Eisenstein series

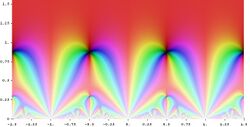

Eisenstein series, named after German mathematician Gotthold Eisenstein,[1] are particular modular forms with infinite series expansions that may be written down directly. Originally defined for the modular group, Eisenstein series can be generalized in the theory of automorphic forms.

Eisenstein series for the modular group

Let τ be a complex number with strictly positive imaginary part. Define the holomorphic Eisenstein series G2k(τ) of weight 2k, where k ≥ 2 is an integer, by the following series:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ G_{2k}(\tau) = \sum_{ (m,n)\in\Z^2\setminus\{(0,0)\}} \frac{1}{(m+n\tau )^{2k}}. }[/math]

This series absolutely converges to a holomorphic function of τ in the upper half-plane and its Fourier expansion given below shows that it extends to a holomorphic function at τ = i∞. It is a remarkable fact that the Eisenstein series is a modular form. Indeed, the key property is its SL(2, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z} }[/math])-covariance. Explicitly if a, b, c, d ∈ [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z} }[/math] and ad − bc = 1 then

- [math]\displaystyle{ G_{2k} \left( \frac{ a\tau +b}{ c\tau + d} \right) = (c\tau +d)^{2k} G_{2k}(\tau) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} G_{2k}\left(\frac{a\tau+b}{c\tau+d}\right) &= \sum_{(m,n) \in \Z^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}} \frac{1}{\left(m+n\frac{a\tau+b}{c\tau+d}\right)^{2k}} \\ &= \sum_{(m,n) \in \Z^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}} \frac{(c\tau+d)^{2k}}{(md+nb+(mc+na)\tau)^{2k}} \\ &= \sum_{\left(m',n'\right) = (m,n)\begin{pmatrix}d \ \ c\\b \ \ a\end{pmatrix}\atop (m,n)\in \Z^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}} \frac{(c\tau+d)^{2k}}{\left(m'+n'\tau\right)^{2k}} \end{align} }[/math]

If ad − bc = 1 then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix}d & c\\b & a\end{pmatrix}^{-1} = \begin{pmatrix}\ a & -c\\-b & \ d\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

so that

- [math]\displaystyle{ (m,n) \mapsto (m,n)\begin{pmatrix}d & c\\b & a\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

is a bijection [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z} }[/math]2 → [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z} }[/math]2, i.e.:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{\left(m',n'\right) = (m,n)\begin{pmatrix}d \ \ c\\b \ \ a\end{pmatrix}\atop (m,n)\in \Z^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}} \frac{1}{\left(m'+n'\tau\right)^{2k}} = \sum_{\left(m',n'\right)\in \mathbb{Z}^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}} \frac{1}{(m'+n'\tau)^{2k}} = G_{2k}(\tau) }[/math]

Overall, if ad − bc = 1 then

- [math]\displaystyle{ G_{2k}\left(\frac{a\tau+b}{c\tau+d}\right) = (c\tau+d)^{2k} G_{2k}(\tau) }[/math]

Note that k ≥ 2 is necessary such that the series converges absolutely, whereas k needs to be even otherwise the sum vanishes because the (-m, -n) and (m, n) terms cancel out. For k = 2 the series converges but it is not a modular form.

Relation to modular invariants

The modular invariants g2 and g3 of an elliptic curve are given by the first two Eisenstein series:[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} g_2 &= 60 G_4 \\ g_3 &= 140 G_6 .\end{align} }[/math]

The article on modular invariants provides expressions for these two functions in terms of theta functions.

Recurrence relation

Any holomorphic modular form for the modular group[4] can be written as a polynomial in G4 and G6. Specifically, the higher order G2k can be written in terms of G4 and G6 through a recurrence relation. Let dk = (2k + 3)k! G2k + 4, so for example, d0 = 3G4 and d1 = 5G6. Then the dk satisfy the relation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=0}^n {n \choose k} d_k d_{n-k} = \frac{2n+9}{3n+6}d_{n+2} }[/math]

for all n ≥ 0. Here, (nk) is the binomial coefficient.

The dk occur in the series expansion for the Weierstrass's elliptic functions:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \wp(z) &=\frac{1}{z^2} + z^2 \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac {d_k z^{2k}}{k!} \\ &=\frac{1}{z^2} + \sum_{k=1}^\infty (2k+1) G_{2k+2} z^{2k}. \end{align} }[/math]

Fourier series

Define q = e2πiτ. (Some older books define q to be the nome q = eπiτ, but q = e2πiτ is now standard in number theory.) Then the Fourier series of the Eisenstein[5] series is

- [math]\displaystyle{ G_{2k}(\tau) = 2\zeta(2k) \left(1+c_{2k}\sum_{n=1}^\infty \sigma_{2k-1}(n)q^n \right) }[/math]

where the coefficients c2k are given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} c_{2k} &= \frac{(2\pi i)^{2k}}{(2k-1)! \zeta(2k)} \\[4pt] &= \frac {-4k}{B_{2k}} = \frac 2 {\zeta(1-2k)}. \end{align} }[/math]

Here, Bn are the Bernoulli numbers, ζ(z) is Riemann's zeta function and σp(n) is the divisor sum function, the sum of the pth powers of the divisors of n. In particular, one has

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} G_4(\tau)&=\frac{\pi^4}{45} \left( 1+ 240\sum_{n=1}^\infty \sigma_3(n) q^{n} \right) \\[4pt] G_6(\tau)&=\frac{2\pi^6}{945} \left( 1- 504\sum_{n=1}^\infty \sigma_5(n) q^n \right). \end{align} }[/math]

The summation over q can be resummed as a Lambert series; that is, one has

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} q^n \sigma_a(n) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n^a q^n}{1-q^n} }[/math]

for arbitrary complex |q| < 1 and a. When working with the q-expansion of the Eisenstein series, this alternate notation is frequently introduced:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} E_{2k}(\tau)&=\frac{G_{2k}(\tau)}{2\zeta (2k)}\\ &= 1+\frac {2}{\zeta(1-2k)}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n^{2k-1} q^n}{1-q^n} \\ &= 1- \frac{4k}{B_{2k}}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \sigma_{2k-1}(n)q^n \\ &= 1 - \frac{4k}{B_{2k}} \sum_{d,n \geq 1} n^{2k-1} q^{nd}. \end{align} }[/math]

Identities involving Eisenstein series

As theta functions

Source:[6]

Given q = e2πiτ, let

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} E_4(\tau)&=1+240\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {n^3q^n}{1-q^n} \\ E_6(\tau)&=1-504\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {n^5q^n}{1-q^n} \\ E_8(\tau)&=1+480\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {n^7q^n}{1-q^n} \end{align} }[/math]

and define the Jacobi theta functions which normally uses the nome eπiτ,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} a&=\theta_2\left(0; e^{\pi i\tau}\right)=\vartheta_{10}(0; \tau) \\ b&=\theta_3\left(0; e^{\pi i\tau}\right)=\vartheta_{00}(0; \tau) \\ c&=\theta_4\left(0; e^{\pi i\tau}\right)=\vartheta_{01}(0; \tau) \end{align} }[/math]

where θm and ϑij are alternative notations. Then we have the symmetric relations,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} E_4(\tau)&= \tfrac{1}{2}\left(a^8+b^8+c^8\right) \\[4pt] E_6(\tau)&= \tfrac{1}{2}\sqrt{\frac{\left(a^8+b^8+c^8\right)^3-54(abc)^8}{2}} \\[4pt] E_8(\tau)&= \tfrac{1}{2}\left(a^{16}+b^{16}+c^{16}\right) = a^8b^8 +a^8c^8 +b^8c^8 \end{align} }[/math]

Basic algebra immediately implies

- [math]\displaystyle{ E_4^3-E_6^2 = \tfrac{27}{4}(abc)^8 }[/math]

an expression related to the modular discriminant,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta = g_2^3-27g_3^2 = (2\pi)^{12} \left(\tfrac{1}{2}a b c\right)^8 }[/math]

The third symmetric relation, on the other hand, is a consequence of E8 = E24 and a4 − b4 + c4 = 0.

Products of Eisenstein series

Eisenstein series form the most explicit examples of modular forms for the full modular group SL(2, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z} }[/math]). Since the space of modular forms of weight 2k has dimension 1 for 2k = 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, different products of Eisenstein series having those weights have to be equal up to a scalar multiple. In fact, we obtain the identities:[7]

- [math]\displaystyle{ E_4^2 = E_8, \quad E_4 E_6 = E_{10}, \quad E_4 E_{10} = E_{14}, \quad E_6 E_8 = E_{14}. }[/math]

Using the q-expansions of the Eisenstein series given above, they may be restated as identities involving the sums of powers of divisors:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(1+240\sum_{n=1}^\infty \sigma_3(n) q^n\right)^2 = 1+480\sum_{n=1}^\infty \sigma_7(n) q^n, }[/math]

hence

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_7(n)=\sigma_3(n)+120\sum_{m=1}^{n-1}\sigma_3(m)\sigma_3(n-m), }[/math]

and similarly for the others. The theta function of an eight-dimensional even unimodular lattice Γ is a modular form of weight 4 for the full modular group, which gives the following identities:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_\Gamma (\tau)=1+\sum_{n=1}^\infty r_{\Gamma}(2n) q^{n} = E_4(\tau), \qquad r_{\Gamma}(n) = 240\sigma_3(n) }[/math]

for the number rΓ(n) of vectors of the squared length 2n in the root lattice of the type E8.

Similar techniques involving holomorphic Eisenstein series twisted by a Dirichlet character produce formulas for the number of representations of a positive integer n' as a sum of two, four, or eight squares in terms of the divisors of n.

Using the above recurrence relation, all higher E2k can be expressed as polynomials in E4 and E6. For example:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} E_{8} &= E_4^2 \\ E_{10} &= E_4\cdot E_6 \\ 691 \cdot E_{12} &= 441\cdot E_4^3+ 250\cdot E_6^2 \\ E_{14} &= E_4^2\cdot E_6 \\ 3617\cdot E_{16} &= 1617\cdot E_4^4+ 2000\cdot E_4 \cdot E_6^2 \\ 43867 \cdot E_{18} &= 38367\cdot E_4^3\cdot E_6+5500\cdot E_6^3 \\ 174611 \cdot E_{20} &= 53361\cdot E_4^5+ 121250\cdot E_4^2\cdot E_6^2 \\ 77683 \cdot E_{22} &= 57183\cdot E_4^4\cdot E_6+20500\cdot E_4\cdot E_6^3 \\ 236364091 \cdot E_{24} &= 49679091\cdot E_4^6+ 176400000\cdot E_4^3\cdot E_6^2 + 10285000\cdot E_6^4 \end{align} }[/math]

Many relationships between products of Eisenstein series can be written in an elegant way using Hankel determinants, e.g. Garvan's identity

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\frac{\Delta}{(2\pi)^{12}}\right)^2=-\frac{691}{1728^2\cdot250}\det \begin{vmatrix}E_4&E_6&E_8\\ E_6&E_8&E_{10}\\ E_8&E_{10}&E_{12}\end{vmatrix} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta=(2\pi)^{12}\frac{E_4^3-E_6^2}{1728} }[/math]

is the modular discriminant.[8]

Ramanujan identities

Srinivasa Ramanujan gave several interesting identities between the first few Eisenstein series involving differentiation.[9] Let

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} L(q)&=1-24\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {nq^n}{1-q^n}&&=E_2(\tau) \\ M(q)&=1+240\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {n^3q^n}{1-q^n}&&=E_4(\tau) \\ N(q)&=1-504\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {n^5q^n}{1-q^n}&&=E_6(\tau), \end{align} }[/math]

then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} q\frac{dL}{dq} &= \frac {L^2-M}{12} \\ q\frac{dM}{dq} &= \frac {LM-N}{3} \\ q\frac{dN}{dq} &= \frac {LN-M^2}{2}. \end{align} }[/math]

These identities, like the identities between the series, yield arithmetical convolution identities involving the sum-of-divisor function. Following Ramanujan, to put these identities in the simplest form it is necessary to extend the domain of σp(n) to include zero, by setting

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align}\sigma_p(0) = \tfrac12\zeta(-p) \quad\Longrightarrow\quad \sigma(0) &= -\tfrac{1}{24}\\ \sigma_3(0) &= \tfrac{1}{240}\\ \sigma_5(0) &= -\tfrac{1}{504}. \end{align} }[/math]

Then, for example

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=0}^n\sigma(k)\sigma(n-k)=\tfrac5{12}\sigma_3(n)-\tfrac12n\sigma(n). }[/math]

Other identities of this type, but not directly related to the preceding relations between L, M and N functions, have been proved by Ramanujan and Giuseppe Melfi,[10][11] as for example

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sum_{k=0}^n\sigma_3(k)\sigma_3(n-k)&=\tfrac1{120}\sigma_7(n) \\ \sum_{k=0}^n\sigma(2k+1)\sigma_3(n-k)&=\tfrac1{240}\sigma_5(2n+1) \\ \sum_{k=0}^n\sigma(3k+1)\sigma(3n-3k+1)&=\tfrac19\sigma_3(3n+2). \end{align} }[/math]

Generalizations

Automorphic forms generalize the idea of modular forms for general Lie groups; and Eisenstein series generalize in a similar fashion.

Defining OK to be the ring of integers of a totally real algebraic number field K, one then defines the Hilbert–Blumenthal modular group as PSL(2,OK). One can then associate an Eisenstein series to every cusp of the Hilbert–Blumenthal modular group.

References

- ↑ "Gotthold Eisenstein - Biography" (in en). https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Eisenstein/.

- ↑ Gekeler, Ernst-Ulrich (2011). "PARA-EISENSTEIN SERIES FOR THE MODULAR GROUP GL(2, 𝔽q[T)"]. Taiwanese Journal of Mathematics 15 (4): 1463–1475. doi:10.11650/twjm/1500406358. ISSN 1027-5487. https://www.jstor.org/stable/taiwjmath.15.4.1463.

- ↑ Obers, N. A.; Pioline, B. (2000-03-07). "Eisenstein Series in String Theory". Classical and Quantum Gravity 17 (5): 1215–1224. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/17/5/330. ISSN 0264-9381.

- ↑ Mertens, Michael H.; Rolen, Larry (2015). "Lacunary recurrences for Eisenstein series". Research in Number Theory 1. doi:10.1007/s40993-015-0010-x. ISSN 2363-9555.

- ↑ Karel, Martin L. (1974). "Fourier Coefficients of Certain Eisenstein Series". Annals of Mathematics 99 (1): 176–202. doi:10.2307/1971017. ISSN 0003-486X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1971017.

- ↑ "How to prove this series identity involving Eisenstein series?" (in en). https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/4284880/how-to-prove-this-series-identity-involving-eisenstein-series.

- ↑ Dickson, Martin; Neururer, Michael (2018). "Products of Eisenstein series and Fourier expansions of modular forms at cusps". Journal of Number Theory 188: 137–164. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2017.12.013.

- ↑ Milne, Steven C. (2000). "Hankel Determinants of Eisenstein Series". arXiv:math/0009130v3. The paper uses a non-equivalent definition of [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math], but this has been accounted for in this article.

- ↑ Bhuvan, E. N.; Vasuki, K. R. (2019-06-24). "On a Ramanujan's Eisenstein series identity of level fifteen" (in en). Proceedings - Mathematical Sciences 129 (4): 57. doi:10.1007/s12044-019-0498-4. ISSN 0973-7685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12044-019-0498-4.

- ↑ Ramanujan, Srinivasa (1962). "On certain arithmetical functions". Collected Papers. New York, NY: Chelsea. pp. 136–162.

- ↑ Melfi, Giuseppe (1998). "On some modular identities". Number Theory, Diophantine, Computational and Algebraic Aspects: Proceedings of the International Conference held in Eger, Hungary. Walter de Grutyer & Co.. pp. 371–382.

Further reading

- Akhiezer, Naum Illyich (1970) (in Russian). Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions. Moscow. Translated into English as Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions. AMS Translations of Mathematical Monographs 79. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. 1990. ISBN 0-8218-4532-2.

- Apostol, Tom M. (1990). Modular Functions and Dirichlet Series in Number Theory (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 0-387-97127-0. https://archive.org/details/modularfunctions0000apos.

- Chan, Heng Huat; Ong, Yau Lin (1999). "On Eisenstein Series". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 127 (6): 1735–1744. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-99-04832-7. https://www.ams.org/proc/1999-127-06/S0002-9939-99-04832-7/S0002-9939-99-04832-7.pdf.

- Iwaniec, Henryk (2002). Spectral Methods of Automorphic Forms. Graduate Studies in Mathematics 53 (2nd ed.). Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ch. 3. ISBN 0-8218-3160-7.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1973). A Course in Arithmetic. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 7 (transl. ed.). New York & Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9780387900407. https://archive.org/details/courseinarithmet00serr.

|