Engineering:Mount Polley tailings spill

24 July 2014  5 August 2014 USGS satellite photos of the Mount Polley Mine site before and after the dam breach | |

| Date | 4 August 2014 |

|---|---|

| Location | Quesnel Lake, British Columbia, Canada |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 52°30′48″N 121°35′47″W / 52.513437°N 121.596309°W |

| Cause | Failure of tailings pond dam |

| Footage | Footage: Youtube |

| [1] | |

The Mount Polley tailings spill occurred in the Cariboo region of central British Columbia, Canada . The spill began 4 August 2014 with a breach of the Imperial Metals-owned Mount Polley copper, gold and silver mine tailings pond, releasing its water and slurry with years worth of mining waste into Polley Lake. The spill flooded Polley Lake, creating a plug at Hazeltine Creek, and continued into nearby Quesnel Lake and Cariboo River. By 8 August the four-square-kilometre (1.5 sq mi) sized tailings pond had been emptied of the majority of supernatant (process water) that sits atop the settled crushed rock solids (mining waste, or 'tailings'). The cause of the dam breach and subsequent tailings spill has been investigated with a final report published 31 January 2015. Imperial Metals had a history of operating the pond beyond capacity since at least 2011. Remediation and reconstruction has been underway at the site since 2014. These efforts have included investigation on impacts to human health and safety and affected ecosystems while removing the tailings spill, reconstructing creek shorelines, installing fish habitats, and replanting trees and other local vegetation. Investigation by the remediation team showed elevated levels of selenium, arsenic and other metals consistent with historical tests before the dam breach. These initial reports had been concerned about the chemical impact of the tailings spill on the surrounding environment, but it was determined through subsequent investigation and remediation that the challenge posed by tailings spill was physical in nature.

Breach and spill

Composition of tailings pond

Tailings are the remainder of what remains after desired minerals have been removed. The Mount Polley Mining Corporation mined copper, gold, and silver from their mine at Mount Polley. The volcanic rock from which the desired minerals are extracted contains a mixture of orthoclase (36.95%), albite (24.38%), magnetite (7.38%), calcium plagioclase(7.12%), diopside (4.48%), garnet (3.33%), biotite (3.04%), epidote (2.12%), calcite (2.01%), chalcopyrite (0.17%), and pyrite (0.04%).[2] The tailings at Mount Polley contain a usually low amount of chalcopyrite and a high amount of calcite, making them geochemically benign. A typical concern of the tailings of metal mining such as acid rock drainage does not occur at Mount Polley due to the unique distribution of compounds in the volcanic rock. The relatively high levels of calcite allow the mineral to act as a neutralizing agent for sulphides that are constituent in the chalcopyrite and pyrite.[3] Therefore, the crushed rock tailings of Mount Polley are virtually inert, not reactive with air or water, instead having properties like natural sand.

Dam breach

The Mount Polley open pit copper and gold tailings spill in the Cariboo region of British Columbia began in the early morning of 4 August 2014 with a partial breach of the tailings pond dam, releasing 10 million cubic metres (10 billion litres; 2.6 billion US gallons) of water and 4.5 million cubic metres (4.5 billion litres; 1.2 billion US gallons)[4] of slurry into Polley Lake.[5] Another source gives the quantity spilled as: 7.3 million cubic metres (7.3 billion litres; 1.9 billion US gallons) of tailings, 10.6 million cubic metres (10.6 billion litres; 2.8 billion US gallons) of water, and 6.5 million cubic metres (6.5 billion litres; 1.7 billion US gallons) of interstitial water.[6] The slurry of tailings and process water carried felled trees, mud and debris and "scoured away the banks" of Hazeltine Creek which flows out of Polley Lake and continued into the nearby Quesnel Lake. The spill caused Polley Lake to rise by 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[7] Hazeltine Creek was transformed from a two-metre-wide (6.6 ft) stream to a 50-metre-across (160 ft) "wasteland"*[8] and Cariboo Creek was also affected.[4] As of 8 August 2014, the tailings continued to pour into Quesnel Lake. By the end of the day the four-square-kilometre (1.5 sq mi) sized tailings pond was "virtually empty".[4][7] Mine safety experts and media articles have called the spill one of the biggest environmental disasters in modern Canadian history.[9][10] British Columbia's government initially insisted the dam failure was not an environmental disaster but stated "We will have a much better idea 24 hours from now on the quality in Quesnel Lake," ,[11] a position clarified again by British Columbia's Environment Minister, Mary Polak, in November 2014 after more sampling data became available.[12] On August 6, two days after the breach, the British Columbia Ministry of Environment issued a Pollution Abatement Order to Mount Polley Mining Corporation. The company submitted an action plan for the Preliminary Environmental Impact Assessment, environmental monitoring, stopping the flow from the "Tailings Impoundment" breach, as required. The company was required and did report weekly on the implementation of action plan measures.[4]

State of local emergency

On 6 August 2014 Cariboo Regional District declared a local state of emergency in several nearby communities, including Likely, British Columbia, partly because of concerns over the quality of drinking water, which affected 300 residents.[7] On August 9, water use restrictions were removed for residents of Likely and downstream from that community based on water quality testing by the British Columbia Government. However, the government continued the advisory for points upstream of Likely. On August 12, Interior Health further rescinded the ban on drinking water, narrowing the "Do Not Use" order to only the impact zone directly affected by the breach, which includes Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek, and an area within 100 metres (330 ft) of the shoreline sediment deposit, where Hazeltine Creek runs into Quesnel Lake. This remaining advisory is expected to stay in place indefinitely. The government advised that boiling the water would not help in the "do not use" areas.[4][13][14] All five testing sites of the second water test run had zinc levels above chronic, or long-term, exposure limits for aquatic life.[13]

The government described the purpose of the state of local emergency was to provide "exceptional" powers in the interest of public safety, and an equitable distribution of potable water to the residents of Likely. All tourism businesses in the affected areas remained open. Because the affected water system is salmon-bearing, there was a temporary closure of part of the Chinook salmon fishery by Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Fishing along the Fraser River was not affected. Rainbow trout toxicity test results from water collected at Quesnel Lake near the mouth of Hazeltine Creek on August 5 and 6 showed water was not toxic to rainbow trout.[4][14]

Political Reaction

The University of Victoria Environmental Law Centre filed a complaint with B.C.’s privacy commissioner regarding the government not releasing environmental assessments and dam inspection reports about Mount Polley mine; after journalists found a dam inspection report from 2010 and environmental assessments from 1992 and 1997 in public libraries,[15] the B.C. government has withheld subsequent reports.[12] Indigenous political activists led by Kanahus Manuel set up blockades and held numerous community based protests against Imperial Metals following the disaster.[16]

Since the spill, Alaskan mine opponents, including environmentalists such as Trout Unlimited Alaska, aboriginal peoples, the fishing industry and politicians, point to several planned B.C. mining projects involving three major salmon-producing river systems that run downstream into Southeast Alaska. The large Red Chris gold and copper mine owned by Newcrest Mining is now in operation and located in the headwaters of the Iskut River, a major tributary of the Stikine River whose estuary is near Petersburg and Wrangell, Alaska.[12] The KSM project owned by Seabridge Gold Inc has been approved by B.C., awaits federal approval and is located near the Unuk River system supporting one of Southeast Alaska's largest Chinook salmon population, and flows into Alaska, although its tailings facility would be located in the Nass River watershed emptying into the Pacific in B.C. A third mine is slated to reopen and expand in the Taku River near Juneau.[17]

Remediation

Investigation of root cause

On 18 August 2014, the British Columbia government, with support of the Soda Creek Indian Band and Williams Lake Indian Band, ordered an independent engineering investigation into the pond breach and a third-party review of all 2014 dam safety inspections for every permitted mine's tailings pond in the province. The panel reviewing this breach was composed of Norbert Morgenstern, P.Eng., Dirk van Zyl, P.Eng., and Steven Vick. Their final report was published 31 January 2015.[18] The investigation covered many factors, including the question of whether the piezometers measuring the water pressure on the dam had been located correctly. The last readings, 2 August 2014, did not show any changes in the water pressure.[4] A principal finding of the panel determined that the tailings dam collapsed because of its construction on underlying earth containing a layer of glacial till, which had been unaccounted for by the company's original engineering contractor.[19] In 2010, Mount Polley Mining Corporation's (MPMC) engineering firm reported a 10-metre (33 ft) crack in the earthen dam while working to raise it, and that piezometers were broken, which were later fixed.[20] In 2018, the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of British Columbia charged three engineers who worked on the tailings storage facility with negligence or unprofessional conduct.[21]

Water management

The long-term water management plan for the Mount Polley mine site has been approved by an independent statutory-decision maker from the Ministry of Environment and is expected to be fully in place by fall 2017 and will replace the short-term water management plan that has been in place since 30 November 2015.

Mount Polley Mining Corporation submitted its formal permit amendment application, which included the long-term water management plan and supporting Technical Assessment Report, in October 2016. The documents were subject to extensive public consultation, including First Nations and local communities. The application also underwent a full technical review from the Cariboo Mine Development Review Committee (CMDRC), which includes representatives from provincial and federal agencies, First Nations, local governments (City of Williams Lake and Cariboo Regional District), and the community of Likely.

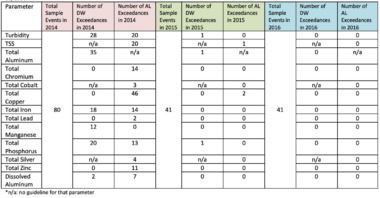

Tailings treatment

The Mount Polley Mining Corporation (MPMC) treats mine site water with water treatment plant technology by Veolia prior to release into Quesnel lake. The water is monitored for turbidity at 15 second intervals and water quality is assessed at Quesnel lake as part of MPMC's Comprehensive Environmental Monitoring Plan.[22] About 15,000 cubic meters of site water is discharged into Quesnel lake per day. This is below the 29,000 cubic meters threshold allowed under the mining corporation's permit.[23]. The water at Quesnel lake, Quesnel river, Polley lake, and Hazeltine creek are regularly monitored by the Ministry of Environment.[24][25][26][27][28]

Remediation timeline

The Mount Polley Mining Corporation has invested more than $70 million into remediation efforts since the dam breach in 2014.[29] No government funding has been spent on the clean-up or repair work at the site. The restoration and remediation strategy was carried out in four stages: impact reduction, post-breach environmental assessment, long-term health and environmental assessment, and implementation of work focused on remediation to prevent environmental and health impacts and to improve the condition of the areas affected by breach.

2014

In August, MPMC submitted an interim erosion plan and a sediment control plan to mitigate ongoing erosion and sediment transport downstream, to control further flow from the tailings area, and to improve the quality of water flowing into Quesnel Lake.[18] In the beginning of September 2014, a berm to prevent further spread of tailings was nearing completion and laid off workers, about 40 of the mine's approximately 300 workers demanded to reopen the mine. a spokesman at the Ministry of Mine said operations would require permits and approvals and could only go ahead after a rigorous review.[30] The primary phase of the restoration and remediation strategy implemented work to reduce the environmental effect on Quesnel Lake.

2015

In June 2015, the Post-Event Environmental Impact Assessments Report was published as part of the second phase of the strategy.[31] The report was submitted by Golder Associates to the Mount Polley Mining Corporation to determine the physical, biological, and chemical implications 6–8 months after the dam breach. The report detailed steps taken by the MPMC to stabilize the tailings storage facility by creating two rock berms inside the facility, to provide safe access to Hazeltine creek by reducing the elevation of Polley Lake behind the point of the blockage caused by the discharge of tailings effluent, and to stop inputs from the tailings storage facility. Specialists and environmental scientists and engineers were hired to study the impact of the spill from the tailings dam. This team studied where tailings effluent was deposited on land and in surrounding water environments, in particular how the bottom of Quesnel Lake was affected and how the structures of Hazeltine and Edney creeks had changed. Chemical studies studied soil, water and sediment changes, while biological studies were focused on the effect of aquatic plant and animal life, in particular those at the sediment layer. Biological assessment also studied soil-dependent biota in the areas surrounding Quesnel Lake and Polley Lake.

The Assessments Report determined nine areas requiring ongoing monitoring to determine localized strategies for remediation efforts in each location.[31] These areas included the tailings storage facility, the Polley plug (a blockage area between the tailings effluent and Polley Lake), Polley Lake, upper Hazeltine creek, Hazeltine Canyon, lower Hazeltine creek, the mouth of Edney creek, Quesnel Lake, and Quesnel River.

The report concluded that Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek and a small portion of Quesnel Lake were physically affected by the tailings dam breach.[31] The chemical testing on the tailings mixture was determined to be relatively inert though it was found that a higher concentration of copper was contained in the effluent compared to before the breach. Biological testing found copper contained within lake sediment and within the water was not toxic to aquatic life. Soil testing of copper levels determined a level higher than provincial standards for the protection of invertebrates and plants but at far lower levels than the provincial standards for the protection of human health. Deep water analysis found copper to be at levels below the Provincial Water Quality Guideline. Despite the levels of copper present due to presence in the tailings, the report determined it was unlikely to be released from the tailings and therefore adverse effects were deemed unlikely.

The restoration of the shoreline of Hazeltine creek began to create a stable water flow and to begin the restoration of fish and associated wildlife habitats. This was preceded by floodplain grading and the determination of the physical land characterists of the areas surrounding the shoreline. A flow study to determine an ideal range and the annual mean for natural habitats was completed before construction of rock weirs and habitat features. Planting on the floodplain, to continue over subsequent years had also begun.[31] Repairs to the mouth of lower Edney Creek was completed connecting the waterway to Quesnel Lake. By the spring of 2015, remediation work had installed a new fish habitat at lower Edney Creek. Successful spawning of interior Coho, Kokanee and Sockeye Salmon was accomplished. By May, a new channel for Hazeltine Creek was completed.

On 13 July 2015, Interior Health, the regional public health authority, declared all water restrictions lifted and determined water sourced from Polley Lake and Hazeltine Creek safe for consumption and recreation from a health perspective. A review of the water, sediment and fish toxicology samples from the Ministry of the Environment determined no known risks to human health.[32]

2016

A detailed site investigation was completed by Golder Associates in January 2016 as mandated by the Pollution Abatement Order issued by the British Columbia Ministry of Environment. This work was part of investigation and remediation work ongoing at the Mount Polley site. The detailed site investigation was completed to produce a Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) report and an Ecological Risk Assessment for the affected site.

The Post-Event Environmental Impact Assessment Report update was completed in June 2015 by Golder Assocaties.

Remediation work was conducted in tandem with investigative work done by Golder.

The Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) was completed by Golder Associates as part of that company's work toward implementing the Mount Polley remediation strategy.[33] The produced report detailed current recreational and commercial uses of Polley Lake, Quesnel Lake, and Quesnel River and their environs including fisheries, swimming, boating, kayaking, canoeing, waterskiing, snowmobiling, and ice fishing. The report also noted the use of Quesnel Lake as a source of drinking water for nearby residences. As such the report investigated effect of the dam breach on human health, in particular subsistence land users, Quesnel Lake residents, and recreational land users.

The HHRA report found that soil, surface water, and the air did not contain contaminants of particular concern that were present or that exceeded contaminated site regulations. The sediment layer exceeded the regulatory standard for lead, while vegetation had copper and vanadium present, and aluminum, copper, and vanadium were present in the fish.[33]

The HHRA report concluded that the risks were low to subsistence land users, recreational land users, loggers, and workers on site. Further, the human health risks associated with the tailings storage facility embankment breach were considered to be "very low". Groundwater did contain metals that exceeded drinking water standards including iron, manganese, arsenic, molybdenum, and sulfate. However, no wells that supply groundwater exist in the Hazeltine Corridor.[33]

2017

The HHRA report was published in May.[33] The Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) report was published in December and detailed the work done by Golder to understand the ecological significance of the tailings dam breach of 2014. The ERA report was completed as a component of the MPMC's remediation strategy to help inform rehabilitation work in affected areas. The ERA considered levels of metal contaminents in the soil, water, and sediment. Territorial and Aquatic risk assessments were concluded as part of the investigative work of the report. The report found excess concentrations of copper and vanadium in the soil however it was determined that the tailings were not acid generating and were unlikely to leach metals. The ERA determined the cause of some tree death post-breach and attributed a root smothering effect of the tailings effluent in the forested region. It was determined that tailings decreased soil aeration causing a poor environment for soil biota to support tree growth and survival. The food chain of local wildlife was modeled to determine if copper and vanadium exceeded standards. The cumulative dose according to these models was determined to be below a conservative threshold for most wildlife species. The report concluded low risk associated with copper and vanadium contamination. The bioavailability of the metals was likewise determined to be low. As part of the aquatic risk assessment, copper and arsenic were investigated in the sediment, while copper was the contaminant of potential concern investigated in the water of Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek, Quesnel Lake, and Quesnel River. It was determined that copper levels decreased below the accepted guideline through 2015 in both lakes and Quesnel River, but not in Hazeltine Creek which was the site of active remediation and restructuring. The plants, water-column invertebrates, and fish in Polley Lake and Quesnel Lake are not expected to face long-term effects of the 2014 breach, according to ERA report. Likewise, risk to fish-consuming wildlife was also determined to be low. The deep ecological benthic ecosystem was also considered to have little risk from copper as a limiting factor in the recovery of these organisms at the sediment layer. The ERA concluded that ecological risks associated with metals released by the dam breach and tailings spill are low.[34]

2018

Over 6 kilometers of new fish spawning and rearing habitats were installed in upper to middle Hazeltine Creek. The successful spawning of Rainbow Trout was later observed in 2018 and 2019 in upper Hazeltine Creek.[35]

2019

The Remediation Plan was prepared by Golder Associates for the MPMC and was submitted to the British Columbia Ministry of Environment & Climate Change Strategy. The was the final requirement of the Pollution Abatement Order which was lifted on 12 September 2019. The Mount Polley Review Panel determined that the environmental effect of the dam breach and tailing spill were the physical disruption of the effluents rather than chemical. MPMC turned its remediation focus to restore physical state of the affected sites. The remediation efforts include ongoing planting of trees and shrubs that are native to the local ecosystem in the riparian and upland areas along Hazeltine Creek. The Mount Polley remediation efforts have replanted 600,000 trees and shrubs to date. The risk from chemical contamination on the site was determine to be low to very low to the relevant terrestrial and aquatic environments. Remediation efforts also repaired 400 metres of shoreline at Quenels Lake and installed new fish habitats at that site. New wetlands were also installed at the site next to the tailings pond failure.[35]

Government monitoring, impact, and inspection

In 2010, provincial government funding was cut for resource management. Preceding the dam breach, Mount Polley was inspected 2013, but not 2011 or 2012. Bill Bennett, Minister of Energy and Mines, said "there is no evidence that the government's missed inspections were related to the failure of the dam [in 2014]".[20]

According to an Imperial Metals summary filed with Environment Canada in 2013, "there was 326 tonnes of nickel, over 400 tonnes of arsenic, 177 tonnes of lead and 18,400 tonnes of copper and its compounds placed in the tailings pond [last year]".[7] At a community meeting on 5 August 2014, the president of Imperial Metals stated "we regularly perform toxicity tests and we know this water is not toxic to rainbow trout."[7]

Water, sediment, and fish in Polley and Quesnel Lake are monitored by British Columbia government staff at the Ministry of Environment. Fish sampling in the months immediately proceeding the tailing spill revealed elevated levels of selenium that exceed guidelines for human consumption, though elevated levels of arsenic and copper were not considered a threat to human health. These levels were similar to levels found in 2013 before the tailings breach and considered likely due to local geology.[36]. Sediment testing near the tailings spill revealed elevated concentrations of copper, iron, manganese, arsenic, silver, selenium and vanadium. Yet, the government said tests in May 2014, prior to the tailings release, had shown elevated levels of the same elements.[37] By 2016, Ministry of Environment testing determined zero exceedances of its guideline levels for contaminants for both acquatic life and drinking water in Quesnel Lake.[25]

In the years after the tailing spill, the extent of the impact of the event has been largely determined. The British Columbia Ministry of Environment provides ongoing water monitoring of pH, conductivity, turbidity, total suspended solids, total dissolved solids, total organic carbon, hardness, alkalinity, nutrients, general ions, total and dissolved metals at the site.[25]

Imperial Metals history

Imperial Metals & Power Ltd was incorporated in British Columbia in December 1959. The company owns the Mount Polley open pit copper mine and gold mine along with the Huckleberry open pit copper mine near Houston, British Columbia and the Ruddock Creek zinc/lead project, near Kamloops, British Columbia.[38] In 2019, Imperial Metals sold its 70% stake in the Red Chris copper/gold mine to Newcrest Mining for $804 million.[39]

Imperial Metals temporarily suspended operations of the Mount Polley mine in 2019 due to declining copper prices. Environmental remediation work continues at the site. The mine's closure affects 250 workers and is the second cessation of work due to global copper prices. The first such closure occurred in 2001 and lasted until 2005.[40]

See also

- List of tailings dam failures

- Environmental remediation

- Williams Lake, British Columbia

References

- ↑ Jesse Allen and Adam Voiland (2014-08-15). "Dam breach at Mount Polley mine in British Columbia". NASA (Visible Earth). http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view.php?id=84202. Retrieved 2014-09-11.

- ↑ "What is in Mount Polley Tailings". Mount Polley Mining Corporation. https://www.imperialmetals.com/assets/docs/mt-polley/2016-04-06_CUB.pdf. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ "Conceptual hydrogeochemical characteristics of a calcite and dolomite acid mine drainage neutralised circumneutral groundwater system". Water Science. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110492917300036. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Mount Polley tailings pond situation update", Government of BC, Newsroom, 8 August 2014, http://www.newsroom.gov.bc.ca/2014/08/friday-aug-8---mount-polley-tailings-pond-situation-update.html, retrieved 8 August 2014

- ↑ Yaffe, Barbara (8 August 2014). "Alberta has reason to fret over B.C. tailings pond spill". Calgary Herald. https://calgaryherald.com/opinion/op-ed/Yaffe+Alberta+reason+fret+over+tailings+pond+spill/10102613/story.html. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ↑ Wise Uranium, 2018. The Mount Polley tailings dam failure (Canada)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 CBC News (6 August 2014), "Mount Polley mine tailings spill: Imperial Metals could face $1M fine", CBC News, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/mount-polley-mine-tailings-spill-imperial-metals-could-face-1m-fine-1.2728832, retrieved 8 August 2014

- ↑ Birchwater, Sage (5 August 2014). "Likely residents fear the worst after Mount Polley Mine disaster". The Williams Lake Tribune (Black Press, Inc.). http://www.wltribune.com/news/270019941.html.

- ↑ "Breach Of Tailings Pond Results In 'Largest Environmental Disaster In Modern Canadian History'". Australian Mine Safety Journal. 12 August 2014. http://www.amsj.com.au/news/breach-tailings-pond-results-largest-environmental-disaster-modern-canadian-history.

- ↑ Peter Koven (16 August 2014). "Imperial Metals plans debenture issue in wake of dam breach". National Post, syndicated via Star-Phoenix. https://thestarphoenix.com/business/Imperial+Metals+plans+debenture+issue+wake+breach/10124148/story.html.

- ↑ Peter Moskowitz (13 August 2014). "Mount Polley mine spill: a hazard of Canada's industry-friendly attitude?". The Guardian (Guardian News and Media). https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/aug/13/mount-polley-mine-spill-british-columbia-canada. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Joel Connelly (24 November 2014). "British Columbia mine breach 'a disaster' that will linger for years". Seattle pi (Hearst Seattle Media, LLC). http://blog.seattlepi.com/seattlepolitics/2014/11/24/british-columbia-mine-breach-a-disaster-recovery-will-take-years/#25734101=0. Retrieved 23 December 2014. "The scale of the initial disaster is tremendous: It is going to take a long time. This is the very, very beginnings of this,""

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 The Canadian Press (2014-08-09). "Water ban linked to Mount Polley mine tailings spill partially lifted". The Vancouver Sun. https://vancouversun.com/Water+linked+Mount+Polley+mine+tailings+spill+partially+lifted/10097584/story.html. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Mt. Polley Mine incident". BC Government Newsroom. http://www.newsroom.gov.bc.ca/2014/08/mt-polley-mine-incident.html. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Gordon Hoekstra (October 8, 2014). "Victoria breaking the law by not releasing mine reports: UVic law centre". Vancouver Sun (Postmedia Network Inc.). https://vancouversun.com/technology/Victoria+breaking+releasing+mine+reports+UVic+centre/10271696/story.html. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Kresnyak, Danny (April 29, 2015). "First Nation group launches protest to halt re-opening of Mount Polley mine". http://www.vancouverobserver.com/news/first-nation-group-launches-protest-halt-re-opening-mount-polley-mine.

- ↑ James Keller (21 August 2014). "'Lack of confidence' in B.C. from Alaskan fishing industry since Mount Polley breach". Globe and Mail (The Canadian Press). https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/lack-of-confidence-in-bc-from-alaskan-fishing-industry-since-mount-polley-breach/article20163310/. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Imperial Metals. "Mount Polley Updates-Tailings Breach Information". Imperial Metals Corporation. http://www.imperialmetals.com/s/Mt_Polley_Update.asp?ReportID=671041. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ↑ "Globe and Mail, "Mount Polley Spill taints Alaska-B.C. mine relations"". https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/mount-polley-spill-taints-alaska-bc-mine-relations/article22741378/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Justine Hunter (14 October 2014). "B.C. didn't inspect Mount Polley mine in 2010, 2011". The Globe and Mail (The Globe and Mail Inc). https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/bc-didnt-inspect-mount-polley-mine-in-2010-2011/article21084272/. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ CP (26 September 2018). "Three engineers to face disciplinary hearings in Mount Polley dam collapse". Vancouver Sun. https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/three-engineers-to-face-disciplinary-hearings-in-mount-polley-disaster. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "Remediation Plan Mount Polley Mine Perimeter Embankment Breach". Golder Associates Ltd.. 2019-03-29. https://www.imperialmetals.com/assets/docs/mt-polley/2019-03-golder-remediation-plan.pdf. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ↑ "Is Mount Polley Dumping Waste into Quesnel Lake?". https://mountpolley.com/is-mount-polley-dumping-waste-into-quesnel-lake/.

- ↑ Deborah Epps (2018-12-19). "Comparison of Continuous and Grab Sample Turbidity Data from the Quesnel River near Likely from August 2014 to May 2016". British Columbia Ministry of Environment. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/spills-and-environmental-emergencies/docs/mt-polley/sample-monitor/2018-12-19_memo_quesnel_lake_turbidity.pdf. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Deborah Epps (2016-12-08). "Quesnel Lake Water Quality for samples collected August 4, 2014 to August 30, 2016 compared to Drinking Water and Aquatic Life Guidelines". British Columbia Ministry of Environment. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/spills-and-environmental-emergencies/docs/mt-polley/sample-monitor/2016-12-08_final_ql_memo.pdf. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ↑ Deborah Epps (2016-10-19). "Quesnel River Water Quality for samples collected August 4, 2014 to August 4, 2016 compared to Drinking Water and Aquatic Life Guidelines". British Columbia Ministry of Environment. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/spills-and-environmental-emergencies/docs/mt-polley/sample-monitor/2016-10-19_memo_quesnelriver.pdf. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ↑ Deborah Epps (2016-10-19). "Polley Lake Water Quality for samples collected September 15, 2014 to August 25, 2016 compared to Drinking Water and Aquatic Life Guidelines". British Columbia Ministry of Environment. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/spills-and-environmental-emergencies/docs/mt-polley/sample-monitor/2016-11-21_final_pl_memo.pdf. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ↑ Deborah Epps (2016-01-20). "Hazeltine Creek and Quesnel River Water Quality for samples collected December 3 and December 10, 2015 compared to Drinking Water Guidelines". https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/spills-and-environmental-emergencies/docs/mt-polley/sample-monitor/hazeltine-creek-and-quesnel-river-dw.pdf. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ↑ Lyn Anglin. "How things were made right after the Mount Polley spill". Resource Works. https://www.resourceworks.com/polley-remediation.

- ↑ Sunny Dhillon (7 September 2014). "Reopen Mount Polley mine, union says". The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/reopen-mount-polley-mine-union-says/article20464893/. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "Post-Event Environmental Impact Assessment Report - Key Findings Report". Golder Associates Ltd.. 5 June 2015. https://www.imperialmetals.com/assets/docs/mt-polley/2015-06-18-MPMC-KFR.pdf. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "UPDATE: Mount Polley Mine Tailings Pond Breach – Remaining Water Use Restrictions Lifted". Interior Health. 13 July 2015. https://www.imperialmetals.com/assets/docs/mt-polley/2015-07-ihr-water.pdf. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 "Mount Polley Rehabilitation and Remediation Strategy - Human Health Risk Assessment". Golder Associates. 11 May 2017. https://www.imperialmetals.com/assets/docs/mt-polley/HHRA_11MAY_17.pdf. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ↑ "Mount Polley Rehabilitation and Remediation Strategy - Ecological Risk Assessment". Golder Associates. 15 December 2017. https://www.imperialmetals.com/assets/docs/mt-polley/Ecological-Risk-Assessment.pdf. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "2014 Breach Overview". Imperial Metals. https://www.imperialmetals.com/our-operations/mount-polley-mine/breach-overview.

- ↑ "Mount Polley spill: Testing finds elevated selenium in fish". CBC. 2014-08-22. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/mount-polley-spill-testing-finds-elevated-selenium-in-fish-1.2744343. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ↑ Canadian Press (2014-08-29). "Mount Polley mine breach: Elevated levels of chemical elements near tailings pond". Vancouver Sun. https://vancouversun.com/business/Mount+Polley+mine+breach+Elevated+levels+chemical+elements/10161351/story.html. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ↑ "Imperial Metals acquires 100 per cent of Huckleberry Mines". Prince George Daily News. 9 April 2017. https://pgdailynews.ca/index.php/2017/04/09/3468/.

- ↑ "Newcrest takes over at Red Chris JV". The Canadian Mining Journal. 16 August 2019. https://www.mining.com/newcrest-takes-over-at-red-chris-jv/. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ↑ "Imperial Metals to Suspend Operations at Mount Polley Mine". My Cariboo Now. 8 January 2019. https://www.mycariboonow.com/43690/operations-suspended-at-mount-polley-mine/. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

External links

- Web site of the review panel

- Final report of the review panel

- Mount Polley project site

- Government of British Columbia information site