Biology:Champsosaurus

| Champsosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| C. natator skeleton, Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Choristodera |

| Suborder: | †Neochoristodera |

| Genus: | †Champsosaurus Cope, 1877 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Champsosaurus is an extinct genus of crocodile-like choristodere reptile, known from the Late Cretaceous and early Paleogene periods of North America and Europe (Campanian–Paleocene). The name Champsosaurus is thought to come from champsai, (χαμψαι) said in an Ancient Greek source to be an Egyptian word for "crocodiles", and sauros, (σαύρος) Greek for "lizard". The morphology of Champsosaurus resembles that of gharials, with a long, elongated snout. It was native to freshwater environments where it likely preyed on fish, similar to living gharials.

History of research

Champsosaurus was the first member of the Choristodera to be described. Champsosaurus was named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1876, from isolated vertebrae found in Late Cretaceous strata of the Judith River Formation on the banks of the Judith River in Fergus County, Montana. Cope designated C. annectens as the type species rather than the first named C. profundus due to the larger number of vertebrae he attributed to the species. C. annectens was based on 9 isolated vertebral centra (AMNH FR 5696) that were not figured in the paper of which two are now lost.[1][2] Cope named several other species between 1876 and 1882, also based on isolated vertebrae. Barnum Brown in 1905 described the first complete remains of Champsosaurus, and noted that one of the species attributed to Champsosaurus by Cope in 1876, C. vaccinsulensis actually represented indeterminate plesiosaur remains, and that the vertebrae that Cope used to diagnose his species of Champsosaurus were heavily eroded and the diagnostic features varied substantially along the spinal column, and were not diagnostic to species level, including the remains that Cope attributed to the type species C. annectens.[3] The conclusion that C. annectens was undiagnostic was supported by William Parks in 1933.[4]

Brown in 1905 named two species of Champsosaurus. One was C. ambulator, named from the specimen AMNH 983, a fragmentary skeleton with a partial skull found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana. The other was C. laramiensis, named from AMNH 982, a nearly complete skeleton and skull, also found in the Hell Creek Formation.[3] Parks in 1927 named C. albertensis from ROM 806, a partial skeleton lacking the skull, found in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation in Alberta, Canada.[5] Parks in 1933 named the species C. natator from an incomplete skeleton with a fragmentary skull (TMP 81.47.1) found in the Belly River Group in the Red Deer River valley in Alberta.[4] In 1979, Denise Sigogneau-Russell named the species C. dolloi from remains found in the Paleocene of Belgium.[6] In 1972, Bruce Erickson named the species C. gigas from SMM P71.2.1, a partial skeleton and skull found in the Sentinel Butte Formation, Golden Valley County, North Dakota.[7] Erickson subsequently in 1981 named the species C. tenuis from SMM P79.14.1, a partial skeleton and skull found in the Bullion Creek Formation, North Dakota. In 1998 K. Q. Gao and Richard Carr Fox described the species C. lindoei from UALVP 931, a nearly complete skeleton with skull and jaws from the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta. The publication also thoroughly reviewed Champsosaurus, rediagnosing most species except for C. ambulator and C. laramiensis.[8]

Fossils of Champsosaurus have been found in North America (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Montana, New Mexico, Texas ,[9] Colorado, and Wyoming) and Europe (Belgium and France ), dating from the Upper Cretaceous to the late Paleocene. Remains tentatively referred to Champsosaurus are known from the high Canadian Arctic, dating to the Coniacian–Turonian, a time of extreme warmth.[10]

Taxonomy

Sixteen species of Champsosaurus have been named, of which seven are presently considered valid.[2] The type species Champsosaurus annectens Cope, 1876 is considered to be dubious.[2] The only named European species C. dolloi Sigogneau-Russell 1979 was considered to be too fragmentary to warrant a new species by Gao and Fox in 1998.[2]

| Species | Author | Year | Status | Temporal range | Location | Formations | Notes & description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Champsosaurus ambulator | Brown | 1905 | Valid | Maastrichtian-Paleocene | United States (Montana) | Hell Creek, Tullock | Distinguished from C. laramiensis by having robust limbs and limb girdles[2] |

| Champsosaurus laramiensis | Brown | 1905 | Maastrichtian-Paleocene | United States (Montana, New Mexico) Canada (Saskatchewan) | Hell Creek, Frenchman, Tullock, Puerco, Torrejonian | Synonyms C. australis Cope, 1881, C. puercensis Cope, 1881, C. saponensis Cope, 1881 distinguished from C. ambulator by having gracile limbs and long bones.[2] | |

| Champsosaurus albertensis | Parks | 1927 | Campanian-Maastrichtian | Canada (Alberta) | Horseshoe Canyon | Distinguished from other species of Champsosaurus based on proportionately short epipodials, though Gao and Fox (1998) suggest that this may not be taxonomically significant.[2] | |

| Champsosaurus natator | Parks | 1933 | middle-late Campanian | Canada (Alberta) | Dinosaur Park | Relatively large species (~ 2 metres in length) syn. C. profundus Cope, 1876, C. brevicollis Cope, 1876, C. inelegans Parks, 1933, C. inflatus Parks, 1933 distinguished by " (1) a more robust skull than the contemporaneous C. lindoei; (2) laterally swollen lower temporal bar; (3) lower temporal fenestra expanded mediolaterally; (4) expansion of the postfrontal separating the postorbitals from the frontals"[2] | |

| Champsosaurus gigas | Erickson | 1972 | Paleocene | United States (North Dakota) Canada (Saskatchewan) | Sentinel Butte, Ravenscrag | Largest species of the genus, reaching a length of approximately 3 metres. Distinguished by "(1) parietal table strongly projecting laterally at anterior margin of superior temporal fenestra; (2) posterior part of parietal table narrower than in other species of comparable size; (3) postorbital extending anteromedially to meet frontal and parietal, preventing postfrontal-parietal contact"[2] | |

| Champsosaurus tenuis | Erickson | 1981 | Paleocene | United States (North Dakota) | Bullion Creek | Distinguished by "(1) An extremely long and slender snout; (2) postcranial skeleton with narrow shoulder girdle; (3) clavicles short and deeply concave anteriorly; (4) limbs reduced in length"[2] | |

| Champsosaurus lindoei | Gao and Fox | 1998 | middle-late Campanian | Canada (Alberta), United States (Montana) | Dinosaur Park, Two Medicine.[11] | Relatively small member of the genus characterised by "(1) snout significantly more slender in proportion to the skull size, and the bulla on the snout is proportionately larger; (2) the pterygoid flange is weekly developed with reduced number of teeth; (3) inferior temporal arch is nearly straight, and is not swollen laterally; (4) subtemporal fenestra is rectangular, not oval".[2] |

Description

Most species grew to about 1.50 m (5 ft) long,[12] though Champsosaurus gigas, the largest species, reached 3–3.5 m (10–12 ft) in length.[13][14][12]

Anatomy

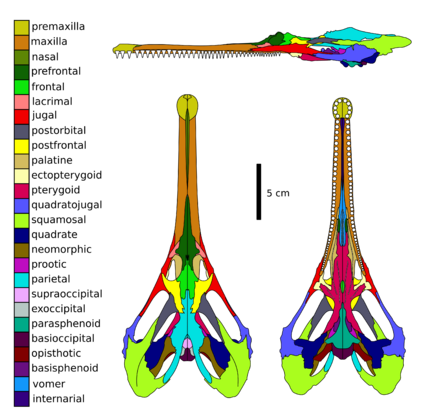

The skull of Champsosaurus is dorsoventrally flattened, while the temporal arches are expanded posteriorly (towards the back of the skull) and laterally (away from the midline), giving the skull a heart shaped appearance when viewed from above. The snout is greatly elongated and gharial-like, making up around half the length of the skull, and at least four times as long as it is wide,[15] with the opening of the nostrils at the end of the snout. The openings of the ears are located on the underside of the skull.[16] The body is flat and streamlined, with heavy gastralia (rib-like bones situated in the belly).[15] Compared to other choristoderes, the lacrimal bone is reduced in size to a small triangle, the postorbital bone does not form part of the orbit (eye socket), there is no contact between the premaxilla and the vomer bones, an internarial bone is present, the choanae are located posteriorly in correlation to the elongation of the vomer, the interpterygoid vacuity is small and completely enclosed by the pterygoid bones and located near the posterior margin of the suborbital fenestra, the shape of the suborbital fenestra is shortened and kidney like, the articulation between the pterygoid and the parasphenoid is fused, the joint between the skull and the lower jaws is anterior to level of the occipital condyles, the neomorphic bone forms most of the border of the posttemporal fenestra, the paroccipital process is strongly deflected downwards, the basal tubera of the basisphenoid are wing-like in shape and expanded backwards and downwards, the mandibular symphysis (connection of the two halves of the lower jaw) is elongated to over half the length of the tooth row, and the splenial bone strongly intervenes in the mandibular symphysis.[8]

Internal cranial anatomy

The braincase of Champsosaurus is poorly ossified at the front of the skull (anterior), but is well ossified in the rear (posterior) similar to other diapsids. The cranial endocast (space occupied by the brain in the cranial vault) is similar to that of basal archosauromorphs, being proportionally narrow in both dorsoventral and lateral axes, with an enlarged pineal body and olfactory bulbs. The optic lobes and flocculi are small in size, indicating only average vision ability at best. The olfactory chambers of the nasal passages and olfactory stalks of the braincase are reasonably large, indicating that Champsosaurus probably had good olfactory capabilities (sense of smell). The nasal passages lack bony turbinates. The semicircular canals are most similar to those of other aquatic reptiles. The expansion of the sacculus indicates that Champsosaurus likely had an increased sensitivity to low frequency sounds and vibrations. The absence of an otic notch indicates that Champsosaurus lacked a tympanum, and probably had a poor ability to detect airborne sounds.[17]

Teeth

Champsosaurus, like many of its fellow neochoristoderes, features teeth with striated enamel of the tooth crown with enamel infolding at the base. Anterior teeth are typically sharper and more slender than posterior teeth. Like other choristoderes, Champsosaurus possessed palatal teeth (teeth present on the bones of the roof of the mouth), with longitudinal rows present on the pterygoid, palatine and vomer, alongside a small row on the flange of the pterygoid. The palatine teeth of Champsosaurus are located on raised platforms of bone, though the wideness of the platforms, the sharpness and orientation of teeth vary between species. The orientation of the teeth varies in the jaw, with the posterior teeth being orientated backward. The palatal teeth, likely in combination with a fleshy tongue probably aided in gripping and swallowing prey.[18]

Skin

Skin impressions of Champsosaurus have been reported. They consist of small (0.6-0.1 mm) pustulate and rhomboid scales, with the largest scales being located on the lateral sides of the body, decreasing in size dorsally, no osteoderms were present.[15]

Classification

Champsosaurus belongs to the Neochoristodera, a clade within Choristodera, the members of which are characterised by elongated snouts and expanded temporal arches. The group first appeared during the Early Cretaceous in Asia, and are suggested to have evolved in the regional absence of aquatic crocodyliformes.[19] While Neochoristodera is a well supported grouping, the relationships of the members of the group to each other are uncertain, with the clade having been recovered as a polytomy in recent analyses.[20]

Phylogeny of Choristodera after Dong and colleagues (2020).[20]

| Choristodera |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Champsosaurus is thought to have been highly specialised for aquatic life.[15] Erickson 1985 suggested that the expanded temporal arches, which likely anchored powerful jaw muscles, and elongated snout allowed Champsosaurus to prey on fish akin to modern gharials, with these adaptions allowing rapid movement of the head and jaws for prey capture.[15] A study in 2021 found that the middle and posterior neck vertebrae of Champsosaurus were adapted for lateral movement, and that Champsosaurus may have fed by laterally sweeping its head, using its slender jaws to grab individual fish from shoals, akin to how modern gharials feed. The mechanism of head movement is different from that of gharials, where the lateral movement occurs at the head-neck joint. It is unlikely that Champsosaurus fed by inertial feeding (where the prey is temporarily let go and the head moved forwards in order to force the prey deeper into the throat), but that the prey was moved down the throat by the tongue in combination with the palatal dentition.[21] Erickston 1985 proposed that the position of the nostrils at the front of the snout allowed Champsosaurus to spend large amounts of time at the bottom of water bodies, with the head being angled upwards to allow the snout to act like a snorkel when the animal needed to breathe.[15] However, later studies suggested that the neck vertebrae of Champsosaurus only had a limited ability to flex upwards.[21] Champsosaurus co-existed with similarly sized aquatic crocodilians and at some Paleocene localities with fellow neochoristodere Simoedosaurus, though in assemblages where Champsosaurus occurs longirostrine (long snouted) gharial-like crocodilians are absent, suggesting that there was niche differentiation.[19] Previously, two species of Champsosaurus were identified from the Tullock Formation in Montana. However, these differences are now thought to be sexually dimorphic, with presumed females possessing robust limb bones. Non-deformation related fusion of the sacral vertebrae is also observed in specimens with robust limb bones. These are hypothesised to be related to breeding behaviour, with the more robust limb bones and fused sacrals of the females allowing them to move themselves onto land to lay eggs.[22][23]

See also

- Tullock Formation

- Hell Creek Formation

- Paleontology in Montana

References

- ↑ "On some extinct reptiles and Batrachia from the Judith River and Fox Hills beds of Montana". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1876: 340–359. 1876.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Dudgeon, Thomas William (2019). The internal cranial anatomy of Champsosaurus lindoei and its functional implications (PDF). Earth Sciences (M.Sci.). Ottawa, Ontario: Carleton University.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 B. Brown. 1905. The osteology of Champsosaurus Cope. American Museum of Natural History, Memoirs 9:1–264

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 W. A. Parks. 1933. New species of Champsosaurus from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, Canada. Transactions of Royal Society of Canada 27:121–137

- ↑ W. A. Parks. 1927. Champsosaurus albertensis, a new species of rhynchocephalian from the Edmonton Formation of Alberta. University of Toronto Studies of Geological Survey 25:1–48

- ↑ Sigogneau-Russell D. 1979. Les champsosaures Européens: mise au point sur le champsosaure d'erquelinnes (landenien inferieur, Belgique). Annales de Paliontologit (Vertibris) 65: 7–62.

- ↑ B. R. Erickson. 1972. The lepidosaurian reptile Champsosaurus in North America. The Science Museum of Minnesota, Monograph (Paleontology) 1:1–91

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gao, Keqin; Fox, Richard C. (December 1998). "New choristoderes (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Upper Cretaceous and Palaeocene, Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada, and phylogenetic relationships of Choristodera" (in en). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 124 (4): 303–353. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb00580.x.

- ↑ Lehman, Thomas M.; Barnes, Ken (2010). "Champsosaurus (Diapsida: Choristodera) from the Paleocene of west Texas: paleoclimatic implications". Journal of Paleontology 84 (2): 341–345. doi:10.1666/09-111R.1.

- ↑ Vandermark, Deborah; Tarduno, John A.; Brinkman, Donald B. (May 2007). "A fossil champsosaur population from the high Arctic: Implications for Late Cretaceous paleotemperatures". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 248 (1–2): 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.11.008. ISSN 0031-0182. Bibcode: 2007PPP...248...49V. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.11.008.

- ↑ Dudgeon, Thomas W; Mallon, Jordan C; Evans, David C (2023-08-17). "The first report of Champsosaurus lindoei (Choristodera: Champsosauridae) from the Campanian of the United States: anatomical, phylogenetic, and palaeoecological significance" (in en). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad087. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 D.Lambert, D.Naish and E.Wyse 2001, "Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and prehistoric life", p. 77, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London. ISBN 0-7513-0955-9

- ↑ Hoganson, J.W.; J. Campbell (1995). "Restoration and display of a crocodilie-like Champsosaurus gigas skeleton at the North Dakota Heritage Center". NDGS Newsletter 22 (3): 8–10. https://www.dmr.nd.gov/dmr/sites/www/files/documents/paleontology/pdfs/articles-and-publications/restorechampus.pdf.

- ↑ "Champsosaurus gigas". Department of Mineral Resources, North Dakota. https://www.dmr.nd.gov/ndfossil/poster/PDF/Champosaurus%20gigas.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 "Aspects of some anatomical structures of Champsosaurus (Reptilia: Eosuchia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 5 (2): 111–127. June 1985. doi:10.1080/02724634.1985.10011849.

- ↑ Dudgeon, Thomas W.; Maddin, Hillary C.; Evans, David C.; Mallon, Jordan C. (April 2020). "Computed tomography analysis of the cranium of Champsosaurus lindoei and implications for the choristoderan neomorphic ossification" (in en). Journal of Anatomy 236 (4): 630–659. doi:10.1111/joa.13134. ISSN 0021-8782. PMID 31905243.

- ↑ Dudgeon, Thomas W.; Maddin, Hillary C.; Evans, David C.; Mallon, Jordan C. (2020-04-28). "The internal cranial anatomy of Champsosaurus (Choristodera: Champsosauridae): Implications for neurosensory function" (in en). Scientific Reports 10 (1): 7122. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-63956-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 32346021. Bibcode: 2020NatSR..10.7122D.

- ↑ "Morphology and function of the palatal dentition in Choristodera". Journal of Anatomy 228 (3): 414–29. March 2016. doi:10.1111/joa.12414. PMID 26573112.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Choristoderes and the freshwater assemblages of Laurasia". Journal of Iberian Geology 36 (2): 253–274. 2010. doi:10.5209/rev_jige.2010.v36.n2.11.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Dong, Liping; Matsumoto, Ryoko; Kusuhashi, Nao; Wang, Yuanqing; Wang, Yuan; Evans, Susan E. (2020-08-02). "A new choristodere (Reptilia: Choristodera) from an Aptian–Albian coal deposit in China" (in en). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 18 (15): 1223–1242. doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1749147. ISSN 1477-2019. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14772019.2020.1749147.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Matsumoto, Ryoko; Fujiwara, Shin-ichi; Evans, Susan E. (2021). "Feeding behaviour and functional morphology of the neck in the long-snouted aquatic fossil reptile Champsosaurus (Reptilia: Diapsida) in comparison with the modern crocodilian Gavialis gangeticus" (in en). Journal of Anatomy 240 (5): 893–913. doi:10.1111/joa.13600. ISSN 1469-7580. PMID 34865223.

- ↑ Katsura, Yoshiro (2004). "Sexual dimorphism in Champsosaurus (Diapsida, Choristodera)". Lethaia 37 (3): 245–253. doi:10.1080/00241160410006447. ISSN 0024-1164.

- ↑ Katsura, Yoshiro (2007). "Fusion of sacrals and anatomy in Champsosaurus (Diapsida, Choristodera)". Historical Biology 19 (3): 263–271. doi:10.1080/08912960701374659.

Wikidata ☰ Q860015 entry

|