Biology:Tchoiria

| Tchoiria | |

|---|---|

| |

| T. klauseni skeleton at Dinosaurios del desierto de Gobi exhibition in Chile | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Choristodera |

| Suborder: | †Neochoristodera |

| Genus: | †Tchoiria Efimov, 1975 |

| Species | |

| |

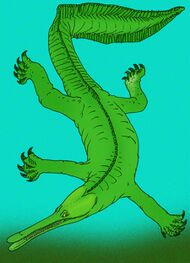

Tchoiria (/ˈtʃɔɪriə/) is a genus of neochoristoderan reptile from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia. The name Tchoiria comes from the city of Choir which is nearby to where the holotype was found.[1] Tchoiria is thought to have a similar diet to another neochoristoderan reptile, Champsosaurus, due to morphology of the skull. It would hunt in freshwater environments, like the living gharials, where it would prey on many different types of fish and turtles.[2][3]

History of research

Tchoiria remains were first recovered as a part of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Expeditions which took place in the Gobi Desert. They were described by Mikhail B. Efimov in 1975; basing his description on a partial cranium and some parts of the postaxial skeleton found at the Hühteeg Formation. He would make the type species T. namsari.[1][4] Efimov would name two other Tchoiria species in the latter 20th century, T. magnus in 1979 and T. egloni in 1983. Both taxa were based on postcranial fossils that were also found in the Hühteeg Formation. These would later be redescribed as new members of neochoristodera by Efimov.[5][4] The second valid species of Tchoiria would be named in 2005 by Danial T. Ksepka. T. klauseni would be based on a partial skull and some postcranial material found at the Two Volcanoes locality of southern Mongolia.[6] Efimov would place Tchoiria in the order choristodera in his original description.[1] Later it would also be placed in suborder neochoristodera in 2007 by Ryoko Matsumoto. Matsumoto would declare the suborder monophyletic in his paper on the choristodere Monjurosuchus.[7] Tchoiria was the first choristodere known from Asia and has been used in many morphological and environmental studies based on the order since its original description.[1][4]

There has been a total of four species of Tchoiria named, but as of 2023, only two are considered valid. T. magnus was moved to the genus Ikechosaurus in 1981 and T. egloni was moved to the new genus Irenosaurus in 1988.[4] These two taxa were moved due to morphological differences when compared to the T. namsari.

Description

Skull

The skull of Tchoiria is similar to other neochoristoderes in having a flared postorbital region, an elongated and narrow snout, and having small orbits. The skull is also very flattened like other members of neochoristodera. The nasals have also fused into a single element. The teeth of Tchoiria are conical in shape and decrease in size further back in the skull. They also curve medially and have vertical, parallel lines. The orbits have a raised rim surrounding them and are very rough in texture.[6] Like other diapsid reptiles, Tchoiria has two temporal fenestrae behind the orbit. The snout is shorter than the Champsosaurus but still longer than other choristoderes. Other skull traits include a shortened lower jaw symphysis, a broader and shorter rostrum, and the posterior displacement of mandibular articulation.[1][4]

T. namsari is the type species and is known from the Hühteeg Formation of Mongolia. The other species, T. klauseni is known from the Two Volcanoes locality of southern Mongolia. T. klauseni was separated from T. namsari by the number of teeth in both the maxilla and the dentary. T. namsari is known to have more teeth, 60 in the maxilla and 17 in the symphyseal portion of the dentary, while T. klausnei has a smaller number of them, 34 in the maxilla and 12 in the symphyseal portion of the dentary.[6]

Postcranial skeleton

A complete set of vertebrae for Tchoiria have not been fully preserved but specimens of each section have been described. The vertebrae have amphiplatyan-style centrum and a closed notochordal canal. The dorsal vertebrae have small processes below their respective postzygapophyses. These are similar to the processes seen in both Simeodosaurus and Ikechosaurus.[6][8] The caudal vertebrae have the unique trait of having a deep groove bordered by ventral flanges; a trait seen in choristoderes but not usually in neochoristoderes. The caudal vertebrae also have unfused hemal arches. Tchoiria had similar gastralia to other members of its suborber. The limbs of Tchoiria are very fragmentary. Parts of the shoulder girdle are preserved and shows that they would be long and narrow. Besides a single femur, the rest of the hindlimbs are unknown.[6]

Classification

Tchoiria has been placed in neochoristodera, which is a clade within choristodera. The group first appeared in the Early Cretaceous of Asia and were successful due to the absence of crocodiles. Later in the Cretaceous and the early Paleocene, neochoristoderans needed to become more specialized because of their shared ecosystem with a wide range of crocodiles.[9]

The phylogenic tree below comes from Dong et al. (2020) shows neochoristodera and their relationship to other members of choristodera.[10]

|

Cteniogenys sp. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoenvironment

The Khuren Dukh Formation has been sampled as containing mostly mudstone layers. This does not change till the upper parts of the formation, transitioning to shale and claystone layers.[11] This formation was first explored in the early 1970's as a part of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian expeditions and has been dated to Aptian in age by pollen and invertebrate fossils.[12] The scant plant fossils found nearby shows the environment to be a staple of the Cretaceous; a temperate and plant-covered ecosystem.[citation needed]

Tchoiria lived in a diverse ecosystem of other invertebrate and vertebrate taxa. The aquatic environment included but is not limited to mollusks, Ostracods, bony fish, turtles, some crocodiles, and Tchoiria itself. The terrestrial environment matched many other in the Early Cretaceous. Many dinosaurs including Psittacosaurus, Harpymimus, and some unidentified theropods. They coexisted with some pterosaurs and small lizards.[3] It would prey on fish and turtles mostly and would be hunted by a few crocodiles and theropod dinosaurs. Tchoiria would be a relatively uncommon animal in its ecosystem, but this could be due to a sampling bias with the locality.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Efimov, M.B. (1975). "Khampsozavrid iz Nizhnego Mela Mongolii". Iskopaemaya Fauna I Flora Mongolii. Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya, Trudy 2: 84–93.

- ↑ Evans, Susan E.; Hecht, Max K. (1993), Hecht, Max K.; MacIntyre, Ross J.; Clegg, Michael T., eds., "A History of an Extinct Reptilian Clade, the Choristodera: Longevity, Lazarus-Taxa, and the Fossil Record" (in en), Evolutionary Biology (Boston, MA: Springer US): pp. 323–338, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-2878-4_8, ISBN 978-1-4615-2878-4, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2878-4_8, retrieved 2023-03-02

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Masaki, Matsukawa. Early Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystems in East Asia based on food-web and energy-flow models. OCLC 1039765867. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1039765867.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 M. J. Benton (2003). The age of dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54582-X. OCLC 53710242. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53710242.

- ↑ "Tchoiria". https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=37789.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Kspeka, D.T.; Evans, S.E.; Norell, M.A. (2005). "A New Choristodere from the Cretaceous of Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (3468): 1. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2005)468<0001:ANCFTC>2.0.CO;2. https://bioone.org/journals/american-museum-novitates/volume-2005/issue-3468/0003-0082(2005)468%3c0001%3aANCFTC%3e2.0.CO%3b2/A-New-Choristodere-from-the-Cretaceous-of-Mongolia/10.1206/0003-0082(2005)468%3C0001:ANCFTC%3E2.0.CO;2.full.

- ↑ Ryoko, Matsumoto (2007). The choristoderan reptile Monjurosuchus from the Early Cretaceous of Japan. OCLC 999165005. http://worldcat.org/oclc/999165005.

- ↑ Evans, Susan E.; Manabe, Makoto (1999). "A choristoderan reptile from the Lower Cretaceous of Japan". Special Papers in Palaeontology.

- ↑ Matsumoto, R.; Evans, S. E. (2010). "Choristoderes and the freshwater assemblages of Laurasia". Journal of Iberian Geology 36 (2): 253–274. doi:10.5209/rev_JIGE.2010.v36.n2.11. ISSN 1698-6180. http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/JIGE/article/view/JIGE1010220253A.

- ↑ Dong, Liping; Matsumoto, Ryoko; Kusuhashi, Nao; Wang, Yuanqing; Wang, Yuan; Evans, Susan E. (2020-08-02). "A new choristodere (Reptilia: Choristodera) from an Aptian–Albian coal deposit in China". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 18 (15): 1223–1242. doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1749147. ISSN 1477-2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2020.1749147.

- ↑ Nichols, Douglas J.; Matsukawa, Masaki; Ito, Makoto (April 2006). "Palynology and age of some Cretaceous nonmarine deposits in Mongolia and China". Cretaceous Research 27 (2): 241–251. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.11.004. ISSN 0195-6671. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2005.11.004.

- ↑ Hicks, J.F.; Brinkman, D.L.; Nichols, D.J.; Watabe, M. (December 1999). "Paleomagnetic and palynologic analyses of Albian to Santonian strata at Bayn Shireh, Burkhant, and Khuren Dukh, eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia". Cretaceous Research 20 (6): 829–850. doi:10.1006/cres.1999.0188. ISSN 0195-6671. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/cres.1999.0188.

Wikidata ☰ Q587956 entry

|