Law of cotangents

| Trigonometry |

|---|

|

| Reference |

| Laws and theorems |

| Calculus |

In trigonometry, the law of cotangents is a relationship among the lengths of the sides of a triangle and the cotangents of the halves of the three angles.[1][2]

Just as three quantities whose equality is expressed by the law of sines are equal to the diameter of the circumscribed circle of the triangle (or to its reciprocal, depending on how the law is expressed), so also the law of cotangents relates the radius of the inscribed circle of a triangle (the inradius) to its sides and angles.

Statement

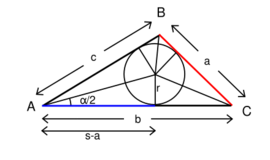

Using the usual notations for a triangle (see the figure at the upper right), where a, b, c are the lengths of the three sides, A, B, C are the vertices opposite those three respective sides, α, β, γ are the corresponding angles at those vertices, s is the semiperimeter, that is, s = a + b + c/2, and r is the radius of the inscribed circle, the law of cotangents states that

and furthermore that the inradius is given by

Proof

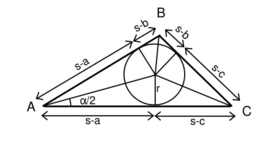

In the upper figure, the points of tangency of the incircle with the sides of the triangle break the perimeter into 6 segments, in 3 pairs. In each pair the segments are of equal length. For example, the 2 segments adjacent to vertex A are equal. If we pick one segment from each pair, their sum will be the semiperimeter s. An example of this is the segments shown in color in the figure. The two segments making up the red line add up to a, so the blue segment must be of length s − a. Obviously, the other five segments must also have lengths s − a, s − b, or s − c, as shown in the lower figure.

By inspection of the figure, using the definition of the cotangent function, we have and similarly for the other two angles, proving the first assertion.

For the second one—the inradius formula—we start from the general addition formula:

Applying to we obtain:

(This is also the triple cotangent identity.)

Substituting the values obtained in the first part, we get: Multiplying through by r3/s gives the value of r2, proving the second assertion.

Some proofs using the law of cotangents

A number of other results can be derived from the law of cotangents.

- Heron's formula. Note that the area of triangle ABC is also divided into 6 smaller triangles, also in 3 pairs, with the triangles in each pair having the same area. For example, the two triangles near vertex A, being right triangles of width s − a and height r, each have an area of 1/2r(s − a). So those two triangles together have an area of r(s − a), and the area S of the whole triangle is therefore

This gives the result as required.

- Mollweide's first formula. From the addition formula and the law of cotangents we have

This gives the result as required.

- Mollweide's second formula. From the addition formula and the law of cotangents we have

Here, an extra step is required to transform a product into a sum, according to the sum/product formula.

This gives the result

as required.

- The law of tangents can also be derived from this (Silvester 2001).

Other identities called the "law of cotangents"

The law of cotangents is not as common or well established in trigonometry as the laws of sines, cosines, or tangents, so the same name is sometimes applied to other triangle identities involving cotangents. For example:

The sum of the cotangents of two angles equals the ratio of the side between them to the altitude through the third vertex:[3]

The law of cosines can be expressed in terms of the cotangent instead of the cosine, which brings the triangle's area into the identity:[4]

Because the three angles of a triangle sum to the sum of the pairwise products of their cotangents is one:[5]

The law of cotangents may also refer to the cotangent rule in spherical trigonometry.

See also

References

- ↑ The Universal Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Pan Reference Books, 1976, page 530. English version George Allen and Unwin, 1964. Translated from the German version Meyers Rechenduden, 1960.

- ↑ It is called the 'theorem of the cotangents' in Apolinar, Efraín (2023). Illustrated glossary for school mathematics. Efrain Soto Apolinar. pp. 260–261. ISBN 9786072941311.

- ↑ Gilli, Angelo C. (1959). "F-10c. The Cotangent Law". Transistors. Prentice-Hall. pp. 266–267. https://archive.org/details/transistors0000gill/page/266/.

- ↑ Nenkov, V.; St Stefanov, H.; Velchev, A., Cosine and Cotangent Theorems for a Quadrilateral, two new Formulas for its Area and Their Applications, http://e-university.tu-sofia.bg/e-publ/files/10569_Cosine_and_cotangent_theorems_for_quadrilateral%2C_t.pdf

- ↑ Sheremet'ev, I. A. (2001). "Diophantine Laws for Nets of the Highest Symmetries". Crystallography Reports 46 (2): 161–166. doi:10.1134/1.1358386. Bibcode: 2001CryRp..46..161S. https://repo.library.stonybrook.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11401/69870/CRYv46i2final.pdf?sequence=2.

- Silvester, John R. (2001). Geometry: Ancient and Modern. Oxford University Press. pp. 313. ISBN 9780198508250.

|