Swans of the World. A & C Black. ISBN 978-0-7470-2201-5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Snow, D.W.; Perrins, C.M. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic (Concise ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- ↑ Hudon, J.; Brush, A.H. (1990). "Carotenoids produce flush in the Elegant Tern plumage". The Condor 92 (3): 798–801. doi:10.2307/1368708. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/condor/v092n03/p0798-p0801.pdf.

- ↑ Hume, A.O.; Marshall, C.H.T. (1880). The Game birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. 3. Self published. https://archive.org/stream/GameBirdsOfIndia3/HumeGameBirds3#page/n331/mode/2up.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Baker, E.C.S. (1928). Fauna of British India. Birds. 5 (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 470–473. https://archive.org/stream/BakerFbiBirds6/BakerFBI6#page/n511/mode/1up.

- ↑ Baker, E.C. Stuart (1922). The game birds of India, Burma and Ceylon. 1. London, Bombay Natural History Society. pp. 317–327. https://archive.org/stream/gamebirdsofindia01bake#page/n405/mode/2up.

- ↑ du Feu, C. (2005). Nestboxes. British Trust for Ornithology Field Guide. Thetford: The British Trust for Ornithology. http://www.bto.org/sites/default/files/u15/downloads/publications/guides/nestbox.pdf.

- ↑ Mervosh, Sarah (2018-07-24). "1 Hen, 76 Ducklings: What's the Deal With This Picture?". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/24/science/merganser-ducklings-photo.html.

- ↑ Little, B.; Furness, R.W. (1985). "Long distance moult migration by British Goosanders Mergus merganser". Ringing & Migration 6 (2): 77–82. doi:10.1080/03078698.1985.9673860.

- ↑ Hatton, P.L.; Marquiss, M. (2004). "The origins of moulting Goosanders on the Eden Estuary". Ringing & Migration 22 (2): 70–74. doi:10.1080/03078698.2004.9674315.

- ↑ "Crimes against birds". Partnership for Action Against Wildlife Crime in Scotland. 2009-12-07. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Environment/Wildlife-Habitats/paw-scotland/types-of-crime/crimes-against-birds.

- ↑ Kilgannon, Corey (2020-02-24). "Central Park Races to Save a Rare Duck Gagging on a Piece of Plastic" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/24/nyregion/central-parks-duck-plastic.html.

- ↑ Report of the Irish Rare Breeding Birds Panel 2013 Irish Birds Vol. 10 p.65

External links

- "Goosander media". Internet Bird Collection. http://www.hbw.com/ibc/species/goosander-mergus-merganser.

- Common Merganser photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

Wikidata ☰ Q180991 entry

|