Finance:Market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural towns with a hinterland of villages are still commonly called market towns, as sometimes reflected in their names (e.g. Downham Market, Market Rasen, or Market Drayton).

Modern markets are often in special halls, but this is a relatively recent development. Historically the markets were open-air, held in what is usually called (regardless of its actual shape) the market square or market place, sometimes centred on a market cross (mercat cross in Scotland). They were and are typically open one or two days a week. In the modern era, the rise of permanent retail establishments reduced the need for periodic markets.

History

Examples

See also

References

- ↑ "circa". Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/circa.

External links

The primary purpose of a market town is the provision of goods and services to the surrounding locality.[1] Although market towns were known in antiquity, their number increased rapidly from the 12th century. Market towns across Europe flourished with an improved economy, a more urbanised society and the widespread introduction of a cash-based economy.[2] Domesday Book of 1086 lists 50 markets in England. Some 2,000 new markets were established between 1200 and 1349.[3] The burgeoning of market towns occurred across Europe around the same time.

Initially, market towns most often grew up close to fortified places, such as castles or monasteries, not only to enjoy their protection, but also because large manorial households and monasteries generated demand for goods and services.[4] Historians term these early market towns "prescriptive market towns" in that they may not have enjoyed any official sanction such as a charter, but were accorded market town status through custom and practice if they had been in existence prior to 1199.[5] From an early stage, kings and administrators understood that a successful market town attracted people, generated revenue and would pay for the town's defences.[6] In around the 12th century, European kings began granting charters to villages allowing them to hold markets on specific days.[7]

Framlingham in Suffolk is a notable example of a market situated near a fortified building. Additionally, markets were located where transport was easiest, such as at a crossroads or close to a river ford, for example, Cowbridge in the Vale of Glamorgan. When local railway lines were first built, market towns were given priority to ease the transport of goods. For instance, in Calderdale, West Yorkshire, several market towns close together were designated to take advantage of the new trains. The designation of Halifax, Sowerby Bridge, Hebden Bridge, and Todmorden is an example of this.

A number of studies have pointed to the prevalence of the periodic market in medieval towns and rural areas due to the localised nature of the economy. The marketplace was the commonly accepted location for trade, social interaction, transfer of information and gossip. A broad range of retailers congregated in market towns – peddlers, retailers, hucksters, stallholders, merchants and other types of trader. Some were professional traders who occupied a local shopfront such as a bakery or alehouse, while others were casual traders who set up a stall or carried their wares around in baskets on market days. Market trade supplied for the needs of local consumers whether they were visitors or local residents.[8]

Braudel and Reynold have made a systematic study of European market towns between the 13th and 15th century. Their investigation shows that in regional districts markets were held once or twice a week while daily markets were common in larger cities. Over time, permanent shops began opening daily and gradually supplanted the periodic markets, while peddlers or itinerant sellers continued to fill in any gaps in distribution. The physical market was characterised by transactional exchange and bartering systems were commonplace. Shops had higher overhead costs, but were able to offer regular trading hours and a relationship with customers and may have offered added value services, such as credit terms to reliable customers. The economy was characterised by local trading in which goods were traded across relatively short distances. Braudel reports that, in 1600, grain moved just 5–10 miles (8.0–16.1 km); cattle 40–70 miles (64–113 km); wool and woollen cloth 20–40 miles (32–64 km). However, following the European age of discovery, goods were imported from afar – calico cloth from India, porcelain, silk and tea from China, spices from India and South-East Asia and tobacco, sugar, rum and coffee from the New World.[9]

The importance of local markets began to decline in the mid-16th century. Permanent shops which provided more stable trading hours began to supplant the periodic market.[10] In addition, the rise of a merchant class led to the import and exports of a broad range of goods, contributing to a reduced reliance on local produce. At the centre of this new global mercantile trade was Antwerp, which by the mid-16th century, was the largest market town in Europe.[11]

A good number of local histories of individual market towns can be found. However, more general histories of the rise of market-towns across Europe are much more difficult to locate. Clark points out that while a good deal is known about the economic value of markets in local economies, the cultural role of market-towns has received scant scholarly attention.[12]

By country

Czech Republic

Denmark

In Denmark, the concept of the market town (Danish: købstad) emerged during the Iron Age. It is not known which was the first Danish market town, but Hedeby (part of modern-day Schleswig-Holstein) and Ribe were among the first. As of 1801, there were 74 market towns in Denmark (for a full list, see this table at Danish Wikipedia). The last town to gain market rights (Danish: købstadsprivilegier) was Skjern in 1958. At the municipal reform of 1970, market towns were merged with neighboring parishes, and the market towns lost their special status and privileges, though many still advertise themselves using the moniker of købstad and hold public markets on their historic market squares.

-

Market day on the market square in Ribe in Jutland, 1897-98

-

Market day on the Haymarket in Copenhagen, c. 1900

-

Market day on the market square in Sorø on Zealand, 1915

-

Public market on the historic market square in Aakirkeby on Bornholm, 2010

-

Public market on the historic market square in Køge on Zealand, 2015

-

Public market on the historic market square in Svendborg on Funen, 2019

German-language area

The medieval right to hold markets (German: Marktrecht) is reflected in the prefix Markt of the names of many towns in Austria and Germany, for example, Markt Berolzheim or Marktbergel. Other terms used for market towns were Flecken in northern Germany, or Freiheit and Wigbold in Westphalia.

Market rights were designated as long ago as during the Carolingian Empire.[13] Around 800, Charlemagne granted the title of a market town to Esslingen am Neckar.[14] Conrad created a number of market towns in Saxony throughout the 11th century and did much to develop peaceful markets by granting a special 'peace' to merchants and a special and permanent 'peace' to market-places.[15] With the rise of the territories, the ability to designate market towns was passed to the princes and dukes, as the basis of German town law.

The local ordinance status of a market town (Marktgemeinde or Markt) is perpetuated through the law of Austria, the German state of Bavaria, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. Nevertheless, the title has no further legal significance, as it does not grant any privileges.

-

Market hall, Invalidenstraße, Berlin, Germany

-

Market place, Weeze, Germany

-

Market place, with fountain, Schmölln, Germany

-

Market place, Floridsdorf, Austria, c. 1895

Hungary

In Hungarian, the word for market town "mezőváros" means literally "pasture town" and implies that it was unfortified town: they were architecturally distinguishable from other towns by the lack of town walls. Most market towns were chartered in the 14th and 15th centuries and typically developed around 13th-century villages that had preceded them. A boom in the raising of livestock may have been a trigger for the upsurge in the number of market towns during that period.

Archaeological studies suggest that the ground plans of such market towns had multiple streets and could also emerge from a group of villages or an earlier urban settlement in decline, or be created as a new urban centre.[16]

Frequently, they had limited privileges compared to free royal cities. Their long-lasting feudal subordination to landowners or the church is also a crucial difference.[17]

The successors of these settlements usually have a distinguishable townscape. The absence of fortification walls, sparsely populated agglomerations, and their tight bonds with agricultural life allowed these towns to remain more vertical compared to civitates. The street-level urban structure varies depending on the era from which various parts of the city originate. Market towns were characterized as a transition between a village and a city, without a unified, definite city core. A high level of urban planning only marks an era starting from the 17th-18th centuries.[18] This dating is partially related to the modernization and resettlement waves after the liberation of Ottoman Hungary.

-

Hungarian fruit market, original drawing by Wilhelm Hahn, 1868

-

Main market street in Miskolc, 1884

-

Heti vásár (weekly market) at Nagykanizsa, 1901

Iceland

While Iceland was under Danish rule, Danish merchants held a monopoly on trade with Iceland until 1786. With the abolishment of the trading monopoly, six market town (Icelandic kaupstaður) were founded around the country. All of them, except for Reykjavík, would lose their market rights in 1836. New market towns would be designated by acts from Alþingi in the 19th and 20th century. In the latter half of the 20th century, the special rights granted to market towns mostly involved a greater autonomy in fiscal matters and control over town planning, schooling and social care. Unlike rural municipalities, the market towns were not considered part of the counties.

The last town to be granted market rights was Ólafsvík in 1983 and from that point there were 24 market towns until a municipal reform in 1986 essentially abolished the concept. Many of the existing market towns would continue to be named kaupstaður even after the term lost any administrative meaning.

Norway

In Norway, the medieval market town (Norwegian: kjøpstad and kaupstad from the Old Norse kaupstaðr) was a town which had been granted commerce privileges by the king or other authorities. The citizens in the town had a monopoly over the purchase and sale of wares, and operation of other businesses, both in the town and in the surrounding district.

Norway developed market towns at a much later period than other parts of Europe. The reasons for this late development are complex but include the sparse population, lack of urbanisation, no real manufacturing industries and no cash economy.[19] The first market town was created in 11th century Norway, to encourage businesses to concentrate around specific towns. King Olaf established a market town at Bergen in the 11th century, and it soon became the residence of many wealthy families.[20] Import and export was to be conducted only through market towns, to allow oversight of commerce and to simplify the imposition of excise taxes and customs duties. This practice served to encourage growth in areas which had strategic significance, providing a local economic base for the construction of fortifications and sufficient population to defend the area. It also served to restrict Hanseatic League merchants from trading in areas other than those designated.

Norway included a subordinate category to the market town, the "small seaport" (Norwegian lossested or ladested), which was a port or harbor with a monopoly to import and export goods and materials in both the port and a surrounding outlying district. Typically, these were locations for exporting timber, and importing grain and goods. Local farm goods and timber sales were all required to pass through merchants at either a small seaport or a market town prior to export. This encouraged local merchants to ensure trading went through them, which was so effective in limiting unsupervised sales (smuggling) that customs revenues increased from less than 30% of the total tax revenues in 1600 to more than 50% of the total taxes by 1700.

Norwegian "market towns" died out and were replaced by free markets during the 19th century. After 1952, both the "small seaport" and the "market town" were relegated to simple town status.

-

Fish market, Bergen, Norway, c. 1890

-

Market and customs house, Porsgrunn, c. 1891-1910

-

Market square, Youngstorget Nytorvet, c. 1915-20

-

Norwegian market, Skibotn in Storfjord Municipality, Troms county, 1917

-

Norwegian Market, c. 1921-35

-

Market (illustration), c. 1927

-

Traditional Winter market at Røros, 2001

-

Market, Tønsberg, Norway, 2010

Poland

Miasteczko (lit. small town) was a historical type of urban settlement similar to a market town in the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. After the partitions of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at the end of the 18th-century, these settlements became widespread in the Austrian, German and Russian Empires. The vast majority of miasteczkos had significant or even predominant Jewish populations; these are known in English under the Yiddish term shtetl. Miasteczkos had a special administrative status other than that of town or city.[21][22]

United Kingdom and Ireland

England and Wales

From the time of the Norman conquest, the right to award a charter was generally seen to be a royal prerogative. However, the granting of charters was not systematically recorded until 1199.[23] Once a charter was granted, it gave local lords the right to take tolls and also afforded the town some protection from rival markets. When a chartered market was granted for specific market days, a nearby rival market could not open on the same days.[24] Across the boroughs of England, a network of chartered markets sprang up between the 12th and 16th centuries, giving consumers reasonable choice in the markets they preferred to patronise.[25]

Until about 1200, markets were often held on Sundays, the day when the community congregated in town to attend church. Some of the more ancient markets appear to have been held in churchyards. At the time of the Norman conquest, the majority of the population made their living through agriculture and livestock farming. Most lived on their farms, situated outside towns, and the town itself supported a relatively small population of permanent residents. Farmers and their families brought their surplus produce to informal markets held on the grounds of their church after worship. By the 13th century, however, a movement against Sunday markets gathered momentum, and the market gradually moved to a site in town's centre and was held on a weekday.[26] By the 15th century, towns were legally prohibited from holding markets in church-yards.[27]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Colchester is England's oldest recorded market town, dating to at least the time of the Roman occupation of Britain's southern regions.[28] Another ancient market town is Cirencester, which held a market in late Roman Britain. The term derived from markets and fairs first established in 13th century after the passage of Magna Carta, and the first laws towards a parlement. The Provisions of Oxford of 1258 were only possible because of the foundation of a town and university at a crossing-place on the River Thames up-river from Runnymede, where it formed an oxbow lake in the stream. Early patronage included Thomas Furnyvale, lord of Hallamshire, who established a Fair and Market in 1232. Travelers were able to meet and trade wares in relative safety for a week of "fayres" at a location inside the town walls. The reign of Henry III witnessed a spike in established market fairs. The defeat of de Montfort increased the sample testing of markets by Edward I the "lawgiver", who summoned the Model Parliament in 1295 to perambulate the boundaries of forest and town.

Market towns grew up at centres of local activity and were an important feature of rural life and also became important centres of social life, as some place names suggest: Market Drayton, Market Harborough, Market Rasen, Market Deeping, Market Weighton, Chipping Norton, Chipping Ongar, and Chipping Sodbury – chipping was derived from a Saxon verb meaning "to buy".[29] A major study carried out by the University of London found evidence for least 2,400 markets in English towns by 1516.[30]

The English system of charters established that a new market town could not be created within a certain travelling distance of an existing one. This limit was usually a day's worth of travelling (approximately 10 kilometres (6.2 mi)) to and from the market.[31] If the travel time exceeded this standard, a new market town could be established in that locale. As a result of the limit, official market towns often petitioned the monarch to close down illegal markets in other towns. These distances are still law in England today. Other markets can be held, provided they are licensed by the holder of the Royal Charter, which tends currently to be the local town council. Failing that, the Crown can grant a licence.[32]

As the number of charters granted increased, competition between market towns also increased. In response to competitive pressures, towns invested in a reputation for quality produce, efficient market regulation and good amenities for visitors such as covered accommodation. By the thirteenth century, counties with important textile industries were investing in purpose built market halls for the sale of cloth. Specific market towns cultivated a reputation for high quality local goods. For example, London's Blackwell Hall became a centre for cloth, Bristol became associated with a particular type of cloth known as Bristol red, Stroud was known for producing fine woollen cloth, the village of Worsted, near North Walsham became synonymous with a type of yarn; Banbury and Essex were strongly associated with cheeses.[33]

A study on the purchasing habits of the monks and other individuals in medieval England, suggests that consumers of the period were relatively discerning. Purchase decisions were based on purchase criteria such as consumers' perceptions of the range, quality, and price of goods. This informed decisions about where to make their purchases.[34]

As traditional market towns developed, they featured a wide main street or central market square. These provided room for people to set up stalls and booths on market days. Often the town erected a market cross in the centre of the town, to obtain God's blessing on the trade. Notable examples of market crosses in England are the Chichester Cross, Malmesbury Market Cross and Devizes, Wiltshire. Market towns often featured a market hall, as well, with administrative or civic quarters on the upper floor, above a covered trading area. Market towns with smaller status include Minchinhampton, Nailsworth, and Painswick near Stroud, Gloucestershire.[35]

A "market town" may or may not have rights concerning self-government that are usually the legal basis for defining a "town". For instance, Newport, Shropshire, is in the borough of Telford and Wrekin but is separate from Telford. In England, towns with such rights are usually distinguished with the additional status of borough. It is generally accepted that, in these cases, when a town was granted a market, it gained the additional autonomy conferred to separate towns.[36] Many of the early market towns have continued operations into recent times. For instance, Northampton market received its first charter in 1189 and markets are still held in the square to this day.[37]

The National Market Traders Federation, situated in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, has around 32,000 members[38] and close links with market traders' federations throughout Europe. According to the UK National Archives,[39] there is no single register of modern entitlements to hold markets and fairs, although historical charters up to 1516 are listed in the Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales.[40] William Stow's 1722 Remarks on London includes "A List of all the Market Towns in England and Wales; with the Days of the Week whereon kept".[41][42]

-

Holyhead market in Wales, woodcut, 1840

-

Birmingham Market Charters 1166 and 1189

-

Market cross, Lambourn erected in 1446

-

Salisbury chartered market

-

Sedbergh chartered market

-

Market Square, Huntingdon.

-

Northampton Market, established in around 1255

-

Altrincham, Chartered Market

-

Corner of the market square in Horncastle, given its charter in the 13th century

-

Farmers' market on Monnow Bridge, Wales, 2008

Ireland

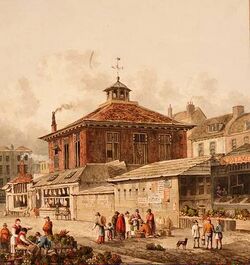

Market houses were a common feature across the island of Ireland. These often arcaded buildings performed marketplace functions, frequently with a community space on the upper floor. The oldest surviving structures date from the mid-17th century.

Scotland

In Scotland, borough markets were held weekly from an early stage. A King's market was held at Roxburgh on a specific day from about the year 1171; a Thursday market was held at Glasgow, a Saturday market at Arbroath, and a Sunday market at Brechin.[43]

In Scotland, market towns were often distinguished by their mercat cross: a place where the right to hold a regular market or fair was granted by a ruling authority (either royal, noble, or ecclesiastical). As in the rest of the UK, the area in which the cross was situated was almost always central: either in a square; or in a broad, main street. Towns which still have regular markets include: Inverurie, St Andrews, Selkirk, Wigtown, Kelso, and Cupar. Not all still possess their mercat cross (market cross).[44]

-

Kelso Farmers Market, Scotland with cobbled square in the foreground

-

Square in front of St Giles' Church, Elgin, is the site of a medieval market

-

Orkney Auction Mart, Hatston Industrial Estate

-

Weekly Farmers' Market at Castle Terrace, Edinburgh

In art and literature

Dutch painters of Antwerp took great interest in market places and market towns as subject matter from the 16th century. Pieter Aertsen was known as the "great painter of the market"[45] Painters' interest in markets was due, at least in part, to the changing nature of the market system at that time. With the rise of the merchant guilds, the public began to distinguish between two types of merchant, the meerseniers which referred to local merchants including bakers, grocers, sellers of dairy products and stall-holders, and the koopman, which described a new, emergent class of trader who dealt in goods or credit on a large scale. Paintings of every day market scenes may have been an affectionate attempt to record familiar scenes and document a world that was in danger of being lost.[46]

Paintings and drawings of market towns and market scenes

-

Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen, 1550

-

Rustic Market (Nundinae Rusticorum) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1555–56

-

Fish Market by Joachim Beuckelaer, 1568

-

At the Market by Jonge Lange, 1584

-

Peasants going to the market, Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1602

-

Vegetable market in Holland, by Sybrand van Beest, 1648

-

Fruit and vegetable market, Holland by Sybrand van Beest 1652

-

Village Market with the Quack by Cornelis Pietersz Bega, 1654

-

Market Scene by Jan van Horst, 1569

-

Flemish Market and Washing Place by Joos de Momper, first half 17th century

-

Market Square in Bruges by Jan Baptist van Meunincxhove, 1696

-

A Fish Market in a Village Square by Barent Gael, n.d. (late 17th century)

-

A Poultry Market Before a Village Inn by Barent Gael, n.d. (late 17th century)

-

Market by Alessandro Magnasco, first half 18th century

-

Market at Aberystwith, sepia print by Samuel Ireland, 1797

-

'Returning from Market', oil painting by Augustus Wall Callcott, c. 1834

-

The Fish market in Woudrichem by Jan Weissenbruch, 1850

-

Market Day at Zaltbommel by Elias Pieter Van Bommel, 1852

-

A market day in Bangor by John J Walker, 1856

-

A market scene in Constantinople by Ivan Aivazovsky, 1860

-

Grote Markt, Zwolle by Cornelis Springer, 1862

-

Town hall and market by Cornelis Springer, 1864 (detail)

-

Pwllheli Market in Wales, watercolour by Frances Elizabeth Wynne, c. 1866

-

A Moonlit Vegetable Market by Petrus van Schendel, 19th century

-

A Market Scene by Alberto Pasini, late 19th century

-

North African market by Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1923

-

Market in Poltava by Vladimir Egorovich Makovsky, n.d.

-

Fair in Ukraine by Vladimir Makovsky, 1882

See also

References

- ↑ Archaeology Wordsmith, https://archaeologywordsmith.comlookup.php?terms=central+place+theory

- ↑ Britnell, R., "Markets and Fairs in Britain Before 1216," Braudel, F. and Reynold, S., The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th to 18th Century, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1992

- ↑ Koot, G.M.,"Shops and Shopping in Britain: from market stalls to chain stores," University of Dartmouth, 2011, <Online: https://www1.umassd.edu/ir/resources/consumption/shopping.pdf >

- ↑ Casson, M. and Lee, J., "The Origin and Development of Markets: A Business History Perspective," Business History Review, Vol 85, Spring, 2011, pp 9–37. doi:10.1017/S0007680511000018

- ↑ Letters, S., Online Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516 <http://www.history.ac.uk/cmh/gaz/gazweb2.html>: [Introduction]; Davis, J., Medieval Market Morality: Life, Law and Ethics in the English Marketplace, 1200-1500, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 144

- ↑ Building History, http://www.buildinghistory.org/buildings/townwalls.shtml

- ↑ Dyer, C., Everyday Life in Medieval England, London, Hambledon and London, 1994, pp 283–303

- ↑ Davis, J., Medieval Market Morality: Life, Law and Ethics in the English Marketplace, 1200-1500, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp 6-9

- ↑ Braudel, F. and Reynold, S., The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th to 18th Century, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1992

- ↑ Braudel, F. and Reynold, S., The Wheels of Commerce, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1992

- ↑ Honig, E.A., Painting & the Market in Early Modern Antwerp, Yale University Press, 1998, p. 6

- ↑ Clark, P., Small Towns in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 124

- ↑ MacLean, Simon (2003). Kingship and Politics in the Late 9th Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-521-81945-8.

- ↑ "The Medieval City of Esslingen," Neckar Magazine, http://www.neckar-magazin.de/english/cities/esslingen/index.html

- ↑ Fletcher, O., The Making of Western Europe, Vol. II The First Renaissance, 1100-1190 AD, London, John Murray, 1914, pp 41–42

- ↑ Laszlovszky, J., Miklós, Z., Romhányi, B and Szende, K., "The Archaeology of Hungary’s Medieval Towns," Hungary's Archaeology at the Turn of the Millennium, Zsolt, V., ed., Department of Monuments of the Ministry of National Cultural Heritage, 2003, pp 368–372.

- ↑ Ortutay, Gyula. "Magyar néprajzi lexikon". Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. https://www.arcanum.com/en/online-kiadvanyok/Lexikonok-magyar-neprajzi-lexikon-71DCC/m-732AC/mezovaros-7343A/.

- ↑ Somfai, Attila. "KISALFÖLDI ÉS ALFÖLDI MEZŐVÁROSOK KÜLÖNBÖZŐSÉGE, KISVÁROSI ÉRTÉKEK VÉDELME". http://www.sze.hu/ep/arc/irod/SA2002_KisalfAlfkisvaros+SUMMARY/.

- ↑ Holt, R., "Medieval Norway’s urbanizationin a European perspective," in S. Olaffson (ed), Den urbane underskog: Stadsbygge i bondeland – ett forskningsfält med teoretiska och metodiska implikationer, [The Undercooked Urban Landscape: Urban building in the countryside – research, theory and methodological implications], p. 231-246

- ↑ Sturluson, S. , Heimskringla: or, The Lives of the Norse Kings, Courier Corp., 2012 p.567; Larsen,L., History of Norway, Princeton University Press, 2015, p.121

- ↑ Template:Cite Efron

- ↑ "Местечко", an article from the Shorter Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 5, 1990, published online by the Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia

- ↑ Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516, List and Index Society, no. 32, 2003, <Online: http://www.history.ac.uk/cmh/gaz/gazweb2.html>

- ↑ Dyer, C., Everyday Life in Medieval England, London, Hambledon and London, 1994, pp 283-303

- ↑ Borsay, P. and Proudfoot, L., Provincial Towns in Early Modern England and Ireland: Change, Convergence and Divergence, [The British Academy], Oxford University Press (2002), pp 65-66

- ↑ Cate, J.L., "The Church and Market Reform in England During the Reign of Henry III," in J.L. Cate and E.N. Anderson (eds.), Essays in Honor of J.W. Thompson. Chicago, 1938, pp. 27–65

- ↑ Postan, M.M., Rich, E.E. and Miller, E., "Early Markets and Fairs," [Chapter 3] in The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, London, Cambridge University Press, 1965

- ↑ Ottaway, P., Archaeology in British Towns: From the Emperor Claudius to the Black Death, London, Routledge, pp 44-45

- ↑ Chipping Sodbury Town Council, "History", https://www.sodburytowncouncil.gov.uk/history

- ↑ Samantha Letters, Online Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516 <http://www.history.ac.uk/cmh/gaz/gazweb2.html>

- ↑ "Bracton: Thorne Edition: English. Volume 3, Page 198". https://amesfoundation.law.harvard.edu/Bracton/Unframed/English/v3/198.htm#TITLE109.

- ↑ Nicholas, D.M., The Growth of the Medieval City: From Late Antiquity to the Early Fourteenth Century, Oxon, Routledge, 2014, p. 182

- ↑ Casson, M. and Lee, J., "The Origin and Development of Markets: A Business History Perspective," Business History Review, Vol 85, Spring, 2011, p. 28

- ↑ Casson, M. and Lee, J., "The Origin and Development of Markets: A Business History Perspective," Business History Review, Vol 85, Spring, 2011, doi:10.1017/S0007680511000018, p. 27

- ↑ Koot, G.M.,"Shops and Shopping in Britain: from market stalls to chain stores," University of Dartmouth, 2011, <Online: https://www1.umassd.edu/ir/resources/consumption/shopping.pdf >

- ↑ Dyer, C., "Market Towns and the Countryside in Late Medieval England," Canadian Journal of History, Vol. 31, No. 1, 1996

- ↑ Northampton Heritage, Market Squares, http://www.northamptonshireheritage.co.uk/learn/built-heritage-and-the-historic-environment/Pages/market-squares.aspx#expand-NorthamptonMarket

- ↑ "National Market Traders' Federation". Rosiewinterton.co.uk. http://www.rosiewinterton.co.uk/news/westminster/news.aspx?p=102417.

- ↑ "Markets and Fairs". The National Archives. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/research-guides/markets-and-fairs.htm.. Archived 13 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516. University of London Institute of Historical Research. http://www.history.ac.uk/cmh/gaz/gazweb2.html. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Stow, William (1722). "A List of all the Market Towns in England and Wales" (in en). http://www.londonancestor.com/stow/stow-market-all.htm. "SOURCE: 'Remarks on London'"

- ↑ Stow, William (1722) (in en). Remarks on London: Being an Exact Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, Borough of Southwark, and the Suburbs and Liberties Contiguous to Them. T. Norris, and H. Tracy. https://books.google.com/books?id=2dIHAAAAQAAJ.

- ↑ Britnell, R., "Markets and Fairs in Britain Before 1216," [1]

- ↑ "Historic Towns of Scotland". http://www.welcometoscotland.com/articles/historic-towns-of-scotland.

- ↑ Honig, E.A., Painting & the Market in Early Modern Antwerp, Yale University Press, 1998, p.24

- ↑ Honig, E.A., Painting & the Market in Early Modern Antwerp, Yale University Press, 1998, pp 6-10

Bibliography

- A Revolution from Above; The Power State of 16th and 17th Century Scandinavia; Editor: Leon Jesperson; Odense University Press; Denmark; 2000

- The Making of the Common Law, Paul Brand, (Hambledon Press 1992)

- The English Market Town: A Social and Economic History 1750-1914, Jonathan Brown, (The Crowood Press, 1986)

- The English Town, Mark Girouard, (Yale University Press, 1990)

- The Oxford History of Medieval England, (ed.) Nigel Saul, (OUP 1997)

Further reading

- Hogg, Garry, Market Towns of England, Newton Abbot, Devon, David & Charles, 1974. ISBN 0-7153-6798-6

- Chamberlin, E. R., English Market Towns, London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1985. ISBN 0-2977-8528-1

- Dyer, Christopher, "The Consumer and the Market," Chapter 13 in Everyday Life in Medieval England, London, Hambledon & London, 2000 ISBN 1-85285-201-1ISBN 1-85285-112-0

External links

- Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516

- Pictures of England, Historic Market Towns

- Cheshire Market Towns – council maintained guide to Cheshire's Market Towns

Template:Terms for types of administrative territorial entities

|