Latin square

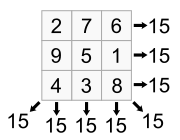

In combinatorics and in experimental design, a Latin square is an n × n array filled with n different symbols, each occurring exactly once in each row and exactly once in each column. An example of a 3×3 Latin square is

| A | B | C |

| C | A | B |

| B | C | A |

The name "Latin square" was inspired by mathematical papers by Leonhard Euler (1707–1783), who used Latin characters as symbols,[2][3] but any set of symbols can be used: in the above example, the alphabetic sequence A, B, C can be replaced by the integer sequence 1, 2, 3. Euler began the general theory of Latin squares.[4]

History

The Korean mathematician Choi Seok-jeong was the first to publish an example of Latin squares of order nine, in order to construct a magic square in 1700, predating Leonhard Euler by 67 years.[5]

Counting

This account follows (McKay Meynert).[6]

The counting of Latin squares has a long history, but the published accounts contain many errors. Euler in 1782,[7] and Cayley in 1890,[8] both knew the number of reduced Latin squares up to order five. In 1915, MacMahon[9] approached the problem in a different way, but initially obtained the wrong value for order five. M.Frolov in 1890,[10] and Tarry in 1901,[11][12] found the number of reduced squares of order six. M. Frolov gave an incorrect count of reduced squares of order seven. R.A. Fisher and F. Yates,[13] unaware of earlier work of E. Schönhardt,[14] gave the number of isotopy classes of orders up to six. In 1939, H. W. Norton found 562 isotopy classes of order seven,[15] but acknowledged that his method was incomplete. A. Sade, in 1951,[16] but privately published earlier in 1948, and P. N. Saxena[17] found more classes and, in 1966, D. A. Preece noted that this corrected Norton's result to 564 isotopy classes.[18] However, in 1968, J. W. Brown announced an incorrect value of 563,[19] which has often been repeated. He also gave the wrong number of isotopy classes of order eight. The correct number of reduced squares of order eight had already been found by M. B. Wells in 1967,[20] and the numbers of isotopy classes, in 1990, by G. Kolesova, C.W.H. Lam and L. Thiel.[21] The number of reduced squares for order nine was obtained by S. E. Bammel and J. Rothstein,[22] for order 10 by B. D. McKay and E. Rogoyski,[23] and for order 11 by B. D. McKay and I. M. Wanless.[24]

Reduced form

A Latin square is said to be reduced (also, normalized or in standard form) if both its first row and its first column are in their natural order.[25] For example, the Latin square above is not reduced because its first column is A, C, B rather than A, B, C.

Any Latin square can be reduced by permuting (that is, reordering) the rows and columns. Here switching the above matrix's second and third rows yields the following square:

| A | B | C |

| B | C | A |

| C | A | B |

This Latin square is reduced; both its first row and its first column are alphabetically ordered A, B, C.

Properties

Orthogonal array representation

If each entry of an n × n Latin square is written as a triple (r,c,s), where r is the row, c is the column, and s is the symbol, we obtain a set of n2 triples called the orthogonal array representation of the square. For example, the orthogonal array representation of the Latin square

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 |

is

- { (1, 1, 1), (1, 2, 2), (1, 3, 3), (2, 1, 2), (2, 2, 3), (2, 3, 1), (3, 1, 3), (3, 2, 1), (3, 3, 2) },

where for example the triple (2, 3, 1) means that in row 2 and column 3 there is the symbol 1. Orthogonal arrays are usually written in array form where the triples are the rows, such as

| r | c | s |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 |

The definition of a Latin square can be written in terms of orthogonal arrays:

- A Latin square is a set of n2 triples (r, c, s), where 1 ≤ r, c, s ≤ n, such that all ordered pairs (r, c) are distinct, all ordered pairs (r, s) are distinct, and all ordered pairs (c, s) are distinct.

This means that the n2 ordered pairs (r, c) are all the pairs (i, j) with 1 ≤ i, j ≤ n, once each. The same is true of the ordered pairs (r, s) and the ordered pairs (c, s).

The orthogonal array representation shows that rows, columns and symbols play rather similar roles, as will be made clear below.

Equivalence classes of Latin squares

Many operations on a Latin square produce another Latin square (for example, turning it upside down).

If we permute the rows, permute the columns, or permute the names of the symbols of a Latin square, we obtain a new Latin square said to be isotopic to the first. Isotopism is an equivalence relation, so the set of all Latin squares is divided into subsets, called isotopy classes, such that two squares in the same class are isotopic and two squares in different classes are not isotopic.

A stronger form of equivalence exists. Two Latin squares L1 and L2 of side n with common symbol set S that is also the index set for the rows and columns of each square are isomorphic if there is a bijection g: S → S such that g(L1(i, j)) = L2(g(i), g(j)) for all i, j in S.[26] An alternate way to define isomorphic Latin squares is to say that a pair of isotopic Latin squares are isomorphic if the three bijections used to show that they are isotopic are, in fact, equal.[27] Isomorphism is also an equivalence relation and its equivalence classes are called isomorphism classes.

Another type of operation is easiest to explain using the orthogonal array representation of the Latin square. If we systematically and consistently reorder the three items in each triple (that is, permute the three columns in the array form), another orthogonal array (and, thus, another Latin square) is obtained. For example, we can replace each triple (r,c,s) by (c,r,s) which corresponds to transposing the square (reflecting about its main diagonal), or we could replace each triple (r,c,s) by (c,s,r), which is a more complicated operation. Altogether there are 6 possibilities including "do nothing", giving us 6 Latin squares called the conjugates (also parastrophes) of the original square.[28]

Finally, we can combine these two equivalence operations: two Latin squares are said to be paratopic, also main class isotopic, if one of them is isotopic to a conjugate of the other. This is again an equivalence relation, with the equivalence classes called main classes, species, or paratopy classes.[28] Each main class contains up to six isotopy classes.

Number of n × n Latin squares

There is no known easily computable formula for the number Ln of n × n Latin squares with symbols 1, 2, ..., n. The most accurate upper and lower bounds known for large n are far apart. One classic result[29] is that

A simple and explicit formula for the number of Latin squares was published in 1992, but it is still not easily computable due to the exponential increase in the number of terms. This formula for the number Ln of n × n Latin squares is where Bn is the set of all n × n {0, 1}-matrices, σ0(A) is the number of zero entries in matrix A, and per(A) is the permanent of matrix A.[30]

The table below contains all known exact values. It can be seen that the numbers grow exceedingly quickly. For each n, the number of Latin squares altogether (sequence A002860 in the OEIS) is n! (n − 1)! times the number of reduced Latin squares (sequence A000315 in the OEIS).

| n | reduced Latin squares of size n (sequence A000315 in the OEIS) |

all Latin squares of size n (sequence A002860 in the OEIS) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 12 |

| 4 | 4 | 576 |

| 5 | 56 | 161,280 |

| 6 | 9,408 | 812,851,200 |

| 7 | 16,942,080 | 61,479,419,904,000 |

| 8 | 535,281,401,856 | 108,776,032,459,082,956,800 |

| 9 | 377,597,570,964,258,816 | 5,524,751,496,156,892,842,531,225,600 |

| 10 | 7,580,721,483,160,132,811,489,280 | 9,982,437,658,213,039,871,725,064,756,920,320,000 |

| 11 | 5,363,937,773,277,371,298,119,673,540,771,840 | 776,966,836,171,770,144,107,444,346,734,230,682,311,065,600,000 |

| 12 | 1.62 × 1044 | |

| 13 | 2.51 × 1056 | |

| 14 | 2.33 × 1070 | |

| 15 | 1.50 × 1086 |

For each n, each isotopy class (sequence A040082 in the OEIS) contains up to (n!)3 Latin squares (the exact number varies), while each main class (sequence A003090 in the OEIS) contains either 1, 2, 3 or 6 isotopy classes.

| n | main classes | isotopy classes | structurally distinct squares |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 192 |

| 6 | 12 | 22 | 145,164 |

| 7 | 147 | 564 | 1,524,901,344 |

| 8 | 283,657 | 1,676,267 | |

| 9 | 19,270,853,541 | 115,618,721,533 | |

| 10 | 34,817,397,894,749,939 | 208,904,371,354,363,006 | |

| 11 | 2,036,029,552,582,883,134,196,099 | 12,216,177,315,369,229,261,482,540 |

The number of structurally distinct Latin squares (i.e. the squares cannot be made identical by means of rotation, reflection, and permutation of the symbols) for n = 1 up to 7 is 1, 1, 1, 12, 192, 145164, 1524901344 respectively (sequence A264603 in the OEIS).

Examples

We give one example of a Latin square from each main class up to order five.

They present, respectively, the multiplication tables of the following groups:

- {0} – the trivial 1-element group

- – the binary group

- – cyclic group of order 3

- – the Klein four-group

- – cyclic group of order 4

- – cyclic group of order 5

- the last one is an example of a quasigroup, or rather a loop, which is not associative.

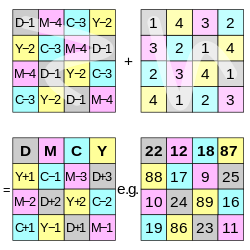

Orthogonal pairs

Two Latin squares of the same order n are called orthogonal if, by overlaying them, one gets every ordered pair (a,b) of symbols where a is a symbol in the first square and b is one in the second square. Orthogonal pairs and more generally sets of pairwise orthogonal Latin squares are important in design theory and finite geometry.

Transversals and rainbow matchings

A transversal in a Latin square is a choice of n cells, where each row contains one cell, each column contains one cell, and there is one cell containing each symbol.

One can consider a Latin square as a complete bipartite graph in which the rows are vertices of one part, the columns are vertices of the other part, each cell is an edge (between its row and its column), and the symbols are colors. The rules of the Latin squares imply that this is a proper edge coloring. With this definition, a Latin transversal is a matching in which each edge has a different color; such a matching is called a rainbow matching.

Therefore, many results on Latin squares/rectangles are contained in papers with the term "rainbow matching" in their title, and vice versa.[31]

Some Latin squares have no transversal. For example, when n is even, an n-by-n Latin square in which the value of cell i,j is (i+j) mod n has no transversal. Here are two examples:In 1967, H. J. Ryser conjectured that, when n is odd, every n-by-n Latin square has a transversal.[32]

In 1975, S. K. Stein and Brualdi conjectured that, when n is even, every n-by-n Latin square has a partial transversal of size n−1.[33]

A more general conjecture of Stein is that a transversal of size n−1 exists not only in Latin squares but also in any n-by-n array of n symbols, as long as each symbol appears exactly n times.[32]

Some weaker versions of these conjectures have been proved:

- Every n-by-n Latin square has a partial transversal of size 2n/3.[34]

- Every n-by-n Latin square has a partial transversal of size n − sqrt(n).[35]

- Every n-by-n Latin square has a partial transversal of size n − 11 log22(n).[36]

- Every n-by-n Latin square has a partial transversal of size n − O(log n/loglog n).[37]

- Every large enough n-by-n Latin square has a partial transversal of size n −1.[38] (Preprint)

Algorithms

For small squares it is possible to generate permutations and test whether the Latin square property is met. For larger squares, Jacobson and Matthews' algorithm allows sampling from a uniform distribution over the space of n × n Latin squares.[39]

Applications

Statistics and mathematics

- In the design of experiments, Latin squares are a special case of row-column designs for two blocking factors.[40][41]

- In algebra, Latin squares are related to generalizations of groups; in particular, Latin squares are characterized as being the multiplication tables (Cayley tables) of quasigroups. A binary operation whose table of values forms a Latin square is said to obey the Latin square property.

Error correcting codes

Sets of Latin squares that are orthogonal to each other have found an application as error correcting codes in situations where communication is disturbed by more types of noise than simple white noise, such as when attempting to transmit broadband Internet over powerlines.[42][43][44]

Firstly, the message is sent by using several frequencies, or channels, a common method that makes the signal less vulnerable to noise at any one specific frequency. A letter in the message to be sent is encoded by sending a series of signals at different frequencies at successive time intervals. In the example below, the letters A to L are encoded by sending signals at four different frequencies, in four time slots. The letter C, for instance, is encoded by first sending at frequency 3, then 4, 1 and 2.

The encoding of the twelve letters are formed from three Latin squares that are orthogonal to each other. Now imagine that there's added noise in channels 1 and 2 during the whole transmission. The letter A would then be picked up as

In other words, in the first slot we receive signals from both frequency 1 and frequency 2; while the third slot has signals from frequencies 1, 2 and 3. Because of the noise, we can no longer tell if the first two slots were 1,1 or 1,2 or 2,1 or 2,2. But the 1,2 case is the only one that yields a sequence matching a letter in the above table, the letter A. Similarly, we may imagine a burst of static over all frequencies in the third slot:

Again, we are able to infer from the table of encodings that it must have been the letter A being transmitted. The number of errors this code can spot is one less than the number of time slots. It has also been proven that if the number of frequencies is a prime or a power of a prime, the orthogonal Latin squares produce error detecting codes that are as efficient as possible.

Mathematical puzzles

The problem of determining if a partially filled square can be completed to form a Latin square is NP-complete.[45]

The popular Sudoku puzzles are a special case of Latin squares; any solution to a Sudoku puzzle is a Latin square. Sudoku imposes the additional restriction that nine particular 3×3 adjacent subsquares must also contain the digits 1–9 (in the standard version). See also Mathematics of Sudoku.

The more recent KenKen and Strimko puzzles are also examples of Latin squares.

Board games

Latin squares have been used as the basis for several board games, notably the popular abstract strategy game Kamisado.

Agronomic research

Latin squares are used in the design of agronomic research experiments to minimise experimental errors.[46]

Heraldry

The Latin square also figures in the arms of the Statistical Society of Canada,[47] being specifically mentioned in its blazon. Also, it appears in the logo of the International Biometric Society.[48]

Generalizations

- A Latin rectangle is a generalization of a Latin square in which there are n columns and n possible values, but the number of rows may be smaller than n. Each value still appears at most once in each row and column.

- A Graeco-Latin square is a pair of two Latin squares such that, when one is laid on top of the other, each ordered pair of symbols appears exactly once.

- A Latin hypercube is a generalization of a Latin square from two dimensions to multiple dimensions.

See also

- Block design

- Combinatorial design

- Eight queens puzzle

- Futoshiki

- Magic square

- Problems in Latin squares

- Rook's graph, a graph that has Latin squares as its colorings

- Sator Square

- Vedic square

- Word square

Notes

- ↑ Busby, Mattha (27 June 2020). "Cambridge college to remove window commemorating eugenicist". http://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/jun/27/cambridge-gonville-caius-college-eugenicist-window-ronald-fisher.

- ↑ Wallis, W. D.; George, J. C. (2011). Introduction to Combinatorics. CRC Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-4398-0623-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=PTbb7x-mI5gC&pg=PA212.

- ↑ (Euler, 1782), pp. 90-91. From p. 90: "Pour cet effect nous reprenons le quarré latin fondamentel, qui, en omettant les exponsans, aura la forme suivante: …" (For this purpose, we take the fundamental Latin square, which, by omitting the exponents, will have the following form: …) From p. 91: "§.8 Ayant donc établi ce quarré latin, … " (§.8 Having thus established this Latin square, … ")

- ↑ Euler, Leonhard (1782). "Recherches sur une nouvelle espèce de quarrés magiques" (in French). Verhandelingen Uitgegeven Door Het Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen te Vlissingen (Proceedings Published by the Zeeland Society of Sciences in Flushing [, Netherlands]) 9: 85–239. https://books.google.com/books?id=VA4VAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA1-PA85. (Note: Euler first presented this memoir to the Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg, Russia on 8 March 1779.)

- ↑ Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007) (in en). Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 12. ISBN 9781420010541. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q9jLBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA12. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Small Latin squares, quasigroups, and loops". Journal of Combinatorial Designs 15 (2): 98–119. 2007. doi:10.1002/jcd.20105.

- ↑ Euler, L. (1782). "Recherches sur une nouvelle espèce de quarrés magiques". Verhandelingen/Uitgegeven Door Het Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen te Vlissingen (9): 85–239.

- ↑ Cayley, A. (1890). "On Latin Squares". Oxford Camb. Dublin Messenger of Math. 19: 85–239.

- ↑ MacMahon, P.A. (1915). Combinatory Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 300.

- ↑ Frolov, M. (1890). "Sur les permutations carrées". J. De Math. Spéc. IV: 8–11, 25–30.

- ↑ Tarry, Gaston (1900). "Le Probléme de 36 Officiers". Compte Rendu de l'Association Française pour l'Avancement des Sciences (Secrétariat de l'Association) 1: 122–123.

- ↑ Tarry, Gaston (1901). "Le Probléme de 36 Officiers". Compte Rendu de l'Association Française pour l'Avancement des Sciences (Secrétariat de l'Association) 2: 170–203.

- ↑ Fisher, R.A.; Yates, F. (1934). "The 6 × 6 Latin squares". Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 30 (4): 492–507. doi:10.1017/S0305004100012731. Bibcode: 1934PCPS...30..492F.

- ↑ Schönhardt, E. (1930). "Über lateinische Quadrate und Unionen". J. Reine Angew. Math. 1930 (163): 183–230. doi:10.1515/crll.1930.163.183.

- ↑ Norton, H.W. (1939). "The 7 × 7 squares". Annals of Eugenics 9 (3): 269–307. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1939.tb02214.x.

- ↑ Sade, A. (1951). "An omission in Norton's list of 7 × 7 squares". Ann. Math. Stat. 22 (2): 306–307. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177729654.

- ↑ Saxena, P.N. (1951). "A simplified method of enumerating Latin squares by MacMahon's differential operators; II. The 7 × 7 Latin squares". J. Indian Soc. Agric. Statistics 3: 24–79.

- ↑ Preece, D.A. (1966). "Classifying Youden rectangles". J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B 28: 118–130. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1966.tb00625.x.

- ↑ Brown, J.W. (1968). "Enumeration of Latin squares with application to order 8". Journal of Combinatorial Theory 5 (2): 177–184. doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(68)80053-5.

- ↑ Wells, M.B. (1967). "The number of Latin squares of order eight". Journal of Combinatorial Theory 3: 98–99. doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(67)80021-8.

- ↑ Kolesova, G.; Lam, C.W.H.; Thiel, L. (1990). "On the number of 8 × 8 Latin squares". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 54: 143–148. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(90)90015-O.

- ↑ Bammel, S.E.; Rothstein, J. (1975). "The number of 9 × 9 Latin squares". Discrete Mathematics 11: 93–95. doi:10.1016/0012-365X(75)90108-9.

- ↑ McKay, B.D.; Rogoyski, E. (1995). "Latin squares of order ten". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics 2: 4. doi:10.37236/1222.

- ↑ McKay, B.D.; Wanless, I.M. (2005). "On the number of Latin squares". Ann. Comb. 9 (3): 335–344. doi:10.1007/s00026-005-0261-7.

- ↑ Dénes & Keedwell 1974, p. 128

- ↑ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, p. 136

- ↑ Dénes & Keedwell 1974, p. 24

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Dénes & Keedwell 1974, p. 126

- ↑ van Lint & Wilson 1992, pp. 161-162

- ↑ Jia-yu Shao; Wan-di Wei (1992). "A formula for the number of Latin squares". Discrete Mathematics 110 (1–3): 293–296. doi:10.1016/0012-365x(92)90722-r.

- ↑ Gyarfas, Andras; Sarkozy, Gabor N. (2012). "Rainbow matchings and partial transversals of Latin squares". arXiv:1208.5670 [CO math. CO].

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Aharoni, Ron; Berger, Eli; Kotlar, Dani; Ziv, Ran (2017-01-04). "On a conjecture of Stein". Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universität Hamburg 87 (2): 203–211. doi:10.1007/s12188-016-0160-3. ISSN 0025-5858.

- ↑ Stein, Sherman (1975-08-01). "Transversals of Latin squares and their generalizations". Pacific Journal of Mathematics 59 (2): 567–575. doi:10.2140/pjm.1975.59.567. ISSN 0030-8730.

- ↑ Koksma, Klaas K. (1969-07-01). "A lower bound for the order of a partial transversal in a latin square". Journal of Combinatorial Theory 7 (1): 94–95. doi:10.1016/s0021-9800(69)80009-8. ISSN 0021-9800.

- ↑ Woolbright, David E (1978-03-01). "An n × n Latin square has a transversal with at least n−n distinct symbols". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 24 (2): 235–237. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(78)90009-2. ISSN 0097-3165.

- ↑ Hatami, Pooya; Shor, Peter W. (2008-10-01). "A lower bound for the length of a partial transversal in a Latin square". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 115 (7): 1103–1113. doi:10.1016/j.jcta.2008.01.002. ISSN 0097-3165.

- ↑ Keevash, Peter; Pokrovskiy, Alexey; Sudakov, Benny; Yepremyan, Liana (2022-04-15). "New bounds for Ryser's conjecture and related problems" (in en). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, Series B 9 (8): 288–321. doi:10.1090/btran/92. ISSN 2330-0000. https://www.ams.org/btran/2022-09-08/S2330-0000-2022-00092-3/.

- ↑ Montgomery, Richard (2023). "A proof of the Ryser-Brualdi-Stein conjecture for large even n". arXiv:2310.19779 [math.CO].

- ↑ Jacobson, M. T.; Matthews, P. (1996). "Generating uniformly distributed random latin squares". Journal of Combinatorial Designs 4 (6): 405–437. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6610(1996)4:6<405::aid-jcd3>3.0.co;2-j.

- ↑ Bailey, R.A. (2008). "6 Row-Column designs and 9 More about Latin squares". Design of Comparative Experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.maths.qmul.ac.uk/~rab/DOEbook.

- ↑ Shah, Kirti R.; Sinha, Bikas K. (1989). "4 Row-Column Designs". Theory of Optimal Designs. Lecture Notes in Statistics. 54. Springer-Verlag. pp. 66–84. ISBN 0-387-96991-8.

- ↑ Colbourn, C.J.; Kløve, T.; Ling, A.C.H. (2004). "Permutation arrays for powerline communication". IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 50: 1289–1291. doi:10.1109/tit.2004.828150.

- ↑ Euler's revolution, New Scientist, 24 March 2007, pp 48–51

- ↑ Huczynska, Sophie (2006). "Powerline communication and the 36 officers problem". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 364 (1849): 3199–3214. doi:10.1098/rsta.2006.1885. PMID 17090455. Bibcode: 2006RSPTA.364.3199H.

- ↑ C. Colbourn (1984). "The complexity of completing partial latin squares". Discrete Applied Mathematics 8: 25–30. doi:10.1016/0166-218X(84)90075-1.

- ↑ "The application of Latin square in agronomic research". http://joas.agrif.bg.ac.rs/archive/article/59.

- ↑ "Letters Patent Confering the SSC Arms". ssc.ca. http://www.ssc.ca/archive/main/about/history/arms_e.html.

- ↑ The International Biometric Society

References

- Bailey, R.A. (2008). "6 Row-Column designs and 9 More about Latin squares". Design of Comparative Experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.maths.qmul.ac.uk/~rab/DOEbook.

- Dénes, J.; Keedwell, A. D. (1974). Latin squares and their applications. New York-London: Academic Press. pp. 547. ISBN 0-12-209350-X.

- Shah, Kirti R.; Sinha, Bikas K. (1989). "4 Row-Column Designs". Theory of Optimal Designs. Lecture Notes in Statistics. 54. Springer-Verlag. pp. 66–84. ISBN 0-387-96991-8.

- van Lint, J. H.; Wilson, R. M. (1992). A Course in Combinatorics. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 0-521-42260-4. https://archive.org/details/coursecombinator00lint_417.

Further reading

- Dénes, J. H.; Keedwell, A. D. (1991). Latin squares: New developments in the theory and applications. Annals of Discrete Mathematics. 46. Paul Erdős (foreword). Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 0-444-88899-3.

- Hinkelmann, Klaus; Kempthorne, Oscar (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments. I, II (Second ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-38551-7. http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-0470385510.html.

- Hinkelmann, Klaus; Kempthorne, Oscar (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (Second ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC.

- Hinkelmann, Klaus; Kempthorne, Oscar (2005). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume 2: Advanced Experimental Design (First ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-55177-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=GiYc5nRVKf8C.

- Knuth, Donald (2011). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4A: Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 1. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-03804-0.

- Laywine, Charles F.; Mullen, Gary L. (1998). Discrete mathematics using Latin squares. Wiley-Interscience Series in Discrete Mathematics and Optimization. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0-471-24064-8.

- Shah, K. R.; Sinha, Bikas K. (1996). "Row-column designs". in S. Ghosh and C. R. Rao. Design and analysis of experiments. Handbook of Statistics. 13. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co.. pp. 903–937. ISBN 0-444-82061-2.

- Raghavarao, Damaraju (1988). Constructions and Combinatorial Problems in Design of Experiments (corrected reprint of the 1971 Wiley ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-65685-3. https://archive.org/details/constructionscom0000ragh.

- Street, Anne Penfold; Street, Deborah J. (1987). Combinatorics of Experimental Design. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-853256-3.

- Berger, Paul D.; Maurer, Robert E.; Celli, Giovana B. (November 28, 2017). Experimental Design with Applications in Management, Engineering, and the Sciences (2nd edition (November 28, 2017) ed.). Springer. pp. 267–282.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Latin Square". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/LatinSquare.html.

- Latin Squares in the Encyclopaedia of Mathematics

- Latin Squares in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences

|