Chemistry:Hemochromatosis

Haemochromatosis, also spelled hemochromatosis, is a hereditary disease characterized by improper processing by the body of dietary iron which causes iron to accumulate in a number of body tissues,[1] eventually causing organ dysfunction. It is the most common iron overload disorder.

History

The disease was first described in 1865 by Armand Trousseau in an article on diabetes.[2] Trousseau did not make the link with iron accumulation: This was done by Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen in 1890.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

Haemochromatosis is notoriously protean, i.e., it presents with symptoms that are often initially attributed to other diseases. It is also true that some people with the disease never actually show signs or suffer symptoms (i.e. is clinically silent).[5]

Symptoms may include [6][7][8]:

- Malaise

- Liver cirrhosis (with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, affecting up to a third of all homozygotes) - this is often preceded by a period of a painfully enlarged liver.

- Insulin resistance (often patients have already been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2)

- Erectile dysfunction and hypogonadism

- Decreased libido

- Congestive heart failure, arrhythmias or pericarditis

- Arthritis of the hands (MCP and PIP joints), knee and shoulder joints

- Deafness[9]

- Dyskinesias, including Parkinsonian symptoms[10] [9] [11]

- Dysfunction of certain endocrine organs:

- Pancreatic gland

- Adrenal gland (leading to adrenal insufficiency)

- Parathyroid gland (leading to hypocalcaemia)

- Pituitary gland

- Testes or ovary (leading to hypogonadism)

- A darkish colour to the skin (see pigmentation, hence its name Diabete bronze when it was first described by Armand Trousseau in 1865)

- An increased susceptibility to certain infectious diseases caused by:

- Vibrio vulnificus infections from eating seafood

- Listeria monocytogenes

- Yersinia enterocolica

- Salmonella enteritidis (serotype Typhymurium)

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Escherichia coli

- Rhizopus arrhizus

- Mucor species

Males are usually diagnosed after their forties, and women about a decade later, owing to regular iron loss by menstruation (which ceases in menopause), but cases have been found in young children as well.

Diagnosis

Haemochromatosis is difficult to diagnose in the early stages. Early signs may mimic other diseases. Stiff joints and fatigue for example are common in haemochromatosis and other maladies.[12]

Imaging features

Clinically the disease may be silent, but characteristic radiological features may point to the diagnosis. The increased iron stores in the organs involved, especially in the liver and pancreas, result in an increased attenuation at unenhanced CT and a decreased signal intensity at MR imaging. Haemochromatosis arthropathy includes degenerative osteoarthritis and chondrocalcinosis. The distribution of the arthropathy is distinctive, but not unique, frequently affecting the second and third metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand.[citation needed]

Chemistry

Serum transferrin saturation: A first step is the measurement of transferrin, the protein which chemically binds to iron and carries it through the blood to the liver, spleen and bone marrow[13]. Measuring transferrin provides a measurement of iron in the blood. Saturation values of 45% are too high.[14]

Serum Ferritin: Ferritin, the protein which chemically binds to iron and stores it in the body. Measuring ferritin provides a measurement of iron in the whole body. Normal values for males are 12-300 ng/ml (nanograms per milliliter) and for female, 12-150 ng/ml. Low values indicate iron deficiency which may be attributed to a number of causes. Higher than normal also may indicate other causes including haemochromatosis.[15][16]

Other blood tests routinely performed: blood count, renal function, liver enzymes, electrolytes, glucose (and/or an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)).

Based on the history, the doctor might consider specific tests to monitor organ dysfunction, such as an echocardiogram for heart failure.

Histopathology

Liver biopsy - Liver biopsies involve taking a sample of tissue from your liver, using a thin needle. The sample is then checked for the presence of iron as well as for evidence of liver damage (particularly cirrhosis: tissue scarring). Formerly, this was the only way to confirm a diagnosis of hemochromatosis but measures of transferrin and ferritin along with a history are considered better options in determining the presence of the malady. Risks of biopsy include bruising, bleeding and infection. Now, when a history and measures of transferrin or ferritin point to haemochromatosis, it is debatable whether a liver biopsy still needs to occur to quantify the amount of accumulated iron. [17]

Screening

Screening specifically means looking for a disease in people who have no symptoms. Diagnosis, on the other hand refers to testing people who have symptoms of a disease. Standard diagnostic measures for haemochromatosis, serum transferrin saturation and serum ferritin tests, aren't a part of routine medical testing. Screening for hemochromatosis is recommended if the patient has a parent, child or sibling with the disease, or have any of the following signs and symptoms: [18][19]

- Joint disease

- Severe fatigue

- Heart disease

- Elevated liver enzymes

- Impotence

- Diabetes

Genetic screening does not have any apparent advantages and treatment based on screening results are not demonstrably efficacious. Given that the malady is very rare in the general population, genetic carriers of the disease may never manifest the symptoms of the disease and the potential harm of the attendant surveillance, labeling, unnecessary invasive work-up, anxiety, and, potentially, unnecessary treatments outweigh the potential benefits. [20]

Differential diagnosis

There exist other causes of excess iron accumulation, which have to be considered before Haemochromatosis is diagnosed.

- African iron overload, formerly known as Bantu siderosis, was first observed among people of African descent in Southern Africa. Originally, this was blamed on ungalvanised barrels used to store home-made beer, which led to increased oxidation and increased iron levels in the beer. Further investigation has shown that only some people drinking this sort of beer get an iron overload syndrome, and that a similar syndrome occurred in people of African descent who have had no contact with this kind of beer (e.g., African Americans). This led investigators to the discovery of a gene polymorphism in the gene for ferroportin which predisposes some people of African descent to iron overload.[21]

- Transfusion hemosiderosis is the accumulation of iron, mainly in the liver, in patients who receive frequent blood transfusions (such as those with thalassemia).

- Dyserythropoeisis is a disorder in the production of red blood cells. This leads to increased iron recycling from the bone marrow and accumulation in the liver.

Epidemiology

Hemochromatosis is one of the most common inheritable genetic defects, especially in people of northern European extraction, with about 1 in 10 people carrying the defective gene. The prevalence of haemochromatosis varies in different populations. In Northern Europeans it is of the order of one in 400 persons. A study of 3,011 unrelated white Australians found that 14% were carriers and 0.5% had the genetic condition.[22] Other populations probably have a lower prevalence of this disease. It is presumed, through genetic studies, that the "first" haemochromatosis patient, possibly of Celtic ethnicity, lived 60-70 generations ago. Around that time, when diet was poor, the presence of a mutant allelle may have provided a heterozygous advantage in maintaining sufficient iron levels in the blood. With our current rich diets, this 'extra help' is unnecessary and indeed harmful.

Genetics

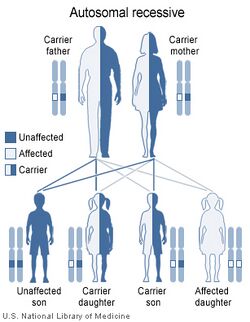

The gene that controls the amount of iron absorbed from food is called HFE. The HFE gene has two common mutations, C282Y and H63D.[23]

Inheriting just one of the C282Y mutations (heterozygous) makes a person a carrier who can pass this mutation onward. One mutation may lead to slightly excessive iron absorbtion but usually haemochromatosis does not develop.

In the United States, most people with haemochromatosis have inherited two copies of C282Y — one from each parent — and are homozygous for the trait. Mutations of the HFE gene account for 90% of the cases. This gene is closely linked to the HLA-A3 locus. Homozygosity for the C282Y mutation is the most important one, although the heterozygosity C282Y/H63D mutations are also associated to disease (both conditions are sufficient to reach the diagnosis). Carriers of a single copy of either gene have a very slight risk of haemochromatosis when other factors contribute, but are otherwise healthy.[24]

Even if an individual has both copies of the abnormal gene the risk of actual clinical haemochromatosis is low (between 1—25%) due to incomplete penetrance. The variability in these estimates is probably due to different populations studied and how penetrance was defined.[citation needed]

Other genes that cause haemochromatosis are the autosomal dominant SLC11A3/ferroportin 1 gene and TfR2 (transferrin receptor 2). They are much rarer than HFE-haemochromatosis.

Recently, a classification has been developed (with chromosome locations):

- Haemochromatosis type 1 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 235200): "classical" HFE-haemochromatosis (6p21.3).

- Haemochromatosis type 2 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 602390): juvenile haemochromatosis :

- Type 2A:(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 602390): mutations in hemojuvelin ("HJV", also known as HFE2)

- Type 2B (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 606464): mutation in hepcidin antimicrobial peptide (HAMP) or HFE2B (19q13)

- Haemochromatosis type 3 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 604720): transferrin receptor-2 (TFR2 or HFE3, 7q22).

- Haemochromatosis type 4 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 604653): autosomal dominant haemochromatosis (all others are recessive), ferroportin (SLC11A3) gene mutation (2q32).

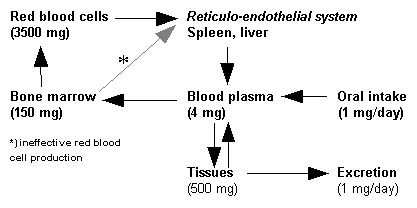

Pathophysiology

People with the abnormal genes do not reduce their absorption of iron in response to increased iron levels in the body. Thus the iron stores of the body increase. As they increase the iron which is initially stored as ferritin starts to get stored as a breakdown product of ferritin called haemosiderin and this is toxic to tissue, probably at least partially by inducing Oxidative stress.[25]

Crypt cell hypothesis

The sensor pathway inside the enterocyte is disrupted due to the genetic errors. The enterocyte in the crypt must sense the amount of circulating iron. Depending on this information, the cell can regulate the quantity of receptors and channel proteins for iron. If there is little iron, the cell will express many of these proteins. If there is a lot, the cell will turn off the expression of this transporters.

In haemochromatosis, the cell is constantly fooled into thinking there is iron depletion. As a consequence, it overexpresses the necessary channel proteins, this leading to a massive, and unnecessary iron absorption.

These proteins are named DMT-1 (divalent metal transporter), for the luminal side of the cell, and ferroportin, the only known cellular iron exporter, for the basal side of the cell.

Hepcidin-ferroportin axis

Recently, a new unifying theory for the pathogenesis of hereditary hemochromatosis has been proposed that focuses on the hepcidin-ferroportin regulatory axis. Inappropriately low levels of hepcidin, the iron regulatory hormone, can account for the clinical phenotype of hereditary hemochromatosis. In this view, low levels of circulating hepcidin result in higher levels of ferroportin expression in intestinal epithelial cells and reticuloendothelial macrophages. As a result, this causes increased levels of serum iron, first biochemically detected as increasing transferrin saturation. HFE, hemojuvelin, BMP's and TFR2 are implicated in regulating hepcidin expression. Higher serum iron levels lead to progressive iron loading in tissues.

Complications

Iron is stored in the liver, the pancreas and the heart. Long term effects of haemochromatosis on these organs can be very serious, even fatal when untreated. [26]

Cirrhosis: Permanent scarring of the liver. Along with other maladies like long-term alcoholism, haemochromatosis may have an adverse effect on the liver. The liver is a primary storage area for iron and will naturally accumulate excess iron. Over time the liver is likely to be damaged by iron overload. Cirrhosis itself may lead to additional and more serious complications, including bleeding from dilated veins in the esophagus and stomach (varices) and severe fluid retention in the abdomen (ascites). Toxins may accumulate in your blood and eventually affect mental functioning. This can lead to confusion or even coma (hepatic encephalopathy).

Liver cancer: Cirrhosis and haemochromatosis together will increase the risk of liver cancer. (Nearly one-third of people with haemochromatosis and cirrhosis eventually develop liver cancer.)

Diabetes: The pancreas which also stores iron is very important in the body’s mechanisms for sugar metabolism. Diabetes affects the way the body uses blood sugar (glucose). Diabetes is in turn the leading cause of new blindness in adults and may be involved in kidney failure and cardiovascular disease.

Congestive heart failure: If excess iron in the heart interferes with the its ability to circulate enough blood, a number of problems can occur including death. The condition may be reversible when haemochromatosis is treated and excess iron stores reduced.

Heart arrhythmias: Arrhythmia or abnormal heart rhythms can cause heart palpitations, chest pain and light-headedness and are occasionally life threatening. This condition can often be reversed with treatment for haemochromatosis.

Pigment changes: Deposits of iron in skin cells can turn skin a bronze or gray color.

Treatment

Early diagnosis is important because the late effects of iron accumulation can be wholly prevented by periodic phlebotomies (by venesection) comparable in volume to blood donations.[27] Treatment is initiated when ferritin levels reach 300 micrograms per litre (or 200 in nonpregnant premenopausal women).

Every bag of blood (450-500 ml) contains 200-250 milligrams of iron. Phlebotomy (or bloodletting) is usually done at a weekly interval until ferritin levels are less than 50 nanograms per millilitre. After that, 1-4 donations per year are usually needed to maintain iron balance.

Other parts of the treatment include:

- Treatment of organ damage (heart failure with diuretics and ACE inhibitor therapy).

- Limiting intake of alcoholic beverages, vitamin C (increases iron absorption in the gut), red meat (high in iron) and potential causes of food poisoning (shellfish, seafood).

- Increasing intake of substances that inhibit iron absorption, such as high-tannin tea, calcium, and foods containing oxalic and phytic acids (these must be consumed at the same time as the iron-containing foods in order to be effective.)

References

- ↑ Iron Overload and Hemochromatosis Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ Trousseau A (1865). "Glycosurie, diabète sucré". Clinique médicale de l'Hôtel-Dieu de Paris 2: 663–98.

- ↑ von Recklinghausen FD (1890). "Hämochromatose". Tageblatt der Naturforschenden Versammlung 1889: 324.

- ↑ Biography of Daniel von Recklinghausen

- ↑ Hemochromatosis-Diagnosis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- ↑ Iron Overload and Hemochromatosis Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ Hemochromatosis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- ↑ Hemochromatosis-Signs and Symptoms Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jones H, Hedley-Whyte E (1983). "Idiopathic hemochromatosis (IHC): dementia and ataxia as presenting signs". Neurology 33 (11): 1479-83. PMID 6685241.

- ↑ Costello D, Walsh S, Harrington H, Walsh C (2004). "Concurrent hereditary haemochromatosis and idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a case report series". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75 (4): 631-3. PMID 15026513.

- ↑ Nielsen J, Jensen L, Krabbe K (1995). "Hereditary haemochromatosis: a case of iron accumulation in the basal ganglia associated with a parkinsonian syndrome". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 59 (3): 318-21. PMID 7673967.

- ↑ Screening and Diagnosis

- ↑ Transferrin and Iron Transport Physiology

- ↑ Screening and Diagnosis

- ↑ Screening and Diagnosis

- ↑ Ferritin Test Measuring iron in the body

- ↑ Screening and diagnosis Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER) Retreived 18 March, 2007

- ↑ Screening and Diagnosis Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). Retreived 18 March, 2007

- ↑ Screening for Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Recommendations from the American College of Physicians Annals of Internal Medicine (2005) 4 October, Volume 143 Issue 7. (Page I-46). American College of Physicians. Retreived 18 March, 2007

- ↑ Screening for Hemochromatosis U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2006). Summary of Screening Recommendations and Supporting Documents. Retreived 18 March, 2007

- ↑ Gordeuk V, Caleffi A, Corradini E, Ferrara F, Jones R, Castro O, Onyekwere O, Kittles R, Pignatti E, Montosi G, Garuti C, Gangaidzo I, Gomo Z, Moyo V, Rouault T, MacPhail P, Pietrangelo A (2003). "Iron overload in Africans and African-Americans and a common mutation in the SCL40A1 (ferroportin 1) gene". Blood Cells Mol Dis 31 (3): 299-304. PMID 14636642.

- ↑ Olynyk J, Cullen D, Aquilia S, Rossi E, Summerville L, Powell L (1999). "A population-based study of the clinical expression of the hemochromatosis gene". N Engl J Med 341 (10): 718-24. PMID 10471457.

- ↑ Hemochromatosis-Causes Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER) Retreived March 12, 2007

- ↑ Hemochromatosis-Causes Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER) Retreived March 12, 2007

- ↑ Shizukuda Y, Bolan C, Nguyen T, Botello G, Tripodi D, Yau Y, Waclawiw M, Leitman S, Rosing D (2007). "Oxidative stress in asymptomatic subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis". Am J Hematol 82 (3): 249-50. PMID 16955456.

- ↑ Haemochromatosis Complications

- ↑ Hemochromatosis - Treatment

See also

- Cirrhosis

External links

- American Hemochromatosis Society

- International Bioiron Society

- Canadian Hemochromatosis Society

- Haemochromatosis page

- "The Bronze Killer" Mary Warder's book on Hemochromatosis

- Causes of Haemochromatosis

- Iron Toxicity, What you don't know

- Andrews N (1999). "Disorders of iron metabolism". New England Journal of Medicine 341 (26): 1986-95. PMID 10607817. link

- Haemochromatosis Society, UK

- Haemochromatosis Society Australia Inc

- Hemachromatosis page at the National Center for Biotechnology Information

Template:Hematology de:Hämochromatose es:Hemocromatosis fr:Hémochromatose génétique it:Emocromatosi he:המוכרומטוזיס nl:Hemochromatose no:Hemokromatose pl:Hemochromatoza pt:Hemocromatose fi:Hemokromatoosi sv:Hemakromotos