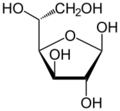

Chemistry:Glucose

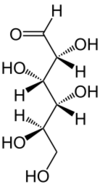

Skeletal formula of d-glucose

| |

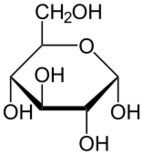

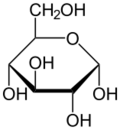

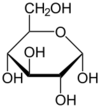

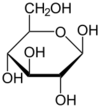

Haworth projection of α-d-glucopyranose

| |

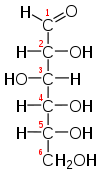

Fischer projection of d-glucose

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡluːkoʊz/, /ɡluːkoʊs/ |

| IUPAC name

Allowed trivial names:[1]

| |

| Preferred IUPAC name

PINs are not identified for natural products. | |

Systematic IUPAC name

| |

| Other names

Blood sugars

Dextrose Corn sugar d-Glucose Grape sugar | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| Abbreviations | Glc |

| 1281604 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

| 83256 | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Glucose |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.156 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Density | 1.54 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | α-d-Glucose: 146 °C (295 °F; 419 K) β-d-Glucose: 150 °C (302 °F; 423 K) |

| 909 g/L (25 °C (77 °F)) | |

| −101.5×10−6 cm3/mol | |

| 8.6827 | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

218.6 J/(K·mol)[2] |

Std molar

entropy (S |

209.2 J/(K·mol)[2] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1271 kJ/mol[3] |

| Pharmacology | |

| 1=ATC code }} | B05CX01 (WHO) V04CA02 (WHO), V06DC01 (WHO) |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 08655 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Glucose is a sugar with the molecular formula C

6H

12O

6. Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide,[4] a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight, where it is used to make cellulose in cell walls, the most abundant carbohydrate in the world.[5]

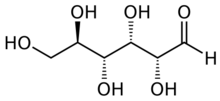

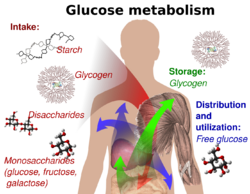

In energy metabolism, glucose is the most important source of energy in all organisms. Glucose for metabolism is stored as a polymer, in plants mainly as starch and amylopectin, and in animals as glycogen. Glucose circulates in the blood of animals as blood sugar. The naturally occurring form of glucose is d-glucose, while its stereoisomer l-glucose is produced synthetically in comparatively small amounts and is less biologically active.[6] Glucose is a monosaccharide containing six carbon atoms and an aldehyde group, and is therefore an aldohexose. The glucose molecule can exist in an open-chain (acyclic) as well as ring (cyclic) form. Glucose is naturally occurring and is found in its free state in fruits and other parts of plants. In animals, glucose is released from the breakdown of glycogen in a process known as glycogenolysis.

Glucose, as intravenous sugar solution, is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] It is also on the list in combination with sodium chloride.[7]

The name glucose is derived from Ancient Greek γλεῦκος (gleûkos, "wine, must"), from γλυκύς (glykýs, "sweet").[8][9] The suffix "-ose" is a chemical classifier, denoting a sugar.

History

Glucose was first isolated from raisins in 1747 by the German chemist Andreas Marggraf.[10][11] Glucose was discovered in grapes by another German chemist – Johann Tobias Lowitz – in 1792, and distinguished as being different from cane sugar (sucrose). Glucose is the term coined by Jean Baptiste Dumas in 1838, which has prevailed in the chemical literature. Friedrich August Kekulé proposed the term dextrose (from the Latin dexter, meaning "right"), because in aqueous solution of glucose, the plane of linearly polarized light is turned to the right. In contrast, l-fructose (usually referred to as d-fructose) (a ketohexose) and l-glucose (l-glucose) turn linearly polarized light to the left. The earlier notation according to the rotation of the plane of linearly polarized light (d and l-nomenclature) was later abandoned in favor of the d- and l-notation, which refers to the absolute configuration of the asymmetric center farthest from the carbonyl group, and in concordance with the configuration of d- or l-glyceraldehyde.[12][13]

Since glucose is a basic necessity of many organisms, a correct understanding of its chemical makeup and structure contributed greatly to a general advancement in organic chemistry. This understanding occurred largely as a result of the investigations of Emil Fischer, a German chemist who received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his findings.[14] The synthesis of glucose established the structure of organic material and consequently formed the first definitive validation of Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff's theories of chemical kinetics and the arrangements of chemical bonds in carbon-bearing molecules.[15] Between 1891 and 1894, Fischer established the stereochemical configuration of all the known sugars and correctly predicted the possible isomers, applying Van 't Hoff's theory of asymmetrical carbon atoms. The names initially referred to the natural substances. Their enantiomers were given the same name with the introduction of systematic nomenclatures, taking into account absolute stereochemistry (e.g. Fischer nomenclature, d/l nomenclature).

For the discovery of the metabolism of glucose Otto Meyerhof received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1922.[16] Hans von Euler-Chelpin was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Arthur Harden in 1929 for their "research on the fermentation of sugar and their share of enzymes in this process".[17][18] In 1947, Bernardo Houssay (for his discovery of the role of the pituitary gland in the metabolism of glucose and the derived carbohydrates) as well as Carl and Gerty Cori (for their discovery of the conversion of glycogen from glucose) received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[19][20][21] In 1970, Luis Leloir was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of glucose-derived sugar nucleotides in the biosynthesis of carbohydrates.[22]

Chemical and physical properties

Glucose forms white or colorless solids that are highly soluble in water and acetic acid but poorly soluble in methanol and ethanol. They melt at 146 °C (295 °F) (α) and 150 °C (302 °F) (β), and decompose starting at 188 °C (370 °F) with release of various volatile products, ultimately leaving a residue of carbon.[23] Glucose has a pK value of 12.16 at 25 °C (77 °F) in water.[24]

With six carbon atoms, it is classed as a hexose, a subcategory of the monosaccharides. d-Glucose is one of the sixteen aldohexose stereoisomers. The d-isomer, d-glucose, also known as dextrose, occurs widely in nature, but the l-isomer, l-glucose, does not. Glucose can be obtained by hydrolysis of carbohydrates such as milk sugar (lactose), cane sugar (sucrose), maltose, cellulose, glycogen, etc. Dextrose is commonly commercially manufactured from cornstarch in the US and Japan, from potato and wheat starch in Europe, and from tapioca starch in tropical areas.[25] The manufacturing process uses hydrolysis via pressurized steaming at controlled pH in a jet followed by further enzymatic depolymerization.[26] Unbonded glucose is one of the main ingredients of honey.

Structure and nomenclature

Glucose is usually present in solid form as a monohydrate with a closed pyran ring (α-glucopyranose monohydrate, sometimes known less precisely by dextrose hydrate). In aqueous solution, on the other hand, it is an open-chain to a small extent and is present predominantly as α- or β-pyranose, which interconvert. From aqueous solutions, the three known forms can be crystallized: α-glucopyranose, β-glucopyranose and α-glucopyranose monohydrate.[27] Glucose is a building block of the disaccharides lactose and sucrose (cane or beet sugar), of oligosaccharides such as raffinose and of polysaccharides such as starch, amylopectin, glycogen, and cellulose. The glass transition temperature of glucose is 31 °C (88 °F) and the Gordon–Taylor constant (an experimentally determined constant for the prediction of the glass transition temperature for different mass fractions of a mixture of two substances)[28] is 4.5.[29]

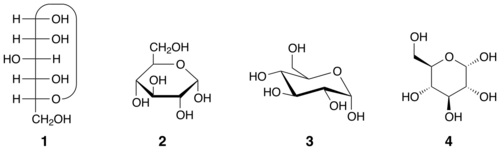

| Forms and projections of d-glucose in comparison | ||

|---|---|---|

| Natta projection | Haworth projection | |

|

α-d-glucofuranose α-d-glucofuranose

|

β-d-glucofuranose β-d-glucofuranose

|

α-d-glucopyranose α-d-glucopyranose

|

β-d-glucopyranose β-d-glucopyranose

| |

| α-d-Glucopyranose in (1) Tollens/Fischer (2) Haworth projection (3) chair conformation (4) Mills projection | ||

| ||

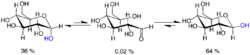

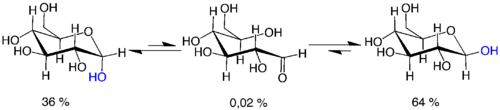

Open-chain form

The open-chain form of glucose makes up less than 0.02% of the glucose molecules in an aqueous solution at equilibrium.[30] The rest is one of two cyclic hemiacetal forms. In its open-chain form, the glucose molecule has an open (as opposed to cyclic) unbranched backbone of six carbon atoms, where C-1 is part of an aldehyde group H(C=O)–. Therefore, glucose is also classified as an aldose, or an aldohexose. The aldehyde group makes glucose a reducing sugar giving a positive reaction with the Fehling test.

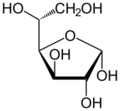

Cyclic forms

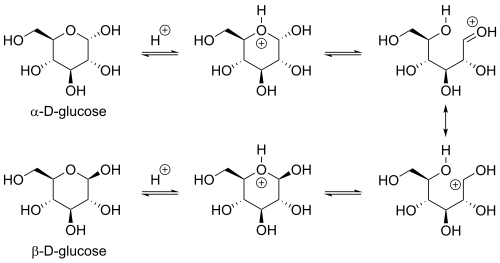

In solutions, the open-chain form of glucose (either "D-" or "L-") exists in equilibrium with several cyclic isomers, each containing a ring of carbons closed by one oxygen atom. In aqueous solution, however, more than 99% of glucose molecules exist as pyranose forms. The open-chain form is limited to about 0.25%, and furanose forms exist in negligible amounts. The terms "glucose" and "D-glucose" are generally used for these cyclic forms as well. The ring arises from the open-chain form by an intramolecular nucleophilic addition reaction between the aldehyde group (at C-1) and either the C-4 or C-5 hydroxyl group, forming a hemiacetal linkage, –C(OH)H–O–.

The reaction between C-1 and C-5 yields a six-membered heterocyclic system called a pyranose, which is a monosaccharide sugar (hence "-ose") containing a derivatised pyran skeleton. The (much rarer) reaction between C-1 and C-4 yields a five-membered furanose ring, named after the cyclic ether furan. In either case, each carbon in the ring has one hydrogen and one hydroxyl attached, except for the last carbon (C-4 or C-5) where the hydroxyl is replaced by the remainder of the open molecule (which is –(C(CH

2OH)HOH)–H or –(CHOH)–H respectively).

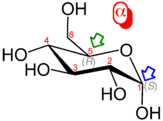

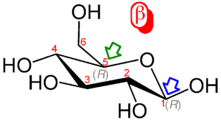

The ring-closing reaction can give two products, denoted "α-" and "β-". When a glucopyranose molecule is drawn in the Haworth projection, the designation "α-" means that the hydroxyl group attached to C-1 and the –CH

2OH group at C-5 lies on opposite sides of the ring's plane (a trans arrangement), while "β-" means that they are on the same side of the plane (a cis arrangement). Therefore, the open-chain isomer D-glucose gives rise to four distinct cyclic isomers: α-D-glucopyranose, β-D-glucopyranose, α-D-glucofuranose, and β-D-glucofuranose. These five structures exist in equilibrium and interconvert, and the interconversion is much more rapid with acid catalysis.

The other open-chain isomer L-glucose similarly gives rise to four distinct cyclic forms of L-glucose, each the mirror image of the corresponding D-glucose.

The glucopyranose ring (α or β) can assume several non-planar shapes, analogous to the "chair" and "boat" conformations of cyclohexane. Similarly, the glucofuranose ring may assume several shapes, analogous to the "envelope" conformations of cyclopentane.

In the solid state, only the glucopyranose forms are observed.

Some derivatives of glucofuranose, such as 1,2-O-isopropylidene-D-glucofuranose are stable and can be obtained pure as crystalline solids.[31][32] For example, reaction of α-D-glucose with para-tolylboronic acid H

3C–(C

6H

4)–B(OH)

2 reforms the normal pyranose ring to yield the 4-fold ester α-D-glucofuranose-1,2:3,5-bis(p-tolylboronate).[33]

Mutarotation

Mutarotation consists of a temporary reversal of the ring-forming reaction, resulting in the open-chain form, followed by a reforming of the ring. The ring closure step may use a different –OH group than the one recreated by the opening step (thus switching between pyranose and furanose forms), or the new hemiacetal group created on C-1 may have the same or opposite handedness as the original one (thus switching between the α and β forms). Thus, though the open-chain form is barely detectable in solution, it is an essential component of the equilibrium.

The open-chain form is thermodynamically unstable, and it spontaneously isomerizes to the cyclic forms. (Although the ring closure reaction could in theory create four- or three-atom rings, these would be highly strained, and are not observed in practice.) In solutions at room temperature, the four cyclic isomers interconvert over a time scale of hours, in a process called mutarotation.[34] Starting from any proportions, the mixture converges to a stable ratio of α:β 36:64. The ratio would be α:β 11:89 if it were not for the influence of the anomeric effect.[35] Mutarotation is considerably slower at temperatures close to 0 °C (32 °F).

Optical activity

Whether in water or the solid form, d-(+)-glucose is dextrorotatory, meaning it will rotate the direction of polarized light clockwise as seen looking toward the light source. The effect is due to the chirality of the molecules, and indeed the mirror-image isomer, l-(−)-glucose, is levorotatory (rotates polarized light counterclockwise) by the same amount. The strength of the effect is different for each of the five tautomers.

Note that the d- prefix does not refer directly to the optical properties of the compound. It indicates that the C-5 chiral centre has the same handedness as that of d-glyceraldehyde (which was so labelled because it is dextrorotatory). The fact that d-glucose is dextrorotatory is a combined effect of its four chiral centres, not just of C-5; and indeed some of the other d-aldohexoses are levorotatory.

The conversion between the two anomers can be observed in a polarimeter since pure α-d-glucose has a specific rotation angle of +112.2° mL/(dm·g), pure β-d-glucose of +17.5° mL/(dm·g).[36] When equilibrium has been reached after a certain time due to mutarotation, the angle of rotation is +52.7° mL/(dm·g).[36] By adding acid or base, this transformation is much accelerated. The equilibration takes place via the open-chain aldehyde form.

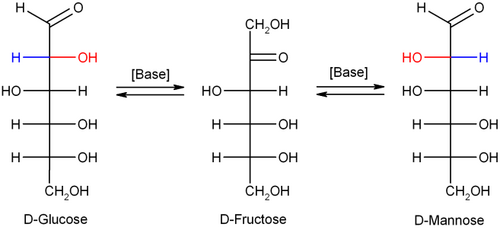

Isomerisation

In dilute sodium hydroxide or other dilute bases, the monosaccharides mannose, glucose and fructose interconvert (via a Lobry de Bruyn–Alberda–Van Ekenstein transformation), so that a balance between these isomers is formed. This reaction proceeds via an enediol:

Biochemical properties

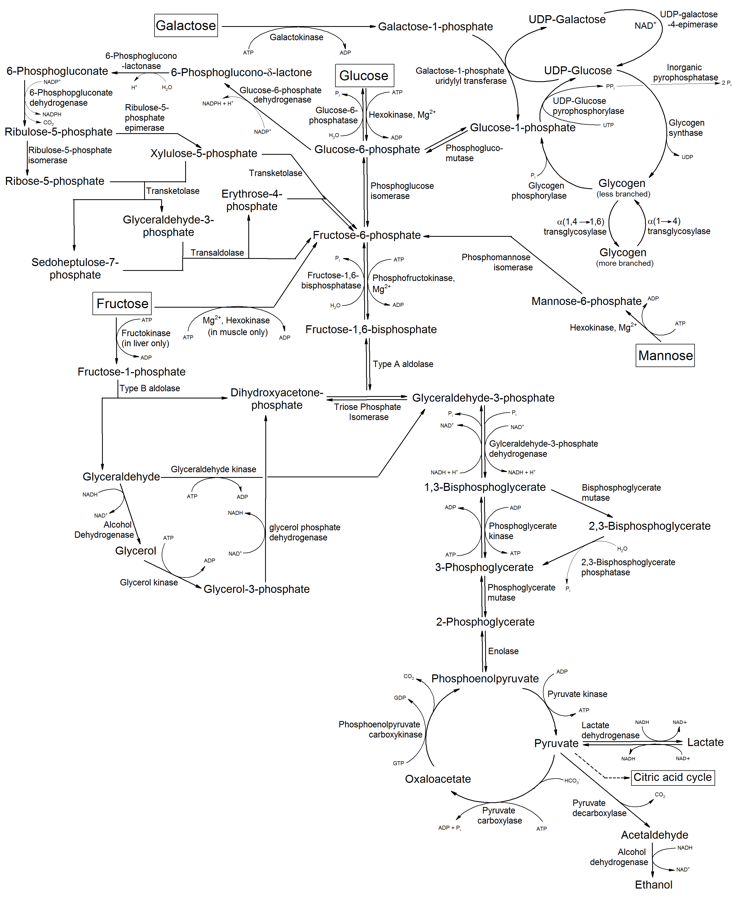

| Metabolism of common monosaccharides and some biochemical reactions of glucose |

|---|

Glucose is the most abundant monosaccharide. Glucose is also the most widely used aldohexose in most living organisms. One possible explanation for this is that glucose has a lower tendency than other aldohexoses to react nonspecifically with the amine groups of proteins.[37] This reaction—glycation—impairs or destroys the function of many proteins,[37] e.g. in glycated hemoglobin. Glucose's low rate of glycation can be attributed to its having a more stable cyclic form compared to other aldohexoses, which means it spends less time than they do in its reactive open-chain form.[37] The reason for glucose having the most stable cyclic form of all the aldohexoses is that its hydroxy groups (with the exception of the hydroxy group on the anomeric carbon of d-glucose) are in the equatorial position. Presumably, glucose is the most abundant natural monosaccharide because it is less glycated with proteins than other monosaccharides.[37][38] Another hypothesis is that glucose, being the only d-aldohexose that has all five hydroxy substituents in the equatorial position in the form of β-d-glucose, is more readily accessible to chemical reactions,[39]:194, 199 for example, for esterification[40]:363 or acetal formation.[41] For this reason, d-glucose is also a highly preferred building block in natural polysaccharides (glycans). Polysaccharides that are composed solely of glucose are termed glucans.

Glucose is produced by plants through photosynthesis using sunlight, water and carbon dioxide and can be used by all living organisms as an energy and carbon source. However, most glucose does not occur in its free form, but in the form of its polymers, i.e. lactose, sucrose, starch and others which are energy reserve substances, and cellulose and chitin, which are components of the cell wall in plants or fungi and arthropods, respectively. These polymers, when consumed by animals, fungi and bacteria, are degraded to glucose using enzymes. All animals are also able to produce glucose themselves from certain precursors as the need arises. Neurons, cells of the renal medulla and erythrocytes depend on glucose for their energy production.[42] In adult humans, there is about 18 g (0.63 oz) of glucose,[43] of which about 4 g (0.14 oz) is present in the blood.[44] Approximately 180–220 g (6.3–7.8 oz) of glucose is produced in the liver of an adult in 24 hours.[43]

Many of the long-term complications of diabetes (e.g., blindness, kidney failure, and peripheral neuropathy) are probably due to the glycation of proteins or lipids.[45] In contrast, enzyme-regulated addition of sugars to protein is called glycosylation and is essential for the function of many proteins.[46]

Uptake

Ingested glucose initially binds to the receptor for sweet taste on the tongue in humans. This complex of the proteins T1R2 and T1R3 makes it possible to identify glucose-containing food sources. Glucose mainly comes from food—about 300 g (11 oz) per day is produced by conversion of food,[47] but it is also synthesized from other metabolites in the body's cells. In humans, the breakdown of glucose-containing polysaccharides happens in part already during chewing by means of amylase, which is contained in saliva, as well as by maltase, lactase, and sucrase on the brush border of the small intestine. Glucose is a building block of many carbohydrates and can be split off from them using certain enzymes. Glucosidases, a subgroup of the glycosidases, first catalyze the hydrolysis of long-chain glucose-containing polysaccharides, removing terminal glucose. In turn, disaccharides are mostly degraded by specific glycosidases to glucose. The names of the degrading enzymes are often derived from the particular poly- and disaccharide; inter alia, for the degradation of polysaccharide chains there are amylases (named after amylose, a component of starch), cellulases (named after cellulose), chitinases (named after chitin), and more. Furthermore, for the cleavage of disaccharides, there are maltase, lactase, sucrase, trehalase, and others. In humans, about 70 genes are known that code for glycosidases. They have functions in the digestion and degradation of glycogen, sphingolipids, mucopolysaccharides, and poly(ADP-ribose). Humans do not produce cellulases, chitinases, or trehalases, but the bacteria in the gut microbiota do.

In order to get into or out of cell membranes of cells and membranes of cell compartments, glucose requires special transport proteins from the major facilitator superfamily. In the small intestine (more precisely, in the jejunum),[48] glucose is taken up into the intestinal epithelium with the help of glucose transporters[49] via a secondary active transport mechanism called sodium ion-glucose symport via sodium/glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1).[50] Further transfer occurs on the basolateral side of the intestinal epithelial cells via the glucose transporter GLUT2,[50] as well uptake into liver cells, kidney cells, cells of the islets of Langerhans, neurons, astrocytes, and tanycytes.[51] Glucose enters the liver via the portal vein and is stored there as a cellular glycogen.[52] In the liver cell, it is phosphorylated by glucokinase at position 6 to form glucose 6-phosphate, which cannot leave the cell. Glucose 6-phosphatase can convert glucose 6-phosphate back into glucose exclusively in the liver, so the body can maintain a sufficient blood glucose concentration. In other cells, uptake happens by passive transport through one of the 14 GLUT proteins.[50] In the other cell types, phosphorylation occurs through a hexokinase, whereupon glucose can no longer diffuse out of the cell.

The glucose transporter GLUT1 is produced by most cell types and is of particular importance for nerve cells and pancreatic β-cells.[50] GLUT3 is highly expressed in nerve cells.[50] Glucose from the bloodstream is taken up by GLUT4 from muscle cells (of the skeletal muscle[53] and heart muscle) and fat cells.[54] GLUT14 is expressed exclusively in testicles.[55] Excess glucose is broken down and converted into fatty acids, which are stored as triglycerides. In the kidneys, glucose in the urine is absorbed via SGLT1 and SGLT2 in the apical cell membranes and transmitted via GLUT2 in the basolateral cell membranes.[56] About 90% of kidney glucose reabsorption is via SGLT2 and about 3% via SGLT1.[57]

Biosynthesis

In plants and some prokaryotes, glucose is a product of photosynthesis.[58] Glucose is also formed by the breakdown of polymeric forms of glucose like glycogen (in animals and mushrooms) or starch (in plants). The cleavage of glycogen is termed glycogenolysis, the cleavage of starch is called starch degradation.[59]

The metabolic pathway that begins with molecules containing two to four carbon atoms (C) and ends in the glucose molecule containing six carbon atoms is called gluconeogenesis and occurs in all living organisms. The smaller starting materials are the result of other metabolic pathways. Ultimately almost all biomolecules come from the assimilation of carbon dioxide in plants and microbes during photosynthesis.[40]:359 The free energy of formation of α-d-glucose is 917.2 kilojoules per mole.[40]:59 In humans, gluconeogenesis occurs in the liver and kidney,[60] but also in other cell types. In the liver about 150 g (5.3 oz) of glycogen are stored, in skeletal muscle about 250 g (8.8 oz).[61] However, the glucose released in muscle cells upon cleavage of the glycogen can not be delivered to the circulation because glucose is phosphorylated by the hexokinase, and a glucose-6-phosphatase is not expressed to remove the phosphate group. Unlike for glucose, there is no transport protein for glucose-6-phosphate. Gluconeogenesis allows the organism to build up glucose from other metabolites, including lactate or certain amino acids, while consuming energy. The renal tubular cells can also produce glucose.

Glucose also can be found outside of living organisms in the ambient environment. Glucose concentrations in the atmosphere are detected via collection of samples by aircraft and are known to vary from location to location. For example, glucose concentrations in atmospheric air from inland China range from 0.8 to 20.1 pg/L, whereas east coastal China glucose concentrations range from 10.3 to 142 pg/L.[62]

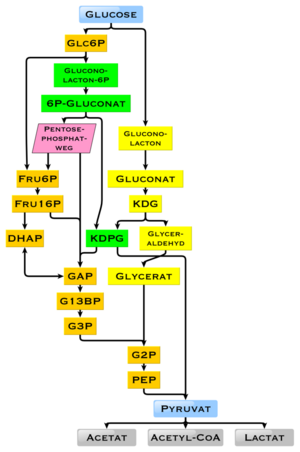

Glucose degradation

In humans, glucose is metabolized by glycolysis[63] and the pentose phosphate pathway.[64] Glycolysis is used by all living organisms,[39]:551[65] with small variations, and all organisms generate energy from the breakdown of monosaccharides.[65] In the further course of the metabolism, it can be completely degraded via oxidative decarboxylation, the citric acid cycle (synonym Krebs cycle) and the respiratory chain to water and carbon dioxide. If there is not enough oxygen available for this, the glucose degradation in animals occurs anaerobic to lactate via lactic acid fermentation and releases much less energy. Muscular lactate enters the liver through the bloodstream in mammals, where gluconeogenesis occurs (Cori cycle). With a high supply of glucose, the metabolite acetyl-CoA from the Krebs cycle can also be used for fatty acid synthesis.[66] Glucose is also used to replenish the body's glycogen stores, which are mainly found in liver and skeletal muscle. These processes are hormonally regulated.

In other living organisms, other forms of fermentation can occur. The bacterium Escherichia coli can grow on nutrient media containing glucose as the sole carbon source.[40]:59 In some bacteria and, in modified form, also in archaea, glucose is degraded via the Entner-Doudoroff pathway.[67]

Use of glucose as an energy source in cells is by either aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration, or fermentation. The first step of glycolysis is the phosphorylation of glucose by a hexokinase to form glucose 6-phosphate. The main reason for the immediate phosphorylation of glucose is to prevent its diffusion out of the cell as the charged phosphate group prevents glucose 6-phosphate from easily crossing the cell membrane.[68] Furthermore, addition of the high-energy phosphate group activates glucose for subsequent breakdown in later steps of glycolysis. At physiological conditions, this initial reaction is irreversible.

In anaerobic respiration, one glucose molecule produces a net gain of two ATP molecules (four ATP molecules are produced during glycolysis through substrate-level phosphorylation, but two are required by enzymes used during the process).[69] In aerobic respiration, a molecule of glucose is much more profitable in that a maximum net production of 30 or 32 ATP molecules (depending on the organism) is generated.[70]

Tumor cells often grow comparatively quickly and consume an above-average amount of glucose by glycolysis,[71] which leads to the formation of lactate, the end product of fermentation in mammals, even in the presence of oxygen. This is called the Warburg effect. For the increased uptake of glucose in tumors various SGLT and GLUT are overly produced.[72][73]

In yeast, ethanol is fermented at high glucose concentrations, even in the presence of oxygen (which normally leads to respiration rather than fermentation). This is called the Crabtree effect.

Glucose can also degrade to form carbon dioxide through abiotic means. This has been demonstrated to occur experimentally via oxidation and hydrolysis at 22 °C and a pH of 2.5.[74]

Energy source

Glucose is a ubiquitous fuel in biology. It is used as an energy source in organisms, from bacteria to humans, through either aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration (in bacteria), or fermentation. Glucose is the human body's key source of energy, through aerobic respiration, providing about 3.75 kilocalories (16 kilojoules) of food energy per gram.[75] Breakdown of carbohydrates (e.g., starch) yields mono- and disaccharides, most of which is glucose. Through glycolysis and later in the reactions of the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, glucose is oxidized to eventually form carbon dioxide and water, yielding energy mostly in the form of ATP. The insulin reaction, and other mechanisms, regulate the concentration of glucose in the blood. The physiological caloric value of glucose, depending on the source, is 16.2 kilojoules per gram[76] or 15.7 kJ/g (3.74 kcal/g).[77] The high availability of carbohydrates from plant biomass has led to a variety of methods during evolution, especially in microorganisms, to utilize glucose for energy and carbon storage. Differences exist in which end product can no longer be used for energy production. The presence of individual genes, and their gene products, the enzymes, determine which reactions are possible. The metabolic pathway of glycolysis is used by almost all living beings. An essential difference in the use of glycolysis is the recovery of NADPH as a reductant for anabolism that would otherwise have to be generated indirectly.[78]

Glucose and oxygen supply almost all the energy for the brain,[79] so its availability influences psychological processes. When glucose is low, psychological processes requiring mental effort (e.g., self-control, effortful decision-making) are impaired.[80][81][82][83] In the brain, which is dependent on glucose and oxygen as the major source of energy, the glucose concentration is usually 4 to 6 mM (5 mM equals 90 mg/dL),[43] but decreases to 2 to 3 mM when fasting.[84] Confusion occurs below 1 mM and coma at lower levels.[84]

The glucose in the blood is called blood sugar. Blood sugar levels are regulated by glucose-binding nerve cells in the hypothalamus.[85] In addition, glucose in the brain binds to glucose receptors of the reward system in the nucleus accumbens.[85] The binding of glucose to the sweet receptor on the tongue induces a release of various hormones of energy metabolism, either through glucose or through other sugars, leading to an increased cellular uptake and lower blood sugar levels.[86] Artificial sweeteners do not lower blood sugar levels.[86]

The blood sugar content of a healthy person in the short-time fasting state, e.g. after overnight fasting, is about 70 to 100 mg/dL of blood (4 to 5.5 mM). In blood plasma, the measured values are about 10–15% higher. In addition, the values in the arterial blood are higher than the concentrations in the venous blood since glucose is absorbed into the tissue during the passage of the capillary bed. Also in the capillary blood, which is often used for blood sugar determination, the values are sometimes higher than in the venous blood. The glucose content of the blood is regulated by the hormones insulin, incretin and glucagon.[85][87] Insulin lowers the glucose level, glucagon increases it.[43] Furthermore, the hormones adrenaline, thyroxine, glucocorticoids, somatotropin and adrenocorticotropin lead to an increase in the glucose level.[43] There is also a hormone-independent regulation, which is referred to as glucose autoregulation.[88] After food intake the blood sugar concentration increases. Values over 180 mg/dL in venous whole blood are pathological and are termed hyperglycemia, values below 40 mg/dL are termed hypoglycaemia.[89] When needed, glucose is released into the bloodstream by glucose-6-phosphatase from glucose-6-phosphate originating from liver and kidney glycogen, thereby regulating the homeostasis of blood glucose concentration.[60][42] In ruminants, the blood glucose concentration is lower (60 mg/dL in cattle and 40 mg/dL in sheep), because the carbohydrates are converted more by their gut microbiota into short-chain fatty acids.[90]

Some glucose is converted to lactic acid by astrocytes, which is then utilized as an energy source by brain cells; some glucose is used by intestinal cells and red blood cells, while the rest reaches the liver, adipose tissue and muscle cells, where it is absorbed and stored as glycogen (under the influence of insulin). Liver cell glycogen can be converted to glucose and returned to the blood when insulin is low or absent; muscle cell glycogen is not returned to the blood because of a lack of enzymes. In fat cells, glucose is used to power reactions that synthesize some fat types and have other purposes. Glycogen is the body's "glucose energy storage" mechanism, because it is much more "space efficient" and less reactive than glucose itself.

As a result of its importance in human health, glucose is an analyte in glucose tests that are common medical blood tests.[91] Eating or fasting prior to taking a blood sample has an effect on analyses for glucose in the blood; a high fasting glucose blood sugar level may be a sign of prediabetes or diabetes mellitus.[92]

The glycemic index is an indicator of the speed of resorption and conversion to blood glucose levels from ingested carbohydrates, measured as the area under the curve of blood glucose levels after consumption in comparison to glucose (glucose is defined as 100).[93] The clinical importance of the glycemic index is controversial,[93][94] as foods with high fat contents slow the resorption of carbohydrates and lower the glycemic index, e.g. ice cream.[94] An alternative indicator is the insulin index,[95] measured as the impact of carbohydrate consumption on the blood insulin levels. The glycemic load is an indicator for the amount of glucose added to blood glucose levels after consumption, based on the glycemic index and the amount of consumed food.

Precursor

Organisms use glucose as a precursor for the synthesis of several important substances. Starch, cellulose, and glycogen ("animal starch") are common glucose polymers (polysaccharides). Some of these polymers (starch or glycogen) serve as energy stores, while others (cellulose and chitin, which is made from a derivative of glucose) have structural roles. Oligosaccharides of glucose combined with other sugars serve as important energy stores. These include lactose, the predominant sugar in milk, which is a glucose-galactose disaccharide, and sucrose, another disaccharide which is composed of glucose and fructose. Glucose is also added onto certain proteins and lipids in a process called glycosylation. This is often critical for their functioning. The enzymes that join glucose to other molecules usually use phosphorylated glucose to power the formation of the new bond by coupling it with the breaking of the glucose-phosphate bond.

Other than its direct use as a monomer, glucose can be broken down to synthesize a wide variety of other biomolecules. This is important, as glucose serves both as a primary store of energy and as a source of organic carbon. Glucose can be broken down and converted into lipids. It is also a precursor for the synthesis of other important molecules such as vitamin C (ascorbic acid). In living organisms, glucose is converted to several other chemical compounds that are the starting material for various metabolic pathways. Among them, all other monosaccharides[96] such as fructose (via the polyol pathway),[50] mannose (the epimer of glucose at position 2), galactose (the epimer at position 4), fucose, various uronic acids and the amino sugars are produced from glucose.[52] In addition to the phosphorylation to glucose-6-phosphate, which is part of the glycolysis, glucose can be oxidized during its degradation to glucono-1,5-lactone. Glucose is used in some bacteria as a building block in the trehalose or the dextran biosynthesis and in animals as a building block of glycogen. Glucose can also be converted from bacterial xylose isomerase to fructose. In addition, glucose metabolites produce all nonessential amino acids, sugar alcohols such as mannitol and sorbitol, fatty acids, cholesterol and nucleic acids.[96] Finally, glucose is used as a building block in the glycosylation of proteins to glycoproteins, glycolipids, peptidoglycans, glycosides and other substances (catalyzed by glycosyltransferases) and can be cleaved from them by glycosidases.

Pathology

Diabetes

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder where the body is unable to regulate levels of glucose in the blood either because of a lack of insulin in the body or the failure, by cells in the body, to respond properly to insulin. Each of these situations can be caused by persistently high elevations of blood glucose levels, through pancreatic burnout and insulin resistance. The pancreas is the organ responsible for the secretion of the hormones insulin and glucagon.[97] Insulin is a hormone that regulates glucose levels, allowing the body's cells to absorb and use glucose. Without it, glucose cannot enter the cell and therefore cannot be used as fuel for the body's functions.[98] If the pancreas is exposed to persistently high elevations of blood glucose levels, the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas could be damaged, causing a lack of insulin in the body. Insulin resistance occurs when the pancreas tries to produce more and more insulin in response to persistently elevated blood glucose levels. Eventually, the rest of the body becomes resistant to the insulin that the pancreas is producing, thereby requiring more insulin to achieve the same blood glucose-lowering effect, and forcing the pancreas to produce even more insulin to compete with the resistance. This negative spiral contributes to pancreatic burnout, and the disease progression of diabetes.

To monitor the body's response to blood glucose-lowering therapy, glucose levels can be measured. Blood glucose monitoring can be performed by multiple methods, such as the fasting glucose test which measures the level of glucose in the blood after 8 hours of fasting. Another test is the 2-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) – for this test, the person has a fasting glucose test done, then drinks a 75-gram glucose drink and is retested. This test measures the ability of the person's body to process glucose. Over time the blood glucose levels should decrease as insulin allows it to be taken up by cells and exit the blood stream.

Hypoglycemia management

Individuals with diabetes or other conditions that result in low blood sugar often carry small amounts of sugar in various forms. One sugar commonly used is glucose, often in the form of glucose tablets (glucose pressed into a tablet shape sometimes with one or more other ingredients as a binder), hard candy, or sugar packet.

Sources

Most dietary carbohydrates contain glucose, either as their only building block (as in the polysaccharides starch and glycogen), or together with another monosaccharide (as in the hetero-polysaccharides sucrose and lactose).[99] Unbound glucose is one of the main ingredients of honey. Glucose is extremely abundant and has been isolated from a variety of natural sources across the world, including male cones of the coniferous tree Wollemia nobilis in Rome,[100] the roots of Ilex asprella plants in China,[101] and straws from rice in California.[102]

| Food item |

Carbohydrate, total,[lower-alpha 1] including dietary fiber |

Total sugars |

Free fructose |

Free glucose |

Sucrose | Ratio of fructose/ glucose |

Sucrose as proportion of total sugars (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | |||||||

| Apple | 13.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 19.9 |

| Apricot | 11.1 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 63.5 |

| Banana | 22.8 | 12.2 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 20.0 |

| Fig, dried | 63.9 | 47.9 | 22.9 | 24.8 | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.15 |

| Grapes | 18.1 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Navel orange | 12.5 | 8.5 | 2.25 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 50.4 |

| Peach | 9.5 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 56.7 |

| Pear | 15.5 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 8.0 |

| Pineapple | 13.1 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 60.8 |

| Plum | 11.4 | 9.9 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 0.66 | 16.2 |

| Vegetables | |||||||

| Beet, red | 9.6 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 96.2 |

| Carrot | 9.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 77 |

| Red pepper, sweet | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Onion, sweet | 7.6 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 14.3 |

| Sweet potato | 20.1 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 60.3 |

| Yam | 27.9 | 0.5 | Traces | Traces | Traces | N/A | Traces |

| Sugar cane | 13–18 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–1.0 | 11–16 | 1.0 | high | |

| Sugar beet | 17–18 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1–0.5 | 16–17 | 1.0 | high | |

| Grains | |||||||

| Corn, sweet | 19.0 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.61 | 15.0 |

- ↑ The carbohydrate value is calculated in the USDA database and does not always correspond to the sum of the sugars, the starch, and the "dietary fiber".

Commercial production

Glucose is produced industrially from starch by enzymatic hydrolysis using glucose amylase or by the use of acids. Enzymatic hydrolysis has largely displaced acid-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions.[104] The result is glucose syrup (enzymatically with more than 90% glucose in the dry matter)[104] with an annual worldwide production volume of 20 million tonnes (as of 2011).[105] This is the reason for the former common name "starch sugar". The amylases most often come from Bacillus licheniformis[106] or Bacillus subtilis (strain MN-385),[106] which are more thermostable than the originally used enzymes.[106][107] Starting in 1982, pullulanases from Aspergillus niger were used in the production of glucose syrup to convert amylopectin to starch (amylose), thereby increasing the yield of glucose.[108] The reaction is carried out at a pH = 4.6–5.2 and a temperature of 55–60 °C.[10] Corn syrup has between 20% and 95% glucose in the dry matter.[109][110] The Japanese form of the glucose syrup, Mizuame, is made from sweet potato or rice starch.[111] Maltodextrin contains about 20% glucose.

Many crops can be used as the source of starch. Maize,[104] rice,[104] wheat,[104] cassava,[104] potato,[104] barley,[104] sweet potato,[112] corn husk and sago are all used in various parts of the world. In the United States , corn starch (from maize) is used almost exclusively. Some commercial glucose occurs as a component of invert sugar, a roughly 1:1 mixture of glucose and fructose that is produced from sucrose. In principle, cellulose could be hydrolyzed to glucose, but this process is not yet commercially practical.[27]

Conversion to fructose

In the US, almost exclusively corn (more precisely, corn syrup) is used as glucose source for the production of isoglucose, which is a mixture of glucose and fructose, since fructose has a higher sweetening power – with same physiological calorific value of 374 kilocalories per 100 g. The annual world production of isoglucose is 8 million tonnes (as of 2011).[105] When made from corn syrup, the final product is high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

Commercial usage

Glucose is mainly used for the production of fructose and of glucose-containing foods. In foods, it is used as a sweetener, humectant, to increase the volume and to create a softer mouthfeel.[104] Various sources of glucose, such as grape juice (for wine) or malt (for beer), are used for fermentation to ethanol during the production of alcoholic beverages. Most soft drinks in the US use HFCS-55 (with a fructose content of 55% in the dry mass), while most other HFCS-sweetened foods in the US use HFCS-42 (with a fructose content of 42% in the dry mass).[114] In Mexico, on the other hand, soft drinks are sweetened by cane sugar, which has a higher sweetening power.[115] In addition, glucose syrup is used, inter alia, in the production of confectionery such as candies, toffee and fondant.[116] Typical chemical reactions of glucose when heated under water-free conditions are caramelization and, in presence of amino acids, the Maillard reaction.

In addition, various organic acids can be biotechnologically produced from glucose, for example by fermentation with Clostridium thermoaceticum to produce acetic acid, with Penicillium notatum for the production of araboascorbic acid, with Rhizopus delemar for the production of fumaric acid, with Aspergillus niger for the production of gluconic acid, with Candida brumptii to produce isocitric acid, with Aspergillus terreus for the production of itaconic acid, with Pseudomonas fluorescens for the production of 2-ketogluconic acid, with Gluconobacter suboxydans for the production of 5-ketogluconic acid, with Aspergillus oryzae for the production of kojic acid, with Lactobacillus delbrueckii for the production of lactic acid, with Lactobacillus brevis for the production of malic acid, with Propionibacter shermanii for the production of propionic acid, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa for the production of pyruvic acid and with Gluconobacter suboxydans for the production of tartaric acid.[117][additional citation(s) needed] Potent, bioactive natural products like triptolide that inhibit mammalian transcription via inhibition of the XPB subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIH has been recently reported as a glucose conjugate for targeting hypoxic cancer cells with increased glucose transporter expression.[118] Recently, glucose has been gaining commercial use as a key component of "kits" containing lactic acid and insulin intended to induce hypoglycemia and hyperlactatemia to combat different cancers and infections.[119]

Analysis

When a glucose molecule is to be detected at a certain position in a larger molecule, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography analysis or lectin immunostaining is performed with concanavalin A reporter enzyme conjugate, which binds only glucose or mannose.

Classical qualitative detection reactions

These reactions have only historical significance:

Fehling test

The Fehling test is a classic method for the detection of aldoses.[120] Due to mutarotation, glucose is always present to a small extent as an open-chain aldehyde. By adding the Fehling reagents (Fehling (I) solution and Fehling (II) solution), the aldehyde group is oxidized to a carboxylic acid, while the Cu2+ tartrate complex is reduced to Cu+ and forms a brick red precipitate (Cu2O).

Tollens test

In the Tollens test, after addition of ammoniacal AgNO3 to the sample solution, glucose reduces Ag+ to elemental silver.[121]

Barfoed test

In Barfoed's test,[122] a solution of dissolved copper acetate, sodium acetate and acetic acid is added to the solution of the sugar to be tested and subsequently heated in a water bath for a few minutes. Glucose and other monosaccharides rapidly produce a reddish color and reddish brown copper(I) oxide (Cu2O).

Nylander's test

As a reducing sugar, glucose reacts in the Nylander's test.[123]

Other tests

Upon heating a dilute potassium hydroxide solution with glucose to 100 °C, a strong reddish browning and a caramel-like odor develops.[124] Concentrated sulfuric acid dissolves dry glucose without blackening at room temperature forming sugar sulfuric acid.[124][verification needed] In a yeast solution, alcoholic fermentation produces carbon dioxide in the ratio of 2.0454 molecules of glucose to one molecule of CO2.[124] Glucose forms a black mass with stannous chloride.[124] In an ammoniacal silver solution, glucose (as well as lactose and dextrin) leads to the deposition of silver. In an ammoniacal lead acetate solution, white lead glycoside is formed in the presence of glucose, which becomes less soluble on cooking and turns brown.[124] In an ammoniacal copper solution, yellow copper oxide hydrate is formed with glucose at room temperature, while red copper oxide is formed during boiling (same with dextrin, except for with an ammoniacal copper acetate solution).[124] With Hager's reagent, glucose forms mercury oxide during boiling.[124] An alkaline bismuth solution is used to precipitate elemental, black-brown bismuth with glucose.[124] Glucose boiled in an ammonium molybdate solution turns the solution blue. A solution with indigo carmine and sodium carbonate destains when boiled with glucose.[124]

Instrumental quantification

Refractometry and polarimetry

In concentrated solutions of glucose with a low proportion of other carbohydrates, its concentration can be determined with a polarimeter. For sugar mixtures, the concentration can be determined with a refractometer, for example in the Oechsle determination in the course of the production of wine.

Photometric enzymatic methods in solution

The enzyme glucose oxidase (GOx) converts glucose into gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide while consuming oxygen. Another enzyme, peroxidase, catalyzes a chromogenic reaction (Trinder reaction)[125] of phenol with 4-aminoantipyrine to a purple dye.

Photometric test-strip method

The test-strip method employs the above-mentioned enzymatic conversion of glucose to gluconic acid to form hydrogen peroxide. The reagents are immobilised on a polymer matrix, the so-called test strip, which assumes a more or less intense color. This can be measured reflectometrically at 510 nm with the aid of an LED-based handheld photometer. This allows routine blood sugar determination by nonscientists. In addition to the reaction of phenol with 4-aminoantipyrine, new chromogenic reactions have been developed that allow photometry at higher wavelengths (550 nm, 750 nm).[126]

Amperometric glucose sensor

The electroanalysis of glucose is also based on the enzymatic reaction mentioned above. The produced hydrogen peroxide can be amperometrically quantified by anodic oxidation at a potential of 600 mV.[127] The GOx is immobilized on the electrode surface or in a membrane placed close to the electrode. Precious metals such as platinum or gold are used in electrodes, as well as carbon nanotube electrodes, which e.g. are doped with boron.[128] Cu–CuO nanowires are also used as enzyme-free amperometric electrodes, reaching a detection limit of 50 μmol/L.[129] A particularly promising method is the so-called "enzyme wiring", where the electron flowing during the oxidation is transferred via a molecular wire directly from the enzyme to the electrode.[130]

Other sensory methods

There are a variety of other chemical sensors for measuring glucose.[131][132] Given the importance of glucose analysis in the life sciences, numerous optical probes have also been developed for saccharides based on the use of boronic acids,[133] which are particularly useful for intracellular sensory applications where other (optical) methods are not or only conditionally usable. In addition to the organic boronic acid derivatives, which often bind highly specifically to the 1,2-diol groups of sugars, there are also other probe concepts classified by functional mechanisms which use selective glucose-binding proteins (e.g. concanavalin A) as a receptor. Furthermore, methods were developed which indirectly detect the glucose concentration via the concentration of metabolized products, e.g. by the consumption of oxygen using fluorescence-optical sensors.[134] Finally, there are enzyme-based concepts that use the intrinsic absorbance or fluorescence of (fluorescence-labeled) enzymes as reporters.[131]

Copper iodometry

Glucose can be quantified by copper iodometry.[135]

Chromatographic methods

In particular, for the analysis of complex mixtures containing glucose, e.g. in honey, chromatographic methods such as high performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography[135] are often used in combination with mass spectrometry.[136][137] Taking into account the isotope ratios, it is also possible to reliably detect honey adulteration by added sugars with these methods.[138] Derivatization using silylation reagents is commonly used.[139] Also, the proportions of di- and trisaccharides can be quantified.

In vivo analysis

Glucose uptake in cells of organisms is measured with 2-deoxy-D-glucose or fluorodeoxyglucose.[84] (18F)fluorodeoxyglucose is used as a tracer in positron emission tomography in oncology and neurology,[140] where it is by far the most commonly used diagnostic agent.[141]

References

- ↑ Nomenclature of Carbohydrates (Recommendations 1996) | 2-Carb-2. iupac.qmul.ac.uk.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Boerio-Goates, Juliana (1991), "Heat-capacity measurements and thermodynamic functions of crystalline α-D-glucose at temperatures from 10K to 340K", J. Chem. Thermodyn. 23 (5): 403–09, doi:10.1016/S0021-9614(05)80128-4

- ↑ Ponomarev, V. V.; Migarskaya, L. B. (1960), "Heats of combustion of some amino-acids", Russ. J. Phys. Chem. (Engl. Transl.) 34: 1182–83

- ↑ Domb, Abraham J.; Kost, Joseph; Wiseman, David (1998-02-04). Handbook of Biodegradable Polymers. CRC Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-4200-4936-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=iLjhl6AvfIsC&pg=PA275.

- ↑ Kamide, Kenji (2005). Cellulose products and Cellulose Derivatives: Molecular Characterization and its Applications (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 9780080454443. https://books.google.com/books?id=28Vx9OkEtQcC&pg=PA1. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ "L-glucose" (in en-US). 2019-10-07. https://www.biologyonline.com/dictionary/l-glucose.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=glucose.

- ↑ Thénard, Gay-Lussac, Biot, and Dumas (1838) "Rapport sur un mémoire de M. Péligiot, intitulé: Recherches sur la nature et les propriétés chimiques des sucres". (Report on a memoir of Mr. Péligiot, titled: Investigations on the nature and chemical properties of sugars), Comptes rendus, 7 : 106–113. From page 109. : "Il résulte des comparaisons faites par M. Péligot, que le sucre de raisin, celui d'amidon, celui de diabètes et celui de miel ont parfaitement la même composition et les mêmes propriétés, et constituent un seul corps que nous proposons d'appeler Glucose (1). ... (1) γλευχος, moût, vin doux." It follows from the comparisons made by Mr. Péligot, that the sugar from grapes, that from starch, that from diabetes and that from honey have exactly the same composition and the same properties, and constitute a single substance that we propose to call glucose (1) ... (1) γλευχος, must, sweet wine.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 (in en) Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Academic Press. 2015. p. 239. ISBN 9780123849533. https://books.google.com/books?id=O-t9BAAAQBAJ&pg=RA2-PA239.

- ↑ Marggraf (1747) "Experiences chimiques faites dans le dessein de tirer un veritable sucre de diverses plantes, qui croissent dans nos contrées" [Chemical experiments made with the intention of extracting real sugar from diverse plants that grow in our lands], Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Berlin, pp. 79–90. From page 90: "Les raisins secs, etant humectés d'une petite quantité d'eau, de maniere qu'ils mollissent, peuvent alors etre pilés, & le suc qu'on en exprime, etant depuré & épaissi, fournira une espece de Sucre." (Raisins, being moistened with a small quantity of water, in a way that they soften, can be then pressed, and the juice that is squeezed out, [after] being purified and thickened, will provide a sort of sugar.)

- ↑ John F. Robyt: Essentials of Carbohydrate Chemistry. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, ISBN:978-1-461-21622-3. p. 7.

- ↑ Rosanoff, M. A. (1906). "On Fischer's Classification of Stereo-Isomers.1". Journal of the American Chemical Society 28: 114–121. doi:10.1021/ja01967a014. https://zenodo.org/record/1428874.

- ↑ Emil Fischer, Nobel Foundation, http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1902/fischer-bio.html, retrieved 2009-09-02

- ↑ Fraser-Reid, Bert, "van't Hoff's Glucose", Chem. Eng. News 77 (39): 8

- ↑ "Otto Meyerhof - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Hans von Euler-Chelpin - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Arthur Harden - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Bernardo Houssay - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Carl Cori - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Gerty Cori - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Luis Leloir - Facts - NobelPrize.org" . NobelPrize.org. Retrieved on 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Wenyue Kang and Zhijun Zhang (2020): "Selective Production of Acetic Acid via Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Hexoses over Potassium Salts", Catalysts, volume 10, pages 502–515. doi:10.3390/catal10050502

- ↑ Bosch, L.I.; Fyles, T.M.; James, T.D. (2004). "Binary and ternary phenylboronic acid complexes with saccharides and Lewis bases". Tetrahedron 60 (49): 11175–11190. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.08.046. ISSN 0040-4020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2004.08.046.

- ↑ Yebra-Biurrun, M.C. (2005) (in en), Sweeteners, Elsevier, pp. 562–572, doi:10.1016/b0-12-369397-7/00610-5, ISBN 978-0-12-369397-6

- ↑ "glucose." The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.. 2015. Encyclopedia.com. 17 Nov. 2015 http://www.encyclopedia.com .

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Schenck, Fred W. (2006). "Glucose and Glucose-Containing Syrups". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_457.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ↑ Patrick F. Fox: Advanced Dairy Chemistry Volume 3: Lactose, water, salts and vitamins, Springer, 1992. Volume 3, ISBN:9780412630200. p. 316.

- ↑ Benjamin Caballero, Paul Finglas, Fidel Toldrá: Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Academic Press (2016). ISBN:9780123849533, Volume 1, p. 76.

- ↑ "16.4: Cyclic Structures of Monosaccharides" (in en). 2014-07-18. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_Chemistry/Basics_of_General_Organic_and_Biological_Chemistry_(Ball_et_al.)/16%3A_Carbohydrates/16.04%3A_Cyclic_Structures_of_Monosaccharides.

- ↑ Takagi, S.; Jeffrey, G. A. (1979). "1,2-O-isopropylidene-D-glucofuranose". Acta Crystallographica Section B B35 (6): 1522–1525. doi:10.1107/S0567740879006968. Bibcode: 1979AcCrB..35.1522T.

- ↑ Bielecki, Mia; Eggert, Hanne; Christian Norrild, Jens (1999). "A fluorescent glucose sensor binding covalently to all five hydroxy groups of α-D-glucofuranose. A reinvestigation". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 (3): 449–456. doi:10.1039/A808896I.

- ↑ Chandran, Sreekanth K.; Nangia, Ashwini (2006). "Modulated crystal structure (Z′ = 2) of α-d-glucofuranose-1,2:3,5-bis(p-tolyl)boronate". CrystEngComm 8 (8): 581–585. doi:10.1039/B608029D.

- ↑ Template:McMurry2nd.

- ↑ Juaristi, Eusebio; Cuevas, Gabriel (1995), The Anomeric Effect, CRC Press, pp. 9–10, ISBN 978-0-8493-8941-2

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Manfred Hesse, Herbert Meier, Bernd Zeeh, Stefan Bienz, Laurent Bigler, Thomas Fox: Spektroskopische Methoden in der organischen Chemie. 8th revised Edition. Georg Thieme, 2011, ISBN:978-3-13-160038-7, p. 34 (in German).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Bunn, H. F.; Higgins, P. J. (1981). "Reaction of monosaccharides with proteins: possible evolutionary significance". Science 213 (4504): 222–24. doi:10.1126/science.12192669. PMID 12192669. Bibcode: 1981Sci...213..222B.

- ↑ Jeremy M. Berg: Stryer Biochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2017, ISBN:978-3-662-54620-8, p. 531. (german)

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Garrett, Reginald H. (2013). Biochemistry (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-133-10629-6.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Voet, Donald; Voet, Judith G. (2011). Biochemistry (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470-57095-1.

- ↑ Albert L. Lehninger, Biochemistry, 6th printing, Worth Publishers Inc. 1972, ISBN:0-87901-009-6 p. 228.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Peter C. Heinrich: Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2014, ISBN:978-3-642-17972-3, p. 195. (german)

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 U. Satyanarayana: Biochemistry. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014, ISBN:978-8-131-23713-7. p. 674.

- ↑ Wasserman, D. H. (2009). "Four grams of glucose". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 296 (1): E11–21. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90563.2008. PMID 18840763.

- ↑ "High Blood Glucose and Diabetes Complications: The buildup of molecules known as AGEs may be the key link", Diabetes Forecast (American Diabetes Association), 2010, ISSN 0095-8301, http://forecast.diabetes.org/magazine/features/high-blood-glucose-and-diabetes-complications, retrieved 2010-05-20

- ↑ Varki, A.; Cummings, R. D.; Esko, J. D.; Freeze, H. H.; Stanley, P.; Bertozzi, C. R.; Hart, G. W.; Etzler, M. E. (2009). Varki, Ajit. ed. Essentials of Glycobiology (2nd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-770-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1908/.

- ↑ Peter C. Heinrich: Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2014, ISBN:978-3-642-17972-3, p. 404.

- ↑ Harold A. Harper: Medizinische Biochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN:978-3-662-22150-1, p. 641. (in German)

- ↑ Navale, A. M.; Paranjape, A. N. (2016). "Glucose transporters: Physiological and pathological roles". Biophysical Reviews 8 (1): 5–9. doi:10.1007/s12551-015-0186-2. PMID 28510148.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 Peter C. Heinrich: Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2014, ISBN:978-3-642-17972-3, p. 199, 200. (in German)

- ↑ Thorens, B. (2015). "GLUT2, glucose sensing and glucose homeostasis". Diabetologia 58 (2): 221–32. doi:10.1007/s00125-014-3451-1. PMID 25421524.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Peter C. Heinrich: Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2014, ISBN:978-3-642-17972-3, p. 214. (in German)

- ↑ Huang, S.; Czech, M. P. (2007). "The GLUT4 glucose transporter". Cell Metabolism 5 (4): 237–52. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.006. PMID 17403369.

- ↑ Govers, R. (2014). Cellular regulation of glucose uptake by glucose transporter GLUT4. 66. 173–240. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801401-1.00006-2. ISBN 9780128014011.

- ↑ Wu, Xiaohua; Freeze, Hudson H. (December 2002). "GLUT14, a Duplicon of GLUT3, is Specifically Expressed in Testis as Alternative Splice Forms". Genomics 80 (6): 553–7. doi:10.1006/geno.2002.7010. PMID 12504846.

- ↑ Ghezzi, C.; Loo DDF; Wright, E. M. (2018). "Physiology of renal glucose handling via SGLT1, SGLT2, and GLUT2". Diabetologia 61 (10): 2087–2097. doi:10.1007/s00125-018-4656-5. PMID 30132032.

- ↑ Poulsen, S. B.; Fenton, R. A.; Rieg, T. (2015). "Sodium-glucose cotransport". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension 24 (5): 463–9. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000152. PMID 26125647.

- ↑ "Chemistry for Biologists: Photosynthesis". http://www.rsc.org/Education/Teachers/Resources/cfb/Photosynthesis.htm.

- ↑ Smith, Alison M.; Zeeman, Samuel C.; Smith, Steven M. (2005). "Starch Degradation". Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56: 73–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144257. PMID 15862090.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Leszek Szablewski: Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Resistance. Bentham Science Publishers, 2011, ISBN:978-1-608-05189-2, p. 46.

- ↑ Peter C. Heinrich: Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2014, ISBN:978-3-642-17972-3, p. 389. (in German)

- ↑ Wang, Gehui; Kawamura, Kimitaka; Hatakeyama, Shiro; Takami, Akinori; Li, Hong; Wang, Wei (2007-04-04). "Aircraft Measurement of Organic Aerosols over China". Environmental Science & Technology 41 (9): 3115–3120. doi:10.1021/es062601h. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 17539513. Bibcode: 2007EnST...41.3115W. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/es062601h.

- ↑ Adeva-Andany, M. M.; Pérez-Felpete, N.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Donapetry-García, C.; Pazos-García, C. (2016). "Liver glucose metabolism in humans". Bioscience Reports 36 (6): e00416. doi:10.1042/BSR20160385. PMID 27707936.

- ↑ H. Robert Horton, Laurence A. Moran, K. Gray Scrimgeour, Marc D. Perry, J. David Rawn: Biochemie. Pearson Studium; 4. aktualisierte Auflage 2008; ISBN:978-3-8273-7312-0; p. 490–496. (german)

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Brian K. Hall: Strickberger's Evolution. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2013, ISBN:978-1-449-61484-3, p. 164.

- ↑ Jones, J. G. (2016). "Hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism". Diabetologia 59 (6): 1098–103. doi:10.1007/s00125-016-3940-5. PMID 27048250.

- ↑ Entner, N.; Doudoroff, M. (1952). "Glucose and gluconic acid oxidation of Pseudomonas saccharophila". J Biol Chem 196 (2): 853–862. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52415-2. PMID 12981024.

- ↑ Bonadonna, Riccardo C; Bonora, Enzo; Del Prato, Stefano; Saccomani, Maria; Cobelli, Claudio; Natali, Andrea; Frascerra, Silvia; Pecori, Neda et al. (July 1996). "Roles of glucose transport and glucose phosphorylation in muscle insulin resistance of NIDDM". Diabetes 45 (7): 915–25. doi:10.2337/diab.45.7.915. PMID 8666143. http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/45/7/915.full-text.pdf. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ↑ Medical Biochemistry at a Glance @Google books, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, p. 52, ISBN 978-1-4051-1322-9, https://books.google.com/books?id=9BtxCWxrWRoC&pg=PA52

- ↑ Medical Biochemistry at a Glance @Google books, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, p. 50, ISBN 978-1-4051-1322-9, https://books.google.com/books?id=9BtxCWxrWRoC&pg=PA50

- ↑ Annibaldi, A.; Widmann, C. (2010). "Glucose metabolism in cancer cells". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 13 (4): 466–70. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833a5577. PMID 20473153.

- ↑ Szablewski, L. (2013). "Expression of glucose transporters in cancers". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1835 (2): 164–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.12.004. PMID 23266512.

- ↑ Adekola, K.; Rosen, S. T.; Shanmugam, M. (2012). "Glucose transporters in cancer metabolism". Current Opinion in Oncology 24 (6): 650–4. doi:10.1097/CCO.0b013e328356da72. PMID 22913968.

- ↑ Schümann, U.; Gründler, P. (1998). "Electrochemical degradation of organic substances at PbO2 anodes: Monitoring by continuous CO2 measurements". Water Research 32 (9): 2835–2842. doi:10.1016/s0043-1354(98)00046-3. ISSN 0043-1354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0043-1354(98)00046-3.

- ↑ "Chapter 3: Calculation of the Energy Content of Foods – Energy Conversion Factors", Food energy – methods of analysis and conversion factors, FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 77, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2003, ISBN 978-92-5-105014-9, http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/Y5022E/y5022e04.htm

- ↑ Georg Schwedt: Zuckersüße Chemie. John Wiley & Sons, 2012, ISBN:978-3-527-66001-8, p. 100 (in German).

- ↑ Schmidt, Lang: Physiologie des Menschen, 30. Auflage. Springer Verlag, 2007, p. 907 (in German).

- ↑ Dandekar, T.; Schuster, S.; Snel, B.; Huynen, M.; Bork, P. (1999). "Pathway alignment: Application to the comparative analysis of glycolytic enzymes". The Biochemical Journal 343 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1042/bj3430115. PMID 10493919.

- ↑ Dash, Pramod. "Blood Brain Barrier and Cerebral Metabolism (Section 4, Chapter 11)". Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences. Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy – The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. http://neuroscience.uth.tmc.edu/s4/chapter11.html.

- ↑ Fairclough, Stephen H.; Houston, Kim (2004), "A metabolic measure of mental effort", Biol. Psychol. 66 (2): 177–190, doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001, PMID 15041139

- ↑ Gailliot, Matthew T.; Baumeister, Roy F.; DeWall, C. Nathan; Plant, E. Ashby; Brewer, Lauren E.; Schmeichel, Brandon J.; Tice, Dianne M.; Maner, Jon K. (2007), "Self-Control Relies on Glucose as a Limited Energy Source: Willpower is More than a Metaphor", J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92 (2): 325–336, doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325, PMID 17279852, http://www.uky.edu/~njdewa2/gailliotetal07JPSP.pdf

- ↑ Gailliot, Matthew T.; Baumeister, Roy F. (2007), "The Physiology of Willpower: Linking Blood Glucose to Self-Control", Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11 (4): 303–327, doi:10.1177/1088868307303030, PMID 18453466

- ↑ Masicampo, E. J.; Baumeister, Roy F. (2008), "Toward a Physiology of Dual-Process Reasoning and Judgment: Lemonade, Willpower, and Expensive Rule-Based Analysis", Psychol. Sci. 19 (3): 255–60, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02077.x, PMID 18315798

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Donard Dwyer: Glucose Metabolism in the Brain. Academic Press, 2002, ISBN:978-0-123-66852-3, p. XIII.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 Koekkoek, L. L.; Mul, J. D.; La Fleur, S. E. (2017). "Glucose-Sensing in the Reward System". Frontiers in Neuroscience 11: 716. doi:10.3389/fnins.2017.00716. PMID 29311793.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Tucker, R. M.; Tan, S. Y. (2017). "Do non-nutritive sweeteners influence acute glucose homeostasis in humans? A systematic review". Physiology & Behavior 182: 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.09.016. PMID 28939430. https://ap01.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/delivery/61USOUTHAUS_INST/12149779800001831.

- ↑ La Fleur, S. E.; Fliers, E.; Kalsbeek, A. (2014). "Neuroscience of glucose homeostasis". Diabetes and the Nervous System. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 126. pp. 341–351. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53480-4.00026-6. ISBN 9780444534804..

- ↑ Bisschop, P. H.; Fliers, E.; Kalsbeek, A. (2015). "Autonomic regulation of hepatic glucose production". Comprehensive Physiology 5 (1): 147–165. doi:10.1002/cphy.c140009. PMID 25589267.

- ↑ W. A. Scherbaum, B. M. Lobnig, In: Hans-Peter Wolff, Thomas R. Weihrauch: Internistische Therapie 2006, 2007. 16th Edition. Elsevier, 2006, ISBN:3-437-23182-0, p. 927, 985 (in German).

- ↑ Harold A. Harper: Medizinische Biochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN:978-3-662-22150-1, p. 294.

- ↑ Clarke, S. F.; Foster, J. R. (2012). "A history of blood glucose meters and their role in self-monitoring of diabetes mellitus". British Journal of Biomedical Science 69 (2): 83–93. doi:10.1080/09674845.2012.12002443. PMID 22872934.

- ↑ "Diagnosing Diabetes and Learning About Prediabetes" (in en). http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/diagnosis/.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Richard A. Harvey, Denise R. Ferrier: Biochemistry. 5th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, ISBN:978-1-608-31412-6, p. 366.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 U Satyanarayana: Biochemistry. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014, ISBN:978-8-131-23713-7, p. 508.

- ↑ Holt, S. H.; Miller, J. C.; Petocz, P. (1997). "An insulin index of foods: The insulin demand generated by 1000-kJ portions of common foods". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 66 (5): 1264–1276. doi:10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1264. PMID 9356547.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Peter C. Heinrich: Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. Springer-Verlag, 2014, ISBN:978-3-642-17972-3, p. 27. (in German)

- ↑ "Pancreatic Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis". Exp. Mol. Med. 48 (3, March): e219–. 2016. doi:10.1038/emm.2016.6. PMID 26964835.

- ↑ Estela, Carlos (2011) "Blood Glucose Levels," Undergraduate Journal of Mathematical Modeling: One + Two: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 12.

- ↑ "Carbohydrates and Blood Sugar" (in en-US). The Nutrition Source. 2013-08-05. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/carbohydrates/carbohydrates-and-blood-sugar/.

- ↑ Venditti, Alessandro; Frezza, Claudio; Vincenti, Flaminia; Brodella, Antonia; Sciubba, Fabio; Montesano, Camilla; Franceschin, Marco; Sergi, Manuel et al. (2019). "A syn-ent-labdadiene derivative with a rare spiro-β-lactone function from the male cones of Wollemia nobilis". Phytochemistry 158: 91–95. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.11.012. ISSN 0031-9422. PMID 30481664. Bibcode: 2019PChem.158...91V. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.11.012.

- ↑ Lei, Yu; Shi, She-Po; Song, Yue-Lin; Bi, Dan; Tu, Peng-Fei (2014). "Triterpene Saponins from the Roots of Ilex asprella". Chemistry & Biodiversity 11 (5): 767–775. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201300155. ISSN 1612-1872. PMID 24827686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.201300155.

- ↑ Balan, Venkatesh; Bals, Bryan; Chundawat, Shishir P. S.; Marshall, Derek; Dale, Bruce E. (2009), "Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Using AFEX", Biofuels, Methods in Molecular Biology, 581, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, pp. 61–77, doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-214-8_5, ISBN 978-1-60761-213-1, PMID 19768616, Bibcode: 2009biof.book...61B, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-214-8_5, retrieved 2021-11-11

- ↑ "FoodData Central". https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 104.3 104.4 104.5 104.6 104.7 104.8 P. J. Fellows: Food Processing Technology. Woodhead Publishing, 2016, ISBN:978-0-081-00523-1, p. 197.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Thomas Becker, Dietmar Breithaupt, Horst Werner Doelle, Armin Fiechter, Günther Schlegel, Sakayu Shimizu, Hideaki Yamada: Biotechnology, in: Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 7th Edition, Wiley-VCH, 2011. ISBN:978-3-527-32943-4. Volume 6, p. 48.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 The Amylase Research Society of Japan: Handbook of Amylases and Related Enzymes. Elsevier, 2014, ISBN:978-1-483-29939-6, p. 195.

- ↑ Madsen, G. B.; Norman, B. E.; Slott, S. (1973). "A New, Heat Stable Bacterial Amylase and its Use in High Temperature Liquefaction". Starch – Stärke 25 (9): 304–308. doi:10.1002/star.19730250906.

- ↑ Norman, B. E. (1982). "A Novel Debranching Enzyme for Application in the Glucose Syrup Industry". Starch – Stärke 34 (10): 340–346. doi:10.1002/star.19820341005.

- ↑ James N. BeMiller, Roy L. Whistler (2009). Starch: Chemistry and Technology. Food Science and Technology (3rd ed.). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0080926551. https://books.google.com/books?isbn=008092655X.

- ↑ BeMiller, James N., ed (2009). Starch: Chemistry and Technology. Food Science and Technology (3rd ed.). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0080926551. https://books.google.com/books?isbn=008092655X. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ Alan Davidson: Oxford Companion to Food (1999). "Mizuame", p. 510 ISBN:0-19-211579-0.

- ↑ Alan Davidson: The Oxford Companion to Food. OUP Oxford, 2014, ISBN:978-0-191-04072-6, p. 527.

- ↑ "Sugar". Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 2012-05-23. http://food.oregonstate.edu/learn/sugar.html.

- ↑ "High Fructose Corn Syrup: Questions and Answers". US Food and Drug Administration. 2014-11-05. https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/FoodAdditivesIngredients/ucm324856.htm.

- ↑ Kevin Pang: Mexican Coke a hit in U.S. In: Seattle Times, October 29, 2004.

- ↑ Steve T. Beckett: Beckett's Industrial Chocolate Manufacture and Use. John Wiley & Sons, 2017, ISBN:978-1-118-78014-5, p. 82.

- ↑ James A. Kent: Riegel's Handbook of Industrial Chemistry. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013, ISBN:978-1-475-76431-4, p. 938.

- ↑ "A Glucose-Triptolide Conjugate Selectively Targets Cancer Cells under Hypoxia". iScience 23 (9): 101536. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101536. PMID 33083765. Bibcode: 2020iSci...23j1536D.

- ↑ Goodwin, Matthew L.; Gladden, L. Bruce; Nijsten, Maarten W. N. (2020-09-03). "Lactate-Protected Hypoglycemia (LPH)". Frontiers in Neuroscience 14: 920. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00920. ISSN 1662-453X. PMID 33013305.

- ↑ H. Fehling: Quantitative Bestimmung des Zuckers im Harn. In: Archiv für physiologische Heilkunde (1848), volume 7, p. 64–73 (in German).

- ↑ B. Tollens: Über ammon-alkalische Silberlösung als Reagens auf Aldehyd. In Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (1882), volume 15, p. 1635–1639 (in German).

- ↑ Barfoed, C. (1873). "Ueber die Nachweisung des Traubenzuckers neben Dextrin und verwandten Körpern" (in de). Zeitschrift für Analytische Chemie 12: 27–32. doi:10.1007/BF01462957. https://zenodo.org/record/1594255.

- ↑ Emil Nylander: Über alkalische Wismuthlösung als Reagens auf Traubenzucker im Harne, Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie. Volume 8, Issue 3, 1884, p. 175–185 Abstract. (in German).

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 124.2 124.3 124.4 124.5 124.6 124.7 124.8 Georg Schwedt: Zuckersüße Chemie. John Wiley & Sons, 2012, ISBN:978-3-527-66001-8, p. 102 (in German).

- ↑ Trinder, P. (1969). "Determination of Glucose in Blood Using Glucose Oxidase with an Alternative Oxygen Acceptor". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 6: 24–27. doi:10.1177/000456326900600108.

- ↑ Mizoguchi, Makoto; Ishiyama, Munetaka; Shiga, Masanobu (1998). "Water-soluble chromogenic reagent for colorimetric detection of hydrogen peroxide—an alternative to 4-aminoantipyrine working at a long wavelength". Analytical Communications 35 (2): 71–74. doi:10.1039/A709038B.

- ↑ Wang, J. (2008). "Electrochemical glucose biosensors". Chemical Reviews 108 (2): 814–825. doi:10.1021/cr068123a. PMID 18154363..

- ↑ Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Deng, C.; Xiao, C.; Yang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Yao, S. (2008). "Amperometric glucose biosensor based on boron-doped carbon nanotubes modified electrode". Talanta 76 (4): 763–767. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2008.04.023. PMID 18656655.

- ↑ Wang, Guangfeng; Wei, Yan; Zhang, Wei; Zhang, Xiaojun; Fang, Bin; Wang, Lun (2010). "Enzyme-free amperometric sensing of glucose using Cu-CuO nanowire composites". Microchimica Acta 168 (1–2): 87–92. doi:10.1007/s00604-009-0260-1.

- ↑ Ohara, T. J.; Rajagopalan, R.; Heller, A. (1994). ""Wired" enzyme electrodes for amperometric determination of glucose or lactate in the presence of interfering substances". Analytical Chemistry 66 (15): 2451–2457. doi:10.1021/ac00087a008. PMID 8092486.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Borisov, S. M.; Wolfbeis, O. S. (2008). "Optical biosensors". Chemical Reviews 108 (2): 423–461. doi:10.1021/cr068105t. PMID 18229952.

- ↑ Ferri, S.; Kojima, K.; Sode, K. (2011). "Review of glucose oxidases and glucose dehydrogenases: A bird's eye view of glucose sensing enzymes". Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 5 (5): 1068–76. doi:10.1177/193229681100500507. PMID 22027299.

- ↑ Mader, Heike S.; Wolfbeis, Otto S. (2008). "Boronic acid based probes for microdetermination of saccharides and glycosylated biomolecules". Microchimica Acta 162 (1–2): 1–34. doi:10.1007/s00604-008-0947-8.

- ↑ Wolfbeis, Otto S.; Oehme, Ines; Papkovskaya, Natalya; Klimant, Ingo (2000). "Sol–gel based glucose biosensors employing optical oxygen transducers, and a method for compensating for variable oxygen background". Biosensors and Bioelectronics 15 (1–2): 69–76. doi:10.1016/S0956-5663(99)00073-1. PMID 10826645.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 Galant, A. L.; Kaufman, R. C.; Wilson, J. D. (2015). "Glucose: Detection and analysis". Food Chemistry 188: 149–160. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.071. PMID 26041177.

- ↑ Sanz, M. L.; Sanz, J.; Martínez-Castro, I. (2004). "Gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for the qualitative and quantitative determination of disaccharides and trisaccharides in honey.". Journal of Chromatography A 1059 (1–2): 143–148. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2004.09.095. PMID 15628134.

- ↑ Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology in Golm Database (2007-07-19). "Glucose mass spectrum". http://gmd.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/Spectrums/8dee81a1-8d98-4a73-b55d-9de42f10e190.aspx.

- ↑ Cabañero, A. I.; Recio, J. L.; Rupérez, M. (2006). "Liquid chromatography coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometry: a new perspective on honey adulteration detection.". J Agric Food Chem 54 (26): 9719–9727. doi:10.1021/jf062067x. PMID 17177492.

- ↑ Becker, M.; Liebner, F.; Rosenau, T.; Potthast, A. (2013). "Ethoximation-silylation approach for mono- and disaccharide analysis and characterization of their identification parameters by GC/MS". Talanta 115: 642–51. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.05.052. PMID 24054643.

- ↑ Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker: wayback=20100331071121 Anlagen zum Positionspapier der Fachgruppe Nuklearchemie , February 2000.

- ↑ Maschauer, S.; Prante, O. (2014). "Sweetening pharmaceutical radiochemistry by (18)f-fluoroglycosylation: A short review". BioMed Research International 2014: 1–16. doi:10.1155/2014/214748. PMID 24991541.

|