Biology:Dacentrurus

| Dacentrurus | |

|---|---|

| |

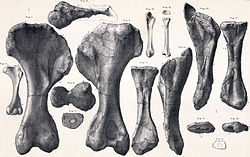

| Holotype specimen, London | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Animalia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Chordata |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Dinosauria |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Ornithischia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Thyreophora |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Stegosauria |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Stegosauridae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Dacentrurinae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | †Dacentrurus Lucas, 1902 |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | <div style="display:inline" class="script error: no such module "taxobox ranks".">†D. armatus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Dacentrurus armatus (Owen, 1875 [originally Omosaurus])

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Dacentrurus (meaning "tail full of points"), originally known as Omosaurus, is a genus of stegosaurian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous (154 - 140 mya) of Europe. Its type species, Omosaurus armatus, was named in 1875, based on a skeleton found in a clay pit in the Kimmeridge Clay in Swindon, England . In 1902 the genus was renamed Dacentrurus because the name Omosaurus had already been used for a crocodylian. After 1875, half a dozen other species would be named but perhaps only Dacentrurus armatus is valid. Finds of this animal have been limited and much of its appearance is uncertain. It was a heavily built quadrupedal herbivore, adorned with plates and spikes, reaching 8–9 metres (26–30 ft) in length and 5 metric tons (5.5 short tons) in body mass.

Discovery and species

On 23 May 1874, James Shopland of the Swindon Brick and Tyle Company reported to Professor Richard Owen that their clay pit, the Swindon Great Quarry below Old Swindon Hill at Swindon in Wiltshire, had again produced a fossil skeleton. Owen sent out William Davies to secure the specimen, which proved to be encased in an eight feet high clay nodule. During an attempt to lift it in its entirety, the loam clump crumbled into several pieces. These were eventually transported to London in crates with a total weight of three tonnes. The bones were subsequently partially uncovered by Owen's preparator, the mason Caleb Barlow.[1]

Owen named and described the remains in 1875 as the type species Omosaurus armatus. The generic name is derived from Greek ὦμος, omos, "upper arm", in reference to the robust humerus. The specific name armatus can mean "armed" in Latin and in this case refers to a large spike that Owen assumed was present on the upper arm.[2]

The holotype, NHMUK 46013, was found in a layer of the Kimmeridge Clay Formation dating from the late Kimmeridgian. The main nodule fragment contains the pelvis; a series of six posterior dorsal vertebrae, all sacrals and eight anterior caudal vertebrae; a right femur and some loose vertebrae. In all, thirteen detached vertebrae are present in the material. Also an almost complete left forelimb was contained by another loam clump. Additional elements include a partial fibula with calcaneum, a partial tibia, a right neck plate and a left tail spike.

Several other species would be named within the genus Omosaurus. Part of the British Museum of Natural History collection was specimen NHMUK 46321, a pair of spike bases found in the Kimmeridge Clay by William Cunnington near the Great Western Railway cutting near Wootton Bassett. These Owen in 1877 named Omosaurus hastiger, the epithet meaning "spike-bearer" or "lance-wielder", the spikes by him seen as placed on the wrist of the animal.[3] In 1887, John Whitaker Hulke named Omosaurus durobrivensis based on specimen NHMUK R1989 found at Tanholt, close to Eye, Cambridgeshire, the specific name being derived from Durobrivae.[4] (That specimen is sometimes mistakenly said to have been found at Fletton, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, which is where Alfred Nicholson Leeds made most of his finds.) This in 1956 became the separate genus Lexovisaurus. In 1893, Harry Govier Seeley named Omosaurus phillipsii, based on a femur, specimen YM 498, the epithet honouring the late John Phillips.[5] Seeley suggested this may be the same taxon as Priodontognathus phillipsii Seeley 1869, which has led to the misunderstanding, due to its having the same specific name, that Priodontognathus was simply subsumed by him under Omosaurus. This interpretation however, is incorrect as both species have different holotypes. "Omosaurus leedsi" is a nomen nudum used by Seeley on a label for CAMSM J.46874, a plate found in Cambridgeshire, the epithet honouring Alfred Nicholson Leeds.[6] In 1910 Friedrich von Huene named Omosaurus vetustus, based on specimen OUM J.14000, a femur found in the west bank of Cherwell River, the epithet meaning "the ancient one".[7] In 1911 Franz Nopcsa named Omosaurus lennieri, the epithet honouring Gustave Lennier, based on a partial skeleton in 1899 found in the Kimmeridgian Argiles d'Octeville near Cap de la Hève in Normandy, France .[8] The specimen would be destroyed during the allied bombing of Caen in 1944.

Even as the last two Omosaurus species were named, it had become known that the name Omosaurus had been preoccupied by a "crocodilian" (in fact a phytosaur), Omosaurus perplexus Leidy 1856.[9] In 1902 Frederick Augustus Lucas renamed the genus into Dacentrurus. The name is derived from Greek δα~, da~, "very" or "full of", κέντρον, kentron, "point", and οὐρά, oura, "tail".[10] Lucas only gave a new combination name for the type species Omosaurus armatus: Dacentrurus armatus, but in 1915 Edwin Hennig moved most Omosaurus species to Dacentrurus, resulting in a Dacentrurus hastiger, Dacentrurus durobrivensis, Dacentrurus phillipsi and a Dacentrurus lennieri.[11] Nevertheless, it would be common for researchers to use the name Omosaurus instead until the middle of the twentieth century.[12] D. vetustus, earlier indicated as Omosaurus (Dacentrurus) vetustus by von Huene, was included with Lexovisaurus as a Lexovisaurus vetustus in 1983,[13] but that assignment was rejected with both editions of the Dinosauria,[14][15] and O. vetustus is now the type species of "Eoplophysis".[16]

In 2021, remains attributed to Dacentrurus sensu lato were reported from the earliest Cretaceous (Berriasian) Angeac-Charente bonebed of France, these consisted of a partial skeleton including parts of the braincase, vertebrae, ribs and phalanges.[17]

Distribution

Due to the fact it represented the best known stegosaurian species from Europe, most stegosaur discoveries in this area were referred to Dacentrurus.[18] This included finds in Wiltshire and Dorset in southern England (among them a vertebra ascribed to D. armatus in Weymouth[19]), fossils from France and Spain and five more historically recent skeletons from Portugal. Most of these finds were fragmentary in nature; the only more complete skeletons were the holotypes of D. armatus and D. lennieri. Eventually the strata from which Dacentrurus was reported amounted to the following list:

- Argiles d'Octeville[20]

- Camadas de Alcobaça[20]

- Kimmeridge Clay[20]

- Lourinhã Formation

- Unidade Bombarral[20]

- Villar del Arzobispo Formation[18]

Eggs attributed to Dacentrurus have been discovered in Portugal.

Peter Malcolm Galton in the eighties referred all stegosaur remains from Late Jurassic deposits in western Europe to D. armatus.[19] A radically different approach was in 2008 taken by Susannah Maidment who limited the material of D. armatus to its holotype. Most named species, among them Astrodon pusillus from Portugal based on stegosaur fossils,[21] she considered nomina dubia. She considered the specimens from mainland Europe possibly a separate species, but as it was too limited to establish distinctive traits she assigned it to Dacentrurus sp.[22]

In 2013, Alberto Cobos and Francisco Gascó described stegosaurian vertebral remains, which were found grouped together in the "Barranco Conejero" locality of the Villar del Arzobispo Formation in Riodeva (Teruel, Spain). The remains were assigned to Dacentrurus armatus and consist of four vertebral centra, specimens MAP-4488-4491, from a single individual, two of which are cervical vertebrae, the third is dorsal, and the last is caudal. This discovery was considered significant because it would demonstrate both the intra-specific variability of Dacentrurus armatus, and the strong prevalence of Dacentrurus in the Iberian range during the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary, approximately 145 million years ago.[18] However, new paratype material of Miragaia described in 2019 shows stronger affinities to the Villar del Arzobispo material than the holotype material of Dacentrurus.[23]

Description

Dacentrurus was one of the largest species of stegosaur along with Stegosaurus, with some specimens have been estimated to reach 8–9 metres (26–30 ft) in length, 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) in hip height and 5 metric tons (5.5 short tons) in body mass.[24][25] For a stegosaur, the gut was especially broad,[25] and a massive rump is also indicated by exceptionally wide dorsal vertebrae centra.[14] The hindlimb was rather short,[25] but the forelimb relatively long, largely because of a long lower arm.[14]

Although Dacentrurus is considered to have the same proportions as Stegosaurus, its plate and spike configuration is known to be rather different, as it probably had both two rows of small plates on its neck and two rows of longer spikes along its tail.[26] The holotype specimen of Dacentrurus armatus contained a small blunt asymmetrical neck plate and also included a tail spike which could have been part of a thagomizer. The tail spike had sharp cutting edges on its front and rear side. Dacentrurus has sometimes been portrayed with a spike growing near the shoulder, similarly to a Kentrosaurus. Whether this portrayal is accurate or not is not yet determined.

Phylogeny

Dacentrurus was the first stegosaur of which good remains had ever been discovered; earlier finds as Paranthodon, Regnosaurus and Craterosaurus were too limited to be directly recognisable as representing a distinctive new group. Owen therefore was unable to closely relate his Omosaurus to other species but was aware it represented a member of the Dinosauria. In 1888 Richard Lydekker named a family Omosauridae, but this name fell into disuse once it was realised that Omosaurus was preoccupied. In the twentieth century Dacentrurus was usually assigned to the Stegosauridae.

Earlier often considered to have been a rather basal stegosaurid, Dacentrurus was by more extensive cladistic analyses in 2008 and 2010 shown to be relatively derived, forming the clade Dacentrurinae with its sister species Miragaia longicollum. The Dacentrurinae were the sister group of Stegosaurus (Stegosaurinae sensu Sereno).[27] The following cladogram shows the position of Dacentrurus armatus within the Thyreophora according to Maidment (2010):[12]

| Thyreophora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ Davis, W., 1876, "On the exhumation and development of a large reptile (Omosaurus armatus, Owen), from the Kimmeridge Clay, Swindon, Wilts.", Geological Magazine, 3: 193–197

- ↑ R. Owen, 1875, Monographs on the fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic formations. Part II. (Genera Bothriospondylus, Cetiosaurus, Omosaurus). The Palaeontographical Society, London 1875: 15-93

- ↑ R. Owen, 1877, Monographs on the fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic formations. Part III. (Omosaurus). The Palaeontographical Society, London 1877 :95-97

- ↑ J. W. Hulke, 1887, "Note on some dinosaurian remains in the collection of A. Leeds, Esq, of Eyebury, Northamptonshire", Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 43: 695-702

- ↑ Seeley, H. G., 1893, "Omosaurus phillipsi", Yorkshire Philosophical Society, Annual Report 1892, p. 52-57

- ↑ Seeley, H. G., 1901, (in Huene, F.): Centralblatt für Minerologie, Geologie und Paläontologie 1901, p. 718

- ↑ Huene, F. von, 1910, "Über den altesten Rest von Omosaurus (Dacenturus) im englischen Dogger", Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, 1910(1): 75-78

- ↑ Nopcsa, F., 1911, "Omosaurus lennieri, un nouveau Dinosaurien du Cap de la Hève", Bulletin de la Société Geologique de Normandie 30: 23-42

- ↑ J. Leidy, 1856, "Notice of remains of extinct vertebrated animals discovered by Professor E. Emmons", Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 8: 255-257

- ↑ F.A. Lucas, 1902, "Paleontological notes. The generic name Omosaurus: A new generic name for Stegosaurus marshi", Science, new series 16(402): 435

- ↑ Hennig, E., 1915, Stegosauria: Fossilium Catalogus I, Animalia pars 9, p. 1-16

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Maidment, S. C. R., 2010, "Stegosauria: a historical review of the body fossil record and phylogenetic relationships", Swiss Journal of Geosciences 103(2): 199-210

- ↑ Galton, P. M. and Powell, H. P., 1983, "Stegosaurian dinosaurs from the Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) of England, the earliest record of the family Stegosauridae", Geobios, 16: 219–229

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Galton, Peter M.; Upchurch, Paul, 2004, "Stegosauria" In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 344-345

- ↑ P. M. Galton. 1990. Stegosauria. The Dinosauria, D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmólska (editors), University of California Press, Berkeley 435-455

- ↑ Ulansky, R. E., 2014. Evolution of the stegosaurs (Dinosauria; Ornithischia). Dinologia, 35 pp. [in Russian]. [DOWNLOAD PDF] http://dinoweb.narod.ru/Ulansky_2014_Stegosaurs_evolution.pdf.

- ↑ Ronan Allain, Romain Vullo, Lee Rozada, Jérémy Anquetin, Renaud Bourgeais, et al.. Vertebrate paleobiodiversity of the Early Cretaceous (Berriasian) Angeac-Charente Lagerstätte (southwestern France): implications for continental faunal turnover at the J/K boundary. Geodiversitas, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle Paris, In press. ffhal-03264773f

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Alberto Cobos and Francisco Gascó. (2013) New vertebral remains of the stegosaurian dinosaur Dacentrurus from Riodeva (Teruel, Spain). Geogaceta, 53, 17-20.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Galton P.M. (1985) "British plated dinosaurs (Ornithischia, Stegosauridae), Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 5: 211-254

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Galton, Peter M.; Upchurch, Paul (2004). "Stegosauria (Table 16.1)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 344-345. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ Galton, P.M., 1981, "A juvenile stegosaurian dinosaur ‘‘Astrodon pusillus’’ from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal, with comments on Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous biogeography", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1: 245–256

- ↑ Maidment, S.C.R., Norman, D.B., Barrett, P.M., & Upchurch, P., 2008, "Systematics and phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)", Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 6: 367–407

- ↑ Costa, Francisco; Mateus, Octávio (2019-11-13). Joger, Ulrich. ed. "Dacentrurine stegosaurs (Dinosauria): A new specimen of Miragaia longicollum from the Late Jurassic of Portugal resolves taxonomical validity and shows the occurrence of the clade in North America" (in en). PLOS ONE 14 (11): e0224263. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224263. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 31721771. Bibcode: 2019PLoSO..1424263C.

- ↑ Cobos, A.; Royo-Torres, R.; Luque, L.; Alcalá, L.; Mampel, L. (2010). "An Iberian stegosaurs paradise: The Villar del Arzobispo Formation (Tithonian–Berriasian) in Teruel (Spain)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 293 (1–2): 223–226. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.05.024.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 223

- ↑ Lessem, Don (2003). Scholastic Dinosaurs A-Z. Scholastic Inc.. pp. 67. ISBN 978-0-439-16591-4.

- ↑ Mateus, Octávio; Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Christiansen, Nicolai A. (2009). "A new long-necked 'sauropod-mimic' stegosaur and the evolution of the plated dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276 (1663): 1815–1821. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1909. PMID 19324778.

Further reading

- Benton, M. J.; Spencer, P. S. (1995). Fossil Reptiles of Great Britain. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-62040-9.

External links

- Natural History Museum site on Dacentrurus

- dulops.net on Dacentrurus (in Spanish)

- Discussion on the claimed small size of Dacentrurus

Wikidata ☰ Q131760 entry

|