Biology:Magicicada cassinii

| Magicicada cassinii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female ovipositing | |

| File:Calling song of Magicicada cassini - pone.0000892.s002.oga | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Auchenorrhyncha |

| Family: | Cicadidae |

| Genus: | Magicicada |

| Species: | M. cassinii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Magicicada cassinii (Fisher, 1852)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cicada cassinii Fisher, 1852[2] | |

Magicicada cassinii,[lower-alpha 1] sometimes called the 17-year cicada, Cassin's periodical cicada or the dwarf periodical cicada,[9] is a species of periodical cicada. It is endemic to North America. It has a 17-year lifecycle but is otherwise indistinguishable from the 13-year periodical cicada Magicicada tredecassini. The two species are usually discussed together as "cassini periodical cicadas" or "cassini-type periodical cicadas." Unlike other periodical cicadas, cassini-type males may synchronize their courting behavior so that tens of thousands of males sing and fly in unison.[10][11] The species was first described by Margaretta Morris.[12] However, the specific name cassinii was in honour of John Cassin, an American ornithologist.

Description

The adult M. cassinii is very similar in appearance to other periodical cicadas. It is between 24 and 27 mm (0.94 and 1.06 in) long, measured from the front of the head to the tip of the wings folded over the abdomen. The head is black, the eyes are large and red, the pronotum is black apart from a narrow orange band at the edge of the sternites, and the abdomen is black. The legs are orange and the wings are translucent, with orange veins and dusky markings near the tips.[11]

Distribution and habitat

Magicicada cassinii is endemic to North America, its range extending across the northern belt of the United States and the southern part of Canada.[11]

Life cycle

These cicadas are true bugs and after having emerged from underground, the adults feed on sap sucked from trees and shrubs. Males amass in great numbers and sing in unison to attract females. The call lasts for two to four seconds and is a series of ticks followed by a drawn-out buzz which rises and falls in pitch. At the end of a chorus, males move to a new perch before starting the song again. After mating, the females insert their ovipositors into shoots and lay their eggs. These hatch about two months later and the first instar nymphs drop to the ground where they move underground and suck xylem sap from small rootlets. This sap is very low in nutritive value and the nymphs grow very slowly. They will moult five times, moving on to larger roots deep in the soil as they grow over a period of seventeen years. Finally, they all tunnel up through the soil and emerge into the open air, before climbing up the vegetation and shedding their skins for a final time to become adults. Although each population has a seventeen-year life cycle and emerges in synchrony, past environmental events have occasionally disrupted this pattern and there are several different broods in existence in various parts of the insect's range which emerge in different calendar years.[11][13] In fact, their life cycle can range from thirteen to twenty-one years.[14]

The different broods have been numbered, and the most recent emergence of Brood X occurred in Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia in May and June 2021.[13][9] Many broods have a sub-brood that emerge a few years before the regular brood. The Brood XIII sub-brood in the Chicago area emerged 4 years early in 2020.

Mating call Brood XIII sub-brood, Naperville, Illinois June 12, 2020

Male dorsal Brood XIII sub-brood, Naperville, Illinois June 13, 2020

Male ventral Brood XIII sub-brood, Naperville, Illinois June 13, 2020

Male crawling Brood XIII sub-brood, Naperville, Illinois June 13, 2020

Damage

In outbreak years, the cicadas do significant damage to the trees on which they lay eggs, especially saplings. The female cuts a slit in a twig in which to insert her eggs and this often causes the shoot to droop and defoliate. In larger twigs it may allow entry of disease organisms. The burden of feeding of the nymphs is also considerable. However, it has been shown that there is little long-term harm to mature trees.[15]

Alleged reward for blue eyed cicadas

A popular reoccurring urban legend purports to say that rare blue (or white) eyed cicadas will fetch rewards of up to one million dollars. According to the legend, biological laboratories, particularly at Vanderbilt University,[16] will pay a reward to any who catch such a specimen. And while it is true that blue eyed cicadas are extremely rare, occurring in only about one in every million insects, no laboratories currently offer any such reward.[17] However, Roy Troutman, an American entomologist and cicada researcher,[18] did in fact offer rewards for living blue eyed cicadas for cicada research in 2008. He is no longer offering rewards.[19]

Notes

- ↑ While the original and correct spelling for Fisher's 17-year species is cassinii,[2] with two 'i's, a large majority of publications have spelled the name cassini since the mid-1960s. However, the original spelling has been maintained throughout by taxonomic catalogues,[3][4][5][6] and the rules of nomenclature support the priority of cassinii (Article 33.4).[7] The correct spelling for the 13-year relative is tredecassini.[8]

References

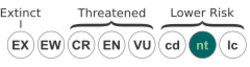

- ↑ World Conservation Monitoring Centre. (1996). Magicicada cassini. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 1996. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T12690A3373469.en.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fisher, J.C. (1852). "On a new species of Cicada". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 5: 272–275. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/26301507.

- ↑ Sanborn, A. F. (2013). Catalogue of the Cicadoidea (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha). With contributions to the bibliography by Martin H. Villet. Elsevier. Inc., Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- ↑ Duffels, J.P., and P. A. van der Laan. (1984). Catalogue of the Cicadoidea (Homoptera, Auchenorhyncha) 1956–1980. Series Entomologica vol. 34. Springer Netherlands. ISBN:978-90-6193-522-3

- ↑ Metcalf, Z.P., (1963). General Catalogue of the Homoptera. Fasc. 8. Cicadoidea. Part 1: Cicadidae. vii, Part 2. University of North Carolina State College, Raleigh, U.S.A.

- ↑ Dmitriev, D. (2003). 3I Interactive Keys and Taxonomic Databases.

- ↑ ICZN (1999). International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, 4th Edition . International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, Natural History Museum, London.

- ↑ Alexander, R.D., and T. E. Moore. (1962). The evolutionary relationships of 17-year and 13-year cicadas, and three new species (Homoptera, Cicadidae, Magicicada). Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology of the University of Michigan 121: 1–59.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Magicicada cassinii (Fisher, 1852) aka Cassini 17-Year Cicada". Cicada Mania. 14 April 2020. https://www.cicadamania.com/cicadas/magicicada-cassinii-fisher-1852-aka-cassini-17-year-cicada/. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ↑ "Periodical Cicada Page". University of Michigan. http://insects.ummz.lsa.umich.edu/fauna/Michigan_Cicadas/Periodical/. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer. p. 2792. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=i9ITMiiohVQC.

- ↑ McNeur, Catherine. "The Woman Who Solved a Cicada Mystery—but Got No Recognition" (in en). https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-woman-who-solved-a-cicada-mystery-but-got-no-recognition/.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Post, Susan L. (2004). "A Trill of a Lifetime". The Illinois Steward. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070510060933/http://www.inhs.uiuc.edu/highlights/periodicalCicada.html. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ Campbell, Matthew (18 August 2015). "Genome expansion via lineage splitting and genome reduction in the cicada endosymbiont Hodgkinia - Supporting Information". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (33): 10192–10199. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421386112. PMID 26286984. PMC 4547289. https://www.pnas.org/content/suppl/2015/05/16/1421386112.DCSupplemental/pnas.201421386SI.pdf. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ↑ Cook, William M.; Holt, Robert D. (2002). "Periodical cicada (Magicicada cassini) oviposition damage: visually impressive yet dynamically irrelevant". American Midland Naturalist 147 (2): 214–224. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2002)147[0214:PCMCOD2.0.CO;2]. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110807172257/http://people.biology.ufl.edu/rdholt/holtpublications/119.pdf.

- ↑ "Bad buzz about blue-eyed cicadas". 2 June 2011. https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2011/06/02/bad-buzz-about-blue-eyed-cicadas.

- ↑ "'Cicada cash' rumor squashed". https://www.baltimoresun.com/bal-md.cicadas18may18-story.html.

- ↑ Cooley, John R.; Arguedas, Nidia; Bonaros, Elias; Bunker, Gerry; Chiswell, Stephen M.; Degiovine, Annette; Edwards, Marten; Hassanieh, Diane et al. (2018). "The periodical cicada four-year acceleration hypothesis revisited and the polyphyletic nature of Brood V, including an updated crowd-source enhanced map (Hemiptera: Cicadidae: Magicicada)". PeerJ 6: e5282. doi:10.7717/peerj.5282. PMID 30083444. PMC 6074776. https://peerj.com/articles/5282/.

- ↑ "Did Someone Offer a Reward for White or Blue-eyed Cicadas?". 5 July 2015. https://www.cicadamania.com/cicadas/did-someone-offer-a-reward-for-white-or-blue-eyed-cicadas/.

Wikidata ☰ Q234354 entry