Biology:Xenoturbella bocki

| Xenoturbella bocki | |

|---|---|

| |

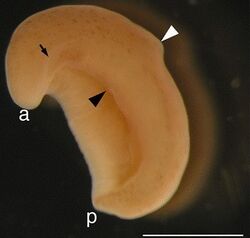

| X. bocki. Black arrow indicates side furrow. a is the anterior tip. p is the posterior tip. Black triangle indicates mouth. White triangle indicates circumferential furrow. The scale bar in the bottom right is 1 cm. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Xenacoelomorpha |

| Family: | Xenoturbellidae |

| Genus: | Xenoturbella |

| Species: | X. bocki

|

| Binomial name | |

| Xenoturbella bocki Westblad, 1949

| |

Xenoturbella bocki is a marine benthic worm-like species from the genus Xenoturbella. It is found in saltwater sea floor habitats off the coast of Europe, predominantly Sweden. It was the first species in the genus discovered. Initially it was collected by Swedish zoologist Sixten Bock in 1915, and described in 1949 by Swedish zoologist Einar Westblad.[1] The unusual digestive structure of this species, in which a single opening is used to eat food and excrete waste, has led to considerable study and controversy as to its classification. It is a bottom-dwelling, burrowing carnivore that eats mollusks (likely larval forms, as opposed to hard-shelled adults).

Systematics

Etymology

For the genus name Xenoturbella, Ancient Greek xénos, means foreign or strange, and Latin turbela, means a bustle or turbulence in water. Genus Xenoturbella is a member of sub-phylum Xenoturbellida, which are known as paradoxmaskar[2] – Swedish for "paradox worms" (a term that some popular media have applied to the species), because if it is classified as a deuterostome, it would be more closely related to humans than other, more complex, invertebrates such as lobsters.[3] Deuterostomes are a superphylum of animals whose anus forms before their mouth does during embryonic development. It includes humans, other chordates, echinoderms and hemichordates.

The species signifier bocki refers to Sixten Bock, who first collected the organism in 1915.[4] It was assigned by Swedish zoologist Einar Westblad, who described the species in 1949.

Taxonomy

In 1999, examination of X. bocki specimens held at the Swedish Museum of Natural History showed that a small subset of them must belong to another species.[5] This population differed from specimens identified as X. bocki in internal fertilization, its small size of 12 mm (0.47 in) at most, and its pink coloration – in contrast to yellow-white coloration identified for X. bocki. The new taxon was named after Westblad, who collected the specimens from coarser and shallower habitats in the same range as X. bocki. However, mitochondrial DNA sequencing from the specimens identified with both species suggested that the two populations belonged to the same species, involving that X. westbladi is a junior synonym to X. bocki.[6]

Phylogeny

Species level

Comparison of mitochondrial DNA and protein sequences showed that the species Xenoturbella bocki – often found off the coast of Sweden – is the sister group to X. hollandorum, a species discovered in 2016 in eastern Pacific Ocean.[7] In turn, these two species share evolutionary affinities with X. japonica into a clade of 'shallow-water' taxa.[8]

| Species-level cladogram of the genus Xenoturbella. |

| The cladogram has been reconstructed from mitochondrial DNA and protein sequences.[7][8] |

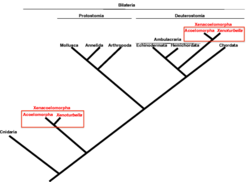

Above the genus level

When it was discovered, X. bocki was placed in a new genus Xenoturbella. Above the genus level, the classification of this animal is controversial. Westbald placed it in the phylum Platyhelminthes in the class Turbellaria (free-living flatworms).[9] In 1999, based on genetic analysis, it was placed in Protostomia by Israelsson, grouped with the bivalves.[10][11] Protostomia is a large clade including worms, mollusks and arthropods. In embryonic development, their mouth develops prior to the development of the anus for most protostomes, though some have evolved other developmental pathways. If placed in this clade, Xenoturbella would also be among these exceptions.[12]

However, today, this is understood as a misclassification due to contaminating DNA from its shellfish food. Swedish scientist Sarah J. Bourlat and her coauthors in 2006 placed it in its own phylum, Xenoturbellida. More recent studies suggest on the basis of genetic and developmental evidence (e.g. Hox genes) that it should be grouped with Acoela and Nemertodermatida into Acoelomorpha. These three taxa are sometimes placed within the deuterostomes (a large clade that includes humans and other chordates, sea stars and others),[12] while others classify these organisms as a basal offshoot that resembles a common ancestor of deuterostomes and protostomes.[11] A 2016 analysis of many genetic data sets supports the latter, and suggests that, like Xenoturbella bocki, the common ancestor of protostomes and deuterostomes likely had one opening, ciliated locomotion and a wormlike body.[13] However, if the deuterostome hypothesis is correct, then Xenoturbella must have lost many ancestral traits, such as an anus.[14]

Description

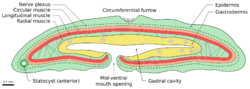

This animal usually grows to 1 cm (0.39 in) in length,[11] though individuals as long as 4 cm (1.6 in) have been reported.[11] Its nervous system consists of a nerve net with no defined brain or ganglia. The nerve net is found on the basal (away from the animal's surface) side of the skin.[15] This animal lacks a coelom. It also lacks an anus, excreting waste through the same opening as it intakes food.[9] Thus, the digestive organ is sac-like. The opening is on the belly of the animal, near the front. The animal is simultaneously hermaphroditic.[4]

A furrow runs along the circumference of the body in the middle of the animal. There are also side furrows. On its sides there are numerous tiny cilia that aid in locomotion. Small cells contain vesicles which may act as glands. An organ of unknown function, preliminarily called a statocyst, has been observed on the front end of the animal. Two leading hypotheses are that it aids in balance, as statocysts do in other invertebrates, or that it has endocrine functions. Experiments in which the animal was observed to cleave into two after a wound show that the statocyst is essential for normal behavior and long-term survival.[9]

Ecology

The animal moves through the water via rhythmic muscle contraction, aided by its side cilia, and a tuft of longer cilia on its back. The organism can also use its musculature to roll up into a ball, and maintain that form for several months.[9] Adults are known to have a symbiotic relationship with Chlamydiae and Gammaproteobacteria, two bacterial endosymbionts found in their gastrodermis.[16] Genetic data confirms that its diet includes bivalve mollusks.[11] However, it has never been observed feeding, so it is unknown if it eats bivalve carcasses, eggs, sperm, mucus, feces, or live larval or adult bivalves.[9] It lacks any visible means to get through the shells of adult bivalves. Captive specimens survived for several months without food, and showed no interest in any of the proposed food items afterwards. This has led some to suggest that it feeds by absorbing dissolved organic matter through its skin. At least one specimen that has been proposed to show a consumed bivalve larvae is preserved in the Swedish Natural History Museum. This species burrows, and has been observed to make tunnels as deep as 15 cm (5.9 in) into substrate in a laboratory aquarium.[9]

Range

This species has been found in ocean habitats off the coast of Europe, most often off the coast of Sweden. It is often collected using a Warén’s dredge from mud on the sea floor, at depths of 50–200 m (160–660 ft).[9][17]

Reproduction

X. bocki has only been observed to reproduce sexually.[9] In the wild, this species spawns in the winter. It lays small, mucus-coated eggs, which sink in the water column.[11] The eggs have a pale-orange color, and are opaque. Young, upon hatching, are yellowish, nearly spherical, and move to the surface of the water. Larvae lack a blastopore and do not feed until they are fully developed. They may derive nourishment from the yolk which would make them lecithotrophic. Within five days muscular contractions are observed in a laboratory setting, which may aid locomotion. X. bocki is a direct developer. As of 2013, this animal is extremely challenging to grow in captivity.[11]

References

- ↑ Westblad, E. (1949). "Xenoturbella bocki n. g., n. sp., a peculiar, primitive Turbellarian type". Arkiv för Zoologi 1: 3–29.

- ↑ "Xenoturbellida". https://www.dyntaxa.se/Taxon/Info/5000009?changeRoot=True.

- ↑ Jauregui, Andres (28 March 2013). "'Paradox Worm' Xenoturbella Bocki Lacks Brain & Sex Organs, But Could Be Mankind's 'Progenitor'". HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/paradox-worm-xenoturbella-mankind-progenitor_n_2964009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Telford, Maximilian J. (2008). "Xenoturbellida: The fourth deuterostome phylum and the diet of worms". Genesis 46 (11): 580–586. doi:10.1002/dvg.20414. ISSN 1526-968X. PMID 18821586.

- ↑ Israelsson, Olle (22 April 1999). "New light on the enigmatic Xenoturbella (phylum uncertain): ontogeny and phylogeny". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 266 (1421): 835–841. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0713.

- ↑ Rouse, Greg W.; Wilson, Nerida G.; Carvajal, Jose I.; Vrijenhoek, Robert C. (2016). "New deep-sea species of Xenoturbella and the position of Xenacoelomorpha". Nature 530 (7588): 94–97. doi:10.1038/nature16545. PMID 26842060. Bibcode: 2016Natur.530...94R.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Rouse, Greg W.; Wilson, Nerida G.; Carvajal, Jose I.; Vrijenhoek, Robert C. (2016-02-04). "New deep-sea species of Xenoturbella and the position of Xenacoelomorpha" (in en). Nature 530 (7588): 94–97. doi:10.1038/nature16545. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 26842060. Bibcode: 2016Natur.530...94R.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nakano, Hiroaki; Miyazawa, Hideyuki; Maeno, Akiteru; Shiroishi, Toshihiko; Kakui, Keiichi; Koyanagi, Ryo; Kanda, Miyuki; Satoh, Noriyuki et al. (2017-12-18). "A new species of Xenoturbella from the western Pacific Ocean and the evolution of Xenoturbella" (in en). BMC Evolutionary Biology 17 (1): 245. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-1080-2. ISSN 1471-2148. PMID 29249199.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Nakano, Hiroaki (2015). "What is Xenoturbella?". Zoological Letters 1 (22): 22. doi:10.1186/s40851-015-0018-z. PMID 26605067.

- ↑ Perseke, Marleen; Hankeln, Thomas; Weich, Bettina; Fritzsch, Guido; Stadler, Peter F.; Israelsson, Olle; Bernhard, Detlef; Schlegel, Martin (April 2007). "The Mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: Genomic Architecture and Phylogenetic Analysis". Theory in Biosciences 126 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7. PMID 18087755. http://ul.qucosa.de/id/qucosa%3A31999.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Nakano, H.; Lundin, K.; Bourlat, S. J.; Telford, M. J.; Funch, P.; Nyengaard, J. R.; Obst, M.; Thorndyke, M. C. (2013). "Xenoturbella bocki exhibits direct development with similarities to Acoelomorpha". Nature Communications 4: 1537. doi:10.1038/ncomms2556. PMID 23443565. Bibcode: 2013NatCo...4.1537N.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 de Mendoza, A.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. (2011). "The Mysterious Evolutionary Origin for the GNE Gene and the Root of Bilateria". Molecular Biology and Evolution 28 (11): 2987–2991. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr142. PMID 21616910.

- ↑ Cannon, J. T.; Vellutini, B. C.; Smith, J.; Ronquist, F.; Jondelius, U.; Hejnol, A. (2016). "Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa". Nature 530 (7588): 89–93. doi:10.1038/nature16520. PMID 26842059. Bibcode: 2016Natur.530...89C. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nrm:diva-1844.

- ↑ Philippe, H.; Brinkmann, H.; Copley, R. R.; Moroz, L. L.; Nakano, H.; Poustka, A. J.; Wallberg, A.; Peterson, K. J. et al. (2011). "Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella". Nature 470 (7333): 255–258. doi:10.1038/nature09676. PMID 21307940. Bibcode: 2011Natur.470..255P.

- ↑ Schmidt-Rhaesa, Andreas; Steffen, Harzsch; Günter, Purschke; Thomas, Stach (2016). Structure and Evolution of Invertebrate Nervous Systems (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191066214.

- ↑ Kjeldsen, K. U.; Obst, M.; Nakano, H.; Funch, P.; Schramm, A. (2010). "Two Types of Endosymbiotic Bacteria in the Enigmatic Marine Worm Xenoturbella bocki". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 76 (8): 2657–2662. doi:10.1128/aem.01092-09. PMID 20139320. Bibcode: 2010ApEnM..76.2657K.

- ↑ Nakano, Hiroaki; Miyazawa, Hideyuki; Maeno, Akiteru; Shiroishi, Toshihiko; Kakui, Keiichi; Koyanagi, Ryo; Kanda, Miyuki; Satoh, Noriyuki et al. (2017). "A new species of Xenoturbella from the western Pacific Ocean and the evolution of Xenoturbella". BMC Evolutionary Biology 17 (1): 245. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-1080-2. PMID 29249199.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q2225390 entry

|