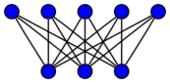

Complete bipartite graph

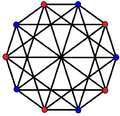

| Complete bipartite graph | |

|---|---|

A complete bipartite graph with m = 5 and n = 3 | |

| Vertices | n + m |

| Edges | mn |

| Radius | |

| Diameter | |

| Girth | |

| Automorphisms | |

| Chromatic number | 2 |

| Chromatic index | max{m, n} |

| Spectrum | |

| Notation | K{m,n} |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a complete bipartite graph or biclique is a special kind of bipartite graph where every vertex of the first set is connected to every vertex of the second set.[1][2]

Graph theory itself is typically dated as beginning with Leonhard Euler's 1736 work on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg. However, drawings of complete bipartite graphs were already printed as early as 1669, in connection with an edition of the works of Ramon Llull edited by Athanasius Kircher.[3][4] Llull himself had made similar drawings of complete graphs three centuries earlier.[3]

Definition

A complete bipartite graph is a graph whose vertices can be partitioned into two subsets V1 and V2 such that no edge has both endpoints in the same subset, and every possible edge that could connect vertices in different subsets is part of the graph. That is, it is a bipartite graph (V1, V2, E) such that for every two vertices v1 ∈ V1 and v2 ∈ V2, v1v2 is an edge in E. A complete bipartite graph with partitions of size |V1| = m and |V2| = n, is denoted Km,n;[1][2] every two graphs with the same notation are isomorphic.

Examples

- For any k, K1,k is called a star.[2] All complete bipartite graphs which are trees are stars.

- The graph K1,3 is called a claw, and is used to define the claw-free graphs.[5]

- The graph K3,3 is called the utility graph. This usage comes from a standard mathematical puzzle in which three utilities must each be connected to three buildings; it is impossible to solve without crossings due to the nonplanarity of K3,3.[6]

- The maximal bicliques found as subgraphs of the digraph of a relation are called concepts. When a lattice is formed by taking meets and joins of these subgraphs, the relation has an Induced concept lattice. This type of analysis of relations is called formal concept analysis.

Properties

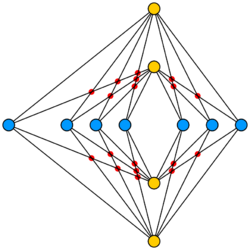

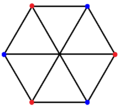

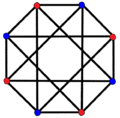

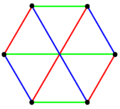

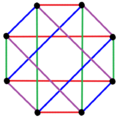

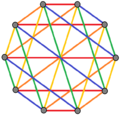

| K3,3 | K4,4 | K5,5 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

3 edge-colorings |

4 edge-colorings |

5 edge-colorings |

| Regular complex polygons of the form 2{4}p have complete bipartite graphs with 2p vertices (red and blue) and p2 2-edges. They also can also be drawn as p edge-colorings. | ||

- Given a bipartite graph, testing whether it contains a complete bipartite subgraph Ki,i for a parameter i is an NP-complete problem.[8]

- A planar graph cannot contain K3,3 as a minor; an outerplanar graph cannot contain K3,2 as a minor (These are not sufficient conditions for planarity and outerplanarity, but necessary). Conversely, every nonplanar graph contains either K3,3 or the complete graph K5 as a minor; this is Wagner's theorem.[9]

- Every complete bipartite graph. Kn,n is a Moore graph and a (n,4)-cage.[10]

- The complete bipartite graphs Kn,n and Kn,n+1 have the maximum possible number of edges among all triangle-free graphs with the same number of vertices; this is Mantel's theorem. Mantel's result was generalized to k-partite graphs and graphs that avoid larger cliques as subgraphs in Turán's theorem, and these two complete bipartite graphs are examples of Turán graphs, the extremal graphs for this more general problem.[11]

- The complete bipartite graph Km,n has a vertex covering number of min{m, n} and an edge covering number of max{m, n}.

- The complete bipartite graph Km,n has a maximum independent set of size max{m, n}.

- The adjacency matrix of a complete bipartite graph Km,n has eigenvalues √nm, −√nm and 0; with multiplicity 1, 1 and n + m − 2 respectively.[12]

- The Laplacian matrix of a complete bipartite graph Km,n has eigenvalues n + m, n, m, and 0; with multiplicity 1, m − 1, n − 1 and 1 respectively.

- A complete bipartite graph Km,n has mn−1 nm−1 spanning trees.[13]

- A complete bipartite graph Km,n has a maximum matching of size min{m,n}.

- A complete bipartite graph Kn,n has a proper n-edge-coloring corresponding to a Latin square.[14]

- Every complete bipartite graph is a modular graph: every triple of vertices has a median that belongs to shortest paths between each pair of vertices.[15]

See also

- Biclique-free graph, a class of sparse graphs defined by avoidance of complete bipartite subgraphs

- Crown graph, a graph formed by removing a perfect matching from a complete bipartite graph

- Complete multipartite graph, a generalization of complete bipartite graphs to more than two sets of vertices

- Biclique attack

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bondy, John Adrian; Murty, U. S. R. (1976), Graph Theory with Applications, North-Holland, p. 5, ISBN 0-444-19451-7, https://archive.org/details/graphtheorywitha0000bond/page/5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Diestel, Reinhard (2005), Graph Theory (3rd ed.), Springer, ISBN 3-540-26182-6. Electronic edition, page 17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Knuth, Donald E. (2013), "Two thousand years of combinatorics", in Wilson, Robin; Watkins, John J., Combinatorics: Ancient and Modern, Oxford University Press, pp. 7–37, ISBN 0191630624, https://books.google.com/books?id=vj1oAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA7.

- ↑ Read, Ronald C.; Wilson, Robin J. (1998), An Atlas of Graphs, Clarendon Press, p. ii, ISBN 9780198532897.

- ↑ Lovász, László; Plummer, Michael D. (2009), Matching theory, Providence, RI: AMS Chelsea, p. 109, ISBN 978-0-8218-4759-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=yW3WSVq8ygcC&pg=PA109. Corrected reprint of the 1986 original.

- ↑ Gries, David; Schneider, Fred B. (1993), A Logical Approach to Discrete Math, Springer, p. 437, ISBN 9780387941158, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZWTDQ6H6gsUC&pg=PA437.

- ↑ Coxeter, Regular Complex Polytopes, second edition, p.114

- ↑ Garey, Michael R.; Johnson, David S. (1979), "[GT24] Balanced complete bipartite subgraph", Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness, W. H. Freeman, p. 196, ISBN 0-7167-1045-5.

- ↑ Diestel 2005, p. 105

- ↑ Biggs, Norman (1993), Algebraic Graph Theory, Cambridge University Press, p. 181, ISBN 9780521458979, https://books.google.com/books?id=6TasRmIFOxQC&pg=PA181.

- ↑ Bollobás, Béla (1998), Modern Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 184, Springer, p. 104, ISBN 9780387984889, https://books.google.com/books?id=SbZKSZ-1qrwC&pg=PA104.

- ↑ (Bollobás 1998), p. 266.

- ↑ Jungnickel, Dieter (2012), Graphs, Networks and Algorithms, Algorithms and Computation in Mathematic, 5, Springer, p. 557, ISBN 9783642322785, https://books.google.com/books?id=PrXxFHmchwcC&pg=PA557.

- ↑ Jensen, Tommy R.; Toft, Bjarne (2011), Graph Coloring Problems, Wiley Series in Discrete Mathematics and Optimization, 39, Wiley, p. 16, ISBN 9781118030745, https://books.google.com/books?id=leL0Y5N0bFoC&pg=PA16.

- ↑ Bandelt, H.-J.; Dählmann, A.; Schütte, H. (1987), "Absolute retracts of bipartite graphs", Discrete Applied Mathematics 16 (3): 191–215, doi:10.1016/0166-218X(87)90058-8.

|