Biology:Spruce budworm

| Spruce budworm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mountain-ash tortricid Choristoneura hebenstreitella | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Tortricidae |

| Tribe: | Archipini |

| Genus: | Choristoneura Lederer, 1859 |

| Species | |

|

Several, see text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

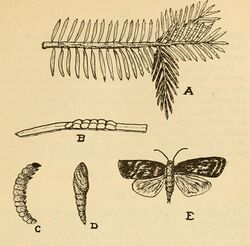

Spruce budworms and relatives are a group of closely related insects in the genus Choristoneura. Most are serious pests of conifers, such as spruce. There are nearly forty Choristoneura species, and even more subspecies, or forms, with a complexity of variation among populations found throughout much of the United States and Canada , and about again this number in Eurasia. In Eastern North America, Choristoneura fumiferana is prevalent, while in Western North America Choristoneura freemani has devastated large areas.

History

The first recorded outbreak of the (eastern) spruce budworm in the United States occurred in Maine in about 1807, although it seems to have escaped notice of the entomologists until 1865. Another outbreak followed in 1878. Since 1909 there have been waves of budworm outbreaks throughout the eastern United States and Canada. Longer-term tree-ring studies suggest that spruce budworm outbreaks have been recurring approximately every three decades since the 16th century.[1]

The first recorded outbreak of the western variety, which was in 2008 from occidentalis rechristened freemani, occurred in 1909 on the southeastern part of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. Since that year, infestations have frequently been reported in western Canada. The budworm was first recorded in 1914 in the United States, in Oregon. However, it was not initially recognized as a serious threat to coniferous forests in the western U.S.[2]

In Atlantic Canada, the spruce budworm problem was noted as early as 1910.[3]

In locations such as New Brunswick, DDT pesticide was applied to over 3.6 million hectares from 1952 to 1958 and 1960 to 1967. This use of chemical control effectively decreased the spruce mortality rate within this area and prevented significant economic impact.[4] In fact, the government of New Brunswick formed Forest Protection Limited (FPL) as an agent with which "to fight the spruce budworm [which was] then threatening to destroy much of New Brunswick's fir-spruce forest".[5]

The Nova Scotia island of Cape Breton was also affected by the 1952 outbreak, but they chose not to spray pesticides. The infestation collapsed from natural causes within five years. Estimates of the spruce mortality were on the order of 100,000 cords, of which 60% was recovered because the valuable wood is left untouched by the insect and can be harvested profitably. The budworm eats only the needles, which have no economic value apart from being part of the mechanism for survival and growth.[3]

By the late 1960s, Fenitrothion had been developed to replace DDT, whose adverse health and environmental effects were already noted.[3]

By winter 1975, medical staff at the Killam Hospital for Children in Halifax remarked that every child with a diagnosis of Reye's syndrome was a New Brunswicker, and later proved a link between the syndrome and the emulsifier used to apply the Fenitrothion. As a consequence of the furore surrounding the discovery of the Reye's syndrome link with pesticides, in 1976 the Nova Scotia Minister of Health, Allan Sullivan, cancelled a pesticide spraying programme that had only recently been approved by Cabinet.[6][7] Erik Sunblad, then president of Stora Koppenberg, who controlled the petitioner Nova Scotia Forest Industries, had threatened to shut down the works if his spraying programme met with official disapproval.[3]

Sunblad then went on to push another pesticide called Sevin, a trade name of carbaryl, which apparently required no emulsifier but was more expensive. It was at the time registered for use in Maine, but the Environmental Protection Agency stated that Sevin was "suspect right now", and by then several cases of Sevin poisoning had been seen already in Nova Scotia itself.[3]

Betimes in 1977, the now-deceased Lucretia J. Guerin,[8] president of a community organisation named "The Concerned Parents Group Inc." pursued FPL in the Provincial Court of New Brunswick. Hughes CJNB stated, upon appeal, that "Needless to say, the so-called 'spray programme' constitutes an extremely contentious issue due to conflicting concerns between those who believe the spray is necessary for the survival of the spruce and fir forests of the Province, and the economy based thereon, and those who are concerned over the effect of the spray upon the environment." Amongst other developments, a ministerial letter was required to save FPL from pursuit under the Pest Control Products Act.[9]

An outbreak of the insect was seen on the north shore of the St. Lawrence river in 2006. The outbreak zone has moved southwards and eastwards along with the prevailing wind.[10]

The Healthy Forest Partnership was created in 2014 by a wide variety of interests, both public and private, to better understand the spread of spruce budworm and to find a way to contain outbreaks of the insect, for which the group received $2.5M over four years from the Federal government. In 2018, they proposed a proactive intervention strategy, which employs aerial sprays of tebufenozide (a molting hormone, and agonist of the ecdysone receptor) and bacillus thuringiensis (soil-dwelling bacterium used as a biological pesticide), to the politicians.[10] In fact, they received $74.75 million over five years, to be made available on a 60-40 federal to provincial and industry cost-sharing basis. Quoth a Federal scientist: “We’re playing with mother nature to an extent here, but we’re very hopeful.”[11] The strategy was baptised the "Early Intervention Strategy" (EIS) by Jim Carr, who declared himself a keen supporter of "proactive, early intervention [pest control] strategies".[12] Only the Atlantic Canadian provinces were involved in the cost-sharing agreement.[13]

Controls

Budworm populations are usually regulated naturally by combinations of several natural factors such as insect parasites, vertebrate and invertebrate predators, and adverse weather conditions. During prolonged outbreaks when stands become heavily defoliated, starvation can be an important mortality factor in regulating populations.

This species is a favoured food of the Cape May warbler, which is therefore closely associated with its host plant, balsam fir. This bird, and the Tennessee and bay-breasted warblers, which also have a preference for budworm, lay more eggs and are more numerous in years of budworm abundance.

Natural enemies are probably responsible for considerable mortality when budworm populations are low, but seldom have a regulating influence when populations are in epidemic proportions.

Chemical insecticides such as malathion, carbaryl, and acephate can substantially reduce budworm. Microbial insecticides such as bacterium species Bacillus thuringiensis(Bt), a naturally occurring, host-specific pathogen that affects specific insect larvae based on the bacteria strain. Bt insecticides are often used in sensitive areas such as campgrounds or along rivers and streams, where it may not be desirable to use chemical insecticides with modes of action that affect fish and mammals.

The eastern spruce budworm is one of the most destructive insects of fir and spruce forests throughout Canada and the eastern United States.[14]

For biological methods, birds are important in controlling populations of the eastern spruce budworm below outbreak levels,[15] and the parasitic wasp Trichogramma minutum was investigated as a solution as well.[16]

Species

- Choristoneura adumbratanus (Walsingham, 1900)

- Choristoneura africana Razowski, 2002

- Choristoneura albaniana (Walker, 1863)

- Choristoneura argentifasciata Heppner, 1989

- Choristoneura biennis Freeman, 1967

- Choristoneura bracatana (Rebel, in Rebel & Rogenhofer, 1894)

- Choristoneura carnana (Barnes & Busck, 1920)

- Choristoneura chapana Razowski, 2008

- Choristoneura colyma Razowski, 2006

- Choristoneura conflictana (Walker, 1863)

- Choristoneura diversana (Hubner, [1814-1817])

- Choristoneura evanidana (Kennel, 1901)

- Choristoneura expansiva X.P.Wang & G.J.Yang, 2008

- Choristoneura ferrugininotata Obraztsov, 1968

- Choristoneura fractivittana (Clemens, 1865)

- Choristoneura freemani Razowski, 2008, western spruce budworm

- Choristoneura fumiferana (Clemens, 1865), eastern spruce budworm

- Choristoneura griseicoma (Meyrick, 1924)

- Choristoneura hebenstreitella (Muller, 1764), mountain-ash tortricid

- Choristoneura heliaspis (Meyrick, 1909)

- Choristoneura improvisana (Kuznetsov, 1973)

- Choristoneura irina Syachina & Budashkin, 2007

- Choristoneura jecorana (Kennel, 1899)

- Choristoneura jezoensis Yasuda & Suzuki, 1987

- Choristoneura lafauryana (Ragonot, 1875)

- Choristoneura lambertiana (Busck, 1915)

- Choristoneura longicellanus (Walsingham, 1900)

- Choristoneura luticostana (Christoph, 1888)

- Choristoneura metasequoiacola Liu, 1983

- Choristoneura murinana (Hubner, [1796-1799])

- Choristoneura neurophaea (Meyrick, 1932)

- Choristoneura obsoletana (Walker, 1863)

- Choristoneura occidentalis (Walsingham, 1891)

- Choristoneura orae Freeman, 1967

- Choristoneura palladinoi Razowski & Trematerra, 2010

- Choristoneura parallela (Robinson, 1869)

- Choristoneura pinus Freeman, 1953, jack pine budworm

- Choristoneura propensa Razowski, 1992

- Choristoneura psoricodes (Meyrick, 1911)

- Choristoneura quadratica Diakonoff, 1955

- Choristoneura retiniana (Walsingham, 1879)

- Choristoneura rosaceana (Harris, 1841)

- Choristoneura simonyi (Rebel, 1892)

- Choristoneura spaldingana Obraztsov, 1962

- Choristoneura thyrsifera Razowski, 1984

- Choristoneura zapulata (Robinson, 1869)

References

- ↑ MacLean, David A. (1984). "Effects of Spruce Budworm Outbreaks on the Productivity and Stability of Balsam Fir Forests". The Forestry Chronicle 60 (5): 273–279. doi:10.5558/tfc60273-5.

- ↑ Fellin, D. and J. Dewey (March 1992). Western Spruce Budworm Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 53, U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved on: September 14, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Mike Donovan: "The battle of the year". Atlantic Issues, February 1977 volume 1 number 1 pp 4-5

- ↑ MacDonald, D. R. (1968). "Management of Spruce Budworm Populations". The Forestry Chronicle 44 (3): 33–36. doi:10.5558/tfc44033-3.

- ↑ gnb.ca: "Energy and Resource Development - Forest Protection Limited"

- ↑ Kramer MS: Kids versus trees: Reye's syndrome and spraying for spruce budworm in New Brunswick J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Jun;62(6):578-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.002. Epub 2009 Apr 5.

- ↑ [Spitzer WO: Report of the New Brunswick Task Force on the Environment and Reye's syndrome] Clin Invest Med. 1982;5(2-3):203-14.

- ↑ mcadamsfh.com: "Richard Guerin 1927-2016"

- ↑ canlii.ca: "Forest Protection Ltd. v. Guerin", 1979-05-25: 1979 CanLII 2758 (NB QB); 25 NBR (2d) 513; 104 DLR (3d) 260

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Early intervention research is key for possible spruce budworm outbreak", 23 Feb 2018

- ↑ "Spruce budworm funding welcomed as push to keep species out of Nova Scotia continues", 27 Feb 2018

- ↑ "Government of Canada Supports Forestry by Tackling the Spruce Budworm Pest", 29 Mar 2018

- ↑ nrcan.gc.ca: "Tackling the Spruce Budworm Pest", 28 Mar 2018

- ↑ (in en) Out Of Print : Biosystematic Studies of Conifer-Feeding Choristoneura (Lepidoptera Tortricidae) in the Western United States : Edited by Jerry A. Powell - University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/op.php?isbn=9780520097964. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ↑ Crawford, Hewlette S.; Jennings, Daniel T. (1989). "Predation by Birds on Spruce Budworm Choristoneura Fumiferana: Functional, Numerical, and Total Responses". Ecology 70 (1): 152–163. doi:10.2307/1938422.

- ↑ Smith, S. M.; Hubbes, M.; Carrow, J. R. (1986). "Factors affecting inundative releases of Trichogramma minutum Ril. Against the Spruce Budworm". Journal of Applied Entomology 101 (1–5): 29–39. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0418.1986.tb00830.x.

Bibliography

- Brown, J.W., 2005: World Catalogue of Insects volume 5 Tortricidae.

- Ginzburg, L.R.; Taneyhill, D.E. (1994). "Population cycles of forest Lepidoptera: a maternal effect hypothesis". Journal of Animal Ecology 63 (1): 79–92. doi:10.2307/5585. http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/ee/ginzburglab/Population%20Cycles%20of%20Forest%20Lepidoptera%20-%20Ginzburg%20and%20Taneyhill,%201994.pdf.

- Hudak, J. (1991). "Integrated pest management and the eastern spruce budworm". Forest Ecology and Management 39: 313. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(91)90188-2.

- Kawabe, A., 1965: A revision of the genus Archips from Japan. Tyô to Ga 16 (1/2): 13-40. Abstract and Full article: [1].

- Patrick M. A. James; Louis‐Etienne Robert; B. Mike Wotton; David L. Martell; Richard A. Fleming (2017). "Lagged cumulative spruce budworm defoliation affects the risk of fire ignition in Ontario, Canada". Ecological Applications 27 (2): 532–544. doi:10.1002/eap.1463. PMID 27809401.

- Lederer, 1859, Wien. ent. Monatschr. 3: 426.

- Liu Y.-q., 1983: A new species of Choristoneura injurious to Metasequoia in Hubei province (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Entomotaxonomia 5 (4): 289-291. Full article: [2].

- William J. Mattson; Gary A. Simmons; John A. Witter (1988), Dynamics of Forest Insect Populations, Dynamics of Forest Insect Populations, Springer, pp. 309–330, doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0789-9_16, ISBN 978-1-4899-0791-2

- Neilson, M.M. (1963). "Disease and the spruce budworm". Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 95 (31): 272–287. doi:10.4039/entm9531272-1.

- Nedoshivina, S.V., 2007: On the type specimens of the Tortricidae described by Eduard Friedrich Eversmann from the Volgo-Ural Region. Nota Lepidopterologica, 30 (1): 93-114. Full article: [3].

- Julia Rauchfuss; Susy Svatek Ziegler (2011). "The Geography of Spruce Budworm in Eastern North America". Geography Compass 5 (8): 564–580. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00441.x.

- Razowski, J, 2008: Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) from South Africa. 6: Choristoneura Hübner and Procrica Diakonoff. Polish Journal of Entomology 77 (3): 245-254. [4].

- Razowski, J. & M. Krüger, 2013: An illustrated catalogue of the specimens of Tortricidae in the Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Shilap Revista de Lepidopterologia 41 (162): 213-240.

- Razowski, J. & P. Trematerra, 2010: Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) from Ethiopia Journal of Entomological and Acarological Research Serie II, 42 (2): 47-79. Abstract: [5].

- T. Royama (1984). "Population Dynamics of the Spruce Budworm Choristoneura Fumiferana". Ecological Monographs 54 (4): 429–462. doi:10.2307/1942595. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/cbb0541edd08791bbd853227a629df4e2ad2be76.

- Daniel T Jennings; Hewlette S Crawford, Jr (1985). Spruce Budworms Handbook: Predators of the Spruce Budworm. Agriculture Handbook. USDA. https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/CAT86864305/PDF.

- Martha H. Brookes; Robert W. Campbell; J. J. Colbert; Russel G. Mitchell; R. W. Stark (1987). Western Spruce Budworm. Technical Bulletin No. 1694; Canada/United States Spruce Budworms Program-West. USDA. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1318&context=barkbeetles.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spruce budworm. |

Wikidata ☰ Q1758763 entry