Biology:Thylacoleo carnifex

| Thylacoleo carnifex | |

|---|---|

| File:Journal.pone.0208020.g011.tif | |

| Skeleton, and outline based on extant marsupial musculature | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | †Thylacoleonidae |

| Genus: | †Thylacoleo |

| Species: | †T. carnifex

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Thylacoleo carnifex Owen, 1859

| |

Thylacoleo carnifex, also known as the "marsupial lion", is an extinct species of carnivorous marsupial mammal that lived in Australia from the early to the late Pleistocene (1.6 million–35 thousand years ago).[1][2] Unlike the Thylacine, it is a member of the largely herbivorous Vombatiformes, related to the koala and wombat.

Description

A species of Thylacoleo, it is the largest meat-eating mammal known to have ever existed in Australia, and one of the larger metatherian carnivores of the world (comparable to Thylacosmilus and Borhyaena species, but smaller than Proborhyaenidae). Individuals ranged up to around 75 cm (30 in) high at the shoulder and about 150 cm (59 in) from head to tail. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show they averaged 101 to 130 kg (223 to 287 lb) in weight, although individuals as large as 124–160 kg (273–353 lb) might not have been uncommon, and the largest weight was of 128–164 kg (282–362 lb).[3] This would make it comparable to female lions and female tigers in general size.

The animal was extremely robust with powerfully built jaws and very strong forelimbs. It possessed retractable claws, a unique trait among marsupials. This would have allowed the claws to remain sharp by protecting them from being worn down on hard surfaces. The claws were well-suited to securing prey and for climbing trees. The first digits ("thumbs") on each hand were semi-opposable and bore an enlarged claw. Palaeontologists believe this would have been used to grapple its intended prey, as well as providing it with a sure footing on tree trunks and branches. The hind feet had four functional toes, the first digit being much reduced in size, but possessing a roughened pad similar to that of possums, which may have assisted with climbing. The discovery in 2005 of a specimen which included complete hind feet provided evidence that the marsupial lion exhibited syndactyly (fused second and third toes) like other diprotodonts.[4]

The species hindquarters were also well-developed, although to a lesser extent than the front of the animal. Remains of the animal show it had a relatively thick and strong tail and the vertebrae possessed chevrons on their undersides where the tail would have contacted the ground. These would have served to protect critical elements such as nerves and blood vessels if the animal used its tail to support itself when on its hind legs, much like present day kangaroos do. Taking this stance would free up its fore limbs to tackle or slash at its intended victim.[5] The discovery of complete skeletons preserving both the tail and clavicles (collarbones) in Australia's Komatsu Cave in the town of Naracoorte and Flight Star Cave in the Nullarbor Plain, indicate the marsupial lion had a thick, stiff tail that comprised half the spinal column's length. The tail may have been used in novel behaviors not seen in other marsupials, and was probably held aloft continuously. The discovery of the clavicle indicates that the marsupial lion may have had a similar type of locomotion to the modern Tasmanian devil.[6]

Evolutionary relationships

The ancestors of thylacoleonids are believed to have been herbivores, something unusual for carnivores. Cranial features and arboreal characteristics suggest that thylacoleonids share a common ancestor with wombats.[7] While other continents were sharing many of their predators amongst themselves, as they were connected by land, Australia's isolation caused many of its normally docile herbivorous species to turn carnivorous.[8] Possum-like features were once thought to indicate that the marsupial lion's evolutionary path was from a phalangeriform ancestor, however, scientists agree that more prominent features suggest a vombatiform ancestry.[9] However, the recently discovered Microleo is a possum-like animal.[10]

Dentition

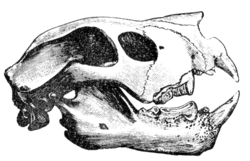

The marsupial lion was a highly specialised carnivore, as is reflected in its dentition. Like other diprotodonts, it possessed enlarged incisors on both the upper (maxillae) and lower (mandibles) jaws. These teeth (the lower in particular) were shaped much more like the pointed canine teeth of animals such as dogs and cats than those of kangaroos. The most unusual feature of the creature's dentition were the huge, blade-like carnassial premolars on either side of its jaws. The top and bottom carnassials worked together like shears and would have been very effective at slicing off chunks of flesh from carcasses and cutting through bone.

The jaw muscle of the marsupial lion was exceptionally large for its size, giving it an extremely powerful bite. Biometric calculations show, considering size, it had the strongest bite of any known mammal, living or extinct; a 101 kg (223 lb) individual would have had a bite comparable to that of a 250 kg (550 lb) African lion. A comparative study of bite force in relation to the body mass of fossil and modern species, found the greatest relative force exerted by the jaws would have been this species and Priscileo roskellyae.[11] Using 3D modeling based on X-ray computed tomography scans, marsupial lions were found to be unable to use the prolonged, suffocating bite typical of living big cats. They instead had an extremely efficient and unique bite; the incisors would have been used to stab at and pierce the flesh of their prey while the more specialised carnassials crushed the windpipe, severed the spinal cord, and lacerated the major blood vessels such as the carotid artery and jugular vein. Compared to an African lion which may take 15 minutes to kill a large catch, the marsupial lion could kill a large animal in less than a minute. The skull was so specialized for big game that it was very inefficient at catching smaller animals, which possibly contributed to its extinction.[12][13]

Behaviour

The marsupial lion's limb proportions and muscle mass distribution indicate that, although it was a powerful animal, it was not a particularly fast runner. Paleontologists conjecture that it was an ambush predator, either sneaking up and then leaping upon its prey, or dropping down on it from overhanging tree branches. This is consistent with the depictions of the animal as striped: camouflage of that kind is needed for stalking and hiding in a largely forested habitat (like tigers) rather than chasing across open spaces (like lions).[14] Trace fossils in the form of claw marks and bones from caves in Western Australia analyzed by Gavin Prideaux et al. indicate marsupial lions could also climb rock faces, and likely reared their young in such caves as a way of protecting them from potential predators.[15] It is thought to have hunted large animals such as the enormous Diprotodon and giant browsing kangaroos like Sthenurus and Procoptodon, and competed with other predatory animals such as the giant monitor lizard, Megalania, and terrestrial crocodiles such as Quinkana. The marsupial lion may have cached kills in trees in a manner similar to the modern leopard.[16] Like many predators, it was probably also an opportunistic scavenger, feeding on carrion and driving off less powerful predators from their kills. It also may have shared behaviours exhibited by recent diprotodont marsupials such as kangaroos, like digging shallow holes under trees to reduce body temperature during the day.[17]

CT scans of a well-preserved skull have allowed scientists to study internal structures and create a brain endocast showing the surface features of the animal's brain. The parietal lobes, visual cortex, and olfactory bulbs of the cerebrum were enlarged, indicating the marsupial lion had good senses of hearing, sight, and smell, as might be expected of an active predator. Also, a pair of blind canals within the nasal cavity were probably associated with detecting pheromones as in the Tasmanian devil. This indicates it most likely had seasonal mating habits and would "sniff out" a mate when in season.[18]

Palaeoecology

Numerous fossil discoveries indicate the marsupial lion was distributed across much of the Australia n continent. A large proportion of its environment would have been similar to the southern third of Australia today, semiarid, open scrub and woodland punctuated by waterholes and water courses.[citation needed]

It would have coexisted with many of the so-called Australian megafauna such as Diprotodon, giant kangaroos, and Megalania, as well as giant wallabies like Protemnodon, the giant wombat Phascolonus, the giant snake Wonambi, and the thunderbird Genyornis.[18]

Australia's Pleistocene megafauna would have been the prey for the agile T. carnifex, who was especially adapted for hunting large animals, but was not particularly suited to catching smaller prey. The relatively quick reduction in the numbers of its primary food source around 40,000 to 50,000 years ago probably led to the decline and eventual extinction of the marsupial lion. The arrival of humans in Australia and the use of fire-stick farming precipitated their decline.[19] The extinction of T. carnifex makes Australia unique from the other continents because no substantial, apex mammalian predators have replaced the marsupial lions after their disappearance.[20]

Classification

The marsupial lion is classified in the order Diprotodontia along with many other well-known marsupials such as kangaroos, possums, and the koala. It is further classified in its own family, the Thylacoleonidae, of which three genera and 11 species are recognised, all extinct. The term marsupial lion (lower case) is often applied to other members of this family. Distinct possum-like characteristics led Thylacoleo to be regarded as members of Phalangeroidea for a few decades. Though a few authors continued to hint at phalangeroid affinities for thylacoleonids as recently as the 1990s, cranial and other characters have generally led to their inclusion within vombatiformes, and as stem-members of the wombat lineage.[7] Marsupial lions and other ecologically and morphologically diverse vombatiforms were once represented by over 60 species of carnivorous, herbivorous, terrestrial and arboreal forms ranging in size from 3 kg to 2.5 tonnes. Only two families represented by four herbivorous species (koalas and three species of wombat) have survived into modern times and are considered the marsupial lion's closest living relatives.[21]

Fossils

Fossils of the marsupial lion have been found at several sites in Australia since the mid-19th century. A complete articulated skeleton was discovered in limestone caves under the Nullarbor Plain in 2002. The ends of the limb bones were not fully fused, indicating the animal was not full-grown.

Unlike most fossils, these bones were not mineralised and had been preserved in this state for about 500,000 years by the low humidity and cool temperature of the cave. The partial remains of 10 other individuals were found in this or nearby caves, along with hundreds of other specimens of other animals.[22]

The animals apparently fell to their deaths tens of metres below, through narrow openings in the roof of the caves known as sinkholes. The caves and sinkholes were formed by groundwater slowly dissolving and eroding the limestone forming the bed of the plain (once a shallow sea).[2]

Possible marsupial lion trace fossils have been found in a lake bed in south-western Victoria, along with trackways of a vombatid, the diprotodontid Diprotodon optatum, and a macropodid. The footprints were imprinted over a short period of time which may suggest an association between the marsupial lion and the other taxa present.[23] In addition, marsupial lion body fossils have been found in the same area and are dated around the same time as its trace fossils, a coincidence that is extremely rare and that may aid in a more complete assessment of the biodiversity in Australia during the Pleistocene epoch. Other fossils found at the site have bite marks that were presumably caused by the marsupial lion.[24]

Extinction

As with most of the Australian megafauna, the events leading to the extinction of T. carnifex remain somewhat unclear. The two major hypothesized causes are the impacts of long-term climate change (both in the form of higher-frequency extreme weather events and more subtle shifts in temperature regimes, rainfall patterns, etc.), and hunting pressure and habitat changes imposed by humans. The latter option, however, appears to be much more likely.[25][26][27]

When modern humans first arrived in Australia, likely more than 60,000 years ago, it is thought that they had substantial impacts on the ecosystem by efficiently hunting large animals and by altering vegetation patterns through fire-stick farming. This has frequently been implicated in the disappearance of the majority of large Australian animals during the Pleistocene.

On the other hand, many Australian fossil sites appear to yield records of megafauna disappearance well before human presence in the area, giving weight to the interpretation that other factors, most likely climate-related, were the prominent drivers. However, most of these sites have been subject to heavy erosion, causing younger fossils to be reworked into older sediments. The question remains the subject of ongoing research.[28][29][30]

See also

- Australian megafauna

- Pleistocene megafauna

References

- ↑ Kilvert, Nick Complete skeleton of 'Tasmanian devil on steroids' reveals secrets of Australian 'stealth predator' ABC News, 13 December 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Thylacoleo (panel 1) at Western Australian Museum

- ↑ Wroe, S; Myers, T. J; Wells, R. T; Gillespie, A (1999). "Estimating the weight of the Pleistocene marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex (Thylacoleonidae:Marsupialia): Implications for the ecomorphology of a marsupial super-predator and hypotheses of impoverishment of Australian marsupial carnivore faunas". Australian Journal of Zoology 47 (5): 489–98. doi:10.1071/ZO99006.

- ↑ Wells, R.T.; Murray, P.F.; Bourne, S.J. (2009). "Pedal morphology of the marsupial lion Thylacoleo carnifex (Diprotodontia: Thylacoleonidae) from the Pleistocene of Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (4): 1335–1340. doi:10.1671/039.029.0424.

- ↑ "Bone Diggers – Anatomy of Thylacoleo". Nova. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/bonediggers/thyl-nf.html.

- ↑ Wells, R.T.; Camens, A.B. (2018). "New skeletal material sheds light on the palaeobiology of the Pleistocene marsupial carnivore, Thylacoleo carnifex". PLOS ONE 13 (12): e0208020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208020. PMID 30540785. Bibcode: 2018PLoSO..1308020W.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Naish, Darren (2004). "Of koalas and marsupial lions: the vombatiform radiation, part I". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33 (1): 240–250. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.05.004. PMID 15324852. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/tetrapod-zoology/2011/10/26/vombatiform-radiation-part-i/. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ "Thylacoleo". at National Dinosaur Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. https://web.archive.org/web/20140819085747/http://www.nationaldinosaurmuseum.com.au/Thylacoleo.htm.

- ↑ Thylacoleo carnifex at Australian Museum

- ↑ Gillespie, Anna K; Archer, Michael; Hand, Suzanne J (2016). "A tiny new marsupial lion (Marsupialia, Thylacoleonidae) from the early Miocene of Australia". Palaeontologia Electronica 19 (2). doi:10.26879/632.

- ↑ Wroe, S; McHenry, C; Thomason, J (2005). "Bite club: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272 (1563): 619–625. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. PMID 15817436.

- ↑ "Extinct Marsupial Lion Tops African Lion In Fight To Death", Science Daily, 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Marsupial lion was fast killer", The Australian, 18 January 2008.

- ↑ Monbiot, George (2014-04-03). "'Like a demon in a medieval book': is this how the marsupial lion killed prey?". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/georgemonbiot/2014/apr/03/australia-marsupial-lion-kangaroos-prey. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ "Marsupial lion 'could climb trees'". BBC News. 2016-02-15. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-35557269.

- ↑ Western Australian Museum Thylacoleo (panel 3) at Western Australian Museum

- ↑ Tyndale-Biscoe, Hugh (2005). Life of marsupials. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO. ISBN 978-0-643-09220-4.[page needed]

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Thylacoleo "The Beast of the Nullarbor", Catalyst, Western Australian Museum, Storyteller Media Group and ABC TV, 17 August 2006.

- ↑ "'Humans killed off Australia's giant beasts'". BBC News. 24 March 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-17488447.

- ↑ Ritchie, Euan G; Johnson, Christopher N (2009). "Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation". Ecology Letters 12 (9): 982–98. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01347.x. PMID 19614756.

- ↑ Black, Karen; Price, Gilbert J; Archer, Michael; Hand, Suzanne J (2014). "Bearing up well? Understanding the past, present and future of Australia's koalas". Gondwana Research 25 (3): 1186–201. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.12.008. Bibcode: 2014GondR..25.1186B.

- ↑ Amalfi, Carmelo (31 July 2002). "Beneath the desert, the past blooms". The Age (Melbourne). http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2002/07/30/1027926885416.html. Retrieved 2012-09-13.

- ↑ Carey, Stephen P; Camens, Aaron B; Cupper, Matthew L; Grün, Rainer; Hellstrom, John C; McKnight, Stafford W; McLennan, Iain; Pickering, David A et al. (2011). "A diverse Pleistocene marsupial trackway assemblage from the Victorian Volcanic Plains, Australia". Quaternary Science Reviews 30 (5–6): 591–610. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.11.021. Bibcode: 2011QSRv...30..591C.

- ↑ Camens, Aaron Bruce; Carey, Stephen Paul (2013). "Contemporaneous Trace and Body Fossils from a Late Pleistocene Lakebed in Victoria, Australia, Allow Assessment of Bias in the Fossil Record". PLOS ONE 8 (1): e52957. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052957. PMID 23301008. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...852957C.

- ↑ Bartlett, Lewis J; Williams, David R; Prescott, Graham W; Balmford, Andrew; Green, Rhys E; Eriksson, Anders; Valdes, Paul J; Singarayer, Joy S et al. (2016). "Robustness despite uncertainty: Regional climate data reveal the dominant role of humans in explaining global extinctions of Late Quaternary megafauna". Ecography 39 (2): 152–61. doi:10.1111/ecog.01566. https://research-information.bristol.ac.uk/files/80785540/Bartlett_et_al_2015.pdf.

- ↑ Sandom, C; Faurby, S; Sandel, B; Svenning, J.-C (2014). "Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281 (1787): 20133254. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3254. PMID 24898370.

- ↑ "Humans, not climate change, wiped out Australian megafauna". https://phys.org/news/2017-01-humans-climate-australian-megafauna.html.

- ↑ Wroe, S; Field, J. H; Archer, M; Grayson, D. K; Price, G. J; Louys, J; Faith, J. T; Webb, G. E et al. (2013). "Climate change frames debate over the extinction of megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (22): 8777–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302698110. PMID 23650401. Bibcode: 2013PNAS..110.8777W.

- ↑ Webb, R. Esmée (2015). "Megamarsupial extinction: The carrying capacity argument". Antiquity 72 (275): 46–55. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00086269.

- ↑ "The Extinction Enigma". PBS. May 1, 2007. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/evolution/extinction-enigma.html.

External links

- Anatomy of the Marsupial Lion (Interactive feature from Nova)

- Amos, Jonathan (5 April 2005). "Marsupial munch tops big biters". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4409039.stm.

- Fact sheet from Australian Museum Online

- Move Over Sabre-Tooth Tiger by Stephen Wroe from Australian Museum Online.

Wikidata ☰ Q685786 entry