Theta function

In mathematics, theta functions are special functions of several complex variables. They show up in many topics, including Abelian varieties, moduli spaces, quadratic forms, and solitons. As Grassmann algebras, they appear in quantum field theory.[1]

The most common form of theta function is that occurring in the theory of elliptic functions. With respect to one of the complex variables (conventionally called z), a theta function has a property expressing its behavior with respect to the addition of a period of the associated elliptic functions, making it a quasiperiodic function. In the abstract theory this quasiperiodicity comes from the cohomology class of a line bundle on a complex torus, a condition of descent.

One interpretation of theta functions when dealing with the heat equation is that "a theta function is a special function that describes the evolution of temperature on a segment domain subject to certain boundary conditions".[2]

Throughout this article, should be interpreted as (in order to resolve issues of choice of branch).[note 1]

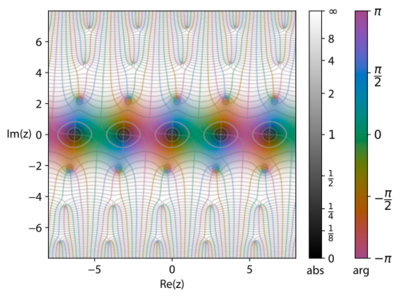

Jacobi theta function

There are several closely related functions called Jacobi theta functions, and many different and incompatible systems of notation for them. One Jacobi theta function (named after Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi) is a function defined for two complex variables z and τ, where z can be any complex number and τ is the half-period ratio, confined to the upper half-plane, which means it has positive imaginary part. It is given by the formula

where q = exp(πiτ) is the nome and η = exp(2πiz). It is a Jacobi form. The restriction ensures that it is an absolutely convergent series. At fixed τ, this is a Fourier series for a 1-periodic entire function of z. Accordingly, the theta function is 1-periodic in z:

By completing the square, it is also τ-quasiperiodic in z, with

Thus, in general,

for any integers a and b.

For any fixed , the function is an entire function on the complex plane, so by Liouville's theorem, it cannot be doubly periodic in unless it is constant, and so the best we could do is to make it periodic in and quasi-periodic in . Indeed, since and , the function is unbounded, as required by Liouville's theorem.

It is in fact the most general entire function with 2 quasi-periods, in the following sense:[3]

Theorem — If is entire and nonconstant, and satisfies the functional equations for some constant .

If , then and . If , then for some nonzero .

Auxiliary functions

The Jacobi theta function defined above is sometimes considered along with three auxiliary theta functions, in which case it is written with a double 0 subscript:

The auxiliary (or half-period) functions are defined by

This notation follows Riemann and Mumford; Jacobi's original formulation was in terms of the nome q = eiπτ rather than τ. In Jacobi's notation the θ-functions are written:

The above definitions of the Jacobi theta functions are by no means unique. See Jacobi theta functions (notational variations) for further discussion.

If we set z = 0 in the above theta functions, we obtain four functions of τ only, defined on the upper half-plane. These functions are called Theta Nullwert functions, based on the German term for zero value because of the annullation of the left entry in the theta function expression. Alternatively, we obtain four functions of q only, defined on the unit disk . They are sometimes called theta constants:[note 2]

with the nome q = eiπτ. Observe that . These can be used to define a variety of modular forms, and to parametrize certain curves; in particular, the Jacobi identity is

or equivalently,

which is the Fermat curve of degree four.

Elliptic nome

Definition and identities to the theta functions

Since the Jacobi functions are defined in terms of the elliptic modulus , we need to invert this and find in terms of . We start from , the complementary modulus. As a function of it is

Let us define the elliptic nome and the complete elliptic integral of the first kind:

These identites[4][5] exist between the elliptic integral K, the modulus k, the nome q function and the theta functions:

These are two identical definitions of the complete elliptic integral of the first kind:

An identical definition of the nome function can be produced by using a series. Following function has this identity:

By solving this function after q we get this[6][7][8] result:

Karl Heinrich Schellbach wrote his derivation of this number sequence in his work Die Lehre von den elliptischen Integralen und den Thetafunktionen on page 60 down. He figured these coefficients of the fourth root of the elliptic nome out by doing substitution calculations.

The Schellbach Schwarz numbers are in the numerators and the doubles of the powers of sixteen are in the denominators.

In relation to this following limits are valid:

This table[9][10] shows numbers of the Schellbach Schwarz integer sequence A002103 accurately:

| Sc(1) | Sc(2) | Sc(3) | Sc(4) | Sc(5) | Sc(6) | Sc(7) | Sc(8) |

| 1 | 2 | 15 | 150 | 1707 | 20910 | 268616 | 3567400 |

Elliptic integer sequences

The Silesian German mathematician Hermann Amandus Schwarz wrote in his work Formeln und Lehrsätze zum Gebrauche der elliptischen Funktionen in the chapter Berechnung der Grösse k on pages 54 to 56 the described integer number sequence that was researched by Karl Heinrich Schellbach too. Furthermore, his Schellbach Schwarz number sequence Sc(n) was analyzed by the mathematicians Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass and Louis Melville Milne-Thomson in the 20th century. The mathematician Adolf Kneser determined a synthesis method for this sequence based on the following pattern:

The mathematician Karl Heinrich Schellbach also researched this integer sequence relation and in his work Die Lehre von den elliptischen Integralen und den Thetafunktionen[11] he dealt with it in detail. The Schellbach Schwarz sequence Sc(n) is entered in the online encyclopedia of number sequences under the number A002103 and the Kneser sequence Kn(n) is entered under the number A227503. The Kneser integer sequence Kn(n) can be constructed in this way:

Executed examples:

The Kneser sequence appears in the Taylor series of the period ratio (half period ratio):

The derivative of this equation after leads to this equation that shows the generating function of the Kneser number sequence:

This result appears because of the Legendre's relation in the numerator.

Following table contains the Schellbach Schwarz numbers and the Kneser numbers and the Apery numbers:

| Index n | Kn(n) (A227503) | Sc(n) (A002103) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 13 | 2 |

| 3 | 184 | 15 |

| 4 | 2701 | 150 |

| 5 | 40456 | 1707 |

| 6 | 613720 | 20910 |

| 7 | 9391936 | 268616 |

| 8 | 144644749 | 3567400 |

This is the mentioned pattern formula for the Schellbach Schwarz number sequence:

In the following, it will be shown as an example how the Schellbach Schwarz numbers are built up successively. For this, the examples with the numbers Sc(4) = 150, Sc(5) = 1707 and Sc(6) = 20910 are used:

Jacobi identities

Jacobi's identities describe how theta functions transform under the modular group, which is generated by τ ↦ τ + 1 and τ ↦ −1/τ. Equations for the first transform are easily found since adding one to τ in the exponent has the same effect as adding 1/2 to z (n ≡ n2 mod 2). For the second, let

Then

Theta functions in terms of the nome

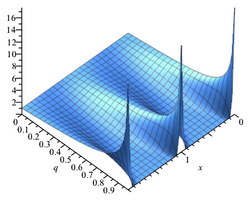

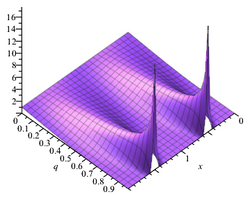

Instead of expressing the Theta functions in terms of z and τ, we may express them in terms of arguments w and the nome q, where w = eπiz and q = eπiτ. In this form, the functions become

We see that the theta functions can also be defined in terms of w and q, without a direct reference to the exponential function. These formulas can, therefore, be used to define the Theta functions over other fields where the exponential function might not be everywhere defined, such as fields of p-adic numbers.

Product representations

The Jacobi triple product (a special case of the Macdonald identities) tells us that for complex numbers w and q with |q| < 1 and w ≠ 0 we have

It can be proven by elementary means, as for instance in Hardy and Wright's An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers.

If we express the theta function in terms of the nome q = eπiτ (noting some authors instead set q = e2πiτ) and take w = eπiz then

We therefore obtain a product formula for the theta function in the form

In terms of w and q:

where ( ; )∞ is the q-Pochhammer symbol and θ( ; ) is the q-theta function. Expanding terms out, the Jacobi triple product can also be written

which we may also write as

This form is valid in general but clearly is of particular interest when z is real. Similar product formulas for the auxiliary theta functions are

In particular, so we may interpret them as one-parameter deformations of the periodic functions , again validating the interpretation of the theta function as the most general 2 quasi-period function.

Integral representations

The Jacobi theta functions have the following integral representations:

The Theta Nullwert function as this integral identity:

This formula was discussed in the essay Square series generating function transformations by the mathematician Maxie Schmidt from Georgia in Atlanta.

Based on this formula following three eminent examples are given:

Furthermore, the theta examples and shall be displayed:

Explicit values

Lemniscatic values

Proper credit for most of these results goes to Ramanujan. See Ramanujan's lost notebook and a relevant reference at Euler function. The Ramanujan results quoted at Euler function plus a few elementary operations give the results below, so they are either in Ramanujan's lost notebook or follow immediately from it. See also Yi (2004).[12] Define,

with the nome and Dedekind eta function Then for

If the reciprocal of the Gelfond constant is raised to the power of the reciprocal of an odd number, then the corresponding values or values can be represented in a simplified way by using the hyperbolic lemniscatic sine:

With the letter the Lemniscate constant is represented.

Note that the following modular identities hold:

where is the Rogers–Ramanujan continued fraction:

Equianharmonic values

The mathematician Bruce Berndt found out further values[13] of the theta function:

Further values

Many values of the theta function[14] and especially of the shown phi function can be represented in terms of the gamma function:

Nome power theorems

Direct power theorems

For the transformation of the nome[15] in the theta functions these formulas can be used:

The squares of the three theta zero-value functions with the square function as the inner function are also formed in the pattern of the Pythagorean triples according to the Jacobi Identity. Furthermore, those transformations are valid:

These formulas can be used to compute the theta values of the cube of the nome:

And the following formulas can be used to compute the theta values of the fifth power of the nome:

Transformation at the cube root of the nome

The formulas for the theta Nullwert function values from the cube root of the elliptic nome are obtained by contrasting the two real solutions of the corresponding quartic equations:

Transformation at the fifth root of the nome

The Rogers-Ramanujan continued fraction can be defined in terms of the Jacobi theta function in the following way:

The alternating Rogers-Ramanujan continued fraction function S(q) has the following two identities:

The theta function values from the fifth root of the nome can be represented as a rational combination of the continued fractions R and S and the theta function values from the fifth power of the nome and the nome itself. The following four equations are valid for all values q between 0 and 1:

Modulus dependent theorems

Im combination with the elliptic modulus, following formulas can be displayed:

These are the formulas for the square of the elliptic nome:

And this is an efficient formula for the cube of the nome:

For all real values the now mentioned formula is valid.

And for this fomula two examples shall be given:

First calculation example with the value inserted:

Second calculation example with the value inserted:

The constant represents the Golden ratio number exactly.

Some series identities

Sums with theta function in the result

The infinite sum[16][17] of the reciprocals of Fibonacci numbers with odd indices has this identity:

By not using the theta function expression, following identity between two sums can be formulated:

Also in this case is Golden ratio number again.

Infinite sum of the reciprocals of the Fibonacci number squares:

Infinite sum of the reciprocals of the Pell numbers with odd indices:

Sums with theta function in the summand

The next two series identities were proved by István Mező:[18]

These relations hold for all 0 < q < 1. Specializing the values of q, we have the next parameter free sums

Zeros of the Jacobi theta functions

All zeros of the Jacobi theta functions are simple zeros and are given by the following:

where m, n are arbitrary integers.

Relation to the Riemann zeta function

The relation

was used by Riemann to prove the functional equation for the Riemann zeta function, by means of the Mellin transform

which can be shown to be invariant under substitution of s by 1 − s. The corresponding integral for z ≠ 0 is given in the article on the Hurwitz zeta function.

Relation to the Weierstrass elliptic function

The theta function was used by Jacobi to construct (in a form adapted to easy calculation) his elliptic functions as the quotients of the above four theta functions, and could have been used by him to construct Weierstrass's elliptic functions also, since

where the second derivative is with respect to z and the constant c is defined so that the Laurent expansion of ℘(z) at z = 0 has zero constant term.

Relation to the q-gamma function

The fourth theta function – and thus the others too – is intimately connected to the Jackson q-gamma function via the relation[19]

Relations to Dedekind eta function

Let η(τ) be the Dedekind eta function, and the argument of the theta function as the nome q = eπiτ. Then,

and,

See also the Weber modular functions.

Elliptic modulus

The elliptic modulus is

and the complementary elliptic modulus is

Derivatives of theta functions

These are two identical definitions of the complete elliptic integral of the second kind:

The derivatives of the Theta Nullwert functions have these MacLaurin series:

The derivatives of theta zero-value functions[20] are as follows:

The two last mentioned formulas are valid for all real numbers of the real definition interval:

And these two last named theta derivative functions are related to each other in this way:

The derivatives of the quotients from two of the three theta functions mentioned here always have a rational relationship to those three functions:

For the derivation of these derivation formulas see the articles Nome (mathematics) and Modular lambda function!

Integrals of theta functions

For the theta functions these integrals[21] are valid:

The final results now shown are based on the general Cauchy sum formulas.

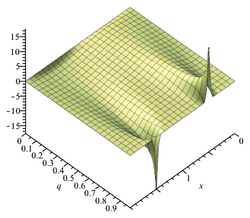

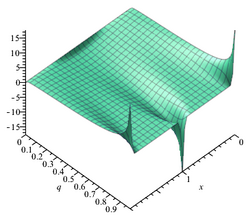

A solution to the heat equation

We take the Jacobi theta function definition by Edmund Taylor Whittaker and George Neville Watson[22][23][24] that is accurately this product definition:

The Jacobi theta function is the fundamental solution of the one-dimensional heat equation with spatially periodic boundary conditions.[25] Taking z = to be real and τ = with real and positive and the nome formula , we can write down that formula:

This formula is concordant with the product formula by Whittaker and Watson.

In this case the big low leveled N shall represent Non-dimensional sizes!

This function solves the pattern of the heat equation:

This theta-function solution is 1-periodic in x, and as → 0 it approaches the periodic delta function, or Dirac comb, in the sense of distributions:

General solutions of the spatially periodic initial value problem for the heat equation may be obtained by convolving the initial data at = 0 with the theta function. The mentioned differential equation is corresponding to the Heat equation in a homogenous medium:

In this formula the letter in the expression is the Temperature at the corresponding location and time. Die mentioned up directed Delta triangle stands for the Laplace operator that is the Divergence of the Nabla Gradient operator. Furthermore t stands for the time itself, stands for the vector of the location and represents the Thermal diffusivity that is the quotient of Thermal conductivity divided by the product of Density and Specific heat capacity :

For the change in temperature in a thin and relatively long rod that is made of solid material, this heat equation is valid:

And this equation can be solved according to the above-mentioned pattern:

Relation to the Heisenberg group

The Jacobi theta function is invariant under the action of a discrete subgroup of the Heisenberg group. This invariance is presented in the article on the theta representation of the Heisenberg group.

Generalizations

If F is a quadratic form in n variables, then the theta function associated with F is

with the sum extending over the lattice of integers . This theta function is a modular form of weight n/2 (on an appropriately defined subgroup) of the modular group. In the Fourier expansion,

the numbers RF(k) are called the representation numbers of the form.

Theta series of a Dirichlet character

For χ a primitive Dirichlet character modulo q and ν = 1 − χ(−1)/2 then

is a weight 1/2 + ν modular form of level 4q2 and character

which means[26]

whenever

Ramanujan theta function

Riemann theta function

Let

be the set of symmetric square matrices whose imaginary part is positive definite. is called the Siegel upper half-space and is the multi-dimensional analog of the upper half-plane. The n-dimensional analogue of the modular group is the symplectic group Sp(2n,); for n = 1, Sp(2,) = SL(2,). The n-dimensional analogue of the congruence subgroups is played by

Then, given τ ∈ , the Riemann theta function is defined as

Here, z ∈ is an n-dimensional complex vector, and the superscript T denotes the transpose. The Jacobi theta function is then a special case, with n = 1 and τ ∈ where is the upper half-plane. One major application of the Riemann theta function is that it allows one to give explicit formulas for meromorphic functions on compact Riemann surfaces, as well as other auxiliary objects that figure prominently in their function theory, by taking τ to be the period matrix with respect to a canonical basis for its first homology group.

The Riemann theta converges absolutely and uniformly on compact subsets of .

The functional equation is

which holds for all vectors a, b ∈ , and for all z ∈ and τ ∈ .

Poincaré series

The Poincaré series generalizes the theta series to automorphic forms with respect to arbitrary Fuchsian groups.

Theta function coefficients

If a and b are positive integers, χ(n) any arithmetical function and |q| < 1, then [27]

The general case, where f(n) and χ(n) are any arithmetical functions, and f(n) : → is strictly increasing with f(0) = 0, is [27]

Derivation of the theta values

Identity of the Euler beta function

In the following, three important theta function values are to be derived as examples:

This is how the Euler beta function is defined in its reduced form:

In general, for all natural numbers this formula of the Euler beta function is valid:

Exemplary elliptic integrals

In the following some Elliptic Integral Singular Values[28] are derived:

|

The ensuing function has the following lemniscatically elliptic antiderivative: For the value this identity appears: This result follows from that equation chain: |

|

The following function has the following equianharmonic elliptic antiderivative: For the value that identity appears: This result follows from that equation chain: |

|

And the following function has the following elliptic antiderivative: For the value the following identity appears: This result follows from that equation chain: |

Combination of the integral identities with the nome

The elliptic nome function has these important values:

For the proof of the correctness of these nome values, see the article Nome (mathematics)!

On the basis of these integral identities and the above-mentioned Definition and identities to the theta functions in the same section of this article, exemplary theta zero values shall be determined now:

Partition sequences and Pochhammer products

Regular partition number sequence

The regular partition sequence itself indicates the number of ways in which a positive integer number can be splitted into positive integer summands. For the numbers to , the associated partition numbers with all associated number partitions are listed in the following table:

| n | P(n) | paying partitions |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | () empty partition/empty sum |

| 1 | 1 | (1) |

| 2 | 2 | (1+1), (2) |

| 3 | 3 | (1+1+1), (1+2), (3) |

| 4 | 5 | (1+1+1+1), (1+1+2), (2+2), (1+3), (4) |

| 5 | 7 | (1+1+1+1+1), (1+1+1+2), (1+2+2), (1+1+3), (2+3), (1+4), (5) |

The generating function of the regular partition number sequence can be represented via Pochhammer product in the following way:

The summandization of the now mentioned Pochhammer product is described by the Pentagonal number theorem in this way:

The following basic definitions apply to the pentagonal numbers and the card house numbers:

As a further application[29] one obtains a formula for the third power of the Euler product:

Strict partition number sequence

And the strict partition sequence indicates the number of ways in which such a positive integer number can be splitted into positive integer summands such that each summand appears at most once[30] and no summand value occurs repeatedly. Exactly the same sequence[31] is also generated if in the partition only odd summands are included, but these odd summands may occur more than once. Both representations for the strict partition number sequence are compared in the following table:

| n | Q(n) | Number partitions without repeated summands | Number partitions with only odd addends |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | () empty partition/empty sum | () empty partition/empty sum |

| 1 | 1 | (1) | (1) |

| 2 | 1 | (2) | (1+1) |

| 3 | 2 | (1+2), (3) | (1+1+1), (3) |

| 4 | 2 | (1+3), (4) | (1+1+1+1), (1+3) |

| 5 | 3 | (2+3), (1+4), (5) | (1+1+1+1+1), (1+1+3), (5) |

| 6 | 4 | (1+2+3), (2+4), (1+5), (6) | (1+1+1+1+1+1), (1+1+1+3), (3+3), (1+5) |

| 7 | 5 | (1+2+4), (3+4), (2+5), (1+6), (7) | (1+1+1+1+1+1+1), (1+1+1+1+3), (1+3+3), (1+1+5), (7) |

| 8 | 6 | (1+3+4), (1+2+5), (3+5), (2+6), (1+7), (8) | (1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1), (1+1+1+1+1+3), (1+1+3+3), (1+1+1+ 5), (3+5), (1+7) |

The generating function of the strict partition number sequence can be represented using Pochhammer's product:

Overpartition number sequence

The Maclaurin series[32] for the reciprocal of the function ϑ01 has the numbers of over partition sequence as coefficients with a positive sign:

If, for a given number , all partitions are set up in such a way that the summand size never increases, and all those summands that do not have a summand of the same size to the left of themselves can be marked for each partition of this type, then it will be the resulting number[33] of the marked partitions depending on by the overpartition function .

First example:

These 14 possibilities of partition markings exist for the sum 4:

| (4), (4), (3+1), (3+1), (3+1), (3+1), (2+2), (2+2), (2+1+1), (2+1+1), (2+1+1), (2+1+1), (1+1+1+1), (1+1+1+1) |

Second example:

These 24 possibilities of partition markings exist for the sum 5:

| (5), (5), (4+1), (4+1), (4+1), (4+1), (3+2), (3+2), (3+2), (3+2), (3+1+1), (3+1+1), (3+1+1), (3+1+1), (2+2+1), (2+2+1), (2+2+1), (2+2+1),

(2+1+1+1), (2+1+1+1), (2+1+1+1), (2+1+1+1), (1+1+1+1+1), (1+1+1+1+1) |

Relations of the partition number sequences to each other

In the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS), the sequence of regular partition numbers is under the code A000041, the sequence of strict partitions is under the code A000009 and the sequence of superpartitions under the code A015128. All parent partitions from index are even.

The sequence of superpartitions can be written with the regular partition sequence P[34] and the strict partition sequence Q[35] can be generated like this:

In the following table of sequences of numbers, this formula should be used as an example:

| n | P(n) | Q(n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 = 1*1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 = 1 * 1 + 1 * 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 = 2 * 1 + 1 * 1 + 1 * 1 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 = 3 * 1 + 2 * 1 + 1 * 1 + 1 * 2 |

| 4 | 5 | 2 | 14 = 5 * 1 + 3 * 1 + 2 * 1 + 1 * 2 + 1 * 2 |

| 5 | 7 | 3 | 24 = 7 * 1 + 5 * 1 + 3 * 1 + 2 * 2 + 1 * 2 + 1 * 3 |

Related to this property, the following combination of two series of sums can also be set up via the function ϑ01:

Notes

- ↑ See e.g. https://dlmf.nist.gov/20.1. Note that this is, in general, not equivalent to the usual interpretation when is outside the strip . Here, denotes the principal branch of the complex logarithm.

- ↑ for all with .

References

- ↑ Tyurin, Andrey N. (30 October 2002). "Quantization, Classical and Quantum Field Theory and Theta-Functions". arXiv:math/0210466v1.

- ↑ Chang, Der-Chen (2011). Heat Kernels for Elliptic and Sub-elliptic Operators. Birkhäuser. pp. 7.

- ↑ (in en) Tata Lectures on Theta I. Modern Birkhäuser Classics. Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston. 2007. pp. 4. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4577-9. ISBN 978-0-8176-4572-4. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-0-8176-4577-9.

- ↑ http://wayback.cecm.sfu.ca/~pborwein/TEMP_PROTECTED/pi-agm.pdf

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Toshio-Fukushima/publication/226331661_Fast_computation_of_complete_elliptic_integrals_and_Jacobian_elliptic_functions/links/0fcfd50b44bb3e76b9000000/Fast-computation-of-complete-elliptic-integrals-and-Jacobian-elliptic-functions.pdf?origin=publication_detail

- ↑ "A002103 - OEIS". https://oeis.org/A002103.

- ↑ "Series Expansion of EllipticNomeQ differs from older Mathematica Version" (in en). https://mathematica.stackexchange.com/questions/269455/series-expansion-of-ellipticnomeq-differs-from-older-mathematica-version.

- ↑ R. B. King, E. R. Canfield (1992-08-01), "Icosahedral symmetry and the quintic equation", Computers & Mathematics with Applications 24 (3): 13–28, doi:10.1016/0898-1221(92)90210-9, ISSN 0898-1221

- ↑ Adolf Kneser (1927), "Neue Untersuchung einer Reihe aus der Theorie der elliptischen Funktionen.", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 158: 209–218, ISSN 0075-4102, https://eudml.org/doc/149645, retrieved 2023-06-11

- ↑ D. K. Lee (1989-03-01), Application of theta functions for numerical evaluation of complete elliptic integrals of the first and second kinds, Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN (United States), doi:10.2172/6137964, https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6137964, retrieved 2023-06-11

- ↑ K. H. Schellbach (1864), Die Lehre von den elliptischen Integralen und den Theta-Functionen, Berlin: G. Reimer, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000617285, retrieved 2023-06-06

- ↑ Yi, Jinhee (2004). "Theta-function identities and the explicit formulas for theta-function and their applications". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 292 (2): 381–400. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2003.12.009.

- ↑ Berndt, Bruce C; Rebák, Örs (9 January 2022). "Explicit Values for Ramanujan's Theta Function ϕ(q)". Hardy-Ramanujan Journal 44: 8923. doi:10.46298/hrj.2022.8923.

- ↑ Yi, Jinhee (15 April 2004). "Theta-function identities and the explicit formulas for theta-function and their applications". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 292 (2): 381–400. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2003.12.009.

- ↑ Andreas Dieckmann: Table of Infinite Products Infinite Sums Infinite Series, Elliptic Theta. Physikalisches Institut Universität Bonn, Abruf am 1. Oktober 2021.

- ↑ Landau (1899) zitiert nach Borwein, Page 94, Exercise 3.

- ↑ "Number-theoretical, combinatorial and integer functions – mpmath 1.1.0 documentation". https://mpmath.org/doc/1.1.0/functions/numtheory.html.

- ↑ Mező, István (2013), "Duplication formulae involving Jacobi theta functions and Gosper's q-trigonometric functions", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 141 (7): 2401–2410, doi:10.1090/s0002-9939-2013-11576-5

- ↑ Mező, István (2012). "A q-Raabe formula and an integral of the fourth Jacobi theta function". Journal of Number Theory 133 (2): 692–704. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2012.08.025.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Elliptic Alpha Function". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/EllipticAlphaFunction.html.

- ↑ "integration - Curious integrals for Jacobi Theta Functions $\int_0^1 \vartheta_n(0,q)dq$" (in en). 2022-08-13. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1865615.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Jacobi Theta Functions". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/JacobiThetaFunctions.html.

- ↑ http://wayback.cecm.sfu.ca/~pborwein/TEMP_PROTECTED/pi-agm.pdf

- ↑ "DLMF: 20.5 Infinite Products and Related Results". https://dlmf.nist.gov/20.5.

- ↑ Ohyama, Yousuke (1995). "Differential relations of theta functions" (in EN). Osaka Journal of Mathematics 32 (2): 431–450. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.ojm/1200786061.

- ↑ Shimura, On modular forms of half integral weight

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Bagis, Nikos D. (26 October 2021). "q-Series Related with Higher Forms". arXiv:2006.16005 [math.GM].

- ↑ "Elliptic Integral Singular Value". https://archive.lib.msu.edu/crcmath/math/math/e/e103.htm.

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235432739_Ramanujan%27s_theta-function_identities_involving_Lambert_series [bare URL]

- ↑ "code golf - Strict partitions of a positive integer". https://codegolf.stackexchange.com/questions/71941/strict-partitions-of-a-positive-integer. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ↑ "A000009 - OEIS". 2022-03-09. https://oeis.org/A000009.

- ↑ https://www.math.lsu.edu/~mahlburg/preprints/4.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ Kim, Byungchan (28 April 2009). "Elsevier Enhanced Reader" (in en). Discrete Mathematics 309 (8): 2528–2532. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2008.05.007.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein (2022-03-11). "Partition Function P" (in en). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PartitionFunctionP.html.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein (2022-03-11). "Partition Function Q" (in en). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PartitionFunctionQ.html.

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A. (1964). Handbook of Mathematical Functions. New York: Dover Publications. sec. 16.27ff.. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0.

- Akhiezer, Naum Illyich (1990). Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions. AMS Translations of Mathematical Monographs. 79. Providence, RI: AMS. ISBN 978-0-8218-4532-5.

- Farkas, Hershel M.; Kra, Irwin (1980). Riemann Surfaces. New York: Springer-Verlag. ch. 6. ISBN 978-0-387-90465-8.. (for treatment of the Riemann theta)

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (1959). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (4th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mumford, David (1983). Tata Lectures on Theta I. Boston: Birkhauser. ISBN 978-3-7643-3109-2.

- Pierpont, James (1959). Functions of a Complex Variable. New York: Dover Publications.

- Rauch, Harry E.; Farkas, Hershel M. (1974). Theta Functions with Applications to Riemann Surfaces. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-07196-2.

- Reinhardt, William P.; Walker, Peter L. (2010), "Theta Functions", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, http://dlmf.nist.gov/20

- Whittaker, E. T.; Watson, G. N. (1927). A Course in Modern Analysis (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ch. 21. (history of Jacobi's θ functions)

Further reading

- Farkas, Hershel M. (2008). "Theta functions in complex analysis and number theory". in Alladi, Krishnaswami. Surveys in Number Theory. Developments in Mathematics. 17. Springer-Verlag. pp. 57–87. ISBN 978-0-387-78509-7.

- Schoeneberg, Bruno (1974). "IX. Theta series". Elliptic modular functions. Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. 203. Springer-Verlag. pp. 203–226. ISBN 978-3-540-06382-7.

- Ackerman, Michael (1 February 1979). "On the generating functions of certain Eisenstein series". Mathematische Annalen 244 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1007/BF01420339.

Harry Rauch with Hershel M. Farkas: Theta functions with applications to Riemann Surfaces, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore MD 1974, ISBN 0-683-07196-3.

- Charles Hermite: Sur la résolution de l'Équation du cinquiéme degré Comptes rendus, C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Nr. 11, March 1858.

External links

|