Engineering:D'Estrées-class cruiser

Infernet

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Destrées |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | missing name |

| Succeeded by: | missing name |

| In commission: | 1899–1922 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Lost: | 1 |

| Retired: | 1 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 2,428 long tons (2,467 t) |

| Length: | 95 m (311 ft 8 in) loa |

| Beam: | 12 m (39 ft 4 in) |

| Draft: | 5.39 m (17 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph) |

| Range: | 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 235 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | Deck: 38 to 43 mm (1.5 to 1.7 in) |

The D'Estrées class comprised two protected cruisers of the French Navy built in the late 1890s. The two ships were missing name and missing name, though a third was projected but was canceled before work began. They were ordered during a period of intense debate in the French fleet between officers who favored large armored cruisers and those who preferred smaller vessels more suited to long-distance cruising abroad. The D'Estrées-class cruisers were intended to operate in the French colonial empire. The ships were armed with a main battery of two 138 mm (5.4 in) guns supported by four 100 mm (3.9 in) guns and they had a top speed of 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph).

D'Estrées and Infernet initially served in the Northern Squadron after entering service in the late 1890s, though they were quickly transferred elsewhere. D'Estrées went to the Atlantic station in 1902, while Infernet had been sent to French Madagascar by 1901. The latter ship then served a stint in the East Indies from 1903 to 1905, thereafter returning to France, where she was lost in an accidental grounding in 1910. D'Estrées was assigned to the 2nd Light Division at the start of World War I in August 1914 before being moved to the Syrian Division, where she took part in operations against Ottoman forces ashore. She patrolled the Red Sea and Indian Ocean from 1916 to the end of the war in 1918. D'Estrées was then sent to East Asia, where she served until being discarded in 1922.

Design

In the 1880s and 1890s, factions in the French Navy's officer corps argued over the types of cruiser that best served France's interests. Some argued for a fleet of small but fast protected cruisers for commerce raiding, another sought larger and more powerful armored cruisers that were useful for patrolling the country's colonial possessions, while another preferred vessels more suited to operations with the home fleet of battleships. In 1896, the Conseil supérieur de la Marine (Superior Naval Council) ordered the two cruisers of the D'Estrées class for the construction program that was to begin that year at the behest of the colonialists for use in the French overseas empire.[1] A third member of the class, provisionally designated "K3", was authorized in 1897 but was not built; by that time, the French naval command had decided to build larger armored cruisers for all cruiser tasks, including colonial patrol duties.[2]

Characteristics and machinery

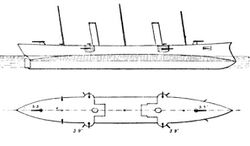

The two ships of the D'Estrées class were 95 m (311 ft 8 in) long overall, with a beam of 12 m (39 ft 4 in) and a draft of 5.39 m (17 ft 8 in). They displaced 2,428 long tons (2,467 t). Their crew numbered 235 officers and enlisted men.[3]

The ships' hulls included a ram bow and an overhanging stern, but unlike other French cruisers of the period, they lacked a double bottom or a longitudinal bulkhead. Below the waterline, they were covered with a layer of wood and copper sheathing to protect them from biofouling on extended voyages overseas, where they would not have reliable access to shipyard facilities. The ships had a flush deck and a minimal superstructure, consisting primarily of a small conning tower. They had three pole masts, though one was later removed from each vessel.[3]

The ships' propulsion system consisted of a pair of vertical triple-expansion steam engines driving two screw propellers. Each engine was placed in its own engine room, divided by a watertight bulkhead to prevent flooding from disabling both engines. Steam was provided by eight coal-burning Normand-type water-tube boilers that were ducted into two widely-spaced funnels. The boilers were divided into pairs in four boiler rooms.[3][4]

Their machinery was rated to produce 8,500 indicated horsepower (6,300 kW) for a top speed of 20 to 20.5 knots (37.0 to 38.0 km/h; 23.0 to 23.6 mph). They carried 340 long tons (345 t) of coal for the boilers, and up to 470 long tons (480 t) at full load,[5][3] which gave the ships a cruising radius of up to 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), according to the contemporary Journal of the Royal United Service Institution.[6] Warship International, citing the 1905 Marine Almanac, credits the class with a cruising radius of just 4,500 nmi (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) at 10 knots.[5]

Armament and armor

The ships were armed with a main battery of two 138 mm (5.4 in) Modèle 1893 45-caliber guns. They were placed in individual pivot mounts with gun shields, one forward and aft on the centerline.[3] They were supplied with a variety of shells, including solid, 30 kg (66 lb) cast iron projectiles, and 35 kg (77 lb) explosive armor-piercing (AP) and semi-armor-piercing (SAP) shells, firing with a muzzle velocity of 730 to 770 m/s (2,400 to 2,500 ft/s).[7]

The main battery was supported by a secondary battery of four 100 mm (3.9 in) Modèle 1891 guns, which were carried in sponsons in the hull. One pair was placed abreast the conning tower, and the other set of guns was located on either side of the rear funnel.[3] The guns fired 14 kg (31 lb) cast iron and 16 kg (35 lb) AP shells with a muzzle velocity of 710 to 740 m/s (2,300 to 2,400 ft/s).[8]

For close-range defense against torpedo boats, the vessels carried eight 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and two 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder guns. These were mounted in individual pivot mountings that were distributed along the length of the ship, some atop the upper deck and others firing through gun ports in the upper deck.[3] The ships were also equipped with fourteen naval mines.[9]

Armor protection consisted of a curved armor deck that was 38 to 43 mm (1.5 to 1.7 in) thick in the central portion of the ships, where it protected the propulsion machinery spaces and the ammunition magazines. The deck was reduced in thickness toward the bow and stern, falling to 20 mm (0.79 in). Above the deck at the sides, a cofferdam filled with cellulose was intended to contain flooding from damage below the waterline.[3]

Construction

| Name | Laid down[3] | Launched[10] | Completed[3] | Shipyard[3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| missing name | March 1897 | 27 October 1897 | 1899 | Arsenal de Rochefort, Rochefort |

| missing name | December 1896 | 7 September 1899 | 1900 | Forges et Chantiers de la Gironde, Lormont |

| K3[5] | — | — | — | — |

Service history

D'Estrées served in the Northern Squadron after her completion in 1899,[11] where she was joined by Infernet by early 1901.[12] The latter vessel was transferred to French Madagascar later in 1901,[13] and in 1902, D'Estrées was reassigned to the Atlantic Training Division.[14] She remained there for the next several years, though the unit went through a series of name changes and reorganizations.[15][16] Infernet was moved again in 1903, this time to the East Indies to protect French interests in the region. She returned to France in 1905. In 1908, D'Estrées was sent to patrol the West Indies, and by that time, the Atlantic Division had been merged into the Northern Squadron.[17][18] Infernet's career was cut short in 1910, when she ran aground off Les Sables-d'Olonne in 1910 and could not be pulled free.[19][20][10]

At the start of World War I in August 1914, D'Estrées was initially assigned to the 2nd Light Squadron, which was based in the English Channel, but was quickly transferred to reinforce the Syrian Division for operations against the Ottoman Empire.[21][22] D'Estrées bombarded Ottoman positions along the Syrian coast and helped to enforce a blockade there. She also assisted in the evacuation of some 4,000 Armenians from Antakya on 12 and 13 September, along with several other French cruisers.[23][24] She was moved to the Red Sea in 1916, where she patrolled for the German commerce raider Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist., which was known to be operating in the Indian Ocean. She remained in the region for the rest of the war, though she saw no further action.[25][26][27] After the war, she was sent to French Indochina, where she spent the remainder of her career. D'Estrées was struck from the naval register in 1922 and broken up.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Ropp, pp. 284, 286.

- ↑ Fisher, pp. 238–239.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Campbell, p. 313.

- ↑ Ships, pp. 1007–1008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Fisher, p. 239.

- ↑ Garbett 1904, p. 563.

- ↑ Friedman, p. 224.

- ↑ Friedman, p. 225.

- ↑ Ships, p. 1008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Smigielski, p. 193.

- ↑ Leyland 1900, p. 64.

- ↑ Jordan & Caresse 2017, p. 218.

- ↑ Leyland 1901, p. 76.

- ↑ Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 74.

- ↑ Brassey 1903, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Garbett 1903, p. 944.

- ↑ Brassey 1908, pp. 49, 51–52.

- ↑ Garbett 1908, p. 100.

- ↑ "Maritime Intelligence". Shipping & Mercantile Gazette, and Lloyd's List: p. 8. 18 November 1910. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001941/19101118/159/0008.

- ↑ "Maritime Intelligence". Shipping & Mercantile Gazette, and Lloyd's List: p. 11. 22 November 1910. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0001941/19101122/146/0011.

- ↑ Meirat, p. 22.

- ↑ Corbett, p. 369.

- ↑ Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 235.

- ↑ Reynolds, Churchill, & Trevelyan, p. 505.

- ↑ Jordan & Caresse 2019, pp. 235–236, 240, 247.

- ↑ Smigielski, p. 194.

- ↑ Guilliatt & Hohnen, p. 192.

References

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1903). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.): 57–68. OCLC 496786828. https://books.google.com/books?id=9pBIAQAAMAAJ.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1908). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.): 48–57. OCLC 496786828. https://books.google.com/books?id=rJBIAQAAMAAJ.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "France". in Gardiner, Robert. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 283–333. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5. https://archive.org/details/conwaysallworlds0000unse_l2e2.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1921). Naval Operations: From the Battle of the Falklands to the Entry of Italy Into the War in May 1915. II. London: Longmans, Green & Co.. OCLC 924170059.

- Fisher, Edward C., ed (1969). "157/67 French Protected Cruiser Isly". Warship International (Toledo: International Naval Research Organization) VI (3): 238. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed (August 1903). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution (London: J. J. Keliher & Co.) XLVII (306): 941–946. OCLC 1077860366. https://books.google.com/books?id=bCkmAQAAIAAJ&dq=cruiser+Jurien&pg=PA944.

- Garbett, H., ed (May 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution (London: J. J. Keliher & Co.) XLVIII (315): 560–566. OCLC 1077860366.

- Garbett, H., ed (January 1908). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution (London: J. J. Keliher & Co.) LLI (359): 100–103. OCLC 1077860366. https://books.google.com/books?id=wRhjCSPB348C.

- Guilliatt, Richard; Hohnen, Peter (2010). The Wolf: How One German Raider Terrorized the Allies in the Most Epic Voyage of WWI. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-1416573173.

- Jordan, John; Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Jordan, John; Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- Leyland, John (1900). Brassey, Thomas A.. ed. "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.): 63–70. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John (1901). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.): 33–70. OCLC 496786828. https://books.google.com/books?id=EJFIAQAAMAAJ.

- Meirat, Jean (1975). "Details and Operational History of the Third-Class Cruiser Lavoisier". F. P. D. S. Newsletter (Akron: F. P. D. S.) III (3): 20–23. OCLC 41554533.

- The Story of the Great War: History of the European War from Official Sources. III. New York: P.F. Collier & Son. 1916. OCLC 633621894.

- Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-5267-4533-0.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S.. ed. The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- "Ships". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers (Washington D.C.: R. Beresford) XI (4): 1081–1116. November 1899.

- Smigielski, Adam (1985). "France". in Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 190–220. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8. https://archive.org/details/conwaysallworlds0000unse_z3o0.

|