Physics:Magnetic core

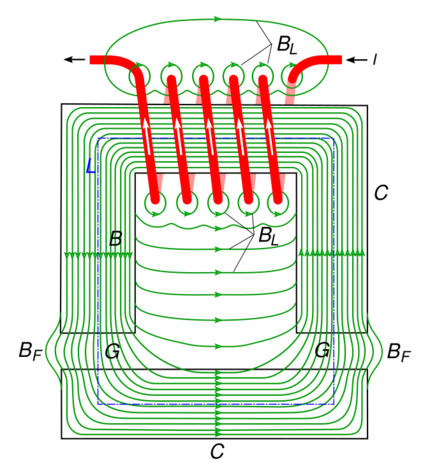

A magnetic core is a piece of magnetic material with a high magnetic permeability used to confine and guide magnetic fields in electrical, electromechanical and magnetic devices such as electromagnets, transformers, electric motors, generators, inductors, loudspeakers, magnetic recording heads, and magnetic assemblies. It is made of ferromagnetic metal such as iron, or ferrimagnetic compounds such as ferrites. The high permeability, relative to the surrounding air, causes the magnetic field lines to be concentrated in the core material. The magnetic field is often created by a current-carrying coil of wire around the core.

The use of a magnetic core can increase the strength of magnetic field in an electromagnetic coil by a factor of several hundred times what it would be without the core. However, magnetic cores have side effects which must be taken into account. In alternating current (AC) devices they cause energy losses, called core losses, due to hysteresis and eddy currents in applications such as transformers and inductors. "Soft" magnetic materials with low coercivity and hysteresis, such as silicon steel, or ferrite, are usually used in cores.

B – magnetic field in the core will be approximately constant across any cross section

BF – "fringing fields". In the gaps G the magnetic field lines "bulge" out, so the field strength is less than in the core: BF < B

BL – leakage flux; magnetic field lines which don't follow complete magnetic circuit

Core materials

An electric current through a wire wound into a coil creates a magnetic field through the center of the coil, due to Ampere's circuital law. Coils are widely used in electronic components such as electromagnets, inductors, transformers, electric motors and generators. A coil without a magnetic core is called an "air core" coil. Adding a piece of ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic material in the center of the coil can increase the magnetic field by hundreds or thousands of times; this is called a magnetic core. The field of the wire penetrates the core material, magnetizing it, so that the strong magnetic field of the core adds to the field created by the wire. The amount that the magnetic field is increased by the core depends on the magnetic permeability of the core material. Because side effects such as eddy currents and hysteresis can cause frequency-dependent energy losses, different core materials are used for coils used at different frequencies.

In some cases the losses are undesirable and with very strong fields saturation can be a problem, and an 'air core' is used. A former may still be used; a piece of material, such as plastic or a composite, that may not have any significant magnetic permeability but which simply holds the coils of wires in place.

Solid metals

Soft iron

"Soft" (annealed) iron is used in magnetic assemblies, direct current (DC) electromagnets and in some electric motors; and it can create a concentrated field that is as much as 50,000 times more intense than an air core.[1]

Iron is desirable to make magnetic cores, as it can withstand high levels of magnetic field without saturating (up to 2.16 teslas at ambient temperature.[2][3]) Annealed iron is used because, unlike "hard" iron, it has low coercivity and so does not remain magnetised when the field is removed, which is often important in applications where the magnetic field is required to be repeatedly switched.

Due to the electrical conductivity of the metal, when a solid one-piece metal core is used in alternating current (AC) applications such as transformers and inductors, the changing magnetic field induces large eddy currents circulating within it, closed loops of electric current in planes perpendicular to the field. The current flowing through the resistance of the metal heats it by Joule heating, causing significant power losses. Therefore, solid iron cores are not used in transformers or inductors, they are replaced by laminated or powdered iron cores, or nonconductive cores like ferrite.

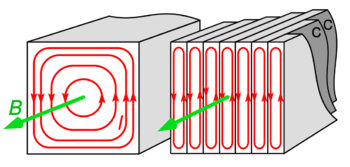

Laminated silicon steel

In order to reduce the eddy current losses mentioned above, most low frequency power transformers and inductors use laminated cores, made of stacks of thin sheets of silicon steel:

Lamination

Laminated magnetic cores are made of stacks of thin iron sheets coated with an insulating layer, lying as much as possible parallel with the lines of flux. The layers of insulation serve as a barrier to eddy currents, so eddy currents can only flow in narrow loops within the thickness of each single lamination. Since the current in an eddy current loop is proportional to the area of the loop, this prevents most of the current from flowing, reducing eddy currents to a very small level. Since power dissipated is proportional to the square of the current, breaking a large core into narrow laminations reduces the power losses drastically. From this, it can be seen that the thinner the laminations, the lower the eddy current losses.

Silicon alloying

A small addition of silicon to iron (around 3%) results in a dramatic increase of the resistivity of the metal, up to four times higher.[citation needed] The higher resistivity reduces the eddy currents, so silicon steel is used in transformer cores. Further increase in silicon concentration impairs the steel's mechanical properties, causing difficulties for rolling due to brittleness.

Among the two types of silicon steel, grain-oriented (GO) and grain non-oriented (GNO), GO is most desirable for magnetic cores. It is anisotropic, offering better magnetic properties than GNO in one direction. As the magnetic field in inductor and transformer cores is always along the same direction, it is an advantage to use grain oriented steel in the preferred orientation. Rotating machines, where the direction of the magnetic field can change, gain no benefit from grain-oriented steel.

Special alloys

A family of specialized alloys exists for magnetic core applications. Examples are mu-metal, permalloy, and supermalloy. They can be manufactured as stampings or as long ribbons for tape wound cores. Some alloys, e.g. Sendust, are manufactured as powder and sintered to shape.

Many materials require careful heat treatment to reach their magnetic properties, and lose them when subjected to mechanical or thermal abuse. For example, the permeability of mu-metal increases about 40 times after annealing in hydrogen atmosphere in a magnetic field; subsequent sharper bends disrupt its grain alignment, leading to localized loss of permeability; this can be regained by repeating the annealing step.

Vitreous metal

Amorphous metal is a variety of alloys (e.g. Metglas) that are non-crystalline or glassy. These are being used to create high-efficiency transformers. The materials can be highly responsive to magnetic fields for low hysteresis losses, and they can also have lower conductivity to reduce eddy current losses. Power utilities are currently making widespread use of these transformers for new installations.[4] High mechanical strength and corrosion resistance are also common properties of metallic glasses which are positive for this application.[5]

Powdered metals

Powder cores consist of metal grains mixed with a suitable organic or inorganic binder, and pressed to desired density. Higher density is achieved with higher pressure and lower amount of binder. Higher density cores have higher permeability, but lower resistance and therefore higher losses due to eddy currents. Finer particles allow operation at higher frequencies, as the eddy currents are mostly restricted to within the individual grains. Coating of the particles with an insulating layer, or their separation with a thin layer of a binder, lowers the eddy current losses. Presence of larger particles can degrade high-frequency performance. Permeability is influenced by the spacing between the grains, which form distributed air gap; the less gap, the higher permeability and the less-soft saturation. Due to large difference of densities, even a small amount of binder, weight-wise, can significantly increase the volume and therefore intergrain spacing.

Lower permeability materials are better suited for higher frequencies, due to balancing of core and winding losses.

The surface of the particles is often oxidized and coated with a phosphate layer, to provide them with mutual electrical insulation.

Iron

Powdered iron is the cheapest material. It has higher core loss than the more advanced alloys, but this can be compensated for by making the core bigger; it is advantageous where cost is more important than mass and size. Saturation flux of about 1 to 1.5 tesla. Relatively high hysteresis and eddy current loss, operation limited to lower frequencies (approx. below 100 kHz). Used in energy storage inductors, DC output chokes, differential mode chokes, triac regulator chokes, chokes for power factor correction, resonant inductors, and pulse and flyback transformers.[6]

The binder used is usually epoxy or other organic resin, susceptible to thermal aging. At higher temperatures, typically above 125 °C, the binder degrades and the core magnetic properties may change. With more heat-resistant binders the cores can be used up to 200 °C.[7]

Iron powder cores are most commonly available as toroids. Sometimes as E, EI, and rods or blocks, used primarily in high-power and high-current parts.

Carbonyl iron is significantly more expensive than hydrogen-reduced iron.

Carbonyl iron

Powdered cores made of carbonyl iron, a highly pure iron, have high stability of parameters across a wide range of temperatures and magnetic flux levels, with excellent Q factors between 50 kHz and 200 MHz. Carbonyl iron powders are basically constituted of micrometer-size spheres of iron coated in a thin layer of electrical insulation. This is equivalent to a microscopic laminated magnetic circuit (see silicon steel, above), hence reducing the eddy currents, particularly at very high frequencies. Carbonyl iron has lower losses than hydrogen-reduced iron, but also lower permeability.

A popular application of carbonyl iron-based magnetic cores is in high-frequency and broadband inductors and transformers, especially higher power ones.

Carbonyl iron cores are often called "RF cores".

The as-prepared particles, "E-type"and have onion-like skin, with concentric shells separated with a gap. They contain significant amount of carbon. They behave as much smaller than what their outer size would suggest. The "C-type" particles can be prepared by heating the E-type ones in hydrogen atmosphere at 400 °C for prolonged time, resulting in carbon-free powders.[8]

Hydrogen-reduced iron

Powdered cores made of hydrogen reduced iron have higher permeability but lower Q than carbonyl iron. They are used mostly for electromagnetic interference filters and low-frequency chokes, mainly in switched-mode power supplies.

Hydrogen-reduced iron cores are often called "power cores".

MPP (molypermalloy)

An alloy of about 2% molybdenum, 81% nickel, and 17% iron. Very low core loss, low hysteresis and therefore low signal distortion. Very good temperature stability. High cost. Maximum saturation flux of about 0.8 tesla. Used in high-Q filters, resonant circuits, loading coils, transformers, chokes, etc.[6]

The material was first introduced in 1940, used in loading coils to compensate capacitance in long telephone lines. It is usable up to about 200 kHz to 1 MHz, depending on vendor.[7] It is still used in above-ground telephone lines, due to its temperature stability. Underground lines, where temperature is more stable, tend to use ferrite cores due to their lower cost.[8]

High-flux (Ni-Fe)

An alloy of about 50–50% of nickel and iron. High energy storage, saturation flux density of about 1.5 tesla. Residual flux density near zero. Used in applications with high DC current bias (line noise filters, or inductors in switching regulators) or where low residual flux density is needed (e.g. pulse and flyback transformers, the high saturation is suitable for unipolar drive), especially where space is constrained. The material is usable up to about 200 kHz.[6]

Sendust, KoolMU

An alloy of 6% aluminium, 9% silicon, and 85% iron. Core losses higher than MPP. Very low magnetostriction, makes low audio noise. Loses inductance with increasing temperature, unlike the other materials; can be exploited by combining with other materials as a composite core, for temperature compensation. Saturation flux of about 1 tesla. Good temperature stability. Used in switching power supplies, pulse and flyback transformers, in-line noise filters, swing chokes, and in filters in phase-fired controllers (e.g. dimmers) where low acoustic noise is important.[6]

Absence of nickel results in easier processing of the material and its lower cost than both high-flux and MPP.

The material was invented in Japan in 1936. It is usable up to about 500 kHz to 1 MHz, depending on vendor.[7]

Nanocrystalline

A nanocrystalline alloy of a standard iron-boron-silicon alloy, with addition of smaller amounts of copper and niobium. The grain size of the powder reaches down to 10–100 nanometers. The material has very good performance at lower frequencies. It is used in chokes for inverters and in high power applications. It is available under names like e.g. Nanoperm, Vitroperm, Hitperm and Finemet.[7]

Ceramics

Ferrite

Ferrite ceramics are used for high-frequency applications. The ferrite materials can be engineered with a wide range of parameters. As ceramics, they are essentially insulators, which prevents eddy currents, although losses such as hysteresis losses can still occur.

Air

A coil not containing a magnetic core is called an air core. This includes coils wound on a plastic or ceramic form in addition to those made of stiff wire that are self-supporting and have air inside them. Air core coils generally have a much lower inductance than similarly sized ferromagnetic core coils, but are used in radio frequency circuits to prevent energy losses called core losses that occur in magnetic cores. The absence of normal core losses permits a higher Q factor, so air core coils are used in high frequency resonant circuits, such as up to a few megahertz. However, losses such as proximity effect and dielectric losses are still present. Air cores are also used when field strengths above around 2 Tesla are required as they are not subject to saturation.

Commonly used structures

Straight cylindrical rod

Most commonly made of ferrite or powdered iron, and used in radios especially for tuning an inductor. The coil is wound around the rod, or a coil form with the rod inside. Moving the rod in or out of the coil changes the flux through the coil, and can be used to adjust the inductance. Often the rod is threaded to allow adjustment with a screwdriver. In radio circuits, a blob of wax or resin is used once the inductor has been tuned to prevent the core from moving.

The presence of the high permeability core increases the inductance, but the magnetic field lines must still pass through the air from one end of the rod to the other. The air path ensures that the inductor remains linear. In this type of inductor radiation occurs at the end of the rod and electromagnetic interference may be a problem in some circumstances.

Single "I" core

Like a cylindrical rod but is square, rarely used on its own. This type of core is most likely to be found in car ignition coils.

"C" or "U" core

U and C-shaped cores are used with I or another C or U core to make a square closed core, the simplest closed core shape. Windings may be put on one or both legs of the core.

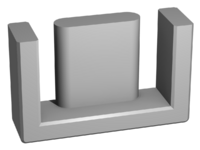

"E" core

E-shaped core are more symmetric solutions to form a closed magnetic system. Most of the time, the electric circuit is wound around the center leg, whose section area is twice that of each individual outer leg. In 3-phase transformer cores, the legs are of equal size, and all three legs are wound.

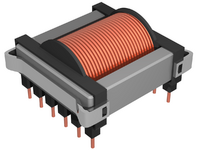

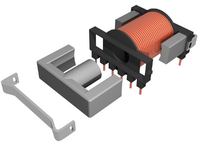

"E" and "I" core

Sheets of suitable iron stamped out in shapes like the (sans-serif) letters "E" and "I", are stacked with the "I" against the open end of the "E" to form a 3-legged structure. Coils can be wound around any leg, but usually the center leg is used. This type of core is frequently used for power transformers, autotransformers, and inductors.

Pair of "E" cores

Again used for iron cores. Similar to using an "E" and "I" together, a pair of "E" cores will accommodate a larger coil former and can produce a larger inductor or transformer. If an air gap is required, the centre leg of the "E" is shortened so that the air gap sits in the middle of the coil to minimize fringing and reduce electromagnetic interference.

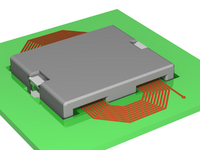

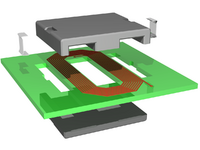

Planar core

A planar core consists of two flat pieces of magnetic material, one above and one below the coil. It is typically used with a flat coil that is part of a printed circuit board. This design is excellent for mass production and allows a high power, small volume transformer to be constructed for low cost. It is not as ideal as either a pot core or toroidal core[citation needed] but costs less to produce.

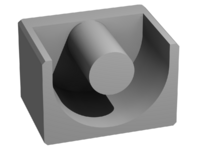

Pot core

Usually ferrite or similar. This is used for inductors and transformers. The shape of a pot core is round with an internal hollow that almost completely encloses the coil. Usually a pot core is made in two halves which fit together around a coil former (bobbin). This design of core has a shielding effect, preventing radiation and reducing electromagnetic interference.

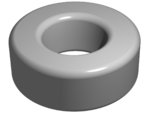

Toroidal core

This design is based on a toroid (the same shape as a doughnut). The coil is wound through the hole in the torus and around the outside. An ideal coil is distributed evenly all around the circumference of the torus. The symmetry of this geometry creates a magnetic field of circular loops inside the core, and the lack of sharp bends will constrain virtually all of the field to the core material. This not only makes a highly efficient transformer, but also reduces the electromagnetic interference radiated by the coil.

It is popular for applications where the desirable features are: high specific power per mass and volume, low mains hum, and minimal electromagnetic interference. One such application is the power supply for a hi-fi audio amplifier. The main drawback that limits their use for general purpose applications is the inherent difficulty of winding wire through the center of a torus.

Unlike a split core (a core made of two elements, like a pair of E cores), specialized machinery is required for automated winding of a toroidal core. Toroids have less audible noise, such as mains hum, because the magnetic forces do not exert bending moment on the core. The core is only in compression or tension, and the circular shape is more stable mechanically.

Ring or bead

The ring is essentially identical in shape and performance to the toroid, except that inductors commonly pass only through the center of the core, without wrapping around the core multiple times.

The ring core may also be composed of two separate C-shaped hemispheres secured together within a plastic shell, permitting it to be placed on finished cables with large connectors already installed, that would prevent threading the cable through the small inner diameter of a solid ring.

AL value

The AL value of a core configuration is frequently specified by manufacturers. The relationship between inductance and AL number in the linear portion of the magnetisation curve is defined to be:

where n is the number of turns, L is the inductance (e.g. in nH) and AL is expressed in inductance per turn squared (e.g. in nH/n2).[9]

Core loss

When the core is subjected to a changing magnetic field, as it is in devices that use AC current such as transformers, inductors, and AC motors and alternators, some of the power that would ideally be transferred through the device is lost in the core, dissipated as heat and sometimes noise. Core loss is commonly termed iron loss in contradistinction to copper loss, the loss in the windings.[10][11] Iron losses are often described as being in three categories:

Hysteresis losses

When the magnetic field through the core changes, the magnetization of the core material changes by expansion and contraction of the tiny magnetic domains it is composed of, due to movement of the domain walls. This process causes losses, because the domain walls get "snagged" on defects in the crystal structure and then "snap" past them, dissipating energy as heat. This is called hysteresis loss. It can be seen in the graph of the B field versus the H field for the material, which has the form of a closed loop. The net energy that flows into the inductor expressed in relationship to the B-H characteristic of the core is shown by the equation[12]

This equation shows that the amount of energy lost in the material in one cycle of the applied field is proportional to the area inside the hysteresis loop. Since the energy lost in each cycle is constant, hysteresis power losses increase proportionally with frequency.[13] The final equation for the hysteresis power loss is[12]

Eddy-current losses

If the core is electrically conductive, the changing magnetic field induces circulating loops of current in it, called eddy currents, due to electromagnetic induction.[14] The loops flow perpendicular to the magnetic field axis. The energy of the currents is dissipated as heat in the resistance of the core material. The power loss is proportional to the area of the loops and inversely proportional to the resistivity of the core material. Eddy current losses can be reduced by making the core out of thin laminations which have an insulating coating, or alternatively, making the core of a magnetic material with high electrical resistance, like ferrite.[15] Most magnetic cores intended for power converter application use ferrite cores for this reason.

Anomalous losses

By definition, this category includes any losses in addition to eddy-current and hysteresis losses. This can also be described as broadening of the hysteresis loop with frequency. Physical mechanisms for anomalous loss include localized eddy-current effects near moving domain walls.

Legg's equation

An equation known as Legg's equation models the magnetic material core loss at low flux densities. The equation has three loss components: hysteresis, residual, and eddy current,[16][17][18] and it is given by

where

- is the effective core loss resistance (ohms),

- is the material permeability,

- is the inductance (henrys),

- is the hysteresis loss coefficient,

- is the maximum flux density (gauss),

- is the residual loss coefficient,

- is the frequency (hertz), and

- is the eddy loss coefficient.

Steinmetz coefficients

Losses in magnetic materials can be characterized by the Steinmetz coefficients, which however do not take into account temperature variability. Material manufacturers provide data on core losses in tabular and graphical form for practical conditions of use.

See also

References

- ↑ "Soft iron core". http://www.physicsforums.com/archive/index.php/t-164613.html.

- ↑ Daniel Sadarnac, Les composants magnétiques de l'électronique de puissance, cours de Supélec, mars 2001 [in french]

- ↑ Danan, H.; Herr, A.; Meyer, A.J.P. (1968-02-01). "New Determinations of the Saturation Magnetization of Nickel and Iron". Journal of Applied Physics 39 (2): 669–70. doi:10.1063/1.2163571. ISSN 0021-8979. Bibcode: 1968JAP....39..669D.

- ↑ "Metglas® Amorphous Metal Materials – Distribution Transformers". https://www.hitachimetals.com/infrastructure-energy/clean-energy-technology/metglas-amorphous-metal-materials-distribution-transformers.php.

- ↑ Inoue, A.; Kong, F. L.; Han, Y.; Zhu, S. L.; Churyumov, A.; Shalaan, E.; Al-Marzouki, F. (2018-01-15). "Development and application of Fe-based soft magnetic bulk metallic glassy inductors" (in en). Journal of Alloys and Compounds 731: 1303–1309. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.08.240. ISSN 0925-8388. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092583881732978X.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 others, The Zen Cart™ Team and. "How to choose Iron Powder, Sendust, Koolmu, High Flux and MPP Cores as output inductor and chokes : CWS Coil Winding Specialist, manufacturer of transformers, inductors, coils and chokes". http://www.coilws.com/index.php?main_page=page&id=41.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Johan Kindmark, Fredrik Rosén (2013). "Powder Material for Inductor Cores, Evaluation of MPP, Sendust and High flux core characteristics". Göteborg, Sweden: Department of Energy and Environment, Division of Electric Power Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology. http://publications.lib.chalmers.se/records/fulltext/183920/183920.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Goldman, Alex (6 December 2012). Handbook of Modern Ferromagnetic Materials. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781461549178. https://books.google.com/books?id=StbgBwAAQBAJ&dq=powder+core+%22carbonyl+iron%22&pg=PA185.

- ↑ http://www.jmag-international.com/catalog/101_ChokeCoil_CurrentCharacteristic.html, AL Value

- ↑ Thyagarajan, T.; Sendur Chelvi, K.P.; Rangaswamy, T.R. (2007). Engineering Basics: Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (3rd ed.). New Age International. pp. 184–185. ISBN 9788122412741. https://books.google.com/books?id=oY-pcBq0z48C&pg=PA185.

- ↑ Whitfield, John Frederic (1995). Electrical Craft Principles. 2 (4th ed.). IET. p. 195. ISBN 9780852968338. https://books.google.com/books?id=b31Z2x1ZlUEC&pg=PA195.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Erickson, Robert; Maksimović, Dragan (2001). Fundamentals of Power Electronics, Second Edition. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 506. ISBN 9780792372707.

- ↑ Dhogal, P.S. (1986). Basic Electrical Engineering, Volume 1. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 128. ISBN 9780074515860.

- ↑ Kazimierczuk, Marian K. (2014). High-frequency magnetic components (Second ed.). Chichester: Wiley. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-118-71779-0.

- ↑ Erickson, Robert; Maksimović, Dragan (2001). Fundamentals of Power Electronics, Second Edition. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 507. ISBN 9780792372707.

- ↑ Arnold Engineering Company n.d., p. 70

- ↑ Legg, Victor E. (January 1936), "Magnetic Measurements at Low Flux Densities Using the Alternating Current Bridge", Bell System Technical Journal (Bell Telephone Laboratories) 15 (1): 39–63, doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1936.tb00718.x, http://www3.alcatel-lucent.com/bstj/vol15-1936/articles/bstj15-1-39.pdf

- ↑ Snelling, E.C. (1988). Soft ferrites : properties and applications (2nd ed.). London: Butterworths. ISBN 978-0408027601. OCLC 17875867.

- Arnold Engineering Company (n.d.), MPP Cores, Marengo, IL: Arnold Engineering Company

External links

- Online calculator for ferrite coil winding calculations

- What are the bumps at the end of computer cables?

- How to use ferrites for EMI suppression via Wayback Machine by Murata Manufacturing

|