Biology:Paraceratheriidae

| Paraceratheriidae | |

|---|---|

| |

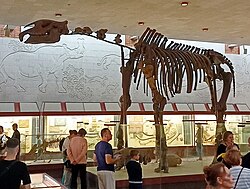

| Skeleton of Paraceratherium | |

| |

| Skeleton of Juxia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Superfamily: | Rhinocerotoidea |

| Family: | †Paraceratheriidae Osborn, 1923 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Paraceratheriidae is an extinct family of long-limbed, hornless rhinocerotoids native to Asia and Eastern Europe[3] that originated in the Eocene epoch and lived until the end of the Oligocene.

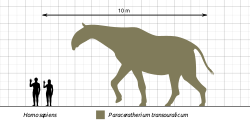

The earliest paraceratheres like Juxia were comparable in size with living rhinoceroses with a body mass of three quarters to one and a half tons, while later members grew substantially larger, with the largest representatives (Paraceratherium, Dzungariotherium) estimated to have a body mass of 17 to possibly over 20 tons, making them the largest land mammals to have ever lived.[4][5]

Their range spanned from Eastern Europe in the west, the Indian Subcontinent in the south, to Northern China in the east.[3]

They are thought to have been primarily browsers.[6]

Although considered a subfamily of the family Hyracodontidae by some authors, recent authors treat the paraceratheres as a distinct family, Paraceratheriidae (Wang et al. 2016 recover hyracodonts as more basal than paraceratheres).[7][8] Paraceratheriidae is generally recovered as the sister group of Rhinocerotidae, the group which contains modern rhinoceroses.[3]

References

- ↑ Lucas, S.G.; Sobus, J.C. (1989). "The Systematics of Indricotheres". in Prothero, D. R.; Schoch, R. M.. The Evolution of Perissodactyls. New York, New York & Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 358–378. ISBN 978-0-19-506039-3. OCLC 19268080. https://books.google.com/books?id=08YPAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Wood, H.E. (1963). "A Primitive Rhinoceros from the Late Eocene of Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (2146): 1–12. http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/index.php?s=1&act=pdfviewer&id=1245598571&folder=124.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Deng, Tao; Lu, Xiaokang; Wang, Shiqi; Flynn, Lawrence J.; Sun, Danhui; He, Wen; Chen, Shanqin (2021-06-17). "An Oligocene giant rhino provides insights into Paraceratherium evolution" (in en). Communications Biology 4 (1). doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02170-6. ISSN 2399-3642. PMID 34140631. PMC 8211792. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-021-02170-6.

- ↑ Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. https://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app61/app001362014.pdf.

- ↑ Li, Shijie; Jiangzuo, Qigao; Deng, Tao (2022-07-06). "Body mass of the giant rhinos (Paraceratheriinae, Mammalia) and its tendency in evolution" (in en). Historical Biology: 1–12. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2095908. ISSN 0891-2963. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08912963.2022.2095908.

- ↑ Martin, C.; Bentaleb, I.; Antoine, P. -O. (2011). "Pakistan mammal tooth stable isotopes show paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental changes since the early Oligocene". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 311 (1–2): 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.07.010. Bibcode: 2011PPP...311...19M.

- ↑ Z. Qiu and B. Wang. 2007. Paracerathere Fossils of China. Palaeontologia Sinica, New Series C 193(29):1-396

- ↑ Wang, H.; Bai, B.; Meng, J.; Wang, Y. (2016). "Earliest known unequivocal rhinocerotoid sheds new light on the origin of Giant Rhinos and phylogeny of early rhinocerotoids". Scientific Reports 6 (1): 39607. doi:10.1038/srep39607. PMID 28000789.

Wikidata ☰ Q1094909 entry

|