Engineering:Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

| Shuttle Carrier Aircraft | |

|---|---|

NASA's Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 905 (front) and 911 (back) flying in formation in 2011 | |

| General information | |

| National origin | |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| Management | |

| Number built | 2 |

| Registration | N905NA[1], N911NA[2] |

| Aircraft carried | Space Shuttle, Phantom Ray |

| History | |

| Retired | 2012 |

| Developed from |

|

| Preserved at |

|

| Fate | Both aircraft preserved |

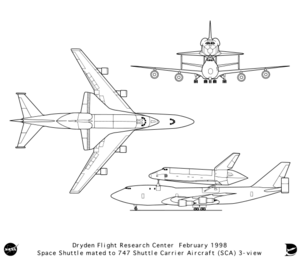

The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) are two extensively modified Boeing 747 airliners that NASA used to transport Space Shuttle orbiters. One (N905NA) is a 747-100 model, while the other (N911NA) is a short-range 747-100SR. Both are now retired.

The SCAs were used to ferry Space Shuttles from landing sites back to the Shuttle Landing Facility at the Kennedy Space Center. The orbiters were placed on top of the SCAs by Mate-Demate Devices, large gantry-like structures that hoisted the orbiters off the ground for post-flight servicing then mated them with the SCAs for ferry flights.

In approach and landing test flights conducted in 1977, the test shuttle Enterprise was released from an SCA during flight and glided to a landing under its own control.

Design and development

The Lockheed C-5 Galaxy was considered for the shuttle-carrier role by NASA but rejected in favor of the 747. This was due to the 747's low-wing design in comparison to the C-5's high-wing design, and also because the U.S. Air Force would have retained ownership of the C-5, while NASA could own the 747s outright. Lockheed had also proposed a heavily modified twin body C-5, to counter the Conroy Virtus concept.

The first aircraft, a Boeing 747-123 registered N905NA, was originally manufactured for American Airlines. With a decline in air traffic and failure to fill their 747s, American Airlines sold it to NASA. It still wore the visible American cheatlines while testing Enterprise in the 1970s. It was acquired in 1974 and initially used for trailing wake vortex research as part of a broader study by NASA Dryden, as well as Shuttle tests involving an F-104 flying in close formation and simulating a release from the 747.

The aircraft was extensively modified for NASA by Boeing in 1976.[3] While first-class seats were kept for NASA passengers, its main cabin and insulation were stripped,[4] and the fuselage was strengthened. Mounting struts were added on top of the 747, located to match the fittings on the Shuttle that attach it to the external fuel tank for launch.[5] With the Shuttle riding on top, the center of gravity was altered. Vertical stabilizers were added to the tail to improve stability when the Orbiter was being carried. The avionics and engines were also upgraded.

An internal escape slide was added behind the flight deck[6] in case of catastrophic failure mid-flight. In the event of a bail-out, explosives would be detonated to make an opening in the fuselage at the bottom of the slide, allowing the crew to exit through the slide and parachute to the ground. The slide system was removed following the Approach and Landing Tests because of concerns over the possibility of escaping crew members being ingested into an engine.[7]

Flying with the additional drag and weight of the Orbiter imposed significant fuel and altitude penalties. The range was reduced to 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km; 1,200 mi), compared to an unladen range of 5,500 nautical miles (10,200 km; 6,300 mi), requiring an SCA to stop several times to refuel on a transcontinental flight.[8] Without the Orbiter, the SCA needed to carry ballast to balance its center of gravity.[4] The SCA had an altitude ceiling of 15,000 feet (4,600 m) and a maximum cruise speed of Mach 0.6 with the orbiter attached.[8] A crew of 170 took a week to prepare the shuttle and SCA for flight.[9]

Studies were conducted to equip the SCA with aerial refueling equipment, a modification already made to the U.S. Air Force E-4 (modified 747-200s) and 747 tanker transports for the IIAF. However, during formation flying with a tanker aircraft to test refueling approaches, minor cracks were spotted on the tailfin of N905NA. While these were not likely to have been caused by the test flights, it was felt that there was no sense taking unnecessary risks. Since there was no urgent need to provide an aerial refueling capacity, the tests were suspended.

By 1983, SCA N905NA no longer carried the distinct American Airlines tricolor cheatline. NASA replaced it with its own livery, consisting of a white fuselage and a single blue cheatline.[10] That year, after secretly being fitted with an infrared countermeasures system to protect it from heat-seeking missiles,[11] it was also used to fly Enterprise on a tour in Europe, with refueling stops in Goose Bay, Canada; Keflavik, Iceland; England; and West Germany. It then went to the Paris Air Show.[9]

In 1988, in the wake of the Challenger accident, NASA procured a surplus 747SR-46 from Japan Airlines. Registered N911NA, it entered service with NASA in 1990 after undergoing modifications similar to N905NA. It was first used in 1991 to ferry the new shuttle Endeavour from the manufacturers in Palmdale, California to Kennedy Space Center.

Based at the Dryden Flight Research Center within Edwards Air Force Base in California[4] the two aircraft were functionally identical, although N911NA has five upper-deck windows on each side, while N905NA has only two.

The rear mounting points on both aircraft were labeled with humorous instructions to "attach orbiter here" or "place orbiter here", clarified by the precautionary note "black side down".[12][13]

Shuttle Carriers were capable of operating from alternative shuttle landing sites such as those in the United Kingdom, Spain, and France. Because Shuttle Carrier's range is reduced while mated to an orbiter, additional preparations such as removal of the payload from the orbiter may have been necessary to reduce its weight.[14]

Boeing transported its Phantom Ray unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) demonstrator from St. Louis, Missouri, to Edwards on a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft on December 11, 2010.[15]

Approach and Landing Tests

The Approach and Landing Tests were a series of taxi and flight trials of the prototype Space Shuttle Enterprise, conducted at Edwards Air Force Base in 1977. They verified the shuttle's flight characteristics when mated to the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft and when flying on its own, prior to the Shuttle system becoming operational. There were three taxi tests, eight captive flight tests and five free flight tests where the Enterprise was released from the SCA during flight and glided to a landing under its own control.[6][16]

Ferry flights

During the decades of Shuttle operations, the SCAs were most often used to transport the orbiters from Edwards Air Force Base, the shuttle's secondary landing site, to the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center where the orbiter was processed for another launch. The SCAs were also used to transport the orbiters between manufacturer Rockwell International and NASA during initial delivery and mid-life refits.[17]

At the end of the Space Shuttle program the SCA was used to deliver the retired orbiters from the Kennedy Space Center to their museums.

Discovery was flown to the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum at the Dulles International Airport on April 17, 2012, making low-level passes over Washington, D.C. landmarks before landing. Enterprise, which had been on display at the Smithsonian was transported to the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City on April 27, 2012, making low-level passes over the city's landmarks, before landing at John F. Kennedy International Airport, where it was transferred by barge to the museum.

The last ferry flight took Endeavour from Kennedy Space Center to Los Angeles between September 19 and 21, 2012 with refueling stops at Ellington Field and Edwards Air Force Base. After leaving Edwards the SCA with Endeavour performed low level flyovers above various landmarks across California, from Sacramento to the San Francisco Bay Area, before finally being delivered to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). From there the orbiter was transported through the streets of Los Angeles and Inglewood to its final destination, the California Science Center in Exposition Park.

Retirement

Shuttle Carrier N911NA was retired on February 8, 2012, after its final mission to the Dryden Flight Research Facility at Edwards Air Force Base in Palmdale, California, and was used as a source of parts for NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) aircraft, another modified Boeing 747.[18] N911NA is now preserved and on display at the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark in Palmdale, California as part of a long-term loan to the city from NASA.[19][20]

Shuttle Carrier N905NA was used to ferry the retired Space Shuttles to their respective museums. After delivering Endeavour to the Los Angeles International Airport in September 2012, the aircraft was flown to the Dryden Flight Research Facility, where NASA intended it to join N911NA as a source of spare parts for NASA's SOFIA aircraft,[18][21] but when NASA engineers surveyed N905NA they determined that it had few parts usable for SOFIA. In 2013, a decision was made to preserve N905NA and display it at Space Center Houston with the mockup Space Shuttle Independence mounted on its back.[22] N905NA was flown to Ellington Field where it was carefully dismantled, ferried to the Johnson Space Center in seven major pieces (a process called The Big Move), reassembled, and finally mated with the replica shuttle in August 2014.[23] The display, called Independence Plaza, opened to the public for the first time on January 23, 2016.[24]

Specifications

Data from Boeing 747-100 specifications,[25] Jenkins 2000[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: Four: two pilots, two flight engineers (one flight engineer when not carrying Shuttle)

- Capacity: 108,999.6 kg (240,303 lb) payload (externally-mounted Orbiter)

- Length: 231 ft 4 in (70.51 m)

- Wingspan: 195 ft 8 in (59.64 m)

- Height: 63 ft 5 in (19.33 m)

- Wing area: 5,500 sq ft (510 m2)

- Empty weight: 318,000 lb (144,242 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 710,000 lb (322,051 kg)

- Powerplant: 4 × Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7J turbofan engines, 50,000 lbf (220 kN) thrust each

Performance

- Cruise speed: 250 kn (290 mph, 460 km/h) / M0.6 with Shuttle Orbiter loaded

- Range: 1,150 nmi (1,320 mi, 2,130 km) with Shuttle Orbiter loaded

- Service ceiling: 15,000 ft (4,600 m) with Shuttle Orbiter loaded

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Engineering:Antonov An-225 Mriya – Soviet/Ukrainian heavy strategic cargo aircraft

- Astronomy:Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy – Infrared telescope system mounted on a converted Boeing 747 SP

- Engineering:Conroy Virtus – Proposed American large transport aircraft intended to carry the Space Shuttle

- Engineering:Myasishchev VM-T – Conversion of Soviet M-4 Molot bomber to carry outsized cargo

Related lists

- List of Boeing 747 operators

References

- ↑ "FAA Registry (N905NA)". http://registry.faa.gov/aircraftinquiry/NNum_Results.aspx?NNumbertxt=N905NA.

- ↑ "FAA Registry (N911NA)". http://registry.faa.gov/aircraftinquiry/NNum_Results.aspx?NNumbertxt=N911NA.

- ↑ Jenkins, Dennis R. (2000). Boeing 747-100/200/300/SP. AirlinerTech Series. 6. Specialty Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 1-58007-026-4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Brack, Jon (September 17, 2012). "Inside the Space Shuttle Carrier Aircraft". National Geographic. https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2012/09/17/inside-the-space-shuttle-carrier-aircraft/.

- ↑ "How was Enterprise held/released from the carrier 747 for the Shuttle approach and landing tests?". https://space.stackexchange.com/questions/25684/how-was-enterprise-held-released-from-the-carrier-747-for-the-shuttle-approach-a.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Approach and Landing Test Evaluation Team (February 1978). Space Shuttle Orbiter Approach and Landing Test: Final Evaluation Report. Houston: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. http://www.klabs.org/DEI/References/general/alt_final_report.pdf. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ↑ Creech, Gray (August 22, 2003). "Gravel Haulers: NASA's 747 Shuttle Carriers" (Press release). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Jenkins (2000), pp. 38–39.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gilette, Felix (August 9, 2005). "How the Space Shuttle Flies Home". Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2005/08/how-the-space-shuttle-flies-home.html.

- ↑ Comparison of photos taken in 1982 and 1983 at Airliners.net

- ↑ Rogoway, Joseph Trevithick and Tyler (January 27, 2022). "Space Shuttle Carrying 747 Was Secretly Modified To Defend Itself From Heat-Seeking Missiles (Updated)" (in en). https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/43681/space-shuttle-carrying-747-was-secretly-modified-to-defend-itself-from-heat-seeking-missiles.

- ↑ 2003 Edwards Air Force Base Air Show, see Shuttle Carrier images.

- ↑ Shuttle Carrier Aircraft N911NA album on Photobucket

- ↑ "Space Shuttle Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) Sites". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. December 2006. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/pdf/167472main_TALsites-06.pdf.

- ↑ Boeing Phantom Ray to catch shuttle ride at Lambert

- ↑ NASA Dryden Flight Research Center (1977). "Shuttle Enterprise Free Flight". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://grin.hq.nasa.gov/ABSTRACTS/GPN-2000-000218.html.

- ↑ "STS Chronology". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/technology/sts-newsref/sts-cron.html.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "NASA's Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 911's Final Flight". http://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/Features/sca_911_final_flight.html.

- ↑ Gibbs, Yvonne (September 12, 2014). "Final Journey: SCA 911 on Display at Davies Airpark" (Press release). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ↑ Gibbs, Yvonne (September 24, 2014). "NASA Armstrong Fact Sheet: Shuttle Carrier Aircraft" (in en). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://www.nasa.gov/centers/armstrong/news/FactSheets/FS-013-DFRC.html.

- ↑ Landis, Tony. "A graphic history of 35 years of Space Shuttle ferry flights now adorns the upper forward fuselage of NASA Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 905". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/images/content/636738main_ED12-0096-02.jpg.

- ↑ "Houston's Shuttle Gets New Name, Familiar Ride". Spaceflight Insider. October 8, 2013. http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/space-flight-news/houstons-shuttle-gets-new-name-familiar-ride/.

- ↑ Hays, Brooks (August 14, 2014). "Shuttle replica lifted and put on top of 747 carrier". SpaceDaily. United Press International. http://www.space-travel.com/reports/Shuttle_replica_lifted_and_put_on_top_of_747_carrier_999.html.

- ↑ Cofield, Calla (January 29, 2016). "Seeing Is Believing: Enormous Shuttle Program Artifact Inspires Wonder". Space.com. https://www.space.com/31776-independence-plaza-nasa-exhibit-awesomely-wonderful.html.

- ↑ Boeing 747-100 Technical Specifications, Boeing

Further reading

- Jenkins, Dennis R. (2001). Space Shuttle: The History of the National Space Transportation System, The First 100 Missions (3rd ed.). Midland Publishing. ISBN 0-9633974-5-1.

External links

- NASA fact sheet

- NASA SCA images

- Interview with SCA Pilot and Former Astronaut Gordon Fullerton

- Interview with SCA Crew Chief Pete Seidl

- "Hoot Gibson talks about John Kiker's 747 ferry model" on YouTube

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. TX-116-L, "Space Transportation System, Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, 2101 NASA Parkway, Houston, Harris County, TX", 8 photos, 3 color transparencies, 3 photo caption pages

Template:Outsized cargo aircraft Template:Space Shuttle Enterprise

|