Earth:Mangrullo Formation

| Mangrullo Formation Stratigraphic range: Artinskian ~286–273 Ma | |

|---|---|

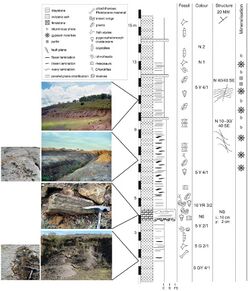

Outcrops and stratigraphic column of the Mangrullo Formation | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Cerro Largo Group |

| Underlies | Paso Aguiar Formation |

| Overlies | Frayle Muerto & Tres Islas Formations |

| Thickness | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale, limestone |

| Other | Claystone, siltstone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 32°13′S 54°07′W / 32.22°S 54.11°W |

| Paleocoordinates | [ ⚑ ] 50°12′S 37°18′W / 50.2°S 37.3°W |

| Region | Cerro Largo Department |

| Country | Uruguay |

| Extent | Norte Basin |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Mangrullo, Cerro Largo |

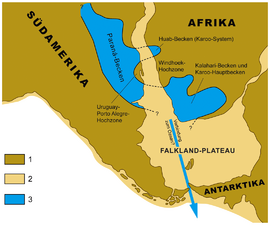

The Mangrullo Formation is a part of the Paraná Basin (Bacia do Paraná) | |

The Mangrullo Formation is an Early Permian (Artinskian) fossiliferous geological formation in northeastern Uruguay.[1][2] Some authors alternatively group it together with the Paso Aguiar Formation and the Frayle Muerto Formation as the three subdivisions of the Melo Formation, in which case it is referred to as the Mangrullo Member.[3][4] Like the correlated formations of Irati and Whitehill, it is known for its abundant mesosaur fossils. It also contains the oldest known Konservat-Lagerstätte in South America, as well as the oldest known fossils of amniote embryos.[5]

Geology

The Mangrullo Formation is part of the Cerro Largo Group of the Paraná Basin infill of South America.[5] Radiometric dating and fossil assemblage correlation with the Brazilian Irati Formation and the South African and Namibian Whitehill Formation, of the Paraná Basin and Karoo Basin respectively, puts it at around the Artinskian Age (about 279 ± 6 million years ago).[3][5]

It has a thickness of nearly 40 m (130 ft).[6] It consists primarily of beds of variable thickness of sandy and dolomitic limestone and laminated oil shale, claystone, and siltstone.[4][5]

Fossil biota

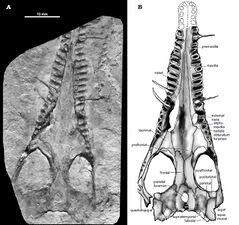

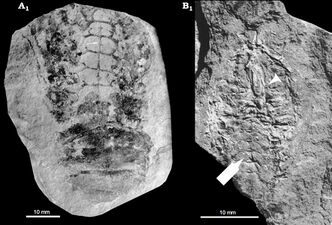

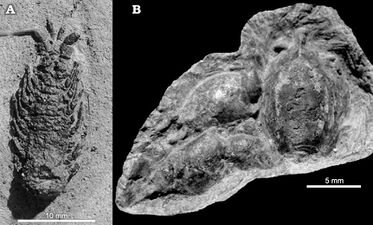

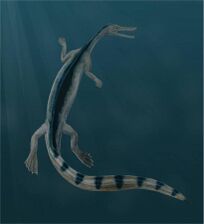

Fossil plants found in the formation include petrified wood and other remains from conifers, seed ferns (notably Gangamopteris), and various palynomorphs. Invertebrate fossils include bivalves, clam shrimp, insect wings (Hemiptera and Coleoptera of Paracicadopsis mendezalzolai, Barona arcuata and Perlapsocus formosoi),[7] pygocephalomorphs, and Chondrites. Vertebrate fossils include fragmentary remains of actinistians (coelacanths) and actinopterygians (tentatively identified as belonging to Elonichthyidae), possible ichnofossils of acanthodians (Undichna insolentia), and numerous and well-preserved skulls and partial skeletons of mesosaurs (Stereosternum and Mesosaurus).[5][8]

The Mangrullo Formation is notable for being the oldest known Konservat-Lagerstätte in South America. Fossils in some layers are exceptionally preserved, retaining details of soft tissue (including bone sutures, blood vessels, and nerves). Coprolites and gut contents of mesosaurs reveal that they preyed mainly on pygocephalomorph crustaceans and may have engaged in cannibalism. It is also the source of several fossil embryos, a hatchling, and very small mesosaurids; all of which are the oldest known evidence of amniotic ontogeny.[5][9]

Taphonomy

The locality is believed to have been a shallow lagoon-like inland sea. Its early conditions were probably estuarine or brackish, and the fossils found in the lower mudstone and claystone layers are of bioturbating invertebrates, bivalves and fish. It had an open coastal barrier to marine water but also had extensive inflow of freshwater from melting glaciers. Overlying the earlier mudstone and claystone layers is a layer of limestone deposited with noticeable rippling, an effect of wave motion on very shallow sediment. It is believed that the connection to the sea was lost and the basin gradually began to dry out, becoming more and more hypersaline as it became shallower. It produced anoxic conditions near the bottom which resulted in the exceptional preservation of fossils during this period. Most of the earlier organisms disappeared and was replaced by mesosaurs and pygocephalomorphs, both inferred to have been capable of tolerating hypersaline environments. The connection to the sea was reestablished later on in the top layers, and fossils of mesosaurs disappeared to be replaced once again by fish and bioturbating organisms.[5]

Gallery

-

Early Permian paleogeography

-

Mesosaurus tenuidens

-

M. tenuidens

-

Mesosaurid fossils

-

Mesosaurid palate

-

Mesosaurid skull

-

"Mesosaurus Sea"

-

Mesosaurid skull and description

-

Mesosaurid skeleton and gypsum

-

Pygocephalomorph (Hoplita ginsburgi) fossils

-

Pygocephalomorph fossils

-

Algal mats

See also

- List of fossil sites

- List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in Uruguay

References

- ↑ Mangrullo Formation at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Mangrullo Member at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Arroyo de La Mina (Permian of Uruguay)". Paleobiology Database. https://paleobiodb.org/classic/displayCollResults?collection_no=90863.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Beri et al., 2011

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Piñeiro et al., 2012a

- ↑ De Santa Ana et al., 2006

- ↑ Pinto et al., 2000

- ↑ Mones, 1972

- ↑ Piñeiro et al., 2012b

Bibliography

- Piñeiro, G.; Ramos, A.; Goso, C. S.; Scarabino, F.; Laurin, M. (2012a), "Unusual Environmental Conditions Preserve a Permian Mesosaur-Bearing Konservat-Lagerstätte from Uruguay", Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57 (2): 299, doi:10.4202/app.2010.0113

- Piñeiro, G.; Ferigolo, J.; Meneghel, M.; Laurin, M. (2012b), "The oldest known amniotic embryos suggest viviparity in mesosaurs", Historical Biology 24 (6): 620–630, doi:10.1080/08912963.2012.662230, Bibcode: 2012HBio...24..620P

- Beri, Á.; Gutiérrez, P.; Balarino, L. A. (2011), "Palynostratigraphy of the late Palaeozoic of Uruguay, Paraná Basin", Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 167 (1–2): 16–29, doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2011.05.004, Bibcode: 2011RPaPa.167...16B

- De Santa Ana, H.; Goso, C.; Daners, G. (2006), Cuencas Sedimentarias de Uruguay: Geología, Paleontología y Recursos Minerales, Paleozoico - Cuenca Norte: estratigrafía del Carbonífero y Pérmico, DIRAC, University of the Republic, pp. 147–208, ISBN 9789974003163

- Pinto, I. D.; Piñeiro, G.; Verde, M. (2000), "First Permian insects from Uruguay", Pesquisas 27: 89–96

- Mones, A (1972), "Lista de los vertebrados fosiles del Uruguay, I. Chondrichthyes, Osteichthyes, Reptilia, Aves - List of the fossil vertebrates of Uruguay, I. Chondrichthyes, Osteichthyes, Reptilia, Aves", Comunicaciones Paleontologicas del Museo de Historia Natural de Montevideo 1: 23–35

Template:Stratigraphic formations of Uruguay

|