Biology:Functional specialization (brain)

In neuroscience, functional specialization is a theory which suggests that different areas in the brain are specialized for different functions.[1][2]

Historical origins

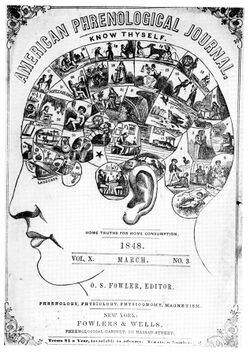

Phrenology, created by Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim (1776–1832) and best known for the idea that one's personality could be determined by the variation of bumps on their skull, proposed that different regions in one's brain have different functions and may very well be associated with different behaviours.[1][2] Gall and Spurzheim were the first to observe the crossing of pyramidal tracts, thus explaining why lesions in one hemisphere are manifested in the opposite side of the body. However, Gall and Spurzheim did not attempt to justify phrenology on anatomical grounds. It has been argued that phrenology was fundamentally a science of race. Gall considered the most compelling argument in favor of phrenology the differences in skull shape found in sub-Saharan Africans and the anecdotal evidence (due to scientific travelers and colonists) of their intellectual inferiority and emotional volatility. In Italy, Luigi Rolando carried out lesion experiments and performed electrical stimulation of the brain, including the Rolandic area.

Phineas Gage became one of the first lesion case studies in 1848 when an explosion drove a large iron rod completely through his head, destroying his left frontal lobe. He recovered with no apparent sensory, motor, or gross cognitive deficits, but with behaviour so altered that friends described him as "no longer being Gage," suggesting that the damaged areas are involved in "higher functions" such as personality.[3] However, Gage's mental changes are usually grossly exaggerated in modern presentations.

Subsequent cases (such as Broca's patient Tan) gave further support to the doctrine of specialization.

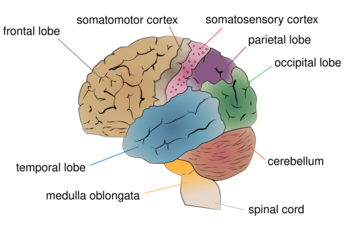

In the XX century, in the process of treating epilepsy, Wilder Penfield produced maps of the location of various functions (motor, sensory, memory, vision) in the brain.[4][5]

Major theories of the brain

Currently, there are two major theories of the brain's cognitive function. The first is the theory of modularity. Stemming from phrenology, this theory supports functional specialization, suggesting the brain has different modules that are domain specific in function. The second theory, distributive processing, proposes that the brain is more interactive and its regions are functionally interconnected rather than specialized. Each orientation plays a role within certain aims and tend to complement each other (see below section `Collaboration´).

Modularity

The theory of modularity suggests that there are functionally specialized regions in the brain that are domain specific for different cognitive processes.[6] Jerry Fodor expanded the initial notion of phrenology by creating his Modularity of the Mind theory. The Modularity of the Mind theory indicates that distinct neurological regions called modules are defined by their functional roles in cognition. He also rooted many of his concepts on modularity back to philosophers like Descartes, who wrote about the mind being composed of "organs" or "psychological faculties". An example of Fodor's concept of modules is seen in cognitive processes such as vision, which have many separate mechanisms for colour, shape and spatial perception.[7]

One of the fundamental beliefs of domain specificity and the theory of modularity suggests that it is a consequence of natural selection and is a feature of our cognitive architecture. Researchers Hirschfeld and Gelman propose that because the human mind has evolved by natural selection, it implies that enhanced functionality would develop if it produced an increase in "fit" behaviour. Research on this evolutionary perspective suggests that domain specificity is involved in the development of cognition because it allows one to pinpoint adaptive problems.[8]

An issue for the modular theory of cognitive neuroscience is that there are cortical anatomical differences from person to person. Although many studies of modularity are undertaken from very specific lesion case studies, the idea is to create a neurological function map that applies to people in general. To extrapolate from lesion studies and other case studies this requires adherence to the universality assumption, that there is no difference, in a qualitative sense, between subjects who are intact neurologically. For example, two subjects would fundamentally be the same neurologically before their lesions, and after have distinctly different cognitive deficits. Subject 1 with a lesion in the "A" region of the brain may show impaired functioning in cognitive ability "X" but not "Y", while subject 2 with a lesion in area "B" demonstrates reduced "Y" ability but "X" is unaffected; results like these allow inferences to be made about brain specialization and localization, also known as using a double dissociation.[6]

The difficulty with this theory is that in typical non-lesioned subjects, locations within the brain anatomy are similar but not completely identical. There is a strong defense for this inherent deficit in our ability to generalize when using functional localizing techniques (fMRI, PET etc.). To account for this problem, the coordinate-based Talairach and Tournoux stereotaxic system is widely used to compare subjects' results to a standard brain using an algorithm. Another solution using coordinates involves comparing brains using sulcal reference points. A slightly newer technique is to use functional landmarks, which combines sulcal and gyral landmarks (the groves and folds of the cortex) and then finding an area well known for its modularity such as the fusiform face area. This landmark area then serves to orient the researcher to the neighboring cortex.[9]

Future developments for modular theories of neuropsychology may lie in "modular psychiatry". The concept is that a modular understanding of the brain and advanced neuro-imaging techniques will allow for a more empirical diagnosis of mental and emotional disorders. There has been some work done towards this extension of the modularity theory with regards to the physical neurological differences in subjects with depression and schizophrenia, for example. Zielasek and Gaeble have set out a list of requirements in the field of neuropsychology in order to move towards neuropsychiatry:

- To assemble a complete overview of putative modules of the human mind

- To establish module-specific diagnostic tests (specificity, sensitivity, reliability)

- To assess how far individual modules, sets of modules or their connections are affected in certain psychopathological situations

- To probe novel module-specific therapies like the facial affect recognition training or to retrain access to context information in the case of delusions and hallucinations, in which "hyper-modularity" may play a role [10]

Research in the study of brain function can also be applied to cognitive behaviour therapy. As therapy becomes increasingly refined, it is important to differentiate cognitive processes in order to discover their relevance towards different patient treatments. An example comes specifically from studies on lateral specialization between the left and right cerebral hemispheres of the brain. The functional specialization of these hemispheres are offering insight on different forms of cognitive behaviour therapy methods, one focusing on verbal cognition (the main function of the left hemisphere) and the other emphasizing imagery or spatial cognition (the main function of the right hemisphere).[11] Examples of therapies that involve imagery, requiring right hemisphere activity in the brain, include systematic desensitization[12] and anxiety management training.[13] Both of these therapy techniques rely on the patient's ability to use visual imagery to cope with or replace patients symptoms, such as anxiety. Examples of cognitive behaviour therapies that involve verbal cognition, requiring left hemisphere activity in the brain, include self-instructional training[11] and stress inoculation.[14] Both of these therapy techniques focus on patients' internal self-statements, requiring them to use vocal cognition. When deciding which cognitive therapy to employ, it is important to consider the primary cognitive style of the patient. Many individuals have a tendency to prefer visual imagery over verbalization and vice versa. One way of figuring out which hemisphere a patient favours is by observing their lateral eye movements. Studies suggest that eye gaze reflects the activation of cerebral hemisphere contralateral to the direction. Thus, when asking questions that require spatial thinking, individuals tend to move their eyes to the left, whereas when asked questions that require verbal thinking, individuals usually move their eyes to the right.[15] In conclusion, this information allows one to choose the optimal cognitive behaviour therapeutic technique, thereby enhancing the treatment of many patients.

Areas representing modularity in the brain

Fusiform face area

One of the most well known examples of functional specialization is the fusiform face area (FFA). Justine Sergent was one of the first researchers that brought forth evidence towards the functional neuroanatomy of face processing. Using positron emission tomography (PET), Sergent found that there were different patterns of activation in response to the two different required tasks, face processing verses object processing.[16] These results can be linked with her studies of brain-damaged patients with lesions in the occipital and temporal lobes. Patients revealed that there was an impairment of face processing but no difficulty recognizing everyday objects, a disorder also known as prosopagnosia.[16] Later research by Nancy Kanwisher using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), found specifically that the region of the inferior temporal cortex, known as the fusiform gyrus, was significantly more active when subjects viewed, recognized and categorized faces in comparison to other regions of the brain. Lesion studies also supported this finding where patients were able to recognize objects but unable to recognize faces. This provided evidence towards domain specificity in the visual system, as Kanwisher acknowledges the Fusiform Face Area as a module in the brain, specifically the extrastriate cortex, that is specialized for face perception.[17]

Visual area V4 and V5

While looking at the regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF), using PET, researcher Semir Zeki directly demonstrated functional specialization within the visual cortex known as visual modularity, first in the monkey[18] and then in the human visual brain. He localized regions involved specifically in the perception of colour and vision motion, as well as of orientation (form).[19] For colour, visual area V4 was located when subjects were shown two identical displays, one being multicoloured and the other shades of grey.[20] This was further supported from lesion studies where individuals were unable to see colours after damage, a disorder known as achromatopsia.[21][22] Combining PET and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), subjects viewing a moving checker board pattern verses a stationary checker board pattern located visual area V5, which is now considered to be specialized for vision motion. (Watson et al., 1993) This area of functional specialization was also supported by lesion study patients whose damage caused cerebral motion blindness,[23] a condition now referred to as cerebral akinetopsia[24]

Frontal lobes

Studies have found the frontal lobes to be involved in the executive functions of the brain, which are higher level cognitive processes.[25] This control process is involved in the coordination, planning and organizing of actions towards an individual's goals. It contributes to such things as one's behaviour, language and reasoning. More specifically, it was found to be the function of the prefrontal cortex,[26] and evidence suggest that these executive functions control processes such as planning and decision making, error correction and assisting overcoming habitual responses. Miller and Cummings used PET and functional magnetic imaging (fMRI) to further support functional specialization of the frontal cortex. They found lateralization of verbal working memory in the left frontal cortex and visuospatial working memory in the right frontal cortex. Lesion studies support these findings where left frontal lobe patients exhibited problems in controlling executive functions such as creating strategies.[27] The dorsolateral, ventrolateral and anterior cingulate regions within the prefrontal cortex are proposed to work together in different cognitive tasks, which is related to interaction theories. However, there has also been evidence suggesting strong individual specializations within this network.[25] For instance, Miller and Cummings found that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is specifically involved in the manipulation and monitoring of sensorimotor information within working memory.[27]

Right and left hemispheres

During the 1960s, Roger Sperry conducted a natural experiment on epileptic patients who had previously had their corpora callosa cut. The corpus callosum is the area of the brain dedicated to linking both the right and left hemisphere together. Sperry et al.'s experiment was based on flashing images in the right and left visual fields of his participants. Because the participant's corpus callosum was cut, the information processed by each visual field could not be transmitted to the other hemisphere. In one experiment, Sperry flashed images in the right visual field (RVF), which would subsequently be transmitted to the left hemisphere (LH) of the brain. When asked to repeat what they had previously seen, participants were fully capable of remembering the image flashed. However, when the participants were then asked to draw what they had seen, they were unable to. When Sperry et al. flashed images in the left visual field (LVF), the information processed would be sent to the right hemisphere (RH) of the brain. When asked to repeat what they had previously seen, participants were unable to recall the image flashed, but were very successful in drawing the image. Therefore, Sperry concluded that the left hemisphere of the brain was dedicated to language as the participants could clearly speak the image flashed. On the other hand, Sperry concluded that the right hemisphere of the brain was involved in more creative activities such as drawing.[28]

Parahippocampal place area

Located in the parahippocampal gyrus, the parahippocampal place area (PPA) was coined by Nancy Kanwisher and Russell Epstein after an fMRI study showed that the PPA responds optimally to scenes presented containing a spatial layout, minimally to single objects and not at all to faces.[29] It was also noted in this experiment that activity remains the same in the PPA when viewing a scene with an empty room or a room filled with meaningful objects. Kanwisher and Epstein proposed "that the PPA represents places by encoding the geometry of the local environment".[29] In addition, Soojin Park and Marvin Chun posited that activation in the PPA is viewpoint specific, and so responds to changes in the angle of the scene. In contrast, another special mapping area, the retrosplenial cortex (RSC), is viewpoint invariant or does not change response levels when views change.[30] This perhaps indicates a complementary arrangement of functionally and anatomically separate visual processing brain areas.

Extrastriate body area

Located in the lateral occipitotemporal cortex, fMRI studies have shown the extrastriate body area (EBA) to have selective responding when subjects see human bodies or body parts, implying that it has functional specialization. The EBA does not optimally respond to objects or parts of objects but to human bodies and body parts, a hand for example. In fMRI experiments conducted by Downing et al. participants were asked to look at a series of pictures. These stimuli includes objects, parts of objects (for example just the head of a hammer), figures of the human body in all sorts of positions and types of detail (including line drawings or stick men), and body parts (hands or feet) without any body attached. There was significantly more blood flow (and thus activation) to human bodies, no matter how detailed, and body parts than to objects or object parts.[31]

Distributive processing

The cognitive theory of distributed processing suggests that brain areas are highly interconnected and process information in a distributed manner.

A remarkable precedent of this orientation is the research of Justo Gonzalo on brain dynamics [32] where several phenomena that he observed could not be explained by the traditional theory of localizations. From the gradation he observed between different syndromes in patients with different cortical lesions, this author proposed in 1952 a functional gradients model,[33] which permits an ordering and an interpretation of multiple phenomena and syndromes. The functional gradients are continuous functions through the cortex describing a distributed specificity, so that, for a given sensory system, the specific gradient, of contralateral character, is maximum in the corresponding projection area and decreases in gradation towards more "central" zone and beyond so that the final decline reaches other primary areas. As a consequence of the crossing and overlapping of the specific gradients, in the central zone where the overlap is greater, there would be an action of mutual integration, rather nonspecific (or multisensory) with bilateral character due to the corpus callosum. This action would be maximum in the central zone and minimal towards the projection areas. As the author stated (p. 20 of the English translation[33]) "a functional continuity with regional variation is then offered, each point of the cortex acquiring different properties but with certain unity with the rest of the cortex. It is a dynamic conception of quantitative localizations". A very similar gradients scheme was proposed by Elkhonon Goldberg in 1989 [34]

Other researchers who provide evidence to support the theory of distributive processing include Anthony McIntosh and William Uttal, who question and debate localization and modality specialization within the brain. McIntosh's research suggests that human cognition involves interactions between the brain regions responsible for processes sensory information, such as vision, audition, and other mediating areas like the prefrontal cortex. McIntosh explains that modularity is mainly observed in sensory and motor systems, however, beyond these very receptors, modularity becomes "fuzzier" and you see the cross connections between systems increase.[35] He also illustrates that there is an overlapping of functional characteristics between the sensory and motor systems, where these regions are close to one another. These different neural interactions influence each other, where activity changes in one area influence other connected areas. With this, McIntosh suggest that if you only focus on activity in one area, you may miss the changes in other integrative areas.[35] Neural interactions can be measured using analysis of covariance in neuroimaging. McIntosh used this analysis to convey a clear example of the interaction theory of distributive processing. In this study, subjects learned that an auditory stimulus signalled a visual event. McIntosh found activation (an increase blood flow), in an area of the occipital cortex, a region of the brain involved in visual processing,[36] when the auditory stimulus was presented alone. Correlations between the occipital cortex and different areas of the brain such as the prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex and superior temporal cortex showed a pattern of co-variation and functional connectivity.[37]

Uttal focusses on the limits of localizing cognitive processes in the brain. One of his main arguments is that since the late 1990s, research in cognitive neuroscience has forgotten about conventional psychophysical studies based on behavioural observation. He believes that current research focusses on the technological advances of brain imaging techniques such as MRI and PET scans. Thus, he further suggest that this research is dependent on the assumptions of localization and hypothetical cognitive modules that use such imaging techniques to pursuit these assumptions. Uttal's major concern incorporates many controversies with the validly, over-assumptions and strong inferences some of these images are trying to illustrate. For instance, there is concern over the proper utilization of control images in an experiment. Most of the cerebrum is active during cognitive activity, therefore the amount of increased activity in a region must be greater when compared to a controlled area. In general, this may produce false or exaggerated findings and may increase potential tendency to ignore regions of diminished activity which may be crucial to the particular cognitive process being studied.[38] Moreover, Uttal believes that localization researchers tend to ignore the complexity of the nervous system. Many regions in the brain are physically interconnected in a nonlinear system, hence, Uttal believes that behaviour is produced by a variety of system organizations.[38]

Collaboration

The two theories, modularity and distributive processing, can also be combined. By operating simultaneously, these principles may interact with each other in a collaborative effort to characterize the functioning of the brain. Fodor himself, one of the major contributors to the modularity theory, appears to have this sentiment. He noted that modularity is a matter of degrees, and that the brain is modular to the extent that it warrants studying it in regards to its functional specialization.[7] Although there are areas in the brain that are more specialized for cognitive processes than others, the nervous system also integrates and connects the information produced in these regions. In fact, the proposed distributive scheme of the functional cortical gradientes by J. Gonzalo[33] already tries to join both concepts modular and distributive: regional heterogeneity should be a definitive acquisition (maximum specificity in the projection paths and primary areas), but the rigid separation between projection and association areas would be erased through the continuous functions of gradient.

The collaboration between the two theories not only would provide a more unified perception and understanding of the world but also make available the ability to learn from it.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Flourens, M. J. P. (1824) Recherces experimentales sur les propretes et les fonctions du systeme nerveux dans les animaux vertebres. Paris: J.B. Balliere.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lashley, K. S. (1929) Brain mechanisms and intelligence. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- ↑ Blair., R. (2004) The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behaviour Brain and Cognition 55 pp. 198–208

- ↑ Resnick, Brian (26 January 2018). "Wilder Penfield redrew the map of the brain — by opening the heads of living patients". Vox. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/1/26/16932476/wilder-penfield-brain-surgery-epilepsy-google-doodle.

- ↑ "Penfield – A great explorer of psyche-soma-neuroscience". Indian Journal of Psychiatry 53 (3): 276–278. 2011. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.86826. PMID 22135453.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Caramazza, A., Coltheart, M. Cognitive Neuropsychology twenty years on. Cognitive Neuropsychology. Psychology Press. 23(1), 3–12. (2006)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fodor, J. A. (1983). The Modularity of the Mind. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (pg 2–47)

- ↑ Hirschfeld, L. A., Gelman, S. A. (1994) Mapping the Mind: Domain specificity in cognition and culture. Cambridge University Press pg 37–169

- ↑ Saxe, R., Brett, M., Kanwisher, N. Divide and conquer: A defense of functional localizers. Neuroimage. 2006.

- ↑ Zielasek, J., Gaeble W. (2008) Modern modularity and the road towards modular psychiatry. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 258, 60–65.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Tucker, D.M., Shearer, S.L., and Murray, J.D. (1977). Hemispheric Specialization and Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, VoL 1, pp. 263–273

- ↑ Goldfried, M. R. Systematic desensitization as training in self-control. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1971, 37, 228–234.

- ↑ Suinn, R. M., & Richardson, F. Anxiety management training: A nonspecific behavior therapy program for anxiety control. Behavior Therapy, 1971, 2, 498–510

- ↑ Novaco, R. W. (1977). Stress inoculation: A cognitive therapy for anger and its application to a case of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Vol 45(4), 600–608.

- ↑ Kocel, K., Galin, D., Ornstein, R., & Merrin, E. L. Lateral eye movements and cognitive mode. Psychonomic Science, 1972, 27, 223–224.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Sergent, J., Signoret, J.L. (1992) Functional and anatomical decomposition of face processing: evidence from prosopagnosia and PET study of normal subject. The Royal Society. 335, 55–62

- ↑ Kanwisher, N., McDermott, J., Chun, M. (1997). The Fusiform Face Area: A Module in Human Extrastriate Cortex Specialized for Face Perception. The Journal of Neuroscience, 17(11):4302–4311

- ↑ Zeki, S. M. (August 1978). "Functional specialisation in the visual cortex of the rhesus monkey". Nature 274 (5670): 423–428. doi:10.1038/274423a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 97565. Bibcode: 1978Natur.274..423Z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/274423a0.

- ↑ Zeki, S M (1978-04-01). "Uniformity and diversity of structure and function in rhesus monkey prestriate visual cortex.". The Journal of Physiology 277 (1): 273–290. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012272. ISSN 0022-3751. PMID 418176. PMC 1282389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012272.

- ↑ Zeki, S., et al. (1991). A direct demonstration of functional specialization in human visual cortex. United Kingdom, London. Journal of Neuroscience, Vol 11, 641–649

- ↑ ZEKI, S. (1990). "A Century of Cerebral Achromatopsia". Brain 113 (6): 1721–1777. doi:10.1093/brain/113.6.1721. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 2276043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/113.6.1721.

- ↑ Pearlman AL, Birch J, Meadows JC (1979) Cerebral color blindness: an acquired defect in hue discrimination. Ann Neurol 5:253–261.

- ↑ ZIHL, J.; VON CRAMON, D.; MAI, N. (1983). "Selective Disturbance of Movement Vision After Bilateral Brain Damage". Brain 106 (2): 313–340. doi:10.1093/brain/106.2.313. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 6850272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/106.2.313.

- ↑ ZEKI, S. (1991). "Cerebral Akinetopsia (Vusyak Nituib Vkubdbess) A Review". Brain 114 (4): 2021. doi:10.1093/brain/114.4.2021. ISSN 0006-8950.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Duncan, J., & Owen, A. (2000). Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Elsevier Science.

- ↑ Fuster, J. (2008). The Prefrontal Cortex. Elsevier. (pg 178–353)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Miller, B., Cummings, J. (2007) The Human Frontal Lobes: Functions and Disorders. The Guilford Press, New York and London.(pg 68–77)

- ↑ "The Split Brain Experiments". Nobelprize.org. 4 Oct 2011 http://www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/split-brain/background.html

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Epstien, R., & Kanwisher, N. (1998). A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Amherst Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- ↑ Park, S., Chun, M. (2009) Different roles of the parahippocampal place area (PPA) and retrosplenial cortex (RSC)in panoramic scene perception. NeuroImage 47, 1747–1756.

- ↑ Downing, P., Jiang, Y., Shuman, M., Kanwisher, N. (2001) A cortical area selective for visual processing of the human body. Science, 293.

- ↑ Gonzalo, J. (1945, 1950, 1952, 2010, 2021). Dinámica Cerebral, Open Access. Edición facsímil 2010 del Vol. 1 1945, Vol. 2 1950 (Madrid: Inst. S. Ramón y Cajal, CSIC), Suplemento I 1952 (Trab. Inst. Cajal Invest. Biol.) y 1ª ed. Suplemento II 2010. Red Temática en Tecnologías de Computación Artificial/Natural (RTNAC) y Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (USC). ISBN 978-84-9887-458-7. English translation of Vol. 1 1945 (2021) Open Access. English translation of the article of 1952 (2015) Open Access.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Gonzalo, J. (1952). "Las funciones cerebrales humanas según nuevos datos y bases fisiológicas. Una introducción a los estudios de Dinámica Cerebral". Trabajos del Inst. Cajal de Investigaciones Biológicas XLIV: pp. 95–157. Complete English translation, Open Access.

- ↑ Goldberg, E. (1989). "Gradiental approach to neocortical functional organization". J. Clinical and Experimental Neurophysiology 11 489-517.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 McIntosh, A. R. (1999). Mapping Cognition to the Brain Through Neural Interactions. University of Toronto, Canada. Psychology Press, 523–548

- ↑ Zeki, S. (1993). A vision of the brain. Cambridge, MA, US: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- ↑ McIntosh, A. R., Cabeza, R. E., and Lobaugh, N., J. (1998). Analysis of Neural Interactions Explains the Activation of Occipital Cortex by an Auditory Stimulus. The Journal of Neurophysiology Vol. 80 No. 5, pp. 2790–2796

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Uttal, W. R. (2002). Précis of The New Phrenology: The Limits of Localizing Cognitive Processes in the Brain. Department of Industrial Engineering, Arizona State University, USA.

|