Biology:Nasutoceratops

| Nasutoceratops | |

|---|---|

| |

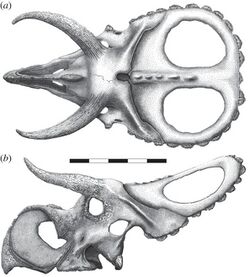

| Reconstructed skull at the Arizona Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Centrosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Nasutoceratopsini |

| Genus: | †Nasutoceratops Sampson et al., 2013 |

| Type species | |

| †Nasutoceratops titusi Sampson et al., 2013

| |

Nasutoceratops is an extinct genus of ceratopsian dinosaur. It is a basal centrosaurine which lived during the Late Cretaceous Period (late Campanian, about 76.0-75.5 Ma). Fossils have been found in southern Utah, United States. Nasutoceratops was a large, ground-dwelling, quadrupedal herbivore with a short snout and unique rounded horns above its eyes that have been likened to those of modern cattle. Extending almost to the tip of its snout, these horns are the longest of all the members of the centrosaurine subfamily. The presence of pneumatic elements in the nasal bones of Nasutoceratops are a unique trait and are unknown in any other ceratopsid.

The holotype skull is approximately 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in length. Its body length has been estimated at 4.5 metres (14.8 ft), its weight at 1.5 tonnes (1.7 short tons). The part of the snout around the nostril is strongly developed, representing about three quarters of the skull length in front of the eye sockets. The contact surface between the maxilla and the praemaxilla is exceptionally large. The maxilla also has a large internal flange contacting the praemaxilla via two horizontal facets. The skull frill is more or less circular with its widest point at the middle edge. The osteoderms on the frill edge, the epiparietals and episquamosals, do not have the form of spikes but are shaped like simple low crescents. The rear frill edge is not notched but instead has an epiparietal on the midline.

Discovery and naming

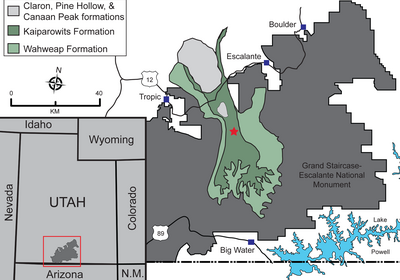

Since 2000, the Natural History Museum of Utah (UMNH) and the Bureau of Land Management have been conducting paleontological surveys of the Kaiparowits Formation at the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument (GSENM) in southern Utah. This national monument was established in 1996 in part for the preservation and study of its fossils, and the surveys there have yielded a wide array of unique dinosaur fossils. Field crews from other institutions have also participated, and the collaborative effort has been called the Kaiparowits Basin Project.[1][2] Among the discoveries made were three new ceratopsian (horned dinosaur) taxa, one of which was identified from UMNH Locality VP 940 discovered by the then graduate student and technician Eric K. Lund during the 2006 field season.[2][3]

Prior to this project, the only ceratopsian remains found at the formation were uninformative, isolated teeth, and centrosaurines were almost exclusively known from western North America.[4][5] Excavated fossils were transported to the UMNH, where the blocks were prepared by volunteers with pneumatic air scribes and needles and subsequently reassembled; it took a few years for the team to assemble the skull of this dinosaur.[1][6][7] It was preliminarily referred to as "Kaiparowits new taxon C" and identified as a centrosaurine (the first member of this ceratopsid group known from the formation) in 2010, and as "Kaiparowits centrosaurine A" in 2013. Three specimens of this taxon were collected; UMNH VP 16800 in 2006, with UMNH VP 19469 and UMNH VP 19466 collected in subsequent years.[2][3][8]

The paleontologists Scott D. Sampson, Lund, Mark A. Loewen, Andrew A. Farke and Katherine E. Clayton briefly described and scientifically named the new genus and species Nasutoceratops titusi in 2013, with specimen UMNH VP 16800 as the holotype (on which the scientific name is based). The generic name is derived from the Latin word nasutus meaning "large-nosed", and ceratops, which means "horned-face" in Latinized Greek. The specific name titusi is an eponym that honors the paleotologist Alan L. Titus for his important efforts in recovering fossils from the GSENM.[5][4] Lund had informally used the spelling Nasutuceratops for this dinosaur in his 2010 thesis wherein he also described it.[9] In 2016, Lund, Sampson, and Loewen published a more detailed description of the preserved fossil material.[4]

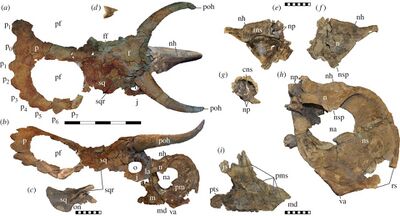

The holotype specimen UMNH VP 16800 consists of a partial, associated, and nearly complete skull of a subadult (interpreted as such based on fusion of skull elements and bone surface texture) that preserves most of the skull roof, which was collected with an articulated and almost complete left forelimb, an associated yet very fragmentary right hindlimb, much of the pectoral girdle, an almost complete syncervical vertebra, and three associated but fragmentary dorsal vertebrae, as well as three patches of skin impressions associated with the left forelimb (the only ceratopsid skin impressions known from the GSENM and some of the few known worldwide). Two specimens from other quarries were assigned due to shared features with the holotype: specimen UMNH VP 19466, a disarticulated adult skull consisting of the partial right and left premaxillae, a right maxilla and right nasal, and specimen UMNH VP 19469, an isolated squamosal bone of a subadult. Taken together, these specimens represent about 80% of the skull and about 10% of the postcranial skeleton.[5][4]

In the UMNH press release accompanying the description of Nasutuceratops, the large nose of the dinosaur was emphasized, with Sampson calling it a "jumbo-sized schnoz".[8] This was reflected by news outlets, with one article titled "paleontologists discover, mock, new dinosaur species", and another including humorous poems about the dinosaur by columnist Alexandra Petri, such as: "Higgledy piggledy, Nasutoceratops, Long-nosed horned just-unearthed dino du jour, Probably used its horns, For showing dominance, During its courtship (although we’re not sure)".[10][11][12][13][7] Nasutuceratops was featured in the 2019 Jurassic World short film Battle at Big Rock and the 2022 film Jurassic World Dominion, in what an UMNH article called a "pivotal role".[14][15] Colin Trevorrow, the director of the former, called Nasutuceratops "a beautiful herbivore that feels like a Texas Longhorn".[16]

Description

Nasutoceratops is estimated to have been 4.5 m (14.8 ft) long and to have weighed 1.5 t (1.7 short tons).[17] The subadult holotype skull is approximately 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length.[4] As a centrosaurine ceratopsid, it would have been a large bodied, quadrupedal dinosaur with a huge skull, a hooked upper beak, a heavily constructed skeleton, a shortened, down-swept tail, a large pelvis indicating powerful muscles, and short digits.[17]

Skull

The front part of the skull of Nasutoceratops is unusually deep from top to bottom, especially around the nostril area, similar to that of Diabloceratops. The external nostril forms 75% of the skull length in front of the eye sockets, which is unique for this genus. The snout region is almost circular overall, which is typical of centrosaurines, but it differs from more derived centrosaurines and is more similar to Diabloceratops in that expands upwards, giving the snout-region a bulbous appearance. The rostral bone (feature unique to ceratopsians, which forms the upper beak and contacts the front part of the premaxilla) is not preserved in Nasutoceratops, but by inferring from the contact area of the premaxilla, it has been interpreted as triangular in side view, similar to centrosaurines and unlike chasmosaurines (the other main group of ceratopsids). While the premaxilla tends to be similar in other centrosaurines, and that of Nasutoceratops shares features such as having a well-developed septum, a thick, downward projecting angle, is toothless, and thin and blade-like, it can be distinguished in several features. The premaxilla differs in being very tall, with a slight protuberance on the upper edge in front of the nasal bone like in Diabloceratops, and in these two dinosaurs, the upper extend of the premaxilla is higher than the front part of the nasal. The deep, thin, and rounded premaxillary septum at the front of the premaxilla appears to be more extensive than in any other ceratopsid, probably due to the general upwards expansion of the snout region. Unlike in other centrosaurines, this septum extends hindwards to underlie the horn-core of the nasal. The premaxilla has an unusual hindwards projecting process that ascends upwards more than in any other ceratopsid, which approaches the upper margin of the skull. This is similar to the condition in basal (early diverging) neoceratopsians like Protoceratops. A short hard palate is present on the premaxilla, a feature otherwise only seen in Pachyrhinosaurus among censtrosaurines.[4]

The maxilla of Nasutoceratops was roughly triangular, and when seen front the side was divided into two rami (portions of bone); a dorsal ascending ramus and a ventral horizontal ramus, the latter which contained the upper tooth row. The dorsal ascending ramus had a thin-walled contact surface for the hindwards projecting process of the maxilla, and the condition of this enlarged, steep ramus is unique for this dinosaur. The contact surface of the maxilla for the premaxilla is very expanded (forming a contact shelf), and has a deeply excavated sulcus, unlike in other ceratopsids. Each maxilla is estimated to have contained 29 teeth, but it has not been determined whether they were double-rooted like in other ceratopsids or single-rooted like in neoceratopsians. The maxillary teeth have nearly vertical wear facets on their inwards surfaces, as is typical of ceratopids. The maxilla is distinct from most ceratopsids in that the tooth-row is displaced outwards to the side in relation to the front of the maxilla, which is similar to Diabloceratops and Avaceratops, as well as more basal neoceratopsians. A maxillary flange at the front which contributed to the hard palate by slotting into the premaxilla was double-socketed, a unique feature of Nasutoceratops. The back of the maxilla has a somewhat well-developed buccal excavation on the side towards the "cheek", which seems to be less defined than in other ceratopsids.[4]

The nasal bones of Nasutoceratops form the upper part of the front end of the skull, which is relatively short from front to back compared to more derived centrosaurines, at 248 mm (9.8 in). That the part of the skull in front of the eyes was very short is a result of the abbreviated basal and maxilla, and it may be the shortest of any centrosaurine. The nasal horn-core above the nasal opening is low, long, and blade-like, pinched from side to side along the hind part, and with a somewhat raised teardrop shaped expansion at the front which is partially formed by the premaxilla. The surface texture of this horn-core appears to be rugose, as is typical for ceratopsids. The nasals flare out to the sides in front of the horn-core, which forms a "roof" in front of much of the nasal cavity, which is also seen in some other centrosaurines, but not in more derived members. There is a narial spine formed by the nasal and premaxilla, as typical in centrosaurines, which is deflected into the nasal cavity, which results in an hour-glass shaped when the cavity is viewed from the front. Seen from the side, the inner nasal opening is relatively small and slightly crescent-shaped, with an upwards arched front border. The longest axis of the internal nostril opening is 160 mm (6.3 in) long and almost horizontally oriented, whereas it is almost vertical in most other centrosaurines. The nasal bones had well-developed internal cavities behind the horn-core, which suggests there were hollow, and possibly pneumatized; pneumatic nasals are unknown in other ceratopsians.[4]

The supraorbital horn-cores (brow horns) above and in front of the eye sockets is one of the most notable features of Nasutoceratops. The supaorbital horn-cores of ceratopsids are outgrowths of the postorbital bone, with slight contribution from the palpebral bone, but those of Nasutoceratops differ from all ceratopsids in orientation and (to a lesser degree) shape. The horn-cores are stongly curved; their bases are pointed forwards and outwards, then curve inwards, and ultimately twist their points upwards. The horns are very elongated and span approximately 40% of total skull length, almost reaching the level of the snout tip. This horn configuration has been described as superficially similar to that of a Texas Longhorn bull or to a cow. With a bone core length of up to 457 mm (18.0 in), the brow horns of Nasutoceratops are the longest known of any centrosaurine, both in absolute and relative terms. The majority of other centrosaurines have relatively short brow horns, with elongated horns only being present in basal forms like Diabloceratops, Avaceratops, and Albertaceratops. The brow horns of Nasutoceratops are very different from those of other ceratopsids, where they point mainly up and away from the eyes, without torsion.[4][5][18]

The postorbital bone forms most of the upper skull roof, and most of the upper margin of the orbit or eye socket, which was epilliptical, as is typical for ceratopsids. The skull roof was very vaulted around the eye region, which gives the impression that Nasutoceratops had a forward facing "forehead" across its width, similar to Diabloceratops and Albertaceratops, as well as many chasmosaurines. The epijugal bone (or cheek horn) is roughly trihedral in shape and is 85 mm (3.3 in) long and 78 mm (3.1 in) wide at the base, the largest known among centrosaurines. It is similar to that of Diabloceratops in being relatively large and having a flattened front surface, but large epijugal mainly typical for chasmosaurines, and may be a basal feature among ceratopsids. As is general for ceratopsian epiossifications (the accessory ossifications that formed the horns and lined the margins of the neck frills in ceratopsids), the external texture is very vascularized and rugose, and it was most likely covered by a keratinous sheath when the dinosaur was alive.[4]

The parietosquamosal frill at the back of the skull was formed by the fused parietal bones and paired squamosal bones, as in all other ceratopsids. The frill is almost circular with its widest point at the middle region. The total length of the frill is around 610 mm (24 in), almost equal to the length of the basal skull (from premaxilla to occipital condyle, excluding the frill), with a width around 800 mm (31 in). While the frill is similar to those of Centrosaurus, Achelousaurus, and Einiosaurus in overall shape, it greatly differs from them in the organization of the episquamosals and epiparietals. The frill has two large, oval parietal fenestrae, one on each parietal, as is typical for centrosaurines. The longest axis of each fenestra (from front to back) is about 350 mm (14 in) long, comprising about 57% of the frills length, and the width from side to side is 260 mm (10 in), comprising about 33% of the frill's width. The frill is saddle-shaped, with the upper surface being convex across from side to side and concave from front to back, as typical for centrosaurines. The squamosal bone is similar to those of other centrosaurines, and forms about a third of the frill. The squamosal has a high ridge on its upper surface, running from the direction of the eye socket towards the squamosal rim, which is unusual for centrosaurines. The presence of four or five undulations on the margin of the squamosal suggests that episquamosals were attached to these, and their shape was probably similar to the epiparietals on the rest of the frill, which are relatively uniform.[4][5]

The fused parietal bones form about two thirds of the frill, and unlike the squamosal which is usually conservative across centrosaurines, the parietal is mostly unique to a species and the most diagnostic part for determining interrelationships. The parietal on one side has seven undulations on the margin as well as an undulation on the midline, all except one of which were capped by an epiparietal. Midline epiparietals are otherwise only known in chasmosaurines, and another contrast with other centrosaurines is that the frill is rounded at the back of the midline, with no indentation there. The median bar between the fenestrae is thin from top to bottom near the margins but thick at the midline, and is straplike overall. The upper side of the median bar is convex at the front, and forms a low, rounded ridge with five undulations of varying height at the midline. The median bar widens toward the top f the frill, where it widens into the also broad and straplike transverse parietal bar. The forwards projected ramus on the side of the parietal rounded out the frill and enclosed the fenestrae; the ramus is thickest near the side edges where the marginal undulations and epiparietals are located, and thinnest towards the fenestrae. The parital differs from that of most centrosaurines except Avaceratops in lacking a distinct indentation at the midline, in having an epiparietal at the midline, and in lacking the well-developed hooks and spikes that are typical for the group. Since the holotype was not fully grown, it is possible such hooks would have developed as it matured, but this is considered unlikely due to the fusion of its epiparietals on the frill and fusion of other bones related to maturity. The epiparietals are low, roughly crescent-shaped, asymmetrical and wedge-shaped, and their lower surface is slightly concave. They project outward on the same plane as the underlying part of the parietal, with some downwards flexion. They are of almost the same size along the hind and side margins of the frill, but are slightly smaller towards the front.[4]

Postcranial skeleton and skin impressions

Ceratopsids are mainly distinguished through features pertaining to their skull roofs, and the postctranial skeleton of Nasutoceratops is typical of the group. Typical of ceratopsids, the three frontmost neck vertebrae were fused into a syncervical vertebra, and that of Nasutoceratops is particularly similar to that of Styracosaurus. At the front, it had the characteristic deep cotyla for articulation with the occipital condyle at the back if the skull. The dorsal vertebrae are also typical for ceratopsids, with their centrae being shorte from front to back and their neural arches being very tall. The articular facets of the centra are almost circular to pear-shaped, similar to those of Styracosaurus. The transverse processes at the sides of these vertebrae are elevated and have prominent zygapophyses, typical for the group.[4]

The scapula is long and relatively slender, its hind part is flattened and flared, and is similar to those of other centrosaurines overall. The coracoid is fused to the front end of the scapula, as is often the case in ceratopsids, and there is a large foramen at the front. The humerus is 475 mm (18.7 in) long, and has a hemispheric humeral had and prominent delopectoral crest, and consists of almost half the whole length of the humerus, typical of ceratopsids. The humerus is long and slender, but otherwise typical for ceratopsids. The ulna is 400 mm (16 in) long and has a large olecranon process where the triceps inserted, typical of ceratopsids. The radius is thin with expanded ends, as is typical of ceratopsids.[4]

The three patches with skin impressions associated with the scapula and humerus of the left forelimb of Nasutoceratops specimen UMNH VP 16800 are preserved both as casts and molds, and show three kinds of tubercle patterns. The patches are identified as patch A, B, and C, and cover 120 cm2 (19 sq in), 84 cm2 (13.0 sq in), and 25 cm2 (3.9 sq in), respectively. Patch A consists of tightly packed, oval to almost circular tubercles which vary from 2–8 mm (0.079–0.315 in) in diameter, and are arranged in irregular rows. Patch B consists of larger, loosely packed almost circular tubercles, varying from 5–11 mm (0.20–0.43 in) in diameter, also arranged in irregular rows. Patch C is the most notable impression, which consists of raised hexagonal tubercles that measure 8–11 mm (0.31–0.43 in) in diameter, and are surrounded by triangular grooves. This patch is located between patch A and B.[4]

Patches A and B are similar to integument impressions known from other ceratopsians (including Psittacosaurus, Chasmosaurus, and Centrosaurus) which have pavement tubercles that are variably sized, round to epileptical, arranged in similarly irregular rows. Patch C differs in consisting of hexagonal tubercles that are relatively equal in size, which are delineated by the surrounding tubercles by triangular creases and patterns that are unusual among ceratopsians. Similar hexagram-like structures were later observed on the limbs of Psittacosaurus, and have been called "stars". There is also no evidence in Nasutoceratops of round, ossicle-like scales surrounded by pavement tubercles, as seen in Chasmosaurus and Centrosaurus.[4][19]

Classification

Nasutoceratops was assigned to Centrosaurinae by Sampson and colleagues in 2013 based on features such as the premaxilla having a pronounced downwards angle, the almost circular narial region, having a narial spine composed on the nasal and premaxilla, and in having an abbreviated squamosal with a stepped hind margin. But despite its late Campanian age, and being contemporary with the derived northern centrosaurines Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus, Nasutoceratops retained more "primitive" features, such as the maxillary tooth row being to the side, elongated supraorbital horncores, and pronounced epijugals, which are absent in other centrosaurines of the time. The phylogenetic analysis of the study found Nasutoceratops to be the sister taxon of Avaceratops from the Judith River Formation of Montana, the two forming a clase neaer the base of Centrosaurinae.[5]

In 2016, this clade was named Nasutoceratopsini; it contains Nasutoceratops as well as ANSP 15800 (the holotype of Avaceratops), MOR 692 (previously treated as an adult specimen of Avaceratops), the newly described CMN 8804 from the Oldman Formation, and another undescribed ceratopsian found in Malta, Montana.[20][21][22]

The cladogram below follows the 2023 phylogenetic analysis by Hiroki Ishikawa and colleagues, and shows the position of Nasutoceratops within Ceratopsidae:[23]

| Ceratopsidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiogeography

Though the area of Laramidia was only 20 percent that of modern North America, it saw a major evolutionary radiation of dinosaurs, including the common hadrosaurs and ceratopsians. It has been postulated that there was a latitudinal array of dinosaur "provinces" or biomes on Laramidia during the Campanian and Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous, the boundary lying around modern northern Utah and Colorado; the same major clades are known from the north and south but are distinct from each other at the genus and species levels. This hypothesis has been challenged; one argument claims that northern and southern dinosaur assemblages during this time were not coeval but reflect a taxonomic distribution over time, which gives the illusion of geographically isolated provinces, and that the distinct assemblages may be an artifact of sampling bias between geological formations. Due to a lack of well-dated fossils from southern Laramidia, this idea had been difficult to test, but discoveries in the Kaiparowits Formation have increased knowledge of fossil vertebrates from the region during the Late Cretaceous. The evolutionary radiation of ceratopsids appears to have been restricted both in time and geographically (the turnover of species was high, and each existed for less than a million years), most taxa being known from latest Cretaceous sediments in the Western Interior Basin, therefore appearing to have originated and diversified on Laramidia.[1][24]

According to the 2013 study, the existence of Nasutoceratops would support the hypothesis of faunal separation between the north and south of Laramidia. Its clade would differ from the northern centrosaurines in the retention of long brow horns and a short nose horn, combined with developing, convergent with the Chasmosaurinae, low epiparietals.[5]

Paleobiology

In 2016, Lund and colleagues stated that the functional adaptations associated with the distinct cranial features of Nasutoceratops are unknown. They suggested that the very short and deep front part of the skull in front of the eyes may have been connected to a change toward more derived masticatory functions in basal ceratopsians. This morphology increased the mechanical advantage during mastication by moving the beak closer to the joint of the lower jaw. The narial region of Nasutoceratops is deep mainly due to the premaxilla and maxilla having steeply rising, enlarged contact surfaces, but the function of this is unknown. because the contact surfaces are steeply inclined and more robust than those o more derived relatives, this feature may be connected with absorbing larger bite forces. The pneumaticity in the nasal may have derived from a source in front of the nasal. Pneumaticity in this region has been associated with a variety of functions in vertebrates such as moisture exchange, shock absorption, vocal resonance, and weight reduction, but the function in Nasutoceratops is unclear.[4] Sampson stated in a 2013 press release that the large snout probably did not have anything to do with a heightened sense of smell, since olfactory sensors are located further back in the head, closer to the brain.[8]

In a 2017 Master's thesis, paleontologist Nicole Marie Ridgwell described two coprolites (fossilized dung) from the Kaiparowits Formation which, due to their size, may have been produced by a member of one of three herbivorous dinosaur groups known from the formation: ceratopsians (including Nasutoceratops), hadrosaurs, or ankylosaurs (rarest of the three groups). The coprolites contained fragments of angiosperm wood (which indicates a diet of woody browse); though there was previously little evidence of dinosaurs consuming angiosperms, these coprolites showed that dinosaurs adapted to feeding on them (they only became common in the Early Cretaceous, diversifying in the Late Cretaceous). The coprolites also contained traces of mollusc shell, arthropod cuticle, and lizard bone that may have been ingested along with the plant material. They were found near other herbivore coprolites that contained conifer wood. Ridgwell pointed out that the dental anatomies of ceratopsians and hadrosaurs (with dental batteries comprising continuously replaced teeth) were adapted to process large quantities of fibrous plants. The different diets represented by the coprolites may indicate niche partitioning among the herbivores of the Kaiparowits Formation ecosystem, or that there was seasonal variation in diet.[25]

Function of skull ornamentation

Sampson and colleagues stated in 2013 that while various hypotheses about the function of ceratopsid ornamentation have been proposed, the consensus at the time was use in intraspecific signalling and intraspecific combat, with the debate focusing on either species recognition (driven by natural selection) or mate competition (driven by sexual selection). Other ideas have ranged from protection against predators and thermoregulation. They pointed out that either way, the evolutionary changes in the two centrosaurine clades were concentrated in different parts of the skull, with the clade that included Avaceratops and Nasutoceratops reducing frill ornamentation but elaborating the supraorbital horns, and the clade that indluded Spinops and Pachyrhinosaurus clade reducing supraorbital horns but hypertrophying nasal horn and frill orientation, which distributed their distinct signalling structures all across the skull roof.[9][8] Loewen stated in the 2013 press release that the horns were probably used as visual signs of dominance, and as weapons against rivals when that was not enough.[8]

In 2016, Lund and colleagues suggested that if the mate competition hypothesis applied to the very long and robust supraorbital horns of Nasutoceratops, their orientation towards the front and sides and torsional twist may have enabled interlocking of horns with opponents of the same species, as seen in many modern bovids. They noted that the paleontologist Andrew A. Farke had earlier studied the function of ceratopsid supraorbital horns by using scale models, and found three plausible horn locking positions for Triceratops that could also apply to Nasutoceratops; "single horn contact", "full horn locking", and "oblique horn locking". Pathologies in the skulls of Triceratops and Centrosaurus, with those in the former concluded to be consistent with trauma resulting from antagonistic behaviour, but those of the latter not as conclusive, and Lund and colleagues found that such hypothesis could not be ruled out for Nasutoceratops.[4] The paleontologist Gregory S. Paul suggested in 2015 that the forwards directed horns of Nasutoceratops indicated a frontal thrusting action.[17]

Paleoenvironment

Nasutoceratops is known from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, which dates to the late Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous epoch, and stratigraphically occurs in the formation's middle unit (which ranges 200–350 m (656.2–1,148.3 ft)), in sediments dating to 75.51-75.97 Ma million years ago. The formation was deposited in the southern part of a basin (the Western Interior Basin) on the eastern margin of a landmass known as Laramidia (an island continent consisting of what is now western North America) within 100 km (62 mi) of the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea in the center of North America that divided the continent (the eastern landmass is known as Appalachia).[4][26][27] The basin was broad, flat, crescent-shaped, and bounded by mountains on all sides except the Western Interior Seaway at the east.[28] The formation represents an alluvial to coastal plain setting that was wet, humid, and dominated by large, deep channels with stable banks and perennial wetland swamps, ponds, and lakes. Rivers flowed generally west across the plains and drained into the Western Interior Seaway; the Gulf Coast region of the United States has been proposed as a good modern analogue (such as the current day swamplands of Louisiana). The formation preserves a diverse and abundant range of fossils, including continental and aquatic animals, plants, and palynomorphs (organic microfossils).[29][6]

Other ornithischian dinosaurs from the Kaiparowits Formation include ceratopsians such as the chasmosaurines Utahceratops and Kosmoceratops (and possibly a second yet unnamed centrosaurine), indeterminate pachycephalosaurs, the ankylosaurid Akainacephalus, an indeterminate nodosaurid, the hadrosaurs Gryposaurus and Parasaurolophus, and an indeterminate, basal neornithischian. Theropods include the tyrannosaurid Teratophoneus, the oviraptorosaur Hagryphus, an unnamed ornithomimid, the troodontid Talos, indeterminate dromaeosaurids, and the bird Avisaurus. Other vertebrates include crocodiles (such as Deinosuchus and Brachychampsa), turtles (such as Adocus and Basilemys), pterosaurs, lizards, snakes, amphibians, mammals, and fishes.[28][30][31] The two most common groups of large vertebrates in the formation are hadrosaurs and ceratopsians (the latter representing about 14 percent of associated vertebrate fossils), which may either indicate their abundance in the Kaiparowits fauna or reflect preservation bias (a type of sampling bias) due to these groups also having the most robust skeletal elements.[3] Eggs from dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles have also been found.[32] The swamps and wetlands were dominated by up to 30 m (98 ft) cypress trees, ferns, and aquatic plants including giant duckweed, water lettuce, and other floating angiosperms. Better-drained areas were dominated by forests of up to 10–20 m (33–66 ft) dicot trees and occasional palms, with an understory including ferns. Well-drained areas further away from wet areas were dominated by conifers up to 30 m (98 ft), with an understory comprising cycads, small dicot trees or bushes, and possibly ferns.[28]

In 2010, the paleontologist Michael A. Getty and colleagues examined the taphonomy (changes occurring during decay and fossilization) of the holotype specimen and the sedimentological circumstances under which it was preserved. The more or less articulated holotype specimen was found in a sandstone channel lithofacies (the rock record of a sedimentary environment), and may have been much more complete when it was deposited. While the skull and forelimb were articulated and in close association, most of the postcranial skeleton was disarticulated and displaced before being deposited, which is indicated by the random distribution of those bones around the skull. The sandstone that entombed the forelimb preserved patches of skin, which is very rare for ceratopsians, and it seems plausible that the carcass was partially articulated with flesh and skin when it was washed into a stream bed. The winnowing and displacement of most of the skeleton, which left just the skull and forelimb in articulation at the time of burial, would have resulted from some rotting and disarticulation in the river channel. The missing parts of the skull were eroded and lost.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Sampson, S. D.; Loewen, M. A.; Farke, A. A.; Roberts, E. M.; Forster, C. A.; Smith, J. A.; Titus, A. L.; Stepanova, A. (2010). "New horned dinosaurs from Utah provide evidence for intracontinental dinosaur endemism". PLOS ONE 5 (9): e12292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012292. PMID 20877459. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...512292S.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Loewen, M.; Farke, A. A.; Sampson, S. D.; Getty, M. A.; Lund, E. K.; O’Connor, P. M. (2013). "Ceratopsid dinosaurs from the Grand Staircase of Southern Utah". At the Top of the Grand Staircase: The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 488–503. ISBN 978-0-253-00883-1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Getty, M. A.; Loewen, M. A.; Roberts, E.; Titus, A. L.; Sampson, S. D. (2010), "Taphonomy of horned dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase – Escalante National Monument, Utah", in Ryan, M. J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J.; Eberth, D. A., New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 478–494, ISBN 978-0253353580

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 Lund, Eric K.; Sampson, Scott D.; Loewen, Mark A. (2016). "Nasutoceratops titusi (Ornithischia, Ceratopsidae), a basal centrosaurine ceratopsid from the Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36 (2): e1054936. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1054936.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Sampson, S. D.; Lund, E. K.; Loewen, M. A.; Farke, A. A.; Clayton, K. E. (2013). "A remarkable short-snouted horned dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous (late Campanian) of southern Laramidia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280 (1766): 20131186. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1186. PMID 23864598.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sampson, S. D. (2012). "Dinosaurs of the lost continent". Scientific American 306 (3): 40–47. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0312-40. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 22375321. Bibcode: 2012SciAm.306c..40S.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Dinosaur gets named for his really big nose". The Denver Post. 2013. https://www.denverpost.com/2013/07/17/dinosaur-gets-named-for-his-really-big-nose/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Carpenter, Patti (8 October 2013). "Big-Nosed, Long-Horned Dinosaur Discovered in Utah". Natural History Museum of Utah. https://web.archive.org/web/20131008131645/http://newsdesk.nhmu.utah.edu/newsdesk/releases/big-nosed-long-horned-dinosaur-discovered-utah.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Eric Karl Lund (2010). Nasutuceratops titusi, a new basal centrosaurine dinosaur (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the upper cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation, Southern Utah. Department of Geology and Geophysics University of Utah (Thesis). pp. 172 pp. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- ↑ Ohlheiser, Abby (18 July 2013). "Paleontologists Discover, Mock, New Dinosaur Species" (in en). The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/paleontologists-discover-mock-newly-discovered-dinosaur/313183/.

- ↑ Petri, Alexandra (2 December 2021). "Three-horned poems for the new dinosaur, Nasutoceratops, relative of the triceratops". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/compost/wp/2013/07/17/three-horned-poems-for-the-new-dinosaur-nasutoceratops-relative-of-the-triceratops/.

- ↑ Memmott, Mark (2013). "Newly Discovered Dinosaur Sure Had One 'Supersize Schnoz'". NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2013/07/17/203014694/newly-discovered-dinosaur-sure-had-one-supersize-schnoz.

- ↑ Dell'Amore, Christine (4 November 2013). "New Big-Nosed Horned Dinosaur Found in Utah". National Geographic News. https://web.archive.org/web/20131104015103/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/07/130717-new-dinosaur-utah-nasutoceratops-paleontology-animals-science/.

- ↑ Whalen, Andrew (16 September 2019). "All 7 Dinosaurs in 'Battle at Big Rock,' Including Nasutoceratops". Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/dinosaurs-battle-big-rock-jurassic-world-short-film-nasutoceratops-1459474.

- ↑ Irmis, Randall (21 June 2022). "NHMU Dinosaur Stars in Jurassic World Dominion". nhmu.utah.edu. https://nhmu.utah.edu/articles/2023/05/nhmu-dinosaur-stars-jurassic-world-dominion.

- ↑ Russell, Steve (12 September 2019). "Jurassic World's Short Film Will Introduce Two New Dinosaurs". CBR. https://www.cbr.com/jurassic-world-short-film-new-dinosaurs/.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Paul, G. S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2 ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 285-287. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- ↑ Hone, Dave (2013-07-17). "Newly discovered dinosaur Nasutoceratops had cow-like horns". guardian.co.uk. London, UK: Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/lost-worlds/2013/jul/17/dinosaur-nasutoceratops-cow-horns.

- ↑ Bell, Phil R.; Hendrickx, Christophe; Pittman, Michael; Kaye, Thomas G.; Mayr, Gerald (2022). "The exquisitely preserved integument of Psittacosaurus and the scaly skin of ceratopsian dinosaurs". Communications Biology 5 (1). doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03749-3.

- ↑ Ryan, M.J.; Holmes, R.; Mallon, J.; Loewen, M.; Evans, D.C. (2017). "A basal ceratopsid (Centrosaurinae: Nasutoceratopsini) from the Oldman Formation (Campanian) of Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 54 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1139/cjes-2016-0110. Bibcode: 2017CaJES..54....1R.

- ↑ Lund, Eric K.; O’Connor, Patrick M.; Loewen, Mark A.; Jinnah, Zubair A. (2016). "A new centrosaurine ceratopsid, Machairoceratops cronusi gen et sp. nov., from the Upper Sand Member of the Wahweap Formation (Middle Campanian), Southern Utah". PLOS ONE 11 (5): e0154403. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154403. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1154403L.

- ↑ Rivera-Sylva, Héctor E.; Hedrick, Brandon P.; Dodson, Peter (2016). "A Centrosaurine (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) from the Aguja Formation (Late Campanian) of Northern Coahuila, Mexico". PLOS ONE 11 (4): e0150529. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150529. PMID 27073969. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1150529R.

- ↑ Ishikawa, Hiroki; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Manabe, Makoto (2023). "Furcatoceratops elucidans, a new centrosaurine (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the upper Campanian Judith River Formation, Montana, USA". Cretaceous Research 151: 105660. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105660.

- ↑ Sampson, S. D.; Loewen, M. A. (2010), "Unraveling a radiation: a review of the diversity, stratigraphic distribution, biogeography, and evolution of horned dinosaurs. (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae)", in Ryan, M. J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J.; Eberth, D. A., New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 405–427, ISBN 978-0253353580

- ↑ Ridgwell, N. M. (2017). Description of Kaiparowits coprolites that provide rare direct evidence of angiosperm consumption by dinosaurs. Museum and Field Studies Graduate Theses & Dissertations (Thesis). Archived from the original on June 30, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ↑ Roberts, E. M.; Deino, A. L.; Chan, M. A. (2005). "40Ar/39Ar age of the Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, and correlation of contemporaneous Campanian strata and vertebrate faunas along the margin of the Western Interior Basin". Cretaceous Research 26 (2): 307–318. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.01.002. Bibcode: 2005CrRes..26..307R.

- ↑ Fowler, D. W.; Wong, William O. (2017). "Revised geochronology, correlation, and dinosaur stratigraphic ranges of the Santonian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) formations of the Western Interior of North America". PLOS ONE 12 (11): e0188426. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188426. PMID 29166406. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1288426F.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Sampson, S. D.; Loewen, M. A.; Roberts, E. M.; Getty, M. A. (2013). "A new macrovertebrate assemblage from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Southern Utah". At the Top of the Grand Staircase: The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 599–622. ISBN 978-0-253-00883-1.

- ↑ Roberts, E. M.; Sampson, S. D.; Deino, A. L.; Bowring, S. A.; Buchwaldt, S. (2013). "The Kaiparowits Formation: a remarkable record of Late Cretaceous terrestrial environments, ecosystems, and evolution in Western North America". At the Top of the Grand Staircase: The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 85–106. ISBN 978-0-253-00883-1.

- ↑ Titus, A. L.; Eaton, J. G.; Sertich, J. (2016). "Late Cretaceous stratigraphy and vertebrate faunas of the Markagunt, Paunsaugunt, and Kaiparowits plateaus, southern Utah". Geology of the Intermountain West 3: 229–291. doi:10.31711/giw.v3i0.10.

- ↑ Wiersma, J. P.; Irmis, R. B. (2018). "A new southern Laramidian ankylosaurid, Akainacephalus johnsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the upper Campanian Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah, USA". PeerJ 6: 76. doi:10.7717/peerj.5016. PMID 30065856.

- ↑ Oser, S. E. (2018). Campanian ooassemblages within the Western Interior Basin: eggshell from the Upper Cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation of Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, UT (MSc thesis). Boulder: Department of Museum and Field Studies, University of Colorado. S2CID 134887908.

External links

- Meet Nasutoceratops: Big-Nose Horned Face - 11 minute NPR audio interview with describer Scott D. Sampson

- NHMU's Nasutoceratops features in Jurassic World Dominion - 4 minute video interview with curator Randall Irmis

- Battle at Big Rock - 10 minute Jurasic World short film featuring Nasutoceratops

Wikidata ☰ Q3914791 entry

|