Biology:Hadrosaurid

| Hadrosaurids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus, Field Museum of Natural History | |

| |

| Mounted skeleton of Edmontosaurus annectens, Oxford University Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Clade: | †Hadrosauromorpha |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae Cope, 1869 |

| Type species | |

| †Hadrosaurus foulkii Leidy, 1858

| |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Hadrosaurids (Greek: ἁδρός, hadrós, "stout, thick"), or duck-billed dinosaurs, are members of the ornithischian family Hadrosauridae. This group is known as the duck-billed dinosaurs for the flat duck-bill appearance of the bones in their snouts. The family, which includes ornithopods such as Edmontosaurus and Parasaurolophus, was a common herbivore in the Upper Cretaceous Period of what is now Asia, Europe, Antarctica, South America, and North America.[1] Hadrosaurids are descendants of the Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous iguanodontian dinosaurs and had a similar body layout. Like the rest of the ornithischians, these animals had a predentary bone and a pubic bone which was positioned backwards in the pelvis. Hadrosaurids are divided into two principal subfamilies: the lambeosaurines (Lambeosaurinae), which had hollow cranial crests or tubes, and the saurolophines, identified as hadrosaurines in most pre-2010 works (Saurolophinae or Hadrosaurinae), which lacked hollow cranial crests (solid crests were present in some forms). Saurolophines tended to be bulkier than lambeosaurines. Lambeosaurines included the aralosaurins, tsintaosaurins, lambeosaurins and parasaurolophins, while saurolophines included the brachylophosaurins, kritosaurins, saurolophins and edmontosaurins.

Hadrosaurids were facultative bipeds, with the young of some species walking mostly on two legs and the adults walking mostly on four.[2][3] Their jaws were evolved for grinding plants, with multiple rows of teeth replacing each other as the teeth wore down.[2]

Discoveries

Hadrosaurids were the first dinosaur family to be identified in North America - the first traces being found in 1855-1856 with the discovery of fossil teeth. Joseph Leidy examined the teeth, and erected the genera Trachodon and Thespesius (others included Troodon, Deinodon, and Palaeoscincus). One species was named Trachodon mirabilis. Ultimately, Trachodon included all sorts of cerapod dinosaurs, including ceratopsids, and is now considered an invalid genus. In 1858, the teeth were associated with Leidy's eponymous Hadrosaurus foulkii, which was named after the fossil hobbyist William Parker Foulke. More and more teeth were found, resulting in even more (now obsolete) genera.

When a second duck-bill skeleton was unearthed, Edward Drinker Cope incorrectly named it Diclonius mirabilis in 1883 instead of Trachodon mirabilis, but Trachodon, together with other poorly typed genera, was used more widely, and when Cope's famous "Diclonius mirabilis" skeleton was mounted at the American Museum of Natural History, it was labeled as a "Trachodont dinosaur". The duck-billed dinosaur family was then named Trachodontidae.

A very well preserved complete hadrosaurid specimen, AMNH 5060, (Edmontosaurus annectens) was recovered in 1908 by the fossil collector Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his three sons, in Converse County, Wyoming. Analyzed by Henry Osborn in 1912, it has come to be known as the "Trachodon mummy". This specimen's skin was almost completely preserved in the form of impressions.

Lawrence Lambe erected the genus Edmontosaurus ("lizard from Edmonton") in 1917 from a find in the lower Edmonton Formation (now Horseshoe Canyon Formation), Alberta. Hadrosaurid systematics were addressed in a 1942 monograph by Richard Swann Lull and Nelda Wright. They proposed the genus Anatosaurus for several species of dubious genera. Cope's famous mount at the AMNH became Anatosaurus copei. In 1990, Anatosaurus was moved to Edmontosaurus. One former Anatosaurus species was distinct enough from Edmontosaurus to be placed in a separate genus, named Anatotitan, so in 1990, the AMNH mount was relabelled Anatotitan copei.

Paleontologists have found a hadrosaurid leg bone in Paleocene rocks, but it was probably reworked from a Cretaceous source.[4]

One of the most complete fossilized specimens was found in 1999 in the Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota and is now nicknamed "Dakota". The hadrosaur fossil is so well preserved that scientists have been able to calculate its muscle mass and learn that it was more muscular than thought, probably giving it the ability to outrun predators, such as Tyrannosaurus rex. Dakota is more than fossilized bones, it is a fossilized mummy. It comes complete with skin (not merely skin impressions), ligaments, tendons, and possibly some internal organs. It is being analyzed in the world's largest CT scanner, operated by the Boeing Co.[5] The machine is usually used for detecting flaws in space shuttle engines and other large objects, but previously none as large as this. Researchers hope the technology will help them learn more about the fossilized insides of the creature. They also found a gap of about a centimeter between each vertebra, indicating that a disk or other material may have existed between them, allowing more flexibility and meaning the animal was actually longer than what is shown in a museum.[6] Skin impressions have been found from the following hadrosaurs: Edmontosaurus annectens, Corythosaurus casuarius, Brachylophosaurus canadensis, Gryposaurus notabilis, Parasaurolophus walkeri, Lambeosaurus magnicristatus, Lambeosaurus lambei, Saurolophus osborni, Magnapaulia laticaudus and, Saurolophus angustirostris.[7]

Classification

The family Hadrosauridae was first used by Edward Drinker Cope in 1869. Since its creation, a major division has been recognized in the group between the (generally crested) subfamily Lambeosaurinae and (generally crestless) subfamily Saurolophinae (or Hadrosaurinae). Phylogenetic analysis has increased the resolution of hadrosaurid relationships considerably (see Phylogeny below), leading to the widespread usage of tribes (a taxonomic unit below subfamily) to describe the finer relationships within each group of hadrosaurids. Recent phylogenies also support the monophyly of both the Saurolophinae and the Lambeosaurinae.[8] However, some hadrosaurid tribes commonly recognized in online sources have not yet been formally defined or seen wide use in the literature. Several were briefly mentioned under informal names, but not named as such, in the first edition of The Dinosauria. In this 1990 reference, "gryposaurs" included Aralosaurus, Gryposaurus, Hadrosaurus, and Kritosaurus; "brachylophosaurs" included Brachylophosaurus and Maiasaura; "saurolophs" included Lophorhothon, Prosaurolophus, and Saurolophus; and "edmontosaurs" included Edmontosaurus, and Shantungosaurus.[9]

Lambeosaurines have also been traditionally split into Parasaurolophini and Lambeosaurini.[10] These terms entered the formal literature in Evans and Reisz's 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus. Lambeosaurini is defined as all taxa more closely related Lambeosaurus lambei than to Parasaurolophus walkeri, and Parasaurolophini as all those taxa closer to P. walkeri than to L. lambei. In recent years Tsintaosaurini (Tsintaosaurus + Pararhabdodon) and Aralosaurini (Aralosaurus + Canardia) have also emerged.[11]

The use of the term Hadrosaurinae was questioned in a comprehensive study of hadrosaurid relationships by Albert Prieto-Márquez in 2010. Prieto-Márquez noted that, though the name Hadrosaurinae had been used for the clade of mostly crestless hadrosaurids by nearly all previous studies, its type species, Hadrosaurus foulkii, has almost always been excluded from the clade that bears its name, in violation of the rules for naming animals set out by the ICZN. Prieto-Márquez defined Hadrosaurinae as just the lineage containing H. foulkii, and used the name Saurolophinae instead for the traditional grouping.[8]

Phylogeny

Hadrosauridae was first defined as a clade, by Forster, in a 1997 abstract, as simply "Lambeosaurinae plus Hadrosaurinae and their most recent common ancestor". In 1998, Paul Sereno defined the clade Hadrosauridae as the most inclusive possible group containing Saurolophus (a well-known saurolophine) and Parasaurolophus (a well-known lambeosaurine), later emending the definition to include Hadrosaurus, the type genus of the family, which ICZN rules state must be included, despite its status as a nomen dubium. According to Horner et al. (2004), Sereno's definition would place a few other well-known hadrosaurs (such as Telmatosaurus and Bactrosaurus) outside the family, which led them to define the family to include Telmatosaurus by default. Prieto-Marquez reviewed the phylogeny of Hadrosauridae in 2010, including many taxa potentially within the family.[8]

Below is a cladogram from Prieto-Marquez et al. 2016. This cladogram is a recent modification of the original 2010 analysis, including more characters and taxa. The resulting cladistic tree of their analysis was resolved using Maximum-Parsimony. 61 hadrosauroid species were included, characterized for 273 morphological features: 189 for cranial features and 84 for postcranial features. When characters had multiple states that formed an evolutionary scheme, they were ordered to account for the evolution of one state into the next. The final tree was run through TNT version 1.0.[12]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Characteristics

The most recognizable aspect of hadrosaur anatomy is the flattened and laterally stretched rostral bones, which gives the distinct duck-bill look, and some members of the hadrosaurs also had massive crests on their heads, probably for display.[8] In some genera, including Edmontosaurus, the whole front of the skull was flat and broadened out to form a beak, which was ideal for clipping leaves and twigs from the forests of Asia, Europe and North America. However, the back of the mouth contained thousands of teeth suitable for grinding food before it was swallowed. This has been hypothesized to have been a crucial factor in the success of this group in the Cretaceous compared to the sauropods.

Skin impressions of multiple hadrosaurs have been found.[7] From these impressions, the hadrosaurs were determined to be scaled, and not feathered like some dinosaurs of other groups.

In 2009, paleontologist Mark Purnell conducted a study into the chewing methods and diet of hadrosaurids from the Late Cretaceous. By analyzing hundreds of microscopic scratches on the teeth of a fossilized Edmontosaurus jaw, the team determined hadrosaurs had a unique way of eating unlike any creature living today. In contrast to a flexible lower jaw joint prevalent in today's mammals, hadrosaurs had a unique hinge between the upper jaws and the rest of its skull. The team found the dinosaur's upper jaws pushed outwards and sideways while chewing, as the lower jaw slid against the upper teeth.[13] This chewing method is called pleurokinesis. During pleurokinesis, the maxilla bones slide laterally outward from the mouth. This is accomplished with a hinge made of the joints between the premaxilla and maxilla bones and the lacrimal and prefrontal bones. Pleurokinesis allows for the teeth to more precisely grind against one another, for better shearing of plant material, and reduces the stress that chewing puts on the skull.[14] Analysis of the wear patterns of the teeth has provided further insight into how these animals may have fed. On the teeth, four different sets of wear patterns can be found that indicate the lower jaw would have moved directly up and down.[15] Furthermore, the wear patterns were parallel, revealing that the rows of teeth were extremely well aligned in the jaw.

Hadrosaurs, much like sauropods, are noted for having their manus united in a fleshy, often nail-less pad.[16]

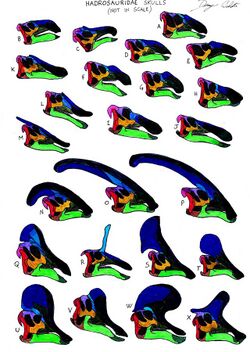

Cranial differences between subfamilies

The two major divisions of hadrosaurids are differentiated by their cranial ornamentation. While members of the Lambeosaurinae subfamily have hollow crests that differ depending on species, members of the Saurolophinae (Hadrosaurinae) subfamily have solid crests or none at all. Lambeosaurine crests had air chambers that may have produced a distinct sound and meant that their crests could have been used for both an audio and visual display.

Paleobiology

Diet

While studying the chewing methods of hadrosaurids in 2009, the paleontologists Vincent Williams, Paul Barrett, and Mark Purnell found that hadrosaurs likely grazed on horsetails and vegetation close to the ground, rather than browsing higher-growing leaves and twigs. This conclusion was based on the evenness of scratches on hadrosaur teeth, which suggested the hadrosaur used the same series of jaw motions over and over again.[15] As a result, the study determined that the hadrosaur diet was probably made of leaves and lacked the bulkier items, such as twigs or stems, that might have required a different chewing method and created different wear patterns.[17] However, Purnell said these conclusions were less secure than the more conclusive evidence regarding the motion of teeth while chewing.[13]

The hypothesis that hadrosaurs were likely grazers rather than browsers appears to contradict previous findings from preserved stomach contents found in the fossilized guts in previous hadrosaur studies.[13] The most recent such finding before the publication of the Purnell study was conducted in 2008, when a team led by University of Colorado at Boulder graduate student Justin S. Tweet found a homogeneous accumulation of millimeter-scale leaf fragments in the gut region of a well-preserved partially grown Brachylophosaurus.[18][19] As a result of that finding, Tweet concluded in September 2008 that the animal was likely a browser, not a grazer.[19] In response to such findings, Purnell said that preserved stomach contents are questionable because they do not necessarily represent the usual diet of the animal. The issue remains a subject of debate.[20]

Mallon et al. (2013) examined herbivore coexistence on the island continent of Laramidia, during the Late Cretaceous. It was concluded that hadrosaurids could reach low-growing trees and shrubs that were out of the reach of ceratopsids, ankylosaurs, and other small herbivores. Hadrosaurids were capable of feeding up to 2 m when standing quadrupedally, and up to 5 m bipedally.[21]

Coprolites (fossilized droppings) of some Late Cretaceous hadrosaurs show that the animals sometimes deliberately ate rotting wood. Wood itself is not nutritious, but decomposing wood would have contained fungi, decomposed wood material and detritus-eating invertebrates, all of which would have been nutritious.[22] Examination of hadrosaur coprolites from the Grand Staircase-Escalante indicates that shellfish such as crustaceans were also an important component of the hadrosaur diet.[23]

Reproduction

Neonate sized hadrosaur fossils have been documented in the scientific literature.[24] Tiny hadrosaur footprints have been discovered in the Blackhawk Formation of Utah.[24]

In the Dinosaur Park Formation

In a 2001 review of hadrosaur eggshell and hatchling material from Alberta's Dinosaur Park Formation, Darren Tanke and M. K. Brett-Surman concluded that hadrosaurs nested in both the ancient upland and lowlands of the formation's depositional environment. The upland nesting grounds may have been preferred by the less common hadrosaurs, like Brachylophosaurus and Parasaurolophus. However, the authors were unable to determine what specific factors shaped nesting ground choice in the formation's hadrosaurs. They suggested that behavior, diet, soil condition, and competition between dinosaur species all potentially influenced where hadrosaurs nested.[24]

Sub-centimeter fragments of pebbly-textured hadrosaur eggshell have been reported from the Dinosaur Park Formation. This eggshell is similar to the hadrosaur eggshell of Devil's Coulee in southern Alberta as well as that of the Two Medicine and Judith River Formations in Montana, United States. While present, dinosaur eggshell is very rare in the Dinosaur Park Formation and is only found in two different microfossil sites. These sites are distinguished by large numbers of pisidiid clams and other less common shelled invertebrates, like unionid clams and snails. This association is not a coincidence, as the invertebrate shells would have slowly dissolved and released enough basic calcium carbonate to protect the eggshells from naturally occurring acids that otherwise would have dissolved them and prevented fossilization.[24]

In contrast with eggshell fossils, the remains of very young hadrosaurs are somewhat common. Tanke has observed that an experienced collector could discover multiple juvenile hadrosaur specimens in a single day. The most common remains of young hadrosaurs in the Dinosaur Park Formation are dentaries, bones from limbs and feet, as well as vertebral centra. The material showed little or none of the abrasion that would have resulted from transport, meaning the fossils were buried near their point of origin. Bonebeds 23, 28, 47, and 50 are productive sources of young hadrosaur remains in the formation, especially bonebed 50. The bones of juvenile hadrosaurs and fossil eggshell fragments are not known to have been preserved in association with each other, despite both being present in the formation.[24]

Development

The limbs of the juvenile hadrosaurs are anatomically and proportionally similar to those of adult animals.[24] However, the joints often show "predepositional erosion or concave articular surfaces",[24] which was probably due to the cartilaginous cap covering the ends of the bones.[24] The pelvis of a young hadrosaur was similar to that of an older individual.[24]

Evidence suggests that young hadrosaurs would have walked on only their two hind legs, while adults would have walked on all four.[2] As the animal aged, the front limbs became more robust in order to take on weight, while the back legs became less robust as they transitioned to walking on all four legs.[2] Furthermore, the animals’ front limbs were shorter than their back limbs.[2]

Daily activity patterns

Comparisons between the scleral rings of several hadrosaur genera (Corythosaurus, Prosaurolophus, and Saurolophus) and modern birds and reptiles suggest that they may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals.[25]

Pathology

Spondyloarthropathy has been documented in the spine of a 78-million year old hadrosaurid.[citation needed] Other examples of pathologies in hadrosaurs include healed wounds from predators, such as those found in Edmontosaurus annectens, and tumors such as hemangiomas, desmoplastic fibroma, metastatic cancer, and osteoblastomas, found in genera such as Brachylophosaurus and Edmontosaurus.[26][27] Osteochondrosis is also commonly found in hadrosaurs.[28]

Ichnology

Tiny hadrosaur footprints have been discovered in the Blackhawk Formation of Utah.[24]

References

- ↑ Case, Judd A.; Martin, James E.; Chaney, Dan S.; Regurero, Marcelo; Marenssi, Sergio A.; Santillana, Sergio M.; Woodburne, Michael O. (25 September 2000). "The first duck-billed dinosaur (family Hadrosauridae) from Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20 (3): 612–614. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0612:tfdbdf2.0.co;2].

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Dilkes, David W. (2001). "An ontogenetic perspective on locomotion in the Late Cretaceous dinosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38 (8).

- ↑ Fiorillo, A.R.; Tykoski, R.S. (2016). "Small hadrosaur manus and pes tracks from the Lower Cantwell Formation (Upper Cretaceous) Denali National Park, Alaska: implications for locomotion in juvenile hadrosaurs". Palaios 31 (10): 479–482. doi:10.2110/palo.2016.049. http://palaios.geoscienceworld.org/content/31/10/479.

- ↑ Fassett, J, Zielinski, R.A., and Budahn, J.R. (2002). Dinosaurs that did not die; evidence for Paleocene dinosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. In: Koeberl, C., and MacLeod, K. (eds.). Catastrophic events and mass extinctions: impacts and beyond. Special Paper – Geological Society of America 356:307-336.

- ↑ (Reuters News) "Mummified dinosaur reveals surprises: scientists" 3 December 2007.

- ↑ Schmid, Randolph (2007-12-03). "Mummified Dinosaur May Have Outrun T Rex". Associated Press. http://www.redorbit.com/news/science/1166254/mummified_dinosaur_may_have_outrun_t_rex/index.html. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bell, P. R. (2012). Farke, Andrew A. ed. "Standardized Terminology and Potential Taxonomic Utility for Hadrosaurid Skin Impressions: A Case Study for Saurolophus from Canada and Mongolia". PLoS ONE 7 (2): e31295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031295. PMID 22319623.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Prieto-Márquez, A (2010). "Global phylogeny of Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) using parsimony and Bayesian methods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159 (2): 435–502. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00617.x.

- ↑ Weishampel, David B.; Horner, Jack R. (1990). "Hadrosauridae". in Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka. The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 534–561. ISBN 0-520-06727-4.

- ↑ Glut, Donald F. (1997). Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 69. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ↑ Prieto-Márquez, A.; Dalla Vecchia, F. M.; Gaete, R.; Galobart, À. (2013). "Diversity, relationships, and biogeography of the Lambeosaurine dinosaurs from the European archipelago, with description of the new aralosaurin Canardia garonnensis". PLoS ONE 8 (7): e69835. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069835. PMID 23922815.

- ↑ Prieto-Marquez, A.; Erickson, G.M.; Ebersole, J.A. (2016). "A primitive hadrosaurid from southeastern North America and the origin and early evolution of 'duck-billed' dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36 (2): e1054495. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1054495.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Boyle, Alan (2009-06-29). "How dinosaurs chewed". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 2009-07-02. https://web.archive.org/web/20090702125027/http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/archive/2009/06/29/1981788.aspx. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ Norman, David B.; Weishampel, David B. (1985). "Ornithopod Feeding Mechanisms: Their Bearing on the Evolution of Herbivory". American Naturalist 126 (2): 151–164. doi:10.1086/284406.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Williams, Vincent S.; Barrett, Paul M.; Purnell, Mark A. (2009). "Quantitative analysis of dental microwear in hadrosaurid dinosaurs, and the implications for hypotheses of jaw mechanics and feeding". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (27): 11194–11199. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812631106. PMID 19564603.

- ↑ "Hadrosaur Forelimb Study". Palaeo-electronica.org. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2009_3/180/discus.htm. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ↑ Bryner, Jeanna (2009-06-29). "Study hints at what and how dinosaurs ate". LiveScience. http://www.livescience.com/animals/090629-dino-teeth.html. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ Tweet, Justin S.; Chin, Karen; Braman, Dennis R.; Murphy, Nate L. (2008). "Probable gut contents within a specimen of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana". Palaios 23 (9): 624–635. doi:10.2110/palo.2007.p07-044r.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Lloyd, Robin (2008-09-25). "Plant-eating dinosaur spills his guts: Fossil suggests hadrosaur's last meal included lots of well-chewed leaves". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26893497/ns/technology_and_science-science/. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ This information comes from the aforementioned Alan Boyle source from June 29, 2009. However, this specific information is not included in the body of the article, but rather a response by Boyle to comments in the article. Since the comments were written by Boyle himself, and since they cite information he received specifically from Purnell, they are as legitimate a source of information as the article itself.

- ↑ Mallon, Jordan C.; Evans, David C.; Ryan, Michael J.; Anderson, Jason S. (2013). "Feeding height stratification among the herbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada". BMC Ecology 13: 14. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-13-14. PMID 23557203.

- ↑ Chin, K. (September 2007). "The Paleobiological Implications of Herbivorous Dinosaur Coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana: Why Eat Wood?". Palaios 22 (5): 554. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-087r. http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.2110%2Fpalo.2006.p06-087r. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Chin, Karen; Feldmann, Rodney M.; Tashman, Jessica N.. "Consumption of crustaceans by megaherbivorous dinosaurs: dietary flexibility and dinosaur life history strategies". Scientific Reports 7. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-11538-w.

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 Tanke, D.H. and Brett-Surman, M.K. 2001. Evidence of Hatchling and Nestling-Size Hadrosaurs (Reptilia:Ornithischia) from Dinosaur Provincial Park (Dinosaur Park Formation: Campanian), Alberta, Canada. pp. 206-218. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life—New Research Inspired by the Paleontology of Philip J. Currie. Edited by D.H. Tanke and K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press: Bloomington. xviii + 577 pp.

- ↑ Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science 332 (6030): 705–708. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820.

- ↑ Rothschild, B.M.; Tanke, D.H.; Helbling II, M.; Martin, L.D. (2003). "Epidemiologic study of tumors in dinosaurs". Naturwissenschaften 90 (11): 495–500. doi:10.1007/s00114-003-0473-9. PMID 14610645. http://www.springerlink.com/content/ktqqkxcqdc620keb/. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth (1998). "Evidence of predatory behavior by theropod dinosaurs". Gaia 15: 135–144. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. https://web.archive.org/web/20071117132451/http://vertpaleo.org/publications/jvp/15-576-591.cfm. Retrieved 2009-03-08. [not printed until 2000]

- ↑ Rothschild, Bruce; Tanke, Darren H. (2007). "Osteochondrosis is Late Cretaceous Hadrosauria". in Carpenter Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 171–183. ISBN 0-253-34817-X.

External links

- Timeline of hadrosaur research

- UCMP Tree of Life

- Trachodon

- "Mummified" Dinosaur Discovered In Montana, National Geographic 2002

Wikidata ☰ Q271841 entry