Chemistry:Ideal chain

In polymer chemistry, an ideal chain (or freely-jointed chain) is the simplest model to describe polymers, such as nucleic acids and proteins. It assumes that the monomers in a polymer are located at the steps of a hypothetical random walker that does not remember its previous steps. By neglecting interactions among monomers, this model assumes that two (or more) monomers can occupy the same location. Although it is simple, its generality gives insight about the physics of polymers.

In this model, monomers are rigid rods of a fixed length l, and their orientation is completely independent of the orientations and positions of neighbouring monomers. In some cases, the monomer has a physical interpretation, such as an amino acid in a polypeptide. In other cases, a monomer is simply a segment of the polymer that can be modeled as behaving as a discrete, freely jointed unit. If so, l is the Kuhn length. For example, chromatin is modeled as a polymer in which each monomer is a segment approximately 14-46 kbp in length.[1]

The model

N mers form the polymer, whose total unfolded length is: [math]\displaystyle{ L = N \, l, }[/math] where N is the number of mers.

In this very simple approach where no interactions between mers are considered, the energy of the polymer is taken to be independent of its shape, which means that at thermodynamic equilibrium, all of its shape configurations are equally likely to occur as the polymer fluctuates in time, according to the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

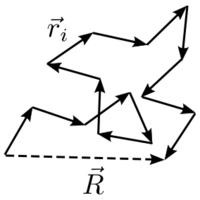

Let us call [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] the total end to end vector of an ideal chain and [math]\displaystyle{ \vec r_1,\ldots ,\vec r_N }[/math] the vectors corresponding to individual mers. Those random vectors have components in the three directions of space. Most of the expressions given in this article assume that the number of mers N is large, so that the central limit theorem applies. The figure below shows a sketch of a (short) ideal chain.

The two ends of the chain are not coincident, but they fluctuate around each other, so that of course: [math]\displaystyle{ \left\langle \vec{R} \right\rangle = \sum_{i=1}^N \left\langle \vec r_i \right\rangle = \vec 0~ }[/math]

Throughout the article the [math]\displaystyle{ \langle \rangle }[/math] brackets will be used to denote the mean (of values taken over time) of a random variable or a random vector, as above.

Since [math]\displaystyle{ \vec r_1,\ldots ,\vec r_N }[/math] are independent, it follows from the Central limit theorem that [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] is distributed according to a normal distribution (or gaussian distribution): precisely, in 3D, [math]\displaystyle{ R_x, R_y, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R_z }[/math] are distributed according to a normal distribution of mean 0 and of variance: [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma ^2 = \langle R_x^2 \rangle - \langle R_x \rangle ^2 =\langle R_x^2 \rangle -0 }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \left\langle R_x^2 \right\rangle = \left\langle R_y^2 \right\rangle = \left\langle R_z^2 \right\rangle = N \, \frac{l^2}{3} }[/math]

So that [math]\displaystyle{ \langle {R^2} \rangle = N\, l^2 = L \, l~ }[/math]. The end to end vector of the chain is distributed according to the following probability density function: [math]\displaystyle{ P(\vec R) = \left ( \frac{3}{2 \pi N l^2} \right )^{3/2}e^{-\frac{3 \left|\vec R\right|^2}{2 N l^2}} }[/math]

The average end-to-end distance of the polymer is: [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{\left\langle {R^2} \right\rangle} = \sqrt N \, l = \sqrt{L \, l}~ }[/math]

A quantity frequently used in polymer physics is the radius of gyration: [math]\displaystyle{ \langle\mathit{R}_G\rangle = \frac{ \sqrt N\, l }{ \sqrt 6\ } }[/math]

It is worth noting that the above average end-to-end distance, which in the case of this simple model is also the typical amplitude of the system's fluctuations, becomes negligible compared to the total unfolded length of the polymer [math]\displaystyle{ N\,l }[/math] at the thermodynamic limit. This result is a general property of statistical systems.

Mathematical remark: the rigorous demonstration of the expression of the density of probability [math]\displaystyle{ P(\vec R) }[/math] is not as direct as it appears above: from the application of the usual (1D) central limit theorem one can deduce that [math]\displaystyle{ R_x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R_y }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R_z }[/math] are distributed according to a centered normal distribution of variance [math]\displaystyle{ N\, l^2/3 }[/math]. Then, the expression given above for [math]\displaystyle{ P(\vec R) }[/math] is not the only one that is compatible with such distribution for [math]\displaystyle{ R_x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R_y }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R_z }[/math]. However, since the components of the vectors [math]\displaystyle{ \vec r_1,\ldots ,\vec r_N }[/math] are uncorrelated for the random walk we are considering, it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ R_x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R_y }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R_z }[/math] are also uncorrelated. This additional condition can only be fulfilled if [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] is distributed according to [math]\displaystyle{ P(\vec R) }[/math]. Alternatively, this result can also be demonstrated by applying a multidimensional generalization of the central limit theorem, or through symmetry arguments.

Generality of the model

While the elementary model described above is totally unadapted to the description of real-world polymers at the microscopic scale, it does show some relevance at the macroscopic scale in the case of a polymer in solution whose monomers form an ideal mix with the solvent (in which case, the interactions between monomer and monomer, solvent molecule and solvent molecule, and between monomer and solvent are identical, and the system's energy can be considered constant, validating the hypotheses of the model).

The relevancy of the model is, however, limited, even at the macroscopic scale, by the fact that it does not consider any excluded volume for monomers (or, to speak in chemical terms, that it neglects steric effects). Since the N mers are of a rigid, fixed length, the model also does not consider bond stretching, though it can be extended to do so.[2]

Other fluctuating polymer models that consider no interaction between monomers and no excluded volume, like the worm-like chain model, are all asymptotically convergent toward this model at the thermodynamic limit. For purpose of this analogy a Kuhn segment is introduced, corresponding to the equivalent monomer length to be considered in the analogous ideal chain. The number of Kuhn segments to be considered in the analogous ideal chain is equal to the total unfolded length of the polymer divided by the length of a Kuhn segment.

Entropic elasticity of an ideal chain

If the two free ends of an ideal chain are pulled apart by some sort of device, then the device experiences a force exerted by the polymer. As the ideal chain is stretched, its energy remains constant, and its time-average, or internal energy, also remains constant, which means that this force necessarily stems from a purely entropic effect.

This entropic force is very similar to the pressure experienced by the walls of a box containing an ideal gas. The internal energy of an ideal gas depends only on its temperature, and not on the volume of its containing box, so it is not an energy effect that tends to increase the volume of the box like gas pressure does. This implies that the pressure of an ideal gas has a purely entropic origin.

What is the microscopic origin of such an entropic force or pressure? The most general answer is that the effect of thermal fluctuations tends to bring a thermodynamic system toward a macroscopic state that corresponds to a maximum in the number of microscopic states (or micro-states) that are compatible with this macroscopic state. In other words, thermal fluctuations tend to bring a system toward its macroscopic state of maximum entropy.

What does this mean in the case of the ideal chain? First, for our ideal chain, a microscopic state is characterized by the superposition of the states [math]\displaystyle{ \vec r_i }[/math] of each individual monomer (with i varying from 1 to N). In its solvent, the ideal chain is constantly subject to shocks from moving solvent molecules, and each of these shocks sends the system from its current microscopic state to another, very similar microscopic state. For an ideal polymer, as will be shown below, there are more microscopic states compatible with a short end-to-end distance than there are microscopic states compatible with a large end-to-end distance. Thus, for an ideal chain, maximizing its entropy means reducing the distance between its two free ends. Consequently, a force that tends to collapse the chain is exerted by the ideal chain between its two free ends.

In this section, the mean of this force will be derived. The generality of the expression obtained at the thermodynamic limit will then be discussed.

Ideal chain under length constraint

The case of an ideal chain whose two ends are attached to fixed points will be considered in this sub-section. The vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] joining these two points characterizes the macroscopic state (or macro-state) of the ideal chain. Each macro-state corresponds a certain number of micro-states, that we will call [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(\vec R) }[/math] (micro-states are defined in the introduction to this section). Since the ideal chain's energy is constant, each of these micro-states is equally likely to occur. The entropy associated to a macro-state is thus equal to: [math]\displaystyle{ S(\vec R) = k_\text{B} \log (\Omega(\vec R)), }[/math]where [math]\displaystyle{ k_\text{B} }[/math] is Boltzmann's constant

The above expression gives the absolute (quantum) entropy of the system. A precise determination of [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(\vec R) }[/math] would require a quantum model for the ideal chain, which is beyond the scope of this article. However, we have already calculated the probability density [math]\displaystyle{ P(\vec R) }[/math] associated with the end-to-end vector of the unconstrained ideal chain, above. Since all micro-states of the ideal chain are equally likely to occur, [math]\displaystyle{ P(\vec R) }[/math] is proportional to [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(\vec R) }[/math]. This leads to the following expression for the classical (relative) entropy of the ideal chain: [math]\displaystyle{ S(\vec R) = k_\text{B} \log (P(\vec R)) + C_{st}, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ C_{st} }[/math] is a fixed constant. Let us call [math]\displaystyle{ \vec F }[/math] the force exerted by the chain on the point to which its end is attached. From the above expression of the entropy, we can deduce an expression of this force. Suppose that, instead of being fixed, the positions of the two ends of the ideal chain are now controlled by an operator. The operator controls the evolution of the end to end vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math]. If the operator changes [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] by a tiny amount [math]\displaystyle{ d\vec{R} }[/math], then the variation of internal energy of the chain is zero, since the energy of the chain is constant. This condition can be written as: [math]\displaystyle{ 0 = dU = \delta W + \delta Q~ }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \delta W }[/math] is defined as the elementary amount of mechanical work transferred by the operator to the ideal chain, and [math]\displaystyle{ \delta Q }[/math] is defined as the elementary amount of heat transferred by the solvent to the ideal chain. Now, if we assume that the transformation imposed by the operator on the system is quasistatic (i.e., infinitely slow), then the system's transformation will be time-reversible, and we can assume that during its passage from macro-state [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] to macro-state [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R + d\vec{R} }[/math], the system passes through a series of thermodynamic equilibrium macro-states. This has two consequences:

- first, the amount of heat received by the system during the transformation can be tied to the variation of its entropy: [math]\displaystyle{ \delta Q = T \, dS~, }[/math] where T is the temperature of the chain.

- second, in order for the transformation to remain infinitely slow, the mean force exerted by the operator on the end points of the chain must balance the mean force exerted by the chain on its end points. Calling [math]\displaystyle{ \vec f_\text{op} }[/math] the force exerted by the operator and [math]\displaystyle{ \vec f }[/math] the force exerted by the chain, we have: [math]\displaystyle{ \delta W = \left\langle \vec f_\text{op} \right\rangle \cdot d\vec{R} = - \left\langle \vec f \right\rangle \cdot d\vec {R}~ }[/math]

We are thus led to: [math]\displaystyle{ \left\langle \vec f \right\rangle = T \frac{dS}{d\vec {R}} = \frac{k_\text{B} T}{P( \vec R)}\frac{dP( \vec R)}{d\vec {R}}~ }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \langle \vec f \rangle = - k_\text{B} T \frac{3 \vec R}{N l^2}~ }[/math]

The above equation is the equation of state of the ideal chain. Since the expression depends on the central limit theorem, it is only exact in the limit of polymers containing a large number of monomers (that is, the thermodynamic limit). It is also only valid for small end-to-end distances, relative to the overall polymer contour length, where the behavior is like a hookean spring. Behavior over larger force ranges can be modeled using a canonical ensemble treatment identical to magnetization of paramagnetic spins. For the arbitrary forces the extension-force dependence will be given by Langevin function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L} }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{R}{Nl} = \coth\left(\frac{fl}{k_\text{B}T}\right) - \frac{k_\text{B}T}{fl} = \mathcal{L}\left(\frac{fl}{k_\text{B}T}\right), }[/math] where the extension is [math]\displaystyle{ R=|\vec{R}| }[/math].

For the arbitrary extensions the force-extension dependence can be approximated by:[3] [math]\displaystyle{ \frac {fl}{k_\text{B}T} = \mathcal{L}^{-1}{\left(\frac {R}{Nl} \right)} \approx 3\frac {R}{Nl} + \frac{1}{5} \left(\frac {R}{Nl}\right)^{2}\sin \left(\frac{7R}{2Nl}\right) + \frac{\left(\frac {R}{Nl}\right)^{3}}{1-\frac {R}{Nl}}, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}^{-1} }[/math] is the inverse Langevin function, N is the number of bonds[4] in the molecule (therefore if the molecule has N bonds it has N+1 monomers making up the molecule.).

Finally, the model can be extended to even larger force ranges by inclusion of a stretch modulus along the polymer contour length. That is, by allowing the length of each unit of the chain to respond elastically to the applied force.[5]

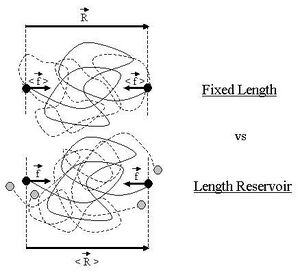

Ideal polymer exchanging length with a reservoir

Throughout this sub-section, as in the previous one, the two ends of the polymer are attached to a micro-manipulation device. This time, however, the device does not maintain the two ends of the ideal chain in a fixed position, but rather it maintains a constant pulling force [math]\displaystyle{ \vec f_\text{op} }[/math] on the ideal chain. In this case the two ends of the polymer fluctuate around a mean position [math]\displaystyle{ \langle \vec R \rangle }[/math]. The ideal chain reacts with a constant opposite force [math]\displaystyle{ \vec f = -\vec f_\text{op} }[/math].

For an ideal chain exchanging length with a reservoir, a macro-state of the system is characterized by the vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec f }[/math].

The change between an ideal chain of fixed length and an ideal chain in contact with a length reservoir is very much akin to the change between the micro-canonical ensemble and the canonical ensemble (see the Statistical mechanics article about this).[6] The change is from a state where a fixed value is imposed on a certain parameter, to a state where the system is left free to exchange this parameter with the outside. The parameter in question is energy for the microcanonical and canonical descriptions, whereas in the case of the ideal chain the parameter is the length of the ideal chain.

As in the micro-canonical and canonical ensembles, the two descriptions of the ideal chain differ only in the way they treat the system's fluctuations. They are thus equivalent at the thermodynamic limit. The equation of state of the ideal chain remains the same, except that [math]\displaystyle{ \vec R }[/math] is now subject to fluctuations: [math]\displaystyle{ \vec f = - k_\text{B} T \frac{3 \langle \vec R \rangle}{N l^2}~. }[/math]

Ideal chain under a constant force constraint - calculation

Consider a freely jointed chain of N bonds of length [math]\displaystyle{ l }[/math] subject to a constant elongational force f applied to its ends along the z axis and an environment temperature [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]. An example could be a chain with two opposite charges +q and -q at its ends in a constant electric field [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} }[/math] applied along the [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] axis as sketched in the figure on the right. If the direct Coulomb interaction between the charges is ignored, then there is a constant force [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{f} }[/math] at the two ends.

Different chain conformations are not equally likely, because they correspond to different energy of the chain in the external electric field. [math]\displaystyle{ U = -q\vec{E}\cdot \vec{R}= - \vec{f}\cdot \vec{R} = -f R_z }[/math]

Thus, different chain conformation have different statistical Boltzmann factors [math]\displaystyle{ \exp(-U/k_BT) }[/math].[4]

The partition function is: [math]\displaystyle{ Z = \sum_{\text{states}}\exp(-U/k_\text{B}T) = \sum_{\text{states}}\exp \left(\frac{f R_z}{k_\text{B} T}\right) }[/math]

Every monomer connection in the chain is characterize by a vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r}_i }[/math] of length [math]\displaystyle{ l }[/math] and angles [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_i, \varphi_i }[/math] in the spherical coordinate system. The end-to-end vector can be represented as: [math]\displaystyle{ R_z = \sum_{i=1}^N l \cos\theta_i }[/math]. Therefore:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} Z &=\int \exp\left(\frac{fl}{k_\text{B}T}\sum_{i=1}^N \cos\theta_i\right)\prod_{i=1}^N\sin\theta_i \, d\theta_i \, d\varphi_i \\ &=\left[\int_{0}^{\pi} 2\pi \text{ } \sin\theta_i \text{ } \exp \left(\frac{fl}{k_\text{B}T}\cos\theta_i \right) \, d\theta_i\right]^N\\ &=\left[\frac{2\pi}{fl/(k_\text{B} T)} \left(\exp \left({fl \over k_\text{B} T} \right) - \exp \left(-\frac{fl}{k_\text{B} T} \right) \right) \right]^N\\ &=\left[{4\pi \sinh(fl/(k_\text{B} T)) \over fl/(k_\text{B} T)}\right]^N \end{align} }[/math]

The Gibbs free energy G can be directly calculated from the partition function:

[math]\displaystyle{ G(T,f,N) = - k_\text{B} T \, \ln Z(T,f,N)=-N k_B T \left[\ln\left(4\pi \sinh\left(\frac{fl}{k_\text{B} T}\right)\right)-\ln\left(\frac{fl}{k_B T}\right)\right] }[/math]

The Gibbs free energy is used here because the ensemble of chains corresponds to constant temperature [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] and constant force [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] (analogous to the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, which has constant temperature and pressure).

The average end-to-end distance corresponding to a given force can be obtained as the derivative of the free energy:

[math]\displaystyle{ \langle R \rangle = - \frac{\partial G}{\partial f} = N l\left[\coth\left(\frac{fl}{k_\text{B} T}\right) - \frac{k_\text{B} T}{fl}\right] }[/math]

This expression is the Langevin function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L} }[/math], also mentioned in previous paragraphs:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}(\alpha) = \coth(\alpha)-{1 \over \alpha} }[/math] where, [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha = \frac{fl}{k_\text{B} T} }[/math].

For small relative elongations ([math]\displaystyle{ \left \langle R \right \rangle \ll R_\text{max} = lN }[/math]) the dependence is approximately linear, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}(\alpha)\cong \frac{\alpha}{3} \qquad \text{ for } \alpha \ll 1 }[/math] and follows Hooke's law as shown in previous paragraphs: [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{f} = k_\text{B} T \frac{3\left \langle \vec{R} \right \rangle}{Nl^2} }[/math]

See also

- Polymer

- Worm-like chain, a more complex polymer model

- Kuhn length

- Coil-globule transition

References

- ↑ Rippe, Karsten (2001). "Making contacts on a nucleic acid polymer". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 26 (12): 733–740. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01978-8.

- ↑ Buche, M.R.; Silberstein, M.N.; Grutzik, S.J. (2022). "Freely jointed chains with extensible links". Phys. Rev. E 106: 024502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.106.024502.

- ↑ Petrosyan, R. (2016). "Improved approximations for some polymer extension models". Rehol Acta 56: 21–26. doi:10.1007/s00397-016-0977-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Polymer Physics ISBN:019852059-X, 76, Rubinstein

- ↑ Smith, SB; Finzi, L; Bustamante, C (1992). "Direct mechanical measurements of the elasticity of single DNA molecules by using magnetic beads". Science 258 (5085): 1122–6. doi:10.1126/science.1439819. PMID 1439819. Bibcode: 1992Sci...258.1122S.

- ↑ Buche, M.R.; Silberstein, M.N. (2020). "Statistical mechanical constitutive theory of polymer networks: The inextricable links between distribution, behavior, and ensemble". Phys. Rev. E 102: 012501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.102.012501.

|