Chemistry:Okenane

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-(3,7,12,16,20,24-Hexamethylpentacosyl)-2,3,4-trimethylbenzene

| |

| Other names

chi,psi-Carotane

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C40H74 | |

| Molar mass | 555.032 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

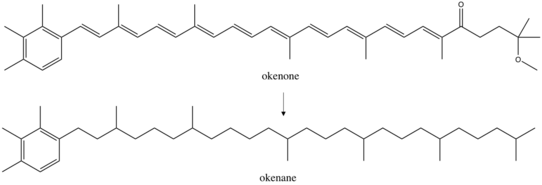

Okenane, the diagenetic end product of okenone, is a biomarker for Chromatiaceae, the purple sulfur bacteria.[1] These anoxygenic phototrophs use light for energy and sulfide as their electron donor and sulfur source. Discovery of okenane in marine sediments implies a past euxinic environment, where water columns were anoxic and sulfidic. This is potentially tremendously important for reconstructing past oceanic conditions, but so far okenane has only been identified in one Paleoproterozoic (1.6 billion years old) rock sample from Northern Australia.[2][3]

Background

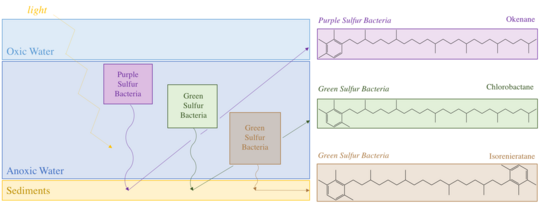

Okenone is a carotenoid,[4] a class of pigments ubiquitous across photosynthetic organisms. These conjugated molecules act as accessories in the light harvesting complex. Over 600 carotenoids are known, each with a variety of functional groups that alter their absorption spectrum. Okenone appears to be best adapted to the yellow-green transition (520 nm) of the visible spectrum, capturing light below marine plankton in the ocean. This depth varies based on the community structure of the water column. A survey of microbial blooms found Chromatiaceae anywhere between 1.5m and 24m depth, but more than 75% occurred above 12 meters.[5] Further planktonic sulfur bacteria occupy other niches: green sulfur bacteria, the Chlorobiaceae, that produce the carotenoid chlorobactene were found in greatest abundance above 6m while green sulfur bacteria that produce isorenieratene were predominantly identified above 17m. Finding any of these carotenoids in ancient rocks could constrain the depth of the oxic to anoxic transition as well as confine past ecology. Okenane and chlorobactane discovered in Australian Paleoproterozoic samples allowed conclusions of a temporarily shallow anoxic transition, likely between 12 and 25m.[2]

Okenone is synthesized in 12 species of Chromatiaceae, spanning eight genera. Other purple sulfur bacteria have acyclic carotenoid pigments like lycopene and rhodopin. However, geochemists largely study okenone because it is structurally unique. It is the only pigment with a 2,3,4 trimethylaryl substitution pattern. In contrast, the green sulfur bacteria produce 2,3,6 trimethylaryl isoprenoids.[6] The synthesis of these structures produce biological specificity that can distinguish the ecology of past environments. Okenone, chlorobactene, and isorenieratene are produced by sulfur bacteria through modification of lycopene. In okenone, the end group of lycopene produces a χ-ring, while chlorobactene has a φ-ring.[7] The first step in biosynthesis of these two pigments is similar, formation of a β-ring by a β-cyclase enzyme. Then the syntheses diverge, with carotene desaturase/methyltransferase enzyme transforming the β-ring end group into a χ-ring. Other reactions complete the synthesis to okenone: elongating the conjugation, adding a methoxy group, and inserting a ketone. However, only the first synthetic steps are well characterized biologically.

Preservation

Pigments and other biomarkers produced by organisms can evade microbial and chemical degradation and persist in sedimentary rocks.[8] Under conditions of preservation, the environment is often anoxic and reducing, leading to chemical loss of functional groups like double bonds and hydroxyl groups. The exact reactions during diagenesis are poorly understood, although some have proposed reductive desulphurization as a mechanism for saturation of okenone to okenane.[9][10] There is always the possibility that okenane is created by abiotic reactions, possibly from methyl shifts in β-carotene.[11] If this reaction was occurring, okenane would have multiple precursors and the biological specificity of the biomarker would be diminished. However, it is unlikely that isomer specific rearrangements of two methyl groups are occurring without enzymatic activity. The majority of studies conclude that okenane is a true biomarker of purple sulfur bacteria. However, other biological arguments against this interpretation hold merit.[12] Past organisms that synthesized okenone may not be modern analogues of purple sulfur bacteria. There may also be other okenone producing photosynthesizers in today's ocean that are uncharacterized. A further complication is horizontal gene transfer.[13] If Chromatiaceae gained the ability to create okenone more recently that the Paleoproterozoic, then the okenane does not track purple sulfur bacteria, but rather the original gene donor. These ambiguities indicate that interpretation of biomarkers in billion-year-old rocks will be limited by understanding of ancient metabolisms.

Measurement techniques

GC/MS

Prior to analysis, sedimentary rocks are extracted for organic matter. Typically, only less than one percent is extractable due to the thermal maturity of the source rock. The organic content is often separated into saturates, aromatics, and polars. Gas chromatography can be coupled to mass spectrometry to analyze the extracted aromatic fraction. Compounds elute from the column based on their mass-to-charge ratio (M/Z) and are displayed based on relative intensity. Peaks are assigned to compounds based on library searches, standards, and relative retention times. Some molecules have characteristic peaks that allow easy searches at particular mass-to-charge ratios. For the trimethylaryl isoprenoid okenane this characteristic peak occurs at M/Z of 134.

Isotope ratios

Carbon isotope ratios of purple and green sulfur bacteria are significantly different that other photosynthesizing organisms. The biomass of the purple sulfur bacteria, Chromatiaceae is often depleted in δ13C compared to typical oxygenic phototrophs while the green sulfur bacteria, Chlorobiaceae, are often enriched.[14] This offers an additional discrimination to determine ecological communities preserved in sedimentary rocks. For the biomarker okenane, the δ13C could be determined by an Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer.

Case study: Northern Australia

In modern environments, purple sulfur bacteria thrive in meromictic (permanently stratified) lakes[15] and silled fjords and are seen in few marine ecosystems. Hypersaline waters like the Black Sea are exceptions.[16] However, billions of years ago, when the oceans were anoxic and sulfidic, phototrophic sulfur bacteria had more habitable space. Researchers at the Australian National University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology investigated 1.6-billion-year-old rocks to examine the chemical conditions of the Paleoproterozoic ocean. Many believe that this time had deeply penetrating oxic water columns because of the disappearance of banded iron formations roughly 1.8 billion years ago. Others, spearheaded by Donald Canfield's 1998 Nature paper, believe that waters were euxinic. Examining rocks from the time uncovered biomarkers of both purple and green sulfur bacteria, adding evidence to support the Canfield Ocean hypothesis. The sedimentary outcrop analyzed was the Barney Creek Formation from the McArthur group in northern Australia. Sample analysis identified both the 2,3,6 trimethylarl isoprenoids (chlorobactane) of Chlorobiaceae and the 2,3,4 trimethylaryl isoprenoids (okenane) of Chromatiaceae. Both chlorobactane and okenane indicate a euxinic ocean, with sulfidic and anoxic surface conditions below 12-25m. The authors concluded that although oxygen was in the atmosphere, the Paleoproterozoic oceans were not completely oxygenated.[2]

See also

- Anoxic event

- Anoxygenic photosynthesis

- Biomarkers

- Carotenoids

- Green sulfur bacteria

- Purple sulfur bacteria

References

- ↑ Imhoff, Johannes F. (1995-01-01). "Taxonomy and Physiology of Phototrophic Purple Bacteria and Green Sulfur Bacteria". in Blankenship, Robert E. (in en). Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 2. Springer Netherlands. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/0-306-47954-0_1. ISBN 9780792336815.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Brocks, Jochen J.; Schaeffer, Philippe (2008-03-01). "Okenane, a biomarker for purple sulfur bacteria (Chromatiaceae), and other new carotenoid derivatives from the 1640 Ma Barney Creek Formation". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72 (5): 1396–1414. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2007.12.006. Bibcode: 2008GeCoA..72.1396B.

- ↑ Brocks, Jochen J.; Love, Gordon D.; Summons, Roger E.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Logan, Graham A.; Bowden, Stephen A. (2005). "Biomarker evidence for green and purple sulphur bacteria in a stratified Palaeoproterozoic sea". Nature 437 (7060): 866–870. doi:10.1038/nature04068. PMID 16208367. Bibcode: 2005Natur.437..866B.

- ↑ Schaeffer, Philippe; Adam, Pierre; Wehrung, Patrick; Albrecht, Pierre (1997-12-01). "Novel aromatic carotenoid derivatives from sulfur photosynthetic bacteria in sediments". Tetrahedron Letters 38 (48): 8413–8416. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)10235-0.

- ↑ Gemerden, Hans Van; Mas, Jordi (1995-01-01). Blankenship, Robert E.. ed (in en). Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Springer Netherlands. pp. 49–85. doi:10.1007/0-306-47954-0_4. ISBN 9780792336815.

- ↑ Summons, R. E.; Powell, T. G. (1987-03-01). "Identification of aryl isoprenoids in source rocks and crude oils: Biological markers for the green sulphur bacteria". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 51 (3): 557–566. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(87)90069-X. Bibcode: 1987GeCoA..51..557S.

- ↑ Vogl, K.; Bryant, D. A. (2012-05-01). "Biosynthesis of the biomarker okenone: χ-ring formation" (in en). Geobiology 10 (3): 205–215. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2011.00297.x. ISSN 1472-4669. PMID 22070388. Bibcode: 2012Gbio...10..205V.

- ↑ Brocks, Jochen J.; Grice, Kliti (2011-01-01). Reitner, Joachim. ed (in en). Encyclopedia of Geobiology. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. Springer Netherlands. pp. 147–167. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9212-1_30. ISBN 9781402092114.

- ↑ Hebting, Y.; Schaeffer, P.; Behrens, A.; Adam, P.; Schmitt, G.; Schneckenburger, P.; Bernasconi, S. M.; Albrecht, P. (2006-06-16). "Biomarker Evidence for a Major Preservation Pathway of Sedimentary Organic Carbon" (in en). Science 312 (5780): 1627–1631. doi:10.1126/science.1126372. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16690819. Bibcode: 2006Sci...312.1627H.

- ↑ Werne, Josef P.; Lyons, Timothy W.; Hollander, David J.; Schouten, Stefan; Hopmans, Ellen C.; Sinninghe Damsté, Jaap S. (2008-07-15). "Investigating pathways of diagenetic organic matter sulfurization using compound-specific sulfur isotope analysis". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 72 (14): 3489–3502. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2008.04.033. Bibcode: 2008GeCoA..72.3489W.

- ↑ Koopmans, Martin P.; Schouten, Stefan; Kohnen, Math E. L.; Sinninghe Damsté, Jaap S. (1996-12-01). "Restricted utility of aryl isoprenoids as indicators for photic zone anoxia". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 60 (23): 4873–4876. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00303-1. Bibcode: 1996GeCoA..60.4873K.

- ↑ Brocks, Jochen J.; Banfield, Jillian (2009). "Unravelling ancient microbial history with community proteogenomics and lipid geochemistry". Nature Reviews Microbiology 7 (8): 601–609. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2167. PMID 19609261.

- ↑ Cobbs, Cassidy; Heath, Jeremy; Stireman III, John O.; Abbot, Patrick (2013-08-01). "Carotenoids in unexpected places: Gall midges, lateral gene transfer, and carotenoid biosynthesis in animals". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68 (2): 221–228. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.012. PMID 23542649.

- ↑ Zyakun, A. M.; Lunina, O. N.; Prusakova, T. S.; Pimenov, N. V.; Ivanov, M. V. (2009-12-06). "Fractionation of stable carbon isotopes by photoautotrophically growing anoxygenic purple and green sulfur bacteria" (in en). Microbiology 78 (6): 757. doi:10.1134/S0026261709060137. ISSN 0026-2617.

- ↑ Overmann, Jörg; Beatty, J. Thomas; Hall, Ken J.; Pfennig, Norbert; Northcote, Tom G. (1991-07-01). "Characterization of a dense, purple sulfur bacterial layer in a meromictic salt lake" (in en). Limnology and Oceanography 36 (5): 846–859. doi:10.4319/lo.1991.36.5.0846. ISSN 1939-5590. Bibcode: 1991LimOc..36..846O. https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/3260/1/003.pdf.

- ↑ Hashwa, F. A.; Trüper, H. G. (1978). "Viable phototrophic sulfur bacteria from the Black-Sea bottom" (in en). Helgoländer Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen 31 (1–2): 249–253. doi:10.1007/BF02297000. ISSN 0017-9957. Bibcode: 1978HWM....31..249H.

|