Biology:Nociception

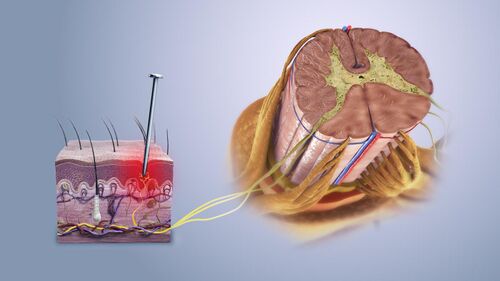

In physiology, nociception (/ˌnəʊsɪˈsɛpʃ(ə)n/), also nocioception; from la nocere 'to harm/hurt') is the sensory nervous system's process of encoding noxious stimuli. It deals with a series of events and processes required for an organism to receive a painful stimulus, convert it to a molecular signal, and recognize and characterize the signal to trigger an appropriate defensive response.

In nociception, intense chemical (e.g., capsaicin present in chili pepper or cayenne pepper), mechanical (e.g., cutting, crushing), or thermal (heat and cold) stimulation of sensory neurons called nociceptors produces a signal that travels along a chain of nerve fibers via the spinal cord to the brain.[1] Nociception triggers a variety of physiological and behavioral responses to protect the organism against an aggression, and usually results in a subjective experience, or perception, of pain in sentient beings.[2]

Detection of noxious stimuli

Potentially damaging mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli are detected by nerve endings called nociceptors, which are found in the skin, on internal surfaces such as the periosteum, joint surfaces, and in some internal organs. Some nociceptors are unspecialized free nerve endings that have their cell bodies outside the spinal column in the dorsal-root ganglia.[3] Others are specialised structures in the skin such as nociceptive schwann cells.[4] Nociceptors are categorized according to the axons which travel from the receptors to the spinal cord or brain. After nerve injury it is possible for touch fibres that normally carry non-noxious stimuli to be perceived as noxious.[5]

Nociceptive pain consists of an adaptive alarm system.[6] Nociceptors have a certain threshold; that is, they require a minimum intensity of stimulation before they trigger a signal. Once this threshold is reached, a signal is passed along the axon of the neuron into the spinal cord.

Nociceptive threshold testing deliberately applies a noxious stimulus to a human or animal subject to study pain. In animals, the technique is often used to study the efficacy of analgesic drugs and to establish dosing levels and period of effect. After establishing a baseline, the drug under test is given and the elevation in threshold recorded at specified times. When the drug wears off, the threshold should return to the baseline (pretreatment) value. In some conditions, excitation of pain fibers becomes greater as the pain stimulus continues, leading to a condition called hyperalgesia.

Theory

Consequences

Nociception can also cause generalized autonomic responses before or without reaching consciousness to cause pallor, sweating, tachycardia, hypertension, lightheadedness, nausea, and fainting.[7]

System overview

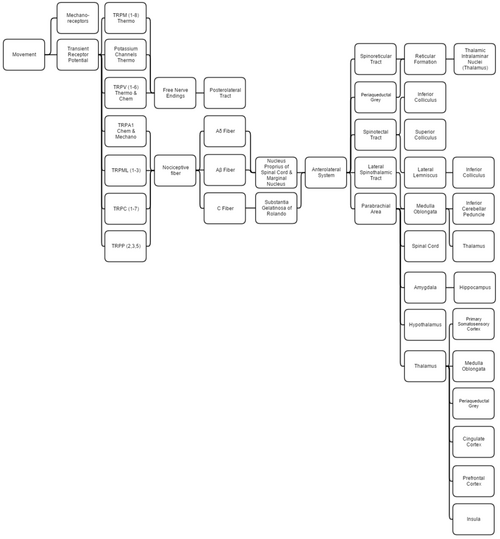

This overview discusses proprioception, thermoception, chemoception, and nociception, as they are all integrally connected.

Mechanical

Proprioception is determined by using standard mechanoreceptors (especially ruffini corpuscles (stretch) and transient receptor potential channels (TRP channels). Proprioception is completely covered within the somatosensory system, as the brain processes them together.

Thermoception refers to stimuli of moderate temperatures 24–28 °C (75–82 °F), as anything beyond that range is considered pain and moderated by nociceptors. TRP and potassium channels [TRPM (1-8), TRPV (1-6), TRAAK, and TREK] each respond to different temperatures (among other stimuli), which create action potentials in nerves that join the mechano (touch) system in the posterolateral tract. Thermoception, like proprioception, is then covered by the somatosensory system.[8][9][10][11][12]

TRP channels that detect noxious stimuli (mechanical, thermal, and chemical pain) relay that information to nociceptors that generate an action potential. Mechanical TRP channels react to depression of their cells (like touch), thermal TRPs change shape in different temperatures, and chemical TRPs act like taste buds, signalling if their receptors bond to certain elements/chemicals.

Neural

- Laminae 3-5 make up nucleus proprius in spinal grey matter.

- Lamina 2 makes up substantia gelatinosa of Rolando, unmyelinated spinal grey matter. Substantia receives input from nucleus proprius and conveys intense, poorly localized pain.

- Lamina 1 primarily project to the parabrachial area and periaqueductal grey, which begins the suppression of pain via neural and hormonal inhibition. Lamina 1 receive input from thermoreceptors via the posterolateral tract. Marginal nucleus of the spinal cord are the only unsuppressible pain signals.

- The parabrachial area integrates taste and pain info, then relays it. Parabrachial checks if the pain is being received in normal temperatures and if the gustatory system is active; if both are so the pain is assumed to be due to poison.

- Ao fibers synapse on laminae 1 and 5 while Ab synapses on 1, 3, 5, and C. C fibers exclusively synapse on lamina 2.[13][14]

- The amygdala and hippocampus create and encode the memory and emotion due to pain stimuli.

- The hypothalamus signals for the release of hormones that make pain suppression more effective; some of these are sex hormones.

- Periaqueductal grey (with hypothalamic hormone aid) hormonally signals reticular formation's raphe nuclei to produce serotonin that inhibits laminae pain nuclei.[15]

- Lateral spinothalamic tract aids in localization of pain.

- Spinoreticular and spinotectal tracts are merely relay tracts to the thalamus that aid in the perception of pain and alertness towards it. Fibers cross over (left becomes right) via the spinal anterior white commissure.

- Lateral lemniscus is the first point of integration of sound and pain information.[16]

- Inferior colliculus (IC) aids in sound orienting to pain stimuli.[17]

- Superior colliculus receives IC's input, integrates visual orienting info, and uses the balance topographical map to orient the body to the pain stimuli.[18][19]

- Inferior cerebellar peduncle integrates proprioceptive info and outputs to the vestibulocerebellum. The peduncle is not part of the lateral-spinothalamic-tract-pathway; the medulla receives the info and passes it onto the peduncle from elsewhere (see somatosensory system).

- The thalamus is where pain is thought to be brought into perception; it also aids in pain suppression and modulation, acting like a bouncer, allowing certain intensities through to the cerebrum and rejecting others.[20]

- The somatosensory cortex decodes nociceptor info to determine the exact location of pain and is where proprioception is brought into consciousness; inferior cerebellar peduncle is all unconscious proprioception.

- Insula judges the intensity of the pain and provides the ability to imagine pain.[21][22]

- Cingulate cortex is presumed to be the memory hub for pain.[23]

In non-mammals

Nociception has been documented in other animals, including fish[24] and a wide range of invertebrates,[25] including leeches,[26] nematode worms,[27] sea slugs,[28] and fruit flies.[29] As in mammals, nociceptive neurons in these species are typically characterized by responding preferentially to high temperature (40 °C or more), low pH, capsaicin, and tissue damage.

History of term

The term "nociception" was coined by Charles Scott Sherrington to distinguish the physiological process (nervous activity) from pain (a subjective experience).[30] It is derived from the Latin verb nocēre, which means "to harm".

See also

References

- ↑ Portenoy, Russell K.; Brennan, Michael J. (1994). "Chronic Pain Management". in Good, David C.; Couch, James R.. Handbook of Neurorehabilitation. Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-0-8247-8822-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=1RGIDl4OP0IC&pg=RA3-PA403. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Bayne, Kathryn (2000). "Assessing Pain and Distress: A Veterinary Behaviorist's Perspective". Definition of Pain and Distress and Reporting Requirements for Laboratory Animals: Proceedings of the Workshop Held June 22, 2000. National Academies Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 978-0-309-17128-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99551/. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ↑ Purves, D. (2001). "Nociceptors". in Sunderland, MA.. Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10965/. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Doan, Ryan A.; Monk, Kelly R. (16 August 2019). "Glia in the skin activate pain responses". Science 365 (6454): 641–642. doi:10.1126/science.aay6144. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 31416950. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365..641D.

- ↑ Dhandapani, Rahul; Arokiaraj, Cynthia Mary; Taberner, Francisco J.; Pacifico, Paola; Raja, Sruthi; Nocchi, Linda; Portulano, Carla; Franciosa, Federica et al. (2018-04-24). "Control of mechanical pain hypersensitivity in mice through ligand-targeted photoablation of TrkB-positive sensory neurons" (in en). Nature Communications 9 (1): 1640. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04049-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 29691410. Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9.1640D.

- ↑ Woolf, Clifford J.; Ma, Qiufu (2007-08-02). "Nociceptors--noxious stimulus detectors". Neuron 55 (3): 353–364. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.016. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 17678850.

- ↑ Feinstein, B.; Langton, J. N. K.; Jameson, R. M.; Schiller, F. (October 1954). "Experiments on pain referred from deep somatic tissues". The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 36 (5): 981–997. doi:10.2106/00004623-195436050-00007. PMID 13211692.

- ↑ McCann, Stephanie (2017). Kaplan Medical Anatomy Flashcards: Clearly Labeled, Full-Color Cards. KAPLAN. ISBN 978-1-5062-2353-7.[page needed]

- ↑ Albertine, Kurt. Barron's Anatomy Flash Cards[page needed]

- ↑ Hofmann, Thomas; Schaefer, Michael; Schultz, Günter; Gudermann, Thomas (28 May 2002). "Subunit composition of mammalian transient receptor potential channels in living cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (11): 7461–7466. doi:10.1073/pnas.102596199. PMID 12032305. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.7461H.

- ↑ Noël, Jacques; Zimmermann, Katharina; Busserolles, Jérome; Deval, Emanuel; Alloui, Abdelkrim; Diochot, Sylvie; Guy, Nicolas; Borsotto, Marc et al. (12 March 2009). "The mechano-activated K+ channels TRAAK and TREK-1 control both warm and cold perception". The EMBO Journal 28 (9): 1308–1318. doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.57. PMID 19279663.

- ↑ Scholz, Joachim; Woolf, Clifford J. (November 2002). "Can we conquer pain?". Nature Neuroscience 5 (11): 1062–1067. doi:10.1038/nn942. PMID 12403987.

- ↑ Braz, Joao M.; Nassar, Mohammed A.; Wood, John N.; Basbaum, Allan I. (September 2005). "Parallel 'Pain' Pathways Arise from Subpopulations of Primary Afferent Nociceptor". Neuron 47 (6): 787–793. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.015. PMID 16157274.

- ↑ Brown, A. G. (2012). Organization in the Spinal Cord: The Anatomy and Physiology of Identified Neurones. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4471-1305-8.[page needed]

- ↑ van den Pol, Anthony N. (15 April 1999). "Hypothalamic Hypocretin (Orexin): Robust Innervation of the Spinal Cord". The Journal of Neuroscience 19 (8): 3171–3182. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03171.1999. PMID 10191330.

- ↑ Bajo, Victoria M.; Merchán, Miguel A.; Malmierca, Manuel S.; Nodal, Fernando R.; Bjaalie, Jan G. (10 May 1999). "Topographic organization of the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus in the cat". The Journal of Comparative Neurology 407 (3): 349–366. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990510)407:3<349::AID-CNE4>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 10320216.

- ↑ Oliver, Douglas L. (2005). "Neuronal Organization in the Inferior Colliculus". The Inferior Colliculus. pp. 69–114. doi:10.1007/0-387-27083-3_2. ISBN 0-387-22038-0.

- ↑ Corneil, Brian D.; Olivier, Etienne; Munoz, Douglas P. (1 October 2002). "Neck Muscle Responses to Stimulation of Monkey Superior Colliculus. I. Topography and Manipulation of Stimulation Parameters". Journal of Neurophysiology 88 (4): 1980–1999. doi:10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1980. PMID 12364523.

- ↑ May, Paul J. (2006). "The mammalian superior colliculus: Laminar structure and connections". Neuroanatomy of the Oculomotor System. Progress in Brain Research. 151. pp. 321–378. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51011-2. ISBN 9780444516961.

- ↑ Benevento, Louis A.; Standage, Gregg P. (1 July 1983). "The organization of projections of the retinorecipient and nonretinorecipient nuclei of the pretectal complex and layers of the superior colliculus to the lateral pulvinar and medial pulvinar in the macaque monkey". The Journal of Comparative Neurology 217 (3): 307–336. doi:10.1002/cne.902170307. PMID 6886056.

- ↑ Sawamoto, Nobukatsu; Honda, Manabu; Okada, Tomohisa; Hanakawa, Takashi; Kanda, Masutaro; Fukuyama, Hidenao; Konishi, Junji; Shibasaki, Hiroshi (1 October 2000). "Expectation of Pain Enhances Responses to Nonpainful Somatosensory Stimulation in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex and Parietal Operculum/Posterior Insula: an Event-Related Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study". The Journal of Neuroscience 20 (19): 7438–7445. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07438.2000. PMID 11007903.

- ↑ Menon, Vinod; Uddin, Lucina Q. (29 May 2010). "Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function". Brain Structure and Function 214 (5–6): 655–667. doi:10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. PMID 20512370.

- ↑ Shackman, Alexander J.; Salomons, Tim V.; Slagter, Heleen A.; Fox, Andrew S.; Winter, Jameel J.; Davidson, Richard J. (March 2011). "The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 12 (3): 154–167. doi:10.1038/nrn2994. PMID 21331082.

- ↑ Sneddon, L. U.; Braithwaite, V. A.; Gentle, M. J. (2003). "Do fishes have nociceptors? Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 270 (1520): 1115–1121. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2349. PMID 12816648.

- ↑ Jane A. Smith (1991). "A Question of Pain in Invertebrates". Institute for Laboratory Animals Journal 33 (1–2). http://www.abolitionist.com/darwinian-life/invertebrate-pain.html. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ Pastor, J.; Soria, B.; Belmonte, C. (1996). "Properties of the nociceptive neurons of the leech segmental ganglion". Journal of Neurophysiology 75 (6): 2268–2279. doi:10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2268. PMID 8793740.

- ↑ Wittenburg, N.; Baumeister, R. (1999). "Thermal avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans: an approach to the study of nociception". PNAS 96 (18): 10477–10482. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.18.10477. PMID 10468634. Bibcode: 1999PNAS...9610477W.

- ↑ Illich, P. A.; Walters, E. T. (1997). "Mechanosensory neurons innervating Aplysia siphon encode noxious stimuli and display nociceptive sensitization". Journal of Neuroscience 17 (1): 459–469. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00459.1997. PMID 8987770.

- ↑ Tracey, W.Daniel; Wilson, Rachel I; Laurent, Gilles; Benzer, Seymour (April 2003). "painless, a Drosophila Gene Essential for Nociception". Cell 113 (2): 261–273. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00272-1. PMID 12705873.

- ↑ Sherrington, C. (1906). The Integrative Action of the Nervous System. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://archive.org/details/integrativeacti00shergoog.[page needed]

|