Finance:Environmental effects of bitcoin

The environmental effects of bitcoin are significant. Bitcoin mining, the process by which bitcoins are created and transactions are finalized, is energy-consuming and results in carbon emissions as about half of the electricity used is generated through fossil fuels.[1] (As of 2022), bitcoin mining was estimated to be responsible for 0.2% of world greenhouse gas emissions,[2] and to represent 0.4% of global electricity consumption.[3] Moreover, bitcoins are mined on specialized computer hardware with a short lifespan, resulting in electronic waste.[4] The amount of electrical energy required and e-waste generated by bitcoin mining can be compared to countries like Greece or the Netherlands.[4][2] Bitcoin's environmental impact has attracted the attention of regulators, leading to incentives or restrictions in various jurisdictions.[5]

Greenhouse gas emissions

Mining as an electricity-intensive process

Bitcoin mining is a highly electricity-intensive proof-of-work process.[1][6] Miners run dedicated software to compete against each other and be the first to solve the current 10 minute block, yielding them a reward in bitcoins.[7] A transition to the proof-of-stake protocol, which has better energy efficiency, has been described as a sustainable alternative to bitcoin's scheme and as a potential solution to its environmental issues.[6] Bitcoin advocates oppose such a change, arguing that proof of work is needed to secure the network.[8]

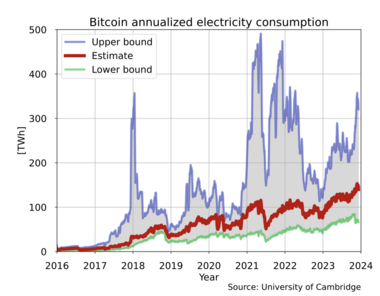

Bitcoin mining's distribution makes it difficult for researchers to identify the location of miners and electricity use. It is therefore difficult to translate energy consumption into carbon emissions.[3] (As of 2022), the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) estimates that bitcoin consumes 95.5 TWh (344 PJ) annually, representing 0.4% of the world's electricity consumption, ranking bitcoin mining between Belgium and the Netherlands in terms of electricity consumption.[3] A 2022 non-peer-reviewed commentary published in Joule estimated that bitcoin mining may result in annual carbon emission of 65 Mt CO

2, representing 0.2% of global emissions, which is comparable to the level of emissions of Greece.[2] A 2024 systematic review criticized the underlying assumptions of this estimate, arguing that the authors relied on old and partial data.[9]

Bitcoin mining energy mix

Until 2021, most bitcoin mining was done in China.[7] Chinese miners relied on cheap coal power in Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia during late autumn, winter and spring, migrating to regions with overcapacities in low-cost hydropower (like Sichuan and Yunnan) between May and October.[2] After China banned bitcoin mining in June 2021, its mining operations moved to other countries.[7] By August 2021, mining was concentrated in the U.S. (35%), Kazakhstan (18%), and Russia (11%) instead.[10] A study in Scientific Reports found that from 2016 to 2021, each US dollar worth of mined bitcoin caused 35 cents worth of climate damage, compared to 95 for coal, 41 for gasoline, 33 for beef, and 4 for gold mining.[11] The shift from coal resources in China to coal resources in Kazakhstan increased bitcoin's carbon footprint, as Kazakhstani coal plants use hard coal, which has the highest carbon content of all coal types.[2] Despite the ban, covert mining operations gradually came back to China, reaching 21% of global hashrate (As of 2022).[12]

Reducing the environmental impact of bitcoin is possible by mining only using clean electricity sources.[13] (As of 2023), according to Bloomberg Intelligence, renewables represent about half of global bitcoin mining sources,[14] while research by the nonprofit tech company WattTime estimated that US miners consumed 54% fossil fuel-generated power.[8] Still, experts and government authorities, such as the European Securities and Markets Authority and the European Central Bank, have suggested that using renewable energy for mining may limit the availability of clean energy for the general population.[1][15][16]

Bitcoin mining representatives argue that their industry creates opportunities for wind and solar companies,[17] leading to a debate on whether bitcoin could be an ESG investment.[18] According to a 2023 ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering paper, directing the surplus electricity from intermittent renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, to bitcoin mining could reduce electricity curtailment, balance the electrical grid, and increase the profitability of renewable energy plants—therefore accelerating the transition to sustainable energy and decreasing bitcoin's carbon footprint.[19] A 2023 review published in Resource and Energy Economics also concluded that bitcoin mining could increase renewable capacity but that it might increase carbon emissions and that mining bitcoin to provide demand response largely mitigated its environmental impact.[20] Two studies from 2023 and 2024 led by Fengqi You concluded that mining bitcoin off-grid during the precommercial phase (when a wind or solar farm is generating electricity but not yet integrated into the grid) could bring additional profits and therefore support renewable energy development and mitigate climate change.[21][22] Bitcoin mining may also incentivize the recommissioning of fossil fuel plants.[23] For instance, Greenidge Generation, a closed coal-fired power plant in New York State, was converted into natural gas in 2017 and started mining bitcoin in 2020 to monetize off-peak periods.[19] Such impact is difficult to quantify directly.[23]

Methane emissions

Bitcoin has been mined via electricity generated through the combustion of associated petroleum gas (APG), which is a methane-rich byproduct of crude oil drilling that is sometimes flared or released into the atmosphere.[24] Methane is a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 28 to 36 times greater than CO

2.[5] By converting more of the methane to CO

2 than flaring alone would, using APG generators reduces the APG's contribution to the greenhouse effect, but this practice still harms the environment.[5] In places such as Colorado, where flaring is prohibited, this practice has allowed more oil drills to operate by offsetting costs, delaying fossil fuel phase-out.[5] Commenting on one pilot project with ExxonMobil, political scientist Paasha Mahdavi noted in 2022 that this process could potentially allow oil companies to report lower emissions by selling gas leaks, shifting responsibility to buyers and avoiding a real reduction commitment.[25]

Comparison to other payment systems

In a 2023 study published in Ecological Economics, researchers from the International Monetary Fund estimated that the global payment system represented about 0.2% of global electricity consumption, comparable to the consumption of Portugal or Bangladesh.[26] For bitcoin, energy used is estimated around 500 kilowatt-hours per transaction, compared to 0.001 kWh for credit cards (not including consumption from the merchant's bank, which receives the payment).[26] However, bitcoin's energy expenditure is not directly linked to the number of transactions. Layer 2 solutions, like the Lightning Network, and batching, allow bitcoin to process more payments than the number of on-chain transactions suggests.[26][27] For instance, in 2022, bitcoin processed 100 million transactions per year, representing 250 million payments.[26]

Electronic waste

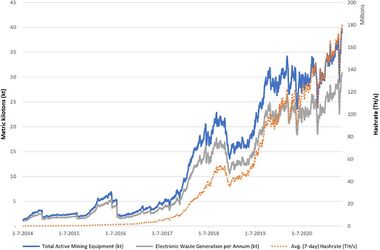

Bitcoins are usually mined on specialized computing hardware, called application-specific integrated circuits, with no alternative use beyond bitcoin mining.[4] Due to the consistent increase of the bitcoin network's hashrate, mining devices are estimated to have an average lifespan of 1.3 years until they become unprofitable and need to be replaced, resulting in significant electronic waste.[4] (As of 2021), bitcoin's annual e-waste was estimated to be over 30,000 tonnes, which is comparable to the small IT equipment waste produced by the Netherlands.[4] Each bitcoin transaction was estimated to result in 272 g (9.6 oz) of e-waste.[4]

Water footprint

According to a 2023 non-peer-reviewed commentary, bitcoin's water footprint reached 1,600 gigalitres (5.7×1010 cu ft) in 2021, due to direct water consumption on site and indirect consumption from electricity generation.[28] The author notes that this water footprint could be mitigated by using immersion cooling and power sources that do not require freshwater such as wind, solar, and thermoelectric power generation with dry cooling.[28]

Regulatory responses

China's 2021 bitcoin mining ban was partly motivated by its role in illegal coal mining and environmental concerns.[29][30]

In September 2022, the US Office of Science and Technology Policy highlighted the need for increased transparency about electricity usage, greenhouse gas emissions, and e-waste.[31] In November 2022, the US Environmental Protection Agency confirmed working on the climate impacts of cryptocurrency mining.[32] In the US, New York State banned new fossil fuel mining plants with a two-year moratorium, citing environmental concerns,[5] while Iowa, Kentucky, Montana, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas , and Wyoming encourage bitcoin mining with tax breaks.[5][33] Texas incentives aim to cut methane emissions from flared gas using bitcoin mining.[33]

In Canada, due to high demand from the industry and concerned that their renewable electricity could be better used, the provinces Manitoba and British Columbia paused new connections of bitcoin mining facilities to the hydroelectric grid in late 2022 for 18 months while Hydro-Québec increased prices and capped usage for bitcoin miners.[34]

In October 2022, due to the global energy crisis, the European Commission invited member states to lower the electricity consumption of crypto-asset miners and end tax breaks and other incentives benefiting them.[35]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Huang, Jon; O'Neill, Claire; Tabuchi, Hiroko (3 September 2021). "Bitcoin Uses More Electricity Than Many Countries. How Is That Possible?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/09/03/climate/bitcoin-carbon-footprint-electricity.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 de Vries et al. 2022, p. 499.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Messina, Irene (31 August 2023). "Bitcoin electricity consumption: an improved assessment" (in en-GB). https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/2023/bitcoin-electricity-consumption.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 de Vries, Alex; Stoll, Christian (December 2021). "Bitcoin's growing e-waste problem". Resources, Conservation and Recycling 175: 105901. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105901. ISSN 0921-3449. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344921005103. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Stoll, Christian; Klaaßen, Lena; Gallersdörfer, Ulrich; Neumüller, Alexander (June 2023). Climate Impacts of Bitcoin Mining in the U.S. (Report). Working Paper Series. MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep51839. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wendl, Moritz; Doan, My Hanh; Sassen, Remmer (15 January 2023). "The environmental impact of cryptocurrencies using proof of work and proof of stake consensus algorithms: A systematic review". Journal of Environmental Management 326 (Pt A): 116530. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116530. ISSN 0301-4797. PMID 36372031. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030147972202103X. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 de Vries et al. 2022, p. 498.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dance, Gabriel J. X.; Wallace, Tim; Levitt, Zach (2023-04-10). "The Real-World Costs of the Digital Race for Bitcoin" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/09/business/bitcoin-mining-electricity-pollution.html.

- ↑ Sai, Ashish Rajendra; Vranken, Harald (2024). "Promoting rigor in blockchain energy and environmental footprint research: A systematic literature review". Blockchain: Research and Applications 5 (1): 100169. doi:10.1016/j.bcra.2023.100169. ISSN 2096-7209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcra.2023.100169.

- ↑ de Vries et al. 2022, Data S1.

- ↑ Jones, Benjamin A.; Goodkind, Andrew L.; Berrens, Robert P. (29 September 2022). "Economic estimation of Bitcoin mining's climate damages demonstrates closer resemblance to digital crude than digital gold" (in en). Scientific Reports 12 (1): 14512. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-18686-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 36175441. Bibcode: 2022NatSR..1214512J.

- ↑ Akhtar, Tanzeel; Shukla, Sidhartha (17 May 2022). "China Makes a Comeback in Bitcoin Mining Despite Government Ban" (in en). Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-17/china-makes-a-comeback-in-bitcoin-mining-despite-government-ban.

- ↑ de Vries et al. 2022, pp. 501–502.

- ↑ Coutts, Jamie Douglas (2023-09-14). "Bitcoin and the Energy Debate: Bitcoin's Energy Narrative Reverses as Sustainables Exceed 50%".

- ↑ Szalay, Eva (19 January 2022). "EU should ban energy-intensive mode of crypto mining, regulator says". Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/8a29b412-348d-4f73-8af4-1f38e69f28cf.

- ↑ Gschossmann, Isabella; van der Kraaij, Anton; Benoit, Pierre-Loïc; Rocher, Emmanuel (11 July 2022). "Mining the environment – is climate risk priced into crypto-assets?" (in en). Macroprudential Bulletin (European Central Bank) (18). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/financial-stability/macroprudential-bulletin/html/ecb.mpbu202207_3~d9614ea8e6.en.html. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ↑ Yaffe-Bellany, David (March 22, 2022). "Bitcoin Miners Want to Recast Themselves as Eco-Friendly". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/22/technology/bitcoin-miners-environment-crypto.html.

- ↑ Mundy, Simon; Yoshida, Kaori (2023-12-12). "COP28: The struggle to say 'fossil fuels' out loud". https://www.ft.com/content/b26b5af8-0cf1-424b-bafc-d2ce4760a28c.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Velický, Matěj (27 February 2023). "Renewable Energy Transition Facilitated by Bitcoin" (in en). ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 11 (8): 3160–3169. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c06077. ISSN 2168-0485.

- ↑ Bruno, August; Weber, Paige; Yates, Andrew J. (August 2023). "Can Bitcoin mining increase renewable electricity capacity?". Resource and Energy Economics 74: 101376. doi:10.1016/j.reseneeco.2023.101376. ISSN 0928-7655.

- ↑ Lal, Apoorv; Zhu, Jesse; You, Fengqi (2023-11-13). "From Mining to Mitigation: How Bitcoin Can Support Renewable Energy Development and Climate Action" (in en). ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 11 (45): 16330–16340. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c05445. ISSN 2168-0485. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c05445. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ↑ Lal, Apoorv; Niaz, Haider; Liu, J. Jay; You, Fengqi (2024-02-01). "Can bitcoin mining empower energy transition and fuel sustainable development goals in the US?" (in en). Journal of Cleaner Production 439: 140799. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140799. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959652624002464.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Corbet, Shaen; Yarovaya, Larisa (24 August 2020). "The environmental effects of cryptocurrencies" (in en). Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technology. De Gruyter. p. 154. doi:10.1515/9783110660807-009. ISBN 978-3-11-066080-7. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110660807-009/html?lang=en. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ↑ Lorenzato, Gianni; Tordo, Silvana; Howells, Huw Martyn; Berg, Berend van den (2022-05-20) (in en). Financing Solutions to Reduce Natural Gas Flaring and Methane Emissions. World Bank. pp. 98–104. ISBN 978-1-4648-1850-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=TU9uEAAAQBAJ. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ↑ Calma, Justine (4 April 2022). "Why fossil fuel companies see green in Bitcoin mining projects / And why it's risky business". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2022/5/4/23055761/exxonmobil-cryptomining-bitcoin-methane-gas.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Agur, Itai; Lavayssière, Xavier; Villegas Bauer, Germán; Deodoro, Jose; Martinez Peria, Soledad; Sandri, Damiano; Tourpe, Hervé (October 2023). "Lessons from crypto assets for the design of energy efficient digital currencies" (in en). Ecological Economics 212: 107888. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107888. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0921800923001519. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ↑ Heinonen, Henri T.; Semenov, Alexander; Veijalainen, Jari; Hamalainen, Timo (14 July 2022). "A Survey on Technologies Which Make Bitcoin Greener or More Justified". IEEE Access 10: 74792–74814. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3190891. Bibcode: 2022IEEEA..1074792H.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 de Vries, Alex (November 29, 2023). "Bitcoin's growing water footprint". Cell Reports Sustainability. doi:10.1016/j.crsus.2023.100004. https://www.cell.com/cell-reports-sustainability/fulltext/S2949-7906(23)00004-6.

- ↑ "China's Crypto Mining Crackdown Followed Deadly Coal Accidents" (in en). Bloomberg.com. 2021-05-26. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-26/china-s-crypto-mining-crackdown-followed-deadly-coal-accidents.

- ↑ Zhu, Mingzhe (2023-04-15). "The 'bitcoin judgements' in China: Promoting climate awareness by judicial reasoning?" (in en). Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 32 (1): 158–162. doi:10.1111/reel.12496. ISSN 2050-0386. https://hal.science/hal-04043981/document.

- ↑ OSTP (8 September 2022), Climate and Energy Implications of Crypto-Assets in the United States, White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/09-2022-Crypto-Assets-and-Climate-Report.pdf, retrieved 28 December 2022

- ↑ Lee, Stephen (21 November 2022). "EPA Acknowledges Plans to Look at Crypto Energy Usage, Emissions" (in en). https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/epa-acknowledges-plans-to-look-at-crypto-energy-usage-emissions.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Bologna, Michael J.. "Texas Offers New Tax Benefit to Attract Bitcoin Miners" (in en). https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report-state/texas-offers-new-tax-benefit-to-attract-bitcoin-miners.

- ↑ Paas-Lang, Christian (Mar 18, 2023). "Crypto at a crossroads: Some provinces are wary of the technology's vast appetite for electricity". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/crypto-mining-electricity-provinces-1.6780907.

- ↑ Dekeyrel, Simon; Fessler, Melanie (2023-09-27). "Digitalisation: an enabler for the clean energy transition" (in en). Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law: 1–25. doi:10.1080/02646811.2023.2254103. ISSN 0264-6811. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02646811.2023.2254103. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

Works cited

- de Vries, Alex; Gallersdörfer, Ulrich; Klaaßen, Lena; Stoll, Christian (16 March 2022). "Revisiting Bitcoin's carbon footprint". Joule 6 (3): 498–502. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2022.02.005. ISSN 2542-4351.

|