Differentiation of trigonometric functions

| Trigonometry |

|---|

|

| Reference |

| Laws and theorems |

| Calculus |

| Function | Derivative |

|---|---|

The differentiation of trigonometric functions is the mathematical process of finding the derivative of a trigonometric function, or its rate of change with respect to a variable. For example, the derivative of the sine function is written sin′(a) = cos(a), meaning that the rate of change of sin(x) at a particular angle x = a is given by the cosine of that angle.

All derivatives of circular trigonometric functions can be found from those of sin(x) and cos(x) by means of the quotient rule applied to functions such as tan(x) = sin(x)/cos(x). Knowing these derivatives, the derivatives of the inverse trigonometric functions are found using implicit differentiation.

Proofs of derivatives of trigonometric functions

Limit of sin(θ)/θ as θ tends to 0

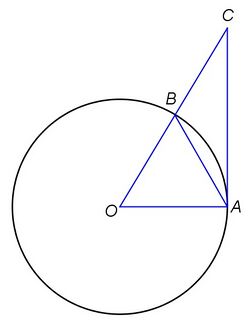

The diagram at right shows a circle with centre O and radius r = 1. Let two radii OA and OB make an arc of θ radians. Since we are considering the limit as θ tends to zero, we may assume θ is a small positive number, say 0 < θ < 1/2 π in the first quadrant.

In the diagram, let R1 be the triangle OAB, R2 the circular sector OAB, and R3 the triangle OAC.

The area of triangle OAB is:

The area of the circular sector OAB is:

The area of the triangle OAC is given by:

Since each region is contained in the next, one has:

Moreover, since sin θ > 0 in the first quadrant, we may divide through by 1/2 sin θ, giving:

In the last step we took the reciprocals of the three positive terms, reversing the inequities.

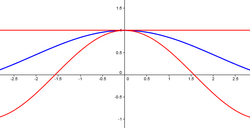

We conclude that for 0 < θ < 1/2 π, the quantity sin(θ)/θ is always less than 1 and always greater than cos(θ). Thus, as θ gets closer to 0, sin(θ)/θ is "squeezed" between a ceiling at height 1 and a floor at height cos θ, which rises towards 1; hence sin(θ)/θ must tend to 1 as θ tends to 0 from the positive side:

For the case where θ is a small negative number –1/2 π < θ < 0, we use the fact that sine is an odd function:

Limit of (cos(θ)-1)/θ as θ tends to 0

The last section enables us to calculate this new limit relatively easily. This is done by employing a simple trick. In this calculation, the sign of θ is unimportant.

Using cos2θ – 1 = –sin2θ, the fact that the limit of a product is the product of limits, and the limit result from the previous section, we find that:

Limit of tan(θ)/θ as θ tends to 0

Using the limit for the sine function, the fact that the tangent function is odd, and the fact that the limit of a product is the product of limits, we find:

Derivative of the sine function

We calculate the derivative of the sine function from the limit definition:

Using the angle addition formula sin(α+β) = sin α cos β + sin β cos α, we have:

Using the limits for the sine and for the cosine functions:

Derivative of the cosine function

From the definition of derivative

We again calculate the derivative of the cosine function from the limit definition:

Using the angle addition formula cos(α+β) = cos α cos β – sin α sin β, we have:

Using the limits for the sine and cosine functions:

From the chain rule

To compute the derivative of the cosine function from the chain rule, first observe the following three facts:

The first and the second are trigonometric identities, and the third is proven above. Using these three facts, we can write the following,

We can differentiate this using the chain rule. Letting , we have:

- .

Therefore, we have proven that

- .

Derivative of the tangent function

From the definition of derivative

To calculate the derivative of the tangent function tan θ, we use first principles. By definition:

Using the well-known angle formula tan(α+β) = (tan α + tan β) / (1 - tan α tan β), we have:

Using the fact that the limit of a product is the product of the limits:

Using the limit for the tangent function, and the fact that tan δ tends to 0 as δ tends to 0:

We see immediately that:

From the quotient rule

One can also compute the derivative of the tangent function using the quotient rule.

The numerator can be simplified to 1 by the Pythagorean identity, giving us,

Therefore,

Proofs of derivatives of inverse trigonometric functions

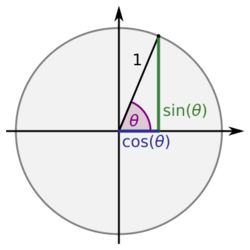

The following derivatives are found by setting a variable y equal to the inverse trigonometric function that we wish to take the derivative of. Using implicit differentiation and then solving for dy/dx, the derivative of the inverse function is found in terms of y. To convert dy/dx back into being in terms of x, we can draw a reference triangle on the unit circle, letting θ be y. Using the Pythagorean theorem and the definition of the regular trigonometric functions, we can finally express dy/dx in terms of x.

Differentiating the inverse sine function

We let

Where

Then

Taking the derivative with respect to on both sides and solving for dy/dx:

Substituting in from above,

Substituting in from above,

Differentiating the inverse cosine function

We let

Where

Then

Taking the derivative with respect to on both sides and solving for dy/dx:

Substituting in from above, we get

Substituting in from above, we get

Alternatively, once the derivative of is established, the derivative of follows immediately by differentiating the identity so that .

Differentiating the inverse tangent function

We let

Where

Then

Taking the derivative with respect to on both sides and solving for dy/dx:

Left side:

- using the Pythagorean identity

Right side:

Therefore,

Substituting in from above, we get

Differentiating the inverse cotangent function

We let

where . Then

Taking the derivative with respect to on both sides and solving for dy/dx:

Left side:

- using the Pythagorean identity

Right side:

Therefore,

Substituting ,

Alternatively, as the derivative of is derived as shown above, then using the identity follows immediately that

Differentiating the inverse secant function

Using implicit differentiation

Let

Then

(The absolute value in the expression is necessary as the product of secant and tangent in the interval of y is always nonnegative, while the radical is always nonnegative by definition of the principal square root, so the remaining factor must also be nonnegative, which is achieved by using the absolute value of x.)

Using the chain rule

Alternatively, the derivative of arcsecant may be derived from the derivative of arccosine using the chain rule.

Let

Where

- and

Then, applying the chain rule to :

Differentiating the inverse cosecant function

Using implicit differentiation

Let

Then

(The absolute value in the expression is necessary as the product of cosecant and cotangent in the interval of y is always nonnegative, while the radical is always nonnegative by definition of the principal square root, so the remaining factor must also be nonnegative, which is achieved by using the absolute value of x.)

Using the chain rule

Alternatively, the derivative of arccosecant may be derived from the derivative of arcsine using the chain rule.

Let

Where

- and

Then, applying the chain rule to :

See also

- Calculus – Branch of mathematics

- Derivative

- Differentiation rules – Rules for computing derivatives of functions

- General Leibniz rule – Generalization of the product rule in calculus

- Inverse functions and differentiation – Calculus identity

- Linearity of differentiation – Calculus property

- List of integrals of inverse trigonometric functions – Wikipedia list article

- List of trigonometric identities

- Trigonometry – Area of geometry, about angles and lengths

References

Bibliography

- Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Edited by Abramowitz and Stegun, National Bureau of Standards, Applied Mathematics Series, 55 (1964)

|