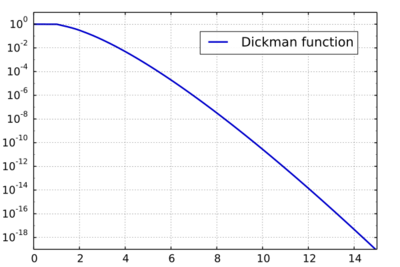

Dickman function

In analytic number theory, the Dickman function or Dickman–de Bruijn function ρ is a special function used to estimate the proportion of smooth numbers up to a given bound. It was first studied by actuary Karl Dickman, who defined it in his only mathematical publication.[1] It was later studied by the Dutch mathematician Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn.[2][3]

Definition

The Dickman–de Bruijn function is a continuous function that satisfies the delay differential equation

with initial conditions for 0 ≤ u ≤ 1.

Properties

Dickman proved that, when is fixed, we have

where is the number of y-smooth (or y-friable) integers below x. Equivalently, the number of -smooth numbers less than is about

Ramaswami later gave a rigorous proof that for fixed a, was asymptotic to , with the error bound

Knuth gives a proof for a narrowed bound:

where γ is Euler's constant.[5]: 98

Applications

The main purpose of the Dickman–de Bruijn function is to estimate the frequency of smooth numbers at a given size. This can be used to optimize various number-theoretical algorithms such as P–1 factoring and can be useful of its own right.[5]

It can be shown that[6]

which is related to the estimate below.

The Golomb–Dickman constant has an alternate definition in terms of the Dickman–de Bruijn function.

Estimation

A first approximation might be A better estimate is[7]

where Ei is the exponential integral and ξ is the positive root of

A simple upper bound is

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 3.0685282×10−1 |

| 3 | 4.8608388×10−2 |

| 4 | 4.9109256×10−3 |

| 5 | 3.5472470×10−4 |

| 6 | 1.9649696×10−5 |

| 7 | 8.7456700×10−7 |

| 8 | 3.2320693×10−8 |

| 9 | 1.0162483×10−9 |

| 10 | 2.7701718×10−11 |

Computation

For each interval [n − 1, n] with n an integer, there is an analytic function such that . For 0 ≤ u ≤ 1, . For 1 ≤ u ≤ 2, . For 2 ≤ u ≤ 3,

with Li2 the dilogarithm. Other can be calculated using infinite series.[8]

An alternate method is computing lower and upper bounds with the trapezoidal rule;[7] a mesh of progressively finer sizes allows for arbitrary accuracy. For high precision calculations (hundreds of digits), a recursive series expansion about the midpoints of the intervals is superior.[9] Values for u ≤ 7 can be usefully computed via numerical integration in ordinary double-precision floating-point.[5]: 99

Extension

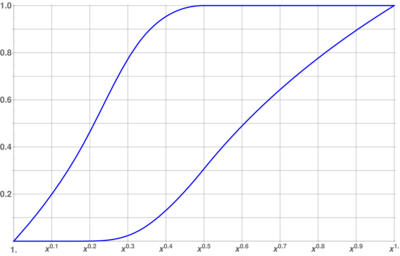

Friedlander defines a two-dimensional analog of .[10] This function is used to estimate a function similar to de Bruijn's, but counting the number of y-smooth integers with at most one prime factor greater than z. Then

This class of numbers may be encountered in the two-stage variant of P-1 factoring. However, Kruppa's estimate of the probability of finding a factor by P-1 does not make use of this result.[5]: 100

See also

- Buchstab function, a function used similarly to estimate the number of rough numbers, whose convergence to is controlled by the Dickman function

- Golomb–Dickman constant

- Poisson-Dirichlet distribution

References

- ↑ Dickman, K. (1930). "On the frequency of numbers containing prime factors of a certain relative magnitude". Arkiv för Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik 22A (10): 1–14. Bibcode: 1930ArMAF..22A..10D. Dickman's paper is difficult to access; for alternatives, see nt.number theory - Reference request: Dickman, On the frequency of numbers containing prime factors.

- ↑ de Bruijn, N. G. (1951). "On the number of positive integers ≤ x and free of prime factors > y". Indagationes Mathematicae 13: 50–60. http://alexandria.tue.nl/repository/freearticles/597499.pdf.

- ↑ de Bruijn, N. G. (1966). "On the number of positive integers ≤ x and free of prime factors > y, II". Indagationes Mathematicae 28: 239–247. http://alexandria.tue.nl/repository/freearticles/597534.pdf.

- ↑ Ramaswami, V. (1949). "On the number of positive integers less than and free of prime divisors greater than xc". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 55 (12): 1122–1127. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1949-09337-0. https://www.ams.org/bull/1949-55-12/S0002-9904-1949-09337-0/S0002-9904-1949-09337-0.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kruppa, Alexander (2010). Speeding up Integer Multiplication and Factorization (PDF) (PhD thesis). Henri Poincaré University. – Work describes algorithms that Kruppa had contributed to GMP-ECM and other factoring programs. Some chapters have been published elsewhere.

- ↑ Hildebrand, A.; Tenenbaum, G. (1993). "Integers without large prime factors". Journal de théorie des nombres de Bordeaux 5 (2): 411–484. doi:10.5802/jtnb.101. http://archive.numdam.org/article/JTNB_1993__5_2_411_0.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 van de Lune, J.; Wattel, E. (1969). "On the Numerical Solution of a Differential-Difference Equation Arising in Analytic Number Theory". Mathematics of Computation 23 (106): 417–421. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1969-0247789-3.

- ↑ Bach, Eric; Peralta, René (1996). "Asymptotic Semismoothness Probabilities". Mathematics of Computation 65 (216): 1701–1715. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-96-00775-2. Bibcode: 1996MaCom..65.1701B. http://cr.yp.to/bib/1996/bach-semismooth.pdf.

- ↑ Marsaglia, George; Zaman, Arif; Marsaglia, John C. W. (1989). "Numerical Solution of Some Classical Differential-Difference Equations". Mathematics of Computation 53 (187): 191–201. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1989-0969490-3.

- ↑ Friedlander, John B. (1976). "Integers free from large and small primes". Proc. London Math. Soc. 33 (3): 565–576. doi:10.1112/plms/s3-33.3.565.

Further reading

- Broadhurst, David (2010). "Dickman polylogarithms and their constants". arXiv:1004.0519 [math-ph].

- Soundararajan, Kannan (2012). "An asymptotic expansion related to the Dickman function". Ramanujan Journal 29 (1–3): 25–30. doi:10.1007/s11139-011-9304-3.

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Dickman function". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/DickmanFunction.html.

|