Biology:Sinhapura

Sinhapura (Sanskrit, "Lion City"; IAST: Siṃhapura) was the capital of the legendary Indian king Sinhabahu. It has been mentioned in the Buddhist legends about Prince Vijaya. The name is also transliterated as Sihapura or Singhapura.

The location of Sinhapura is disputed with some scholars claiming the city was located in eastern India and others claiming it was located in present-day Malaysia or Thailand.[1] The city is linked to the origin of the Sinhalese people and Sinhalese Buddhist mythology.

The legend

According to Mahavamsa, the king of Vanga (historic Bengal region) married the daughter of the king of Kalinga (present-day Odisha). The couple had a daughter named Suppadevi, who was prophesied to copulate with the king of beasts. As an adult, Princess Suppadevi left Vanga to seek an independent life. She joined a caravan headed for Magadha, but it was attacked by Sinha ("lion") in a forest of the Lala (or Lada) region. The Mahavamsa mentions the "Sinha" as an animal, but some modern interpreters state that Sinha was the name of a beastly outlaw man living in the jungle. Lala is variously identified as Rarh (an area in the Vanga-Kalinga region), or as Lata (a part of the present-day Gujarat).[2][3]

Suppadevi fled during the attack, but encountered Sinha again. Sinha was attracted to her, and she also caressed him, thinking of the prophecy. Sinha kept Suppadevi locked in a cave, and had two children with her: a son named Sinhabahu (or Sihabahu; "lion-armed") and a daughter named Sinhasivali (or Sihasivali). When the children grew up, Suppadevi escaped with them to Vanga. They met a general who happened to be a cousin of Suppadevi, and later married her. Meanwhile, Sinha started ravaging villages in an attempt to find his missing family. The King of Vanga announced a reward for anyone who could kill Sinha. Sinhabahu killed his own father to claim the reward. By the time Sinhabahu returned to the capital, the King of Vanga had died. Sinhabhau was declared the new king by the ministers, but he later handed over the kingship to his mother's husband, the general. He went back to his birthplace in Lala, and founded the city of Sinhapura.[2][4]

Sinhabahu married his sister Sinhasivali, and the couple had 32 sons in form of 16 pairs of twins. Vijaya was their eldest son, followed by his twin Sumitta. Vijaya and his followers were expelled from Sinhapura for their violent deeds against the citizens. During their exile, they reached the present-day Sri Lanka, where they found the Kingdom of Tambapanni. Meanwhile, in Sinhapura, Sumitta succeeded his father as the king. Before an heirless Vijaya died in Lanka, he sent a letter to Sumitta, asking him to come to Lanka and govern the new kingdom. Sumitta was too old to go to Lanka, so he sent his youngest son Panduvasdeva instead.[2]

Identification

Mahavamsa mentions that Sinhapura was founded in Lala, but doesn't mention the exact location of Lala. Scholars who believe the legend of Prince Vijaya to be semi-historical have tried to identify the legendary Sinhapura with several modern places in India.

According to one theory, Sinhapura was in Present day southern part of WEST BENGAL, a place named Singur which is a census town in Singur CD Block in Chandannagore subdivision of Hooghly district, or another legend say this was in Kalinga, either in present-day Odisha, Jharkhand or the northern part of Andhra Pradesh. A city named Simhapura (another variant of "lion city") was the capital of Kalinga region during Mathara, Pitrubhakta and Vasistha dynasties.[5][6] The inscriptions of three Kalinga kings — Candavarman, Umavarman and Ananta Saktivarman — were issued from Simhapura. Ananta Saktivarman's inscription is dated approximately to 5th century CE on paleographic grounds.[7] A Sanskrit-language plate inscription, also dated approximately to 5th century CE, mentions that it was issued by a vassal king named Satrudamanadeva from the Simhapura city. The inscription was found at Pedda Dugam, a place in Jalumuru mandal of Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh.[8] Simhapura was the capital of a kingdom in Kalinga region in as late as 12th century CE.[7] The inscriptions of the Sri Lankan king Nissanka Malla state that he was born in Sinhapura of Kalinga in 1157/8 CE, and that he was a descendant of Vijaya. However, his records are considered to be boastful exaggerations.[9]

R. C. Majumdar mentions that the Kalinga capital Simhapura and Sinhapura of Mahavamsa may have been same, but "the whole story is too legendary to be considered seriously".[7] Even those who identify Sinhapura with Simhapura of Kalinga differ in opinion about its exact location. One source identifies the ancient city with the Singupuram village near Srikakulam in Andhra Pradesh.[10] Another source identifies Sinhapura with Singhpur town near Jajpur in present-day Odisha.[3]

Professor Manmath Nath Das points out that according to Mahavamsa, Lala (and therefore Sinhapura) was located on the way from Vanga (present-day Bengal) to Magadha (present-day Bihar). If Mahavamsa is correct, Sinhapura could not have been located in today's Odisha or Andhra Pradesh, because these places lie to the south of Bengal, away from Bihar. He, therefore, concludes that the Sinhapura of Mahavamsa was different from the capital city mentioned in records of Kalinga's rulers: it was probably located in the present-day Chota Nagpur area.[11] S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar also believed that Lala and Sinhapura were located on road main road connecting Vanga to Magadha. According to him, this area was either a part of the Kalinga kingdom, or located near its border.[12]

Historians such as A. L. Basham and Senarath Paranavithana believe that the Lala kingdom was situated far away from the Vanga-Kalinga region, in present-day Gujarat. According to them, Sinhapura was located in present-day Sihor.[13]

According to Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri, Sinhapura was in the Rarh region of Vanga. He identifies it with the present-day Singur in West Bengal.[14]

Other scholars claim the city was located in Southeast Asia. Paranavitana indirectly claimed the city was located in Malaya while Rohanadheera claimed the city was Sing Buri, close to the city of Lopburi, which was located within the Khmer Empire at the time.[1]

Genetic Studies

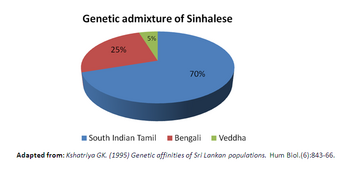

According to a genetic admixture study by Dr. Gautam K. Kshatriya in 1995, the Sri Lankan Tamil are closely related to the Sinhalese who are closely related to Indian Tamils. Kshatriya found the Sri Lankan Tamils to have a greater contribution from the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka (55.20% +/- 9.47) while the Sinhalese had the greatest contribution from South Indian Tamils (69.86% +/- 0.61), followed by Bengalis from the East India (25.41% +/- 0.51). With both the Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhalese in the island sharing a common gene pool of 55%. They are farthest from the indigenous Veddahs.[15] This close relationship between the Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhalese makes sense, as the two populations have been close to each other historically, linguistically, and culturally for over 2000 years.[15]

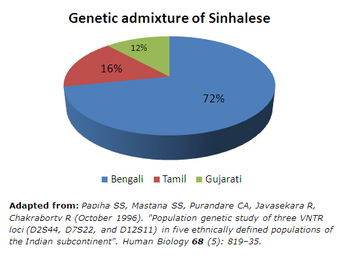

This is also supported by a genetic distance study, which showed low differences in genetic distance between Tamils and the Sinhalese.[16] Tamils and the Sinhalese also share similar cultures in terms of kinship classification, cousin marriage, dress and housing.[17] The observation that the Sinhalese has highest contribution from South Indian Tamils is challenged by new studies. See Genetic studies on Sinhalese. It is shown that 72% of genetic admixture comes from Bengali rather than South Indian Tamil, which unconditionally rejected the theory of orissa connection of simhapura.

Relationship to Bengalis

An Alu polymorphism analysis of Sinhalese from Colombo by Dr Sarabjit Mastanain in 2007 using Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati (Patel), and Punjabi as parental populations found different proportions of genetic contribution:[18]

| Statistical Method | Bengali | Tamil | North Western |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate | 57.49% | 42.5% | - |

| Maximum Likelihood Method | 88.07% | - | - |

| Using Tamil, Bengali and North West as parenteral population | 50-66% | 11-30% | 20-23% |

A genetic distance analysis by Dr Robet Kirk also concluded that the modern Sinhalese are most closely related to the Bengalis.[16]

This is further substantiated by a VNTR study, which found 70-82% of Sinhalese genes to originate from Bengali admixture:[19]

| Parenteral population | Bengali | Tamil | Gujarati | Punjabi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using Tamil and Bengali as parenteral population | 70.03% | 29.97% | - | |

| Using Tamil, Bengali and Gujarati as parenteral population | 71.82% | 16.38% | 11.82% | |

| Using Bengali, Gujarati and Punjabi as parenteral population | 82.09% | - | 15.39% | 2.52% |

D1S80 allele frequency (A popular allele for genetic fingerprinting) is also similar between the Sinhalese and Bengalis, suggesting the two groups are closely related.[20] The Sinhalese also have similar frequencies of the allele MTHFR 677T (13%) to West Bengalis (17%).[21][22]

A test for Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups conducted by Dr Toomas Kivisild on Sinhalese of Sri Lanka has shown that 23% of the subjects were R1a1a (R-SRY1532) positive.[23] Also in the same test 24.1% of the subjects were R2 positive as subclades of Haplogroup P (92R7).[23] Haplogroup R2 is also found in a considerable percentage among Bengali of India.

Relationship to other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka

A study looking at genetic variation of the FUT2 gene in the Sinhalese and Sri Lankan Tamil population, found similar genetic backgrounds for both ethnic groups, with little genetic flow from other neighbouring Asian population groups.[24] Studies have also found no significant difference with regards to blood group, blood genetic markers and single-nucleotide polymorphism between the Sinhalese and other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka.[25][26][27] Another study has also found "no significant genetic variation among the major ethnic groups in Sri Lanka".[28] This is further supported by a study which found very similar frequencies of alleles MTHFR 677T, F2 20210A & F5 1691A in South Indian Tamil, Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamil and Moor populations.[22]

Relationship to East and Southeast Asians

Genetic studies show that the Sinhalese have received some genetic flow from neighboring populations in East Asia and Southeast Asia, such as from the ethnically diverse and disparate Tibeto-Burman peoples and Austro-Asiatic peoples,[29] which is due to their close genetic links to Northeast India.[30][31][32] A 1985 study conducted by Roychoudhury AK and Nei M, indicated the values of genetic distance showed that the Sinhalese people were slightly closer to Mongoloid populations due to gene exchange in the past.[33][34] In regards to comparisons of root and canal morphology of Sri Lankan mandibular molars, it showed that they were further away from Mongoloid populations.[35] Among haplogroups found in East Asian populations, a lower frequency of East Asian mtDNA haplogroup, G has been found among the populations of Sri Lanka alongside haplogroup D in conjunction with the main mtDNA haplogroup of Sri Lanka's ethnic groups, haplogroup M.[36] In regards to Y-DNA, Haplogroup C-M130 is found at low to moderate frequencies in Sri Lanka.[37]

Genetic markers of immunoglobulin among the Sinhalese show high frequencies of afb1b3 which has its origins in the Yunnan and Guangxi provinces of southern China.[38] It is also found at high frequencies among Odias, certain Nepali and Northeast Indian, southern Han Chinese, Southeast Asian and certain Austronesian populations of the Pacific Islands.[38] At a lower frequency, ab3st is also found among the Sinhalese and is generally found at higher frequencies among northern Han Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian, Korean and Japanese populations.[38] The Transferrin TF*Dchi allele which is common among East Asian and Native American populations is also found among the Sinhalese.[33] HumDN1*4 and HumDN1*5 are the predominant DNase I genes among the Sinhalese and are also the predominant genes among southern Chinese ethnic groups and the Tamang people of Nepal.[39] A 1988 study conducted by N. Saha, showed the high GC*1F and low GC*1S frequencies among the Sinhalese are comparable to those of the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Thais, Malays, Vietnamese, Laotians and Tibetans.[40] A 1998 study conducted by D.E. Hawkey showed dental morphology of the Sinhalese is closely related to those of the Austro-Asiatic populations of East and Northeast India.[29] Hemoglobin E a variant of normal hemoglobin, which originated in and is prevalent among populations in Southeast Asia, is also common among the Sinhalese and can reach up to 40% in Sri Lanka.[41]

Skin pigmentation

In 2008 a study looked at SLC24A5 polymorphism which accounts for 25-40% of the skin complexion difference between Europeans and Africans and up to 30% of skin colour variation in South Asians.[42] The study found that the rs1426654 SNP of SLC24A5, which is fixed in European populations[43] and found more commonly in light skinned individuals than dark skinned individuals (49% compared to 10%), has a frequency of 50-55% in the Sinhalese and 25-30% in Sri Lankan Tamils.[42] This allele could have arisen in the Sinhalese due to strong East Asian genetic admixture, further migration from North India or strong selection factors.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K; Sakhuja, Vijay (2009). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa : reflections on the Chola naval expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 201. ISBN 978-981-230-937-2.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 John M. Senaveratna (1997). The story of the Sinhalese from the most ancient times up to the end of "the Mahavansa" or Great dynasty. Asian Educational Services. pp. 7–22. ISBN 978-81-206-1271-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=X9TeEcMi0e0C&lpg=PA21&pg=PA7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Mudaliyar C. Rasanayagam (1984). Ancient Jaffna. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120602106. https://books.google.ca/books?id=k9DpMY206bMC&lpg=PA51&pg=PA51.

- ↑ "The Coming of Vijaya". The Mahavamsa. http://mahavamsa.org/mahavamsa/original-version/06-coming-vijaya/. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ The Orissa Historical Research Journal. Superintendent of Research and Museum. 1990. p. 152. https://books.google.com/books?id=iw5DAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ Snigdha Tripathy (1 January 1997). Inscriptions of Orissa: Circa 5th-8th centuries A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-208-1077-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=XUiYu3XByNgC&pg=PA26.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 R. C. Majumdar (1996). Outline of the history of Kaliṅga. Asian Educational Services. pp. 4–7. ISBN 81-206-1194-2. https://books.google.ca/books?id=LNCcpkqesJ0C&pg=PA6.

- ↑ Snigdha Tripathy (1 January 1997). Inscriptions of Orissa: Circa 5th-8th centuries A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-81-208-1077-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=XUiYu3XByNgC&pg=PA131.

- ↑ H. W. Codrington (1 January 1994). Short History of Ceylon. Asian Educational Services. pp. 65. ISBN 978-81-206-0946-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=tqpdlaPiOyEC&pg=PA65.

- ↑ Nihar Ranjan Patnaik (1997). Economic History of Orissa. Indus Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-81-7387-075-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=1AA9W9_4Z9gC&pg=PA66.

- ↑ Manmath Nath Das (1977). Sidelights on History and Culture of Orissa. Vidyapuri. p. 124. https://books.google.com/books?id=VsQBAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar (1 January 1995). Some Contributions of South India to Indian Culture. Asian Educational Services. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-81-206-0999-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=vRcql-QBhRwC&pg=PA75.

- ↑ Dr. Sripali Vaiamon (2012). Pre-historic Lanka to end of Terrorism. Trafford. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4669-1245-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=AYBXAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT169.

- ↑ Harihar Panda (2007). Professor H.C. Raychaudhuri, as a Historian. Northern Book Centre. p. 112. ISBN 978-81-7211-210-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=f1XMtc2Q97IC&pg=PA112.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Kshatriya, G.K. (1995). "Genetic affinities of Sri Lankan populations". Human Biology (American Association of Anthropological Genetics) 67 (6): 843–66. PMID 8543296.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Kirk, R. L. (1976). "The legend of Prince Vijaya — a study of Sinhalese origins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 45 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450112.

- ↑ Yalman, Nur (1 January 1962). "The Structure of the Sinhalese Kindred: A Re-Examination of the Dravidian Terminology". American Anthropologist 64 (3): 548–575. doi:10.1525/aa.1962.64.3.02a00060.

- ↑ http://www.krepublishers.com/06-Special%20Volume-Journal/T-Anth-00-Special%20Volumes/T-Anth-SI-03-Anth-Today-Web/Anth-SI-03-29-Mastana-S/Anth-SI-03-29-Mastana-S-Tt.pdf

- ↑ "Population genetic study of three VNTR loci (D2S44, D7S22, and D12S11) in five ethnically defined populations of the Indian subcontinent". Human Biology 68 (5): 819–35. October 1996. PMID 8908803.

- ↑ Surinder Singh Papiha (1999). Genomic Diversity: Applications in Human Population Genetics. London: Springer. 7.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay, 2007 K. Mukhopadhyay et al., MTHFR gene polymorphisms analyzed in population from Kolkata, West Bengal, Indian J. Human Genet. 13 (2007), p. 38.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 Vajira H.W. Dissanayake, Lakshini Y. Weerasekera, C. Gayani Gammulla, Rohan W. Jayasekara, Prevalence of genetic thrombophilic polymorphisms in the Sri Lankan population -- implications for association study design and clinical genetic testing services, Experimental and Molecular Pathology, Volume 87, Issue 2, October 2009, Pages 159-162

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Kivisild, Toomas (2003). "The Genetics of Language and Farming Spread in India". in Bellwood P, Renfrew C.. Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. pp. 215–222. http://evolutsioon.ut.ee/publications/Kivisild2003a.pdf.

- ↑ "Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography-based genotyping and genetic variation of FUT2 in Sri Lanka". Transfusion 45 (12): 1934–9. December 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00651.x. PMID 16371047.

- ↑ Saha, N. (1988). "Blood genetic markers in Sri Lankan populations—reappraisal of the legend of Prince Vijaya". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 76 (2): 217–25. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330760210. PMID 3166342.

- ↑ D. F. Roberts, C. K. Creen, K. P. Abeyaratne, Man, New Series, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Mar., 1972), pp. 122-127, Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2799860

- ↑ "A study of three candidate genes for pre-eclampsia in a Sinhalese population from Sri Lanka". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 35 (2): 234–42. April 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00926.x. PMID 19708171.

- ↑ Ruwan J. Illeperuma, Samudi N. Mohotti, Thilini M. De Silva, Neil D. Fernandopulle, W.D. Ratnasooriya, Genetic profile of 11 autosomal STR loci among the four major ethnic groups in Sri Lanka, Forensic Science International: Genetics, Volume 3, Issue 3, June 2009, Pages e105-e106

- ↑ Jump up to: 29.0 29.1 Hawkey, D E (1998). Out of Asia: Dental evidence for affinity and microevolution of early and recent populations of India and Sri Lanka. ISBN 9781402055621. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qm9GfjNlnRwC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Soejima, Mikiko; Koda, Yoshiro (2006). "Population differences of two coding SNPs in pigmentation-related genes SLC24A5 and SLC45A2". International Journal of Legal Medicine 121 (1): 36–9. doi:10.1007/s00414-006-0112-z. PMID 16847698.

- ↑ "The genetic heritage of the earliest settlers persists both in Indian tribal and caste populations". American Journal of Human Genetics 72 (2): 313–32. 2003. doi:10.1086/346068. PMID 12536373.

- ↑ "Polarity and temporality of high-resolution y-chromosome distributions in India identify both indigenous and exogenous expansions and reveal minor genetic influence of Central Asian pastoralists". American Journal of Human Genetics 78 (2): 202–21. 2006. doi:10.1086/499411. PMID 16400607.

- ↑ Jump up to: 33.0 33.1 Roychoudhury AK; Nei M (1985). "Genetic relationships between Indians and their neighboring populations". Hum Hered 35 (4): 201–6. doi:10.1159/000153545. PMID 4029959. http://php.scripts.psu.edu/nxm2/1985%20Publications/1985-roychoudhury-nei.pdf.

- ↑ M. K. Bhasin (2009). "Morphology to Molecular Anthropology: Castes and Tribes of India". Int J Hum Genet 9 (3–4): 145–230. doi:10.1080/09723757.2009.11886070. http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/IJHG/IJHG-09-0-000-09-Web/IJHG-09-3-4-000-09-Abst-PDF/IJHG-09-3-4-145-09-Bhasin-M-K/IJHG-09-3-4-145-09-Bhasin-M-K-Tt.pdf.

- ↑ Peiris, Roshan; Takahashi, Masami; Sasaki, Kayoko; Kanazawa, Eisaku (2007). "Root and canal morphology of permanent mandibular molars in a Sri Lankan population". Odontology 95 (1): 16–23. doi:10.1007/s10266-007-0074-8. PMID 17660977.

- ↑ Ranaweera, Lanka; Kaewsutthi, Supannee; Win Tun, Aung; Boonyarit, Hathaichanoke; Poolsuwan, Samerchai; Lertrit, Patcharee (2014). "Mitochondrial DNA history of Sri Lankan ethnic people: Their relations within the island and with the Indian subcontinental populations". Journal of Human Genetics 59 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.112. PMID 24196378.

- ↑ "Y-DNA Haplogroup C and its Subclades - 2017". International Society of Genetic Genealogy. http://isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_HapgrpC.html.

- ↑ Jump up to: 38.0 38.1 38.2 Hideo Matsumoto (2009). "The origin of the Japanese race based on genetic markers of immunoglobulin G". Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 85 (2): 69–82. doi:10.2183/pjab.85.69. PMID 19212099.

- ↑ Fujihara, J; Yasuda, T; Iida, R; Ueki, M; Sano, R; Kominato, Y; Inoue, K; Kimura-Kataoka, K et al. (2015). "Global analysis of genetic variations in a 56-bp variable number of tandem repeat polymorphisms within the human deoxyribonuclease I gene". Leg Med (Tokyo) 17 (4): 283–6. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2015.01.005. PMID 25771153.

- ↑ Malhotra, Rikshesh (1992). Anthropology of Development: Commemoration Volume in the Honour of Professor I.P. Singh. ISBN 9788170993285. https://books.google.com/books?id=U6WhkmvI324C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Kumar, Dhavendra (2012-09-15). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. ISBN 9781402022319. https://books.google.com/books?id=2grSBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Jump up to: 42.0 42.1 "Population differences of two coding SNPs in pigmentation-related genes SLC24A5 and SLC45A2". International Journal of Legal Medicine 121 (1): 36–9. January 2007. doi:10.1007/s00414-006-0112-z. PMID 16847698.

- ↑ Stanford University. (2009). rs1426654 Chromosome chr15:46213776. Available: http://hgdp.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/alfreqs.cgi?pos=46213776&chr=chr15&rs=rs1426654&imp=true. Last accessed 3 March 2010.